The development of a socialist conception of art photography in the German Democratic Republic must be seen in the larger context of the formation of a socialist photo-art in Germany. Its beginnings go back to the workers’ photography and its struggle against fascism and militarism. -- Gerhard Henniger, Die Fotografie, 1966

Introduction

John P. Jacob, Boston 1998

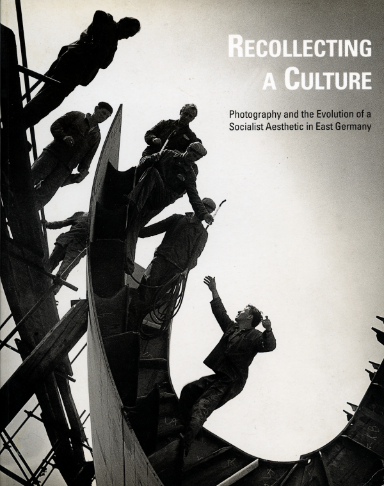

Recollecting a Culture is a study of the political and economic pressures on the visual arts of the German Democratic Republic (GDR). It draws from the Fotokino Archive, comprised of approximately 14,000 prints and several thousand negatives, which was accessioned by the Staatliche Galerie Moritzburg Halle from the publisher V.E.B. Knapp, Leipzig, in 1989. Knapp began publication of the monthly periodical Die Fotografie in 1860. After the Second World War, along with all other media industries in the Soviet sector, Knapp fell under the control of the East German state. Publication of Die Fotografie was resumed in 1947. In 1964, the publishing house was moved to the nearby city of Halle (Saale) and its name changed to the Fotokinoverlag. Of the two periodicals published by the Fotokinoverlag between 1947 and 1991, Fotokino represented the interests of East German amateurs and photographic societies, while Die Fotografie presented professional and art photography from East Germany and abroad. In 1991, following the collapse of the East German economic and political structure, the Fotokinoverlag was closed.

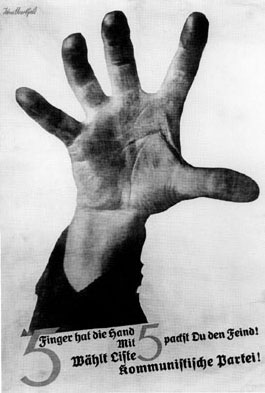

As an instrument of East German socialism, Die Fotografie proposed a provocative revision to the history of photography. “The development of a socialist conception of art photography in the German Democratic Republic…” Gerhard Henniger wrote in 1966, “must be seen in the larger context of the formation of a socialist photo-art in Germany. Its beginnings go back to the workers’ photography and its struggle against fascism and militarism… Only in this way can one adequately judge the national and historical significance of our daily activities.” (DF 1/66, p. 8) Thus, in contrast to Western histories built upon a foundation of works by modernist and early-modernist masters, the history of East German photography was built from a body of images by amateurs and artists, largely unknown outside Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, whose photographs depicted the world from the class perspective of the worker. The works published in Die Fotografie and archived by the Fotokinoverlag were valued for their cultural and political resonance, and for their affirmation of the “humanistic impulse” as photography’s most significant contribution to art.

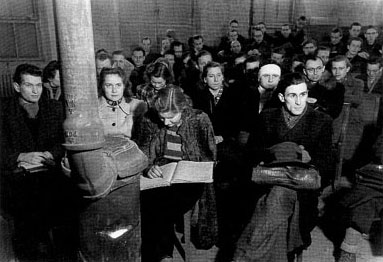

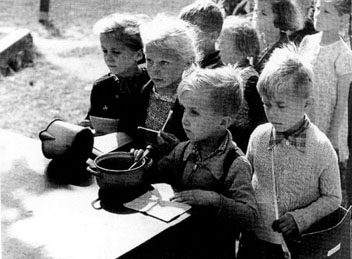

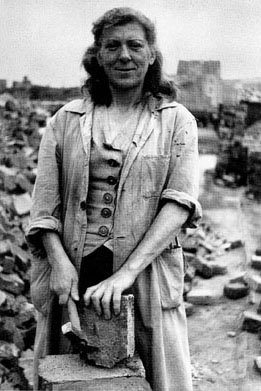

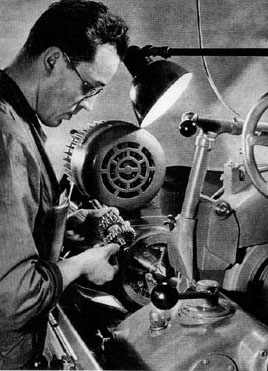

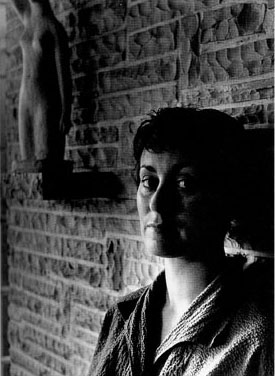

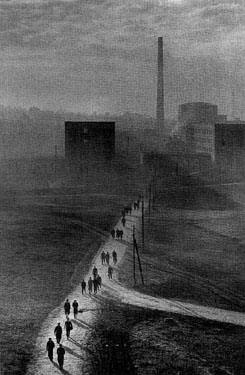

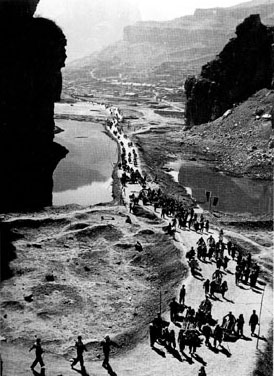

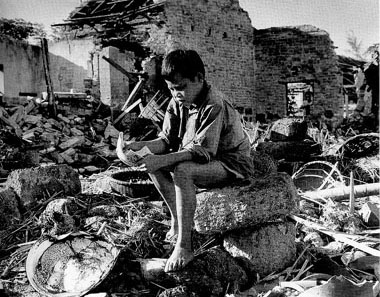

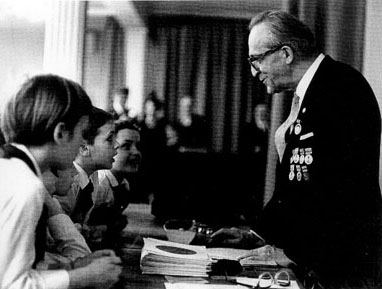

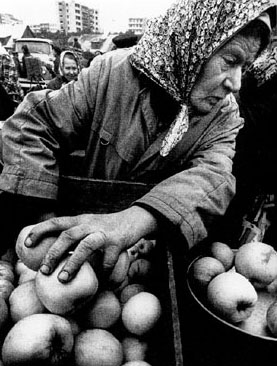

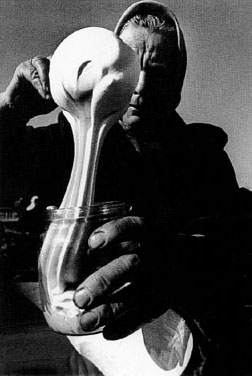

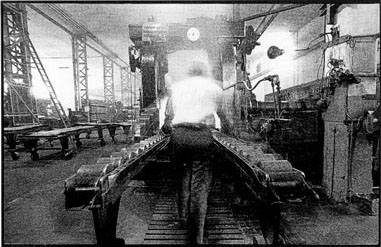

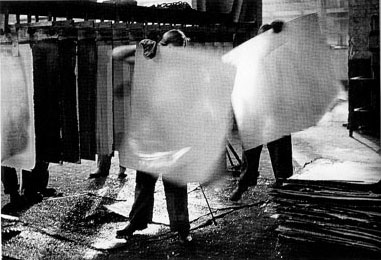

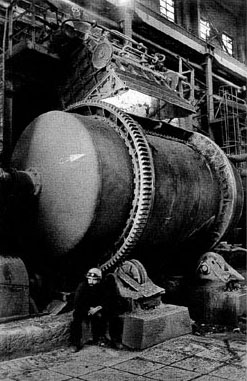

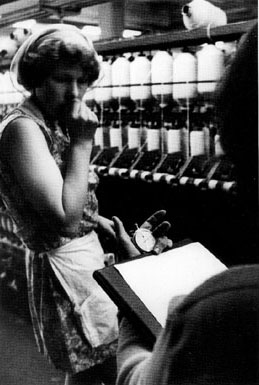

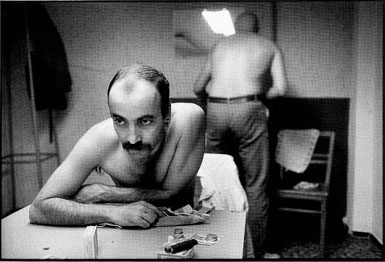

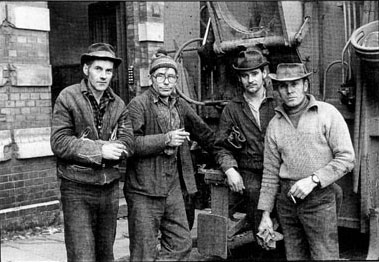

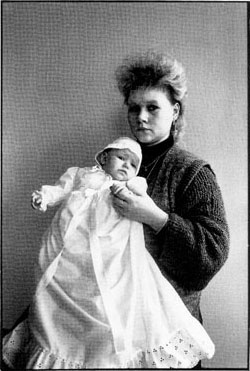

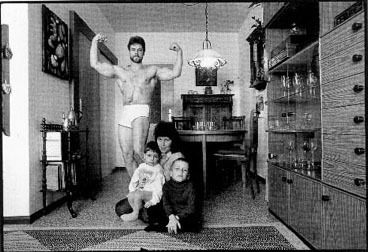

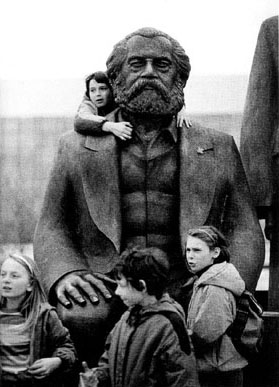

The first phase of East German photography, beginning in the late 1940s and institutionalized with the establishment of the Central Commission for Photography (ZKF) in 1960, represents a deliberate severance from western traditions. The first generation of East German photographers, including many who had participated in the worker photography movement of the 1930s such as Walter Ballhause and Eugen Heilig, focused on documenting the construction of socialism in Germany and developing an iconography of the peasant and workers’ state. An heroic image of the worker was articulated by artists such as Paul Damm and Käte Basarke, and a distinct East German style emerged characterized by realism in form and narrative. Of particular importance were photographic depictions of key socialist “types” and moments, carefully posed to enhance their drama of purpose and clarity of meaning. “Socialist realism represents reality in its revolutionary development, in its most progressive appearances. From these appearances, it then chooses the most basic, typical, and characteristic,” Professor W.P. Jefanow, Secretary of the Union of Soviet Fine Artists, declared in an interview in Die Fotografie. “The main task of the artist is to render man and his life in all its variety.” (DF 12/53, p. 331)

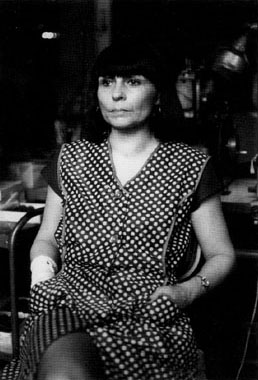

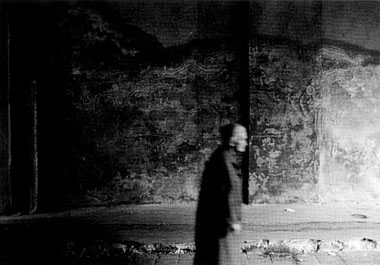

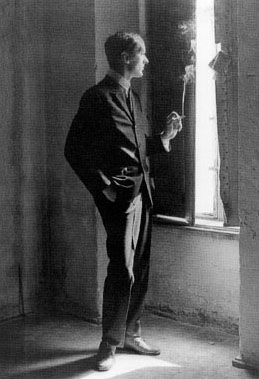

Many East German photographers banded together in professional support groups in the late 1950s, including non-conformists like the Leipzig based Action Fotografie. In spite of the ZKF’s call to photographers “to serve to render our present and our life even more beautiful,” (DF 8/60, p. 292) the non-conformists insisted that life and truth were more complicated than the “smooth, happy pictures” of socialist realism (DF 11/56, p. 304). The detachment that these artists cultivated in the early years of the GDR undermined the visual uniformity of socialist culture in the media, and may have contributed to the editorial takeover of Die Fotografie by the ZKF in 1960. Throughout the 1960s and ’70s, both as independent artists and as faculty at the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst in Leipzig, they quietly spread their dissatisfaction with socialist aesthetics to their students, building a foundation for the more directly confrontational images of later generations of photographers. While seeming to adhere to the Soviet standard of humanistic art, work from this period by artists such as Arno Fischer and Evelyn Richter is characterized by a studied ambivalence toward its subjects. The presence of non-conformists in the seemingly fixed field of photography, and their move toward a more objective vision, resulted in an ideological divide among photographers that grew increasingly profound with the passage of time.

The Fotokinoverlag’s massive archiving of images began during the 1960s, and functioned primarily to valorize and authenticate the ideological mandate of the ZKF. The archive was the heart of East Germany’s evolving socialist aesthetic, its history as well as its future, and an artist’s relationship to it defined his or her position in relation to socialist culture. The archive also provided the state with an apparatus for observation of an artist’s production over an extended period of time. By assuming the right to re-present images under changing circumstances (as Richard Peter, Sr.’s photographs of the aftermath of the Dresden firestorm were differently presented in various historical and artistic contexts, for example), Die Fotografie’s editors also assumed the power to alter the meaning of those images over time. Thus, the Fotokino Archive was not merely an accumulation of social knowledge about East Germany, but a powerful engine of socialist propaganda and control.

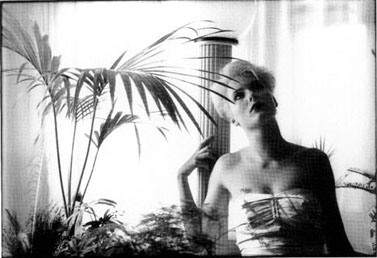

The ZKF exercised its authority during the 1960s and ’70s through its direction of Die Fotografie and the Fotokino Archive. Most photographers, wishing to stay employed in their chosen field, complied with Die Fotografie’s aesthetic agenda. Many, however, found ways to work around it. A photographer might present a critique of a foreign country, showing poverty in the USA or strikes in West Germany for example, but not of comparable problems in East German society. East German artists were also held up to a higher standard than their foreign colleagues. Chemical pollution and social isolation were safe subjects for Czech photographers as early as 1973. Nude photography by East German artists was characterized by its implicit statement of physical health, while nudes from Poland were technically experimental and frequently erotic. The policy of different standards for different artists contributed to the instability of socialist aesthetics, and to the growing division between photographers who served the goals of the state and those who sought a higher purpose for their art.

The fine line that some East German photographers straddled between conformity and personal self-expression was made possible by the relaxation of Soviet authority following the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953. During the ensuing thaw, the constitution of the GDR was revised by the state legislature to reflect the evolving identity of the growing nation. Socialist realism was revised to reflect both the growing independence of East German art from the Soviet mold and the awakening of East German artists to their own cultural history. Having apparently outgrown its close identification with Stalinist rigidity, East German socialist realism came to be theorized from two opposing points of view. One side argued that change itself was the fundamental characteristic of socialist realism, and that this transformative quality was the key to its endurance and social significance. The other side concluded that socialist realism lacked theoretical coherence. Socialist realism, they declared, had been degraded into a slogan or sign used by proponents of widely opposing ideologies but was meaningless in and of itself. For these artists, the absence of a theoretical substructure revealed the superficiality of socialist realism, and suggested the eventual collapse of the authority of the state in cultural affairs.

The fine line that some East German photographers straddled between conformity and personal self-expression was made possible by the relaxation of Soviet authority following the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953. During the ensuing thaw, the constitution of the GDR was revised by the state legislature to reflect the evolving identity of the growing nation. Socialist realism was revised to reflect both the growing independence of East German art from the Soviet mold and the awakening of East German artists to their own cultural history. Having apparently outgrown its close identification with Stalinist rigidity, East German socialist realism came to be theorized from two opposing points of view. One side argued that change itself was the fundamental characteristic of socialist realism, and that this transformative quality was the key to its endurance and social significance. The other side concluded that socialist realism lacked theoretical coherence. Socialist realism, they declared, had been degraded into a slogan or sign used by proponents of widely opposing ideologies but was meaningless in and of itself. For these artists, the absence of a theoretical substructure revealed the superficiality of socialist realism, and suggested the eventual collapse of the authority of the state in cultural affairs.

That several of East Germany’s best known photographers were never represented in Die Fotografie is the result of a political ban on their work. Artists who produced images too distant from the socialist definition of photography (Thomas Florscheutz, for example, who in 1987 won European Photography’s First Prize for Young Photographers and exhibited in West Germany, France, and the USA, but was unpublished in East Germany and exhibited there only in private galleries) were prohibited from its pages, and thus forced to find refuge for their work in underground galleries and foreign journals. Others were omitted from Recollecting a Culture when it was apparent that Die Fotografie’s editors had selected the weakest work of an otherwise powerful artist (Gundula Schulze, for example, whose controversial portraits and nudes drew thousands of visitors from throughout Germany to the tiny White Elephant Gallery in East Berlin in the mid 1980s, but who was represented in Die Fotografie by a series of academic landscapes).

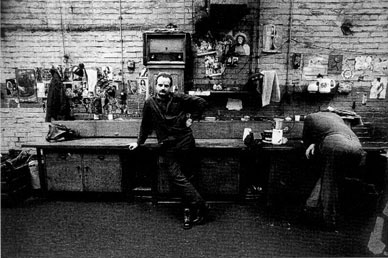

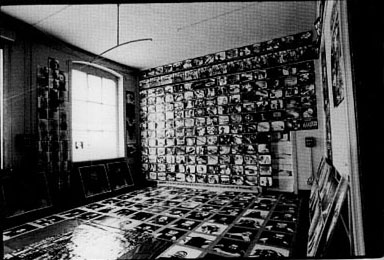

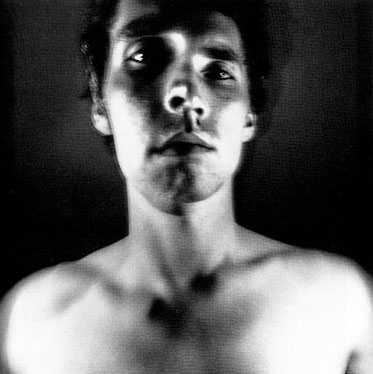

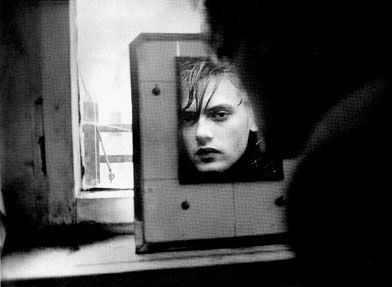

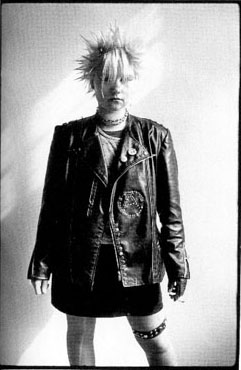

The wholly unexpected publication of Peter Oehlmann’s photo-installation “Selbstbefragung” in 1983 spoke eloquently for the many artists who were prohibited from Die Fotografie. The installation, composed of dozens of nude and angst-filled self-portraits of the artist, on the walls and floor of the gallery, plus a wall of images photographed from television and objects hanging from strings, had the appearance of a “private” or illegal exhibition. Its publication was unprecedented, and acknowledged the existence of a community of artists that had, until that moment, worked in utter obscurity outside the system of state support. Nothing that followed it was ever quite as shocking. Nevertheless, publication of Oehlmann’s work appears to have opened the floodgates for the presentation of works by a new generation of young artists who flatly rejected socialist aesthetics, and focused instead on the formerly hidden details of East German life. Images of sexual ambiguity and forthright eroticism, punk culture, apathy in the workplace and despair at home, as well as photographs that mocked state prohibitions on photography, grew increasingly common in the late 1980s, and drew large audiences to the exhibitions in which they were presented. The last generation of East German photographers struggled uncompromisingly to reinvest the image-making process with truth-value. If their work proved unpublishable in East Germany, rather than allowing the state to reduce them to silence, as had many of their predecessors, they sent it elsewhere and suffered the consequences.

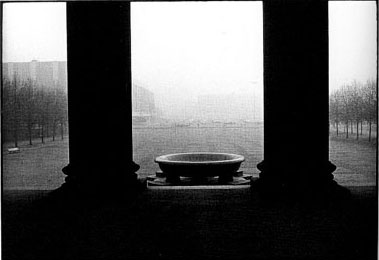

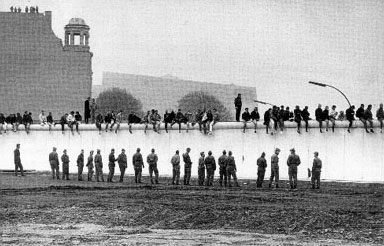

The photography of everyday life, showing the gradual collapse of personal, social, and political stability in East Germany, is the true subject of this book and exhibition. Nowhere is this collapse more evident than in the ever-changing editorial mandates, the diatribes against bourgeois photography, the infrequent bold excursions into uncharted ground, and the progressively critical images presented in Die Fotografie. And nowhere is the failure of its socialist aesthetic more evident than in Die Fotografie’s editorial refusal to acknowledge the fall of East Germany in 1989. Images of the dismantling of the Berlin Wall and the demonstrations that preceded it do not appear in the periodical until 1990, a full year or more after they occurred. In its failure to recognize this most spectacular event through the photography of everyday life, Die Fotografie lost its opportunity to stay relevant to East Germans living and working in a fundamentally altered world. The final issue of Die Fotografie was printed in March 1991.

A small sampling of articles, most written during the 1960s, is presented here more or less in their original format, as seen in the pages of Die Fotografie. All of these articles were written by representatives of the ZKF, and all were selected for the clarity of the imperatives they describe. However, it should be noted that in addition to such politically oriented texts Die Fotografie regularly published one-person portfolios, group portfolios (frequently by worker’s brigades, but more often than not describing a particular theme or issue), instructional articles on scientific and “leisure” photography (animals, nature, travel, etc.), articles by curators, letters to the editor (including a popular forum for readers to respond to images), and much more.

Die Fotografie was read internationally, in communist as well as capitalist nations. Moreover, although it focused on work that underwrote its aesthetic agenda, Die Fotografie regularly presented images by historical and contemporary photographers from throughout the world. The photographs presented in Recollecting a Culture, however, are limited to artists from East and West Germany, the USSR and its European satellites, China, and communist Southeast Asia. My hope was that by narrowing its scope, Recollecting a Culture would be made to illustrate that, within the context of a divided nation and an evolving socialist aesthetic, East German photography grew from a strain of Soviet socialist realism to a distinct critical practice, and that Die Fotografie played a crucial, if not always positive, role in that development.

To American eyes, the methods and subjects of East German photography may appear formulaic and cliched. Writing on behalf of the ZKF, in 1960 Gerhard Henniger listed the themes most worthy of pursuit by East German photographers as “[one’s] own practice within production, his life in the brigade, within the family, his holidays, his recreation, his sports […] socialist naming and marriages, brigade evenings and cooperative meetings.” (DF-8/60, p. 292) Yet what we regard as banalities, images of the ordinary, are captured here with complete conviction. In fact, what distinguishes so much of the work presented in Die Fotografie is its simultaneous rejection of style and embrace of issues, such as health, work, youth and age, and leisure, all pictured though the lens of cultural politics. While acknowledging the humanism of The Family of Man and the work of the Magnum cooperative, the theorists of socialist aesthetics rejected the decisive moment as a mere formalist novelty. The stylistic elements of “critical realism,” as such favored Western photography was called, could not disguise its basis in class values. “Despite all critique of bourgeois society, the bourgeois class point of view is not abandoned,” Dr. F. Herneck wrote in 1960. (DF 8/60, p. 308) Socialist realism, by contrast, with its roots in the workers struggle and its ideals in the collective vision, represented a higher artistic achievement.

These ideas take some getting used to, and are easy to dismiss with post-1989 hindsight. That Die Fotografie was an organ of the state, and its advocacy of socialist realism a tool of East German propaganda, is self-evident. But to state, as Karl Gernot Kuehn does in Caught: the Art of Photography in the German Democratic Republic, that the ZKF’s editorial control over Die Fotografie represented “the certain end of the magazine as an occasional platform for subtle defiance” (Kuehn, p. 57), is ahistorical, untrue, and unjust to the editors, writers, and photographers whose work for the periodical did take risks. Moreover, searching for evidence of defiance is an inappropriate method for judging the impact of Die Fotografie on East German culture. Rather, the ability to work around the editorial mandate of the ZKF, undermining the theorists of socialist aesthetics by surpassing their demand for realism, is the key to much East German photography. In the end, the most powerful defiance was expressed by artists who adhered to Die Fotografie’s most fundamental demand: that they “represent reality in its revolutionary development… render[ing] man and his life in all its variety.” (DF 12/53, p. 331)

Recollecting a Culture is the culmination of nearly two decades of work with photographers from the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. During that time, I have worked almost exclusively with artists operating at the fringe of so-called “official” socialist culture. From the start, the idea of official versus unofficial cultures fit neatly into my conception of how contemporary art must exist in relation to socialism, and had to be shot down regularly by artists, editors, curators, and other administrators whose work, when properly presented and understood, told a much more complicated story. In fact, cultural workers in Eastern Europe did not occupy a zone of such black and white clarity as the terms official and unofficial (dissident vs. compliant) describe. Rather, they worked within a context of utter instability. In East Germany especially, this instability was sustained by an extraordinary level of bureaucracy, which transformed the terror of observation and control into banalities of everyday life. By the late 1980s, East Germany had become the society that Guy Debord described when he wrote that “totalitarian bureaucratic society lives in a perpetual present in which everything that has happened earlier exists for it solely as a space accessible to its police.” (Debord 1967, p. 75)

In no other circumstance have I ever seen the demand for truth so completely at odds with its result as in the art of East Germany. Recognizing this inherent contradiction, in the 1980s, East German photographers joined with artists, journalists, writers, and others throughout Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union seeking to redefine their cultures in their own terms. Whether traditional or experimental in approach, the goals of the last generation of East German artists were consistent with the goals of the first: to truthfully and realistically portray the socialist transformation of the German Democratic Republic. That they accomplished their goal, and in so doing contributed significantly to the transformation of late 20th century Europe, is a testament to the continuing power of photography to inform, to challenge, and to inspire.

Recollecting a Culture: Photography and the Evolution of a Socialist Aesthetic in East Germany

An exhibition of the Photographic Resource Center at Boston University, January 8 – February 19, 1999

Introduction

John P. Jacob

Acknowledgements

John P. Jacob

Photographs

Die Fotografie – An Interview with the Editor

T.O. Immisch and Gerhard Ihrke

Articles

Author Uncredited

Industry, its people – and the photographer. Die Fotografie 4/1948

Wolfgang Hütt

Photography of the Proletariat: A note on files and documents concerning the history of worker photography. Die Fotografie 8/1960

Gerhard Henninger

Path and Goal of Amateur Photography in the GDR. Die Fotografie 8/1960

Dr. F. Herneck

Concerning the Question of Socialist Realism in Photography. Die Fotografie 8/1960

Gerhard Henninger

Problems of Socialist Realist Photographic Art. Die Fotografie 11/1960

Rudolf Wedler

Photography Prohibitions (or: unlawful photography). Die Fotografie 3/1962

Gerhard Henninger

Concerning the significance of the traditions of German Workers’ Photography. Die Fotografie 1/1966

Walter Ulbricht

Words on Photography. Die Fotografie 8/1968

Booklists

Books of the Fotokinoverlag with/about GDR-Photography

Other important books about GDR-Photography (Selection)

Exhibition Rental

Postscript

John P. Jacob

Acknowledgements

In 1987, during a visit to East Berlin, my friend Karla Sachse gave me a book, one of the final publications pf the Fotokinoverlag, titled Fotografie in der DDR. At the time, it seemed to me an abysmal collection of photographic cliches. Yet many of those photographs appear in Recollecting a Culture. What has changed between then and now?

Almost everything. But the photographs have remained the same: traces of a world so utterly foreign that I might never have been drawn into it without the encouragement of many who lived there, and the support of others who did not. Rimma and Valeriy Gerlovin gave me both the courage and the contacts that I needed to start with. Andrea and Tibor Várnagy, Maria and Milan Knízák, Anna Bohdziewicz and Janusz Lipinski, Theo and Maria Immisch, and Karla Sachse and Joseph Huber, provided care and conversation that has deeply inspired and changed me over the years. I am indebted to many friends and colleagues for sharing their homes and the fruits of their learning, including Tony Dufek, Klaus Elle, Monika Faber, Thomas Florscheutz, Steffan and Martina Giersch, Marek Grygiel, Marek Gardulski, Volker Hamann, István Halas, Stephen and Brigitte Jacob, Lech Lachowicz, Andreas Leupold, Matthias Leupold, Lugosi Lugo and Aljona Frankl, Vaclav Macek, Thomas Ruller, Piotr Rypson, Tatiana Salzirn, Jurgen Schöberl, Aleksey Shulgin, and Zsuzsi Ujj.

Between 1986 and 1991, my work in Central Europe and Russia was made possible by a series of generous travel grants from the Soros Foundation, New York. My early work on East German Photography, and a first version of the essay that accompanies this catalogue, were presented at the College Art Association national conference in 1993, in a panel moderated by Vicki Goldberg. More recently work on Recollecting a Culture was supported by a generous Creation and Presentation grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), and by funding from the Goethe Institute, Boston.

The exhibition and accompanying publication of Recollecting a Culture were made possible through the cooperation of the Staatliche Galerie Moritzburg Halle. I am especially grateful to Dr. Peter Romanus, Director, and Theo Immisch, Curator of Photographic Collections, for their commitment to this project. Thanks are also due to the staff of the Photography Collection for their contributions. In particular, Gerhard Ihrke, Curator of the Fotokino Archive, patiently fulfilled all of my requests for material and information. I’m also grateful to Klaus E. Göltz for the design of this book, and to Christine Mehring for the translations of the texts that accompany it.

Recollecting a Culture is an exhibition of the Photographic Resource Center (PRC) at Boston University, which receives support for its programs from the NEA, the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the generosity of its board of directors and its members, and other private and public donors. Over the last three years, PRC staff members Sara Rosenfeld Dassel and Lizzie Fischbein, and former staff members Erica Kessel and Robert Seydel, have contributed significantly to the development of Recollecting a Culture. I am grateful to them, and to all the individuals and institutions who have supported this project over the nearly ten year period that it has evolved.

My greatest debt, for all that I have done and more than words can say, is to my family, Deborah Chapman and Acadia Jacob. Thank you.

John P. Jacob

Photographic Resource Center at Boston University

© 1989 by Photographic Resource Center at Boston University, authors and photographers

Recollecting a Culture: Photography and the Evolution of a Socialist Aesthetic in East Germany

An exhibition of the Photographic Resource Center at Boston University, January 8 – February 19, 1999

Introduction

John P. Jacob

Acknowledgements

John P. Jacob

Photographs

Die Fotografie – An Interview with the Editor

T.O. Immisch and Gerhard Ihrke

Articles

Author Uncredited

Industry, its people – and the photographer. Die Fotografie 4/1948

Wolfgang Hütt

Photography of the Proletariat: A note on files and documents concerning the history of worker photography. Die Fotografie 8/1960

Gerhard Henninger

Path and Goal of Amateur Photography in the GDR. Die Fotografie 8/1960

Dr. F. Herneck

Concerning the Question of Socialist Realism in Photography. Die Fotografie 8/1960

Gerhard Henninger

Problems of Socialist Realist Photographic Art. Die Fotografie 11/1960

Rudolf Wedler

Photography Prohibitions (or: unlawful photography). Die Fotografie 3/1962

Gerhard Henninger

Concerning the significance of the traditions of German Workers’ Photography. Die Fotografie 1/1966

Walter Ulbricht

Words on Photography. Die Fotografie 8/1968

Booklists

Books of the Fotokinoverlag with/about GDR-Photography

Other important books about GDR-Photography (Selection)

Exhibition Rental

Postscript

John P. Jacob

Photographs

Recollecting a Culture: Photography and the Evolution of a Socialist Aesthetic in East Germany

An exhibition of the Photographic Resource Center at Boston University, January 8 – February 19, 1999

Photographers:

Carla Arnold

Walter Ballhause

Tina Bara

Käte Basarke

Sibylle Bergemann

Volkmar Billeb

Helmut Broschk

Paul Damm

Walter Dreizner

Jochen Ehmke

Christiane Eisler

Arno Fischer

Christina Glanz

Konstanze Göbel

Kurt H. Hartmann

John Heartfield

Eugen Heilig

Walter Heilig

Albert Hennig

Herbert Hensky

Matthias Hoch

Erich Höhne

Frantisek Hubásek (Czechoslovakia)

Joseph W. Huber

Max Ittenbach

Hanna Jähnig

Eberhard Klöppel

Peter Koard

Rudolf Koch

Viktor Kolar (Czechoslovakia)

Hans-Wulf Kunze

Burkhardt Lange

Bernd Lasdin

Peter Leske

Matthias Leupold

Joachim Liebe

Alexandras Macijauskas (Lithuania)

Ute Mahler

Karl Heinz Mai

Wolfgang A. Mallwitz

Sven Marquardt

Erich Meinhold

Florian Merkel

Heinz Müller

Dr. Gerhard Murza

Heinz Nitschmann

Peter Oehlmann

Helga Paris

Robert Paris

Richard Peter sr.

Richard Peter jr.

Hans Joachim Reiter

Evelyn Richter

Klaus Rose

Günter Rossenbach

Thomas Sandberg

Boris Saweljew (Russia)

Frank Schenke

Erasmus Schröter

Werner Schulze

Erich Schutt

Bernd-Horst Sefzik

Petr Sikula (Czechoslovakia)

Valentin Sobolew (Russia)

Gerhard Stegelin

Detlev Steinberg

Uwe Steinberg

Helfried Strauß

Horst Sturm

Antanas Sutkus (Lithuania)

Nina Swiridowa (Russia)

Wei Teh-chung (China)

Ernö Vadas (Hungary)

Ralf-Rainer Wasse

Karin Wieckhorst

Fritz Winkler

Katja Worch

Die Fotografie – An Interview with the Magazine’s Editor

T.O. Immisch, curator of the collection of photographs at the Staatliche Galerie Moritzburg Halle, which has housed the picture collection of the former Fotokino publishing house since 1992, asked the questions. Answers were given by Gerhard Ihrke, photographer, author, and editor, who from 1964 till 1991 was the editor of the publishing house’s two magazines, Die Fotografie and Fotokinomagazin. Now he is caretaker of the Fotokino collection at the museum.

How was this magazine re-established at Halle’s Knapp publishing company after the war?

By doing so, the Wilhelm Knapp publishing company continued a tradition. More than one hundred years before, in 1839, the first instruction on daguerreotyping in German had appeared in Halle. The Knapp publishing company published various photographic magazines, and so it was only logical that they also tackled the publication of a photo magazine after the war again, which happened under very difficult circumstances. The first issue of Die Fotografie appeared in July 1947 in the then Soviet-occupied zone. This issue’s subtitle named the previous seven different magazines, which referred to the various publications of pre-war times. It is therefore no wonder that the magazine was of nearly all-German character, as photographs and articles by authors from all over Germany were published in it. This did not change until the end of the 1950s. After 1961, publication of authors from the Federal Republic became a mere exception. However, this was mainly due to the fact that the publishing company and the editorial staff were lacking the foreign currency required to pay the fees. In 1952, the Wilhelm Knapp publishing company was transformed into a state-owned company. This firm name led to complications in the export of the magazine, and even more so with the books, into the Federal Republic; and therefore, they decided in 1957 to rename the »VEB Wilhelm-Knapp-Verlag« publishing company to »VEB Fotokino-Verlag«. Now, export to West Germany was possible again. It should be mentioned, however, that only a few issues of the magazine were delivered to the Federal Republic, whereas things were different with the technical photographic books, which were much sought-after even in the Federal Republic.

How did the magazine become an extension of the Central Commission of the Cultural Association of the German Democratic Republic?

The Central Photography Commission (ZKF) of the Cultural Association of the GDR was an umbrella organization for the photographic work in the GDR. It coordinated the photographic work in the country, organized photographic exhibitions and supported the social recognition of photography, which then – unlike in the USA – still represented a peripheral phenomenon in society, culture and art. Naturally, a magazine was needed for that, and therefore they ended up combining the Central Commission with the »Fotokinoverlag« publishing company. The Central Photography Commission became responsible for the editing of the Die Fotografie magazine.

What goals did the ZKF pursue with the magazine and how did they influence its contents and layout?

It has already been suggested what the ZKF was interested in, what has to be emphasized, however, is a statement that appeared in the December 1957 issue of the magazine and that actually expresses everything with regard of the aims being pursued at that time. It reads: »Photography is to be led out of a state of unconscious Weltanschauung and political neutrality in order to have it, being an activity in accordance with party thought, consciously embrace the building of GDR socialism.« An advisory committee consisting of leading members of the ZKF presidency was charged with monitoring the editorial staff. This advisory committee was informed of everything that was to be published, and later they evaluated the published magazines. Some articles and photo publications were frequently criticized, and this went on until the end of the 1960s.

What were the effects of the politico-cultural »breaks« – for example in 1965, after the 11th Plenum* or in 1971, after the change from Ulbricht to Honecker?

I guess that after 1971 a certain tolerance emerged or started to become apparent. This had an effect also on the work of the editorial staff, as in some respects they could tackle problems of photography, regarding contents, in a more liberal way and publish more differentiated photographic conceptions. What I mean is, it was no longer so much the point to publish representations that were to be classified as »socialist realism« as it is called. Now, the advisory committee was more open-minded about many subjective photographic ideas.

Were there times of greater or lesser independence of the editorial staff?

In spite of the supervision of the ZKF, the editors were comparatively independent. They chose the subject matter, determined the make-up of the magazine, and emphasized the main points regarding content. After the issues were published, the advisory committee discussed the magazine. This was normally done every six months. In a sense, the editorial staff did work independently. There was a good cooperative relationship between the advisory committee of the ZKF and the editors. Naturally, the projects and plans of the ZKF and the later Photographic Society (GfF) were supported and promoted by publications. For example, editors were represented in juries of photo shows, they were involved in the development of large-scale exhibitions, and so, at an early stage got some sort of an idea of the pictures to be selected for the magazine and of potential themes. It was important that the editorial staff be informed early because they had to prepare each issue four months in advance of printing. Can you imagine, how they wished to be topical?

Was it a problem to meet the double demand of making a magazine for both professionals and amateurs?

Yes and no. As the ZKF and the later GfF were organizations that felt bound to both professional and amateur photography, as editorial staff, we had to take into consideration works from these fields as well. In many cases, use was made of articles on exhibitions, exhibition evaluations, reviews, contributions on renowned photographers, well-working and efficient photo groups and clubs, and so it actually wasn’t too difficult to bring these works from different fields together. Of course, discontinuities in quality happened. Discontinuities also happened because of one characteristic printing feature: First forme and second forme printing reproduction of color pictures was possible to a very limited extent only. Therefore, the position of those color pages often determined the length of contributions. As color photography at that time couldn’t keep pace with black-and-white photography, again, discontinuities were the result. Looking upon them today, absolutely embarrassing ones, in some cases.

For years, the »Fotografie« magazine had been printed in letterpress printing. Why did the publishing company change to intaglio printing in the 80s?

The magazine was among the few that were now and then granted an increase in circulation in spite of the paper shortage existing in the GDR. The publishing company couldn’t just simply increase the circulation off its own bat, but it was the state authorities who decided on a larger paper allotment and with that on a higher circulation. In the 1980s, 50,000 issues of Die Fotografie were printed (and sold) in good quality. Further increases in circulation, however, wouldn’t have been anymore possible in letterpress printing, technically. From No 1/1981 the magazine appeared in intaglio printing. To that the editorial staff had pinned high hopes, as intaglio printing, after all, is a fantastic technique for reproducing photographs in all their subtle gradations. Unfortunately, the printers didn’t always succeed in meeting those expectations. That had mainly something to do with the paper quality, but nevertheless, intaglio printing was very well received by the community of photographers in this country.

Why was publication of the magazine stopped and the publishing company closed down?

At the time when the Wall came down, in 1989, the magazine had a circulation of approximately 75,000. Now, however, that the press publications of the Federal Republic were glutting the local market and people had to make up for lost time, it is quite obvious that the circulation of all of the »Eastern« magazines crashed. The newsstands were flooded with the colorful pictures of the magazines from the Federal Republic. The publications of the »East« were lying around somewhere at the back and were hardly in demand anymore. It took some time until this leveled off and the demand of those concerned was satisfied. They noticed that the others were not different from anybody else. In the middle of 1990 the circulation of Die Fotografie leveled out at 16,000 sold issues, which just absolutely corresponded to the demand in the ancient GDR. It is therefore no wonder, that the publishing company gradually got into financial difficulties and the printers refused to continue working on the magazine. So the April 1991 issue had to be withdrawn from the printing house. The March 1991 issue was the last issue of Die Fotografie magazine. It was only after the magazine had disappeared from the market that they noticed, and this was the case with other local press publications as well, that now something was missing. Revival, however, was not possible. The publishing company was taken over by the trust company and finally sold. The new owner was not interested in the »Fotokino« literature. In June 1992, a 150 year old publishing tradition came to an end.

How do you judge today the importance, role, and function of the magazine – what did it achieve and what did it not achieve?

I’m afraid it’s not easy for me to answer this, naturally, because I had been working for more than 25 years with that editorial staff. Over all those years we really tried hard to deliver a very true reflection of the development of photography in the GDR. We tried not to miss any of its facets and to take any sphere into consideration. I guess, on closer examination, those years’ issues deliver a vivid reflection of photography in the GDR. By presenting exemplary works of renowned photographers from at home and abroad, especially from the socialist countries, reporting on their working methods and acknowledging their work, we were able to present examples which did have an effect. In the wider sense, Die Fotografie was a kind of picture book, and this was something that did partly make up its popularity, as otherwise they wouldn’t have been able to sell a circulation of that size at the newsstands in our little country.

Do you see any magazine in the German-speaking world at present, which is similar or comes close to »Fotografie« as far as standard and program is concerned?

This question isn’t so easy for me to answer either. People who live (or better used to live) in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones. I’m afraid, a magazine like Die Fotografie with its message and design in those days wouldn’t be possible anymore today. Our unspoken shining example was the Swiss magazine Camera. Due to tightened conditions, it had already disappeared from the market in 1981. As I see it, there isn’t anything comparable anymore among the German-speaking magazines.

* The 11th Plenum of the Central Commity of the Socialist Unity Party, with which a very restrictive phase in the East German cultural policy began.

Recollecting a Culture: Photography and the Evolution of a Socialist Aesthetic in East Germany

An exhibition of the Photographic Resource Center at Boston University, January 8 – February 19, 1999

Introduction

John P. Jacob

Acknowledgements

John P. Jacob

Photographs

Die Fotografie – An Interview with the Editor

T.O. Immisch and Gerhard Ihrke

Articles

Author Uncredited

Industry, its people – and the photographer. Die Fotografie 4/1948

Wolfgang Hütt

Photography of the Proletariat: A note on files and documents concerning the history of worker photography. Die Fotografie 8/1960

Gerhard Henninger

Path and Goal of Amateur Photography in the GDR. Die Fotografie 8/1960

Dr. F. Herneck

Concerning the Question of Socialist Realism in Photography. Die Fotografie 8/1960

Gerhard Henninger

Problems of Socialist Realist Photographic Art. Die Fotografie 11/1960

Rudolf Wedler

Photography Prohibitions (or: unlawful photography). Die Fotografie 3/1962

Gerhard Henninger

Concerning the significance of the traditions of German Workers’ Photography. Die Fotografie 1/1966

Walter Ulbricht

Words on Photography. Die Fotografie 8/1968

Booklists

Books of the Fotokinoverlag with/about GDR-Photography

Other important books about GDR-Photography (Selection)

Exhibition Rental

Postscript

John P. Jacob

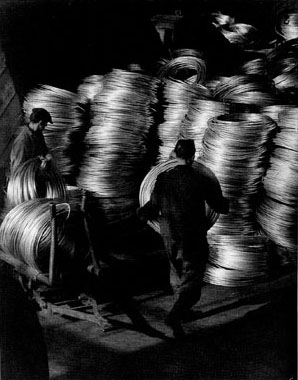

Industry, its people – and the photographer

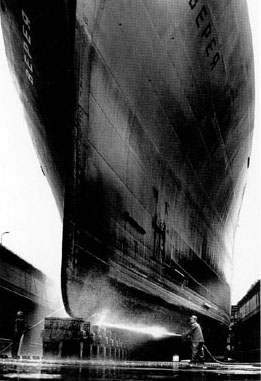

Author Uncredited, Die Fotografie 4/1948

When hearing the term »industrial photography,« the layman frequently has a very specific understanding of it, an understanding which only incompletely and one-sidedly gets to the essential core of this important branch of photography. That is: He mainly sees steaming chimneys, giant workshops, conveyor systems, or, at most perhaps endless and loaded freight trains. In his mind (and he never thought about it), industrial photography is nothing but constantly new versions of the representation of these industrial symbols.

In addition, he usually allows these images to speak to him in some sort of romantic way, and not as merciless objective documents of civilization. Last but not least, this is the case because the photographs of these industrial symbols, which were meant for general viewing contexts (and hence for a large audience), had a more or less noticeable, romantic aura. Photographic exhibitions, cultural magazines, picture calendars, and photo-yearbooks showed this clearly – always under the condition that exceptions only confirm the rule.

Purely objective representations were reserved for specialists who had a specific interest and were part of their context.

Back to the layman and his very incomplete understanding of industrial photography. What does he know of the exceptional role that photography plays in and for the industry today? Yes, one is often confronted with the opinion that the industrial photographer is second-rate. He is so because he takes photographs only of lifeless objects. Furthermore, one often searches in vain for essential traits of the beautiful in these objects. By the least, these are undoubtedly objects whose national-economic usefulness has priority over any aesthetic considerations. From such a (one-sided) viewpoint, the practice of industrial photographers could appear profane in comparison to the creations of a portrait photographer. The work of the former then appears as the mere mechanical execution of an inevitable process.

Anyone who has only once experienced an industrial photographer intensely occupied with his task will change his mind very quickly! When he sees how an industrial photographer works with extensive sets of lamps in giant workshops and nevertheless has to struggle with insufficient lighting. When he sees him climbing high scaffoldings, dangerous to life, because the task required it! When he experiences how the industrial photographer has to give directions in workshops where he can hardly hear himself, and perhaps in temperatures, which the regular visitor would find unbearable! When he sees that the industrial photographer had to deal with the respective weather conditions because certain photographs had to be taken under any circumstances! When he has witnessed that the industrial photographer had to put on leather uniforms to go along down into the pits to take photographs in positions completely unknown to the studio photographer! When he sees him not bothered by dust, flue ash, or oil stains, when he sees him disappearing into a still very hot, damaged boiler and returning as if coming out of a steam bath! When he witnessed in person that a task frequently requires use of a large camera, although the exclusive use of a small camera is so tempting because it involves so much less physical strain – while then of course in practice the results would be less »tempting« than the large format photograph. These are some flashes onto the practice of the industrial photographer, who has truly earned his name. And maybe another nerve wrecking circumstance should be mentioned.

The assignment for the industry may require that in order to solve a specific problem, the production is stopped for some few minutes (everything to the smallest detail must be prepared). For the production, »some few minutes« can imply: expenses that go into the hundreds. Nothing must go wrong here. A single mistake has completely different consequences than a studio photographer telling his client »Please come again, the plate had a problem,« or »You moved!« Where the minutes are counted in hundreds, the industrial photographer cannot come up with petty excuses!

Let’s draw a comparison between the portrait photographer and the industrial photographer regarded as second-rate.

(We consciously do not figure into our comparison the truly grand photographers, those of first caliber who represent man. Their achievements are on a completely different level.)

The studio photographer moves a few curtains or turns on his lamps to be independent from exterior lighting condition. The model is »posed!« What counts here is, to a large extent, not the natural pose and movement, but simply how »interesting« the pose is! For if they spend the money, the majority of clients wants to see themselves not life-like, but interesting at all costs. The lighting choice is dependent on this too. The necessary schemes can easily be found in celebrity picture-postcards. And if one has practiced these things hundreds of times, it works without effort. Then comes the well-known »click« of the trigger. And since one has executed the same thing under the same light conditions for years, a (technically) reasonable negative simply must come about. Nothing can really go wrong. And from the [studio] showcases, uniform schemes then look out at the contemplative viewer. He may now be more inclined to recognize that the industrial photographer is not the only one occupied with the representation of »lifeless things (a fact which one likes to degrade him with)! And to be fair, then compare the mere photo-technical difficulties of the industrial photographer with the smooth working process of the portrait photographer:

The latter takes photographs always under the same conditions. The industry specialist simply always has to cope with new contexts: changes in natural light caused by well-known, inevitable factors; daylight mixed with artificial light; or – because nothing else remains – vacu-flashlights or open flashlights, whose effect can never be calculated ahead of time, especially not in giant, more or less dark halls.

Or: Black machines with shiny and mirroring parts against large windows hit by the sun. It borders on mental acrobatics and is often not less dangerous than artistic acrobatics to deal with such conditions in the context of simple photographic technology.

Furthermore, close-ups true to the material require an extraordinary technical skill on the part of the industrial photographer. Moreover: Emphatic aesthetic considerations play a role as well since many industrial photographs are not only used for production purposes but should also have an advertising dimension. All this is usually overlooked when speaking of a »mere« industrial photographer.

Added are the already mentioned physical strains. Who would doubt under such conditions that a successful industrial photographer must probably master his craft (in the broadest sense) in a completely different way than a portrait photographer, who likes to think of himself as an artist and for this very reason regards the industrial photographer (whom he does not deem an artist) as second-rate on the professional scale. This might also be the case because the industrial specialist, like the workers, often cannot remain very clean when he works and takes photographs of dirty things. Dirt from work, however, can make someone lose prestige in the eyes of foolish people. From this point of view (to which one could easily add others) it follows clearly how out of place it is to call a human being, who carries the whole burden of his profession, a »mere« industrial photographer.

But can’t we think of a synthesis between pure portrait photographer and man of the industry? Most certainly! And this question touches on a point which publications on the topic of »industrial photography« have hardly even hinted at. This concerns the true and close-to-life image of the worker and any other craftsman.

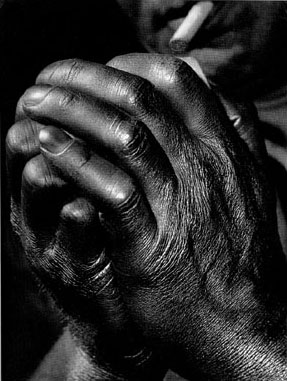

Through his work, the industrial photographer is in constant contact with workers and craftsmen. Often he cannot even manage without their help. Why shouldn’t a few photographs be taken during the breaks, in private, not commissioned? After all it could be possible that a respectable collection of images accumulates. The smallest as well as the largest industries are rich mines for such discoveries. One can find wonderful character portraits everywhere. And the photographer does not even have to sneak up to them. They are just there! And the industrial photographer finds the worker and craftsman in a way that they would never enter the studio: in their working clothes – traces of work on their hands and faces. He encounters him at work, with a machine tool, an anvil, at the melting furnace, or maybe at the fermenting vat of a brewery. And find a worker who would turn down such an offer. But not just the photograph of the whole figure can be inspiring – on the contrary: Working in that direction would imply a general broad scope. Fascinating, however, are those photographs which show the worker in close relationship with »his« machine, the machine he has somehow grown together with. The law of »pars pro toto« (a part for the whole – or put even more precisely: an essential part weighs more than the insignificant whole) leads to entirely terse images that make a strong impression. This also results in interesting visual studies of work psychology. Yet under no circumstances should one just rush to shoot photographs – first one should observe, and then observe again. That can always be done with only a few glances. The image should first take shape in the photographer’s imagination, then he should begin to shoot. A moment which the camera caught too soon will often lack the necessary concentration in the image. It is not necessary to use a high-speed camera: Success stems not from the technology but from handicraft skills and psychological intuition.

The climax, however, is the full-image character portrait, captured with nuanced empathy. It is not difficult to imagine the effects of a portfolio of such photographs! The attempt to capture simple human beings in a systematic and grand way was already made once: This was Lersky’s book Man in Everyday Life. If this book did not have a great impact, this was the case because Lersky did not take the people as he found them: grand in their simplicity. Rather, he treated them like a moldable mass, made them will-less and then captured them in the way in which he wanted to see them.

For twelve years it has been sermonized that only the peasant can still have an unspoiled, expressive face – this sermon was methodical, we were flooded with images of peasants – we were served images of farmers on any suitable or unsuitable occasion. This ruthlessly calculated and sentimentally served spook is over. What remains is the insight that the huge army of craftsman and industrial workers probably includes a larger percentage of characteristic faces than these peasants!

It would be a nice private task of the industrial photographer to prove this viewpoint.

Don’t believe the peasant was so content with himself that he disliked any posing! On the contrary. The industrial photographer avoids this danger with his models when they see him as their working pal. In the event of a more distanced relationship to the models, it is only the art of treating humans that surely leads the industrial photographer to his goal.

Little needs to be said about technique. The industrial photographer, who has mastered other things, will hardly find it difficult to solve the technical problems of his portraits.

This is important: the background should either be part of the image, or it should be as restrained as possible – one can always find a plain wall. A good visual effect is destroyed by unfocused planes floating around in the background. The worst fear one might have, however, is contrast! One should not shy away from strong lights and crisp shadows – they work out the facial expression in a completely different way than a broad, leveling frontal light. Unlike Ortho-Material, Pan-Material tends not to render shadows lacking detail. It cannot be denied, however, that an Ortho-Layer can be advantageous given our task: it models the skin more strongly than a Pan-Layer – and it is precisely strength that we want to see here, we do not want to see faces bleached by red sensitive material. And a certain hardness which the lens creates is more characteristic of the working people than a softness!

Certain purely aesthetic aspects of the image cannot and should not be overlooked in this context! The image of industrial man, too, should first and foremost have a visual effect, it should capture the viewer’s gaze! The first precondition then is unquestionably the existence of a visual idea. Without such an idea, a technically perfect photograph cannot be anything but a simple representation (which one sees and instantly forgets). Yet the visual idea is not the only requirement – there are additional, purely formal requirements. The image attains strong tensions through a well balanced distribution of tones (light and dark) and through symbols of movements, which must be captured at their climax. These strong tensions make the images stand out easily from the mass of many, too many images. The effectiveness of a close-up was already noted above. This close-up works decisively against the general shallowness which is often connected to photography. – One of the most important pictorial elements is the lighting! Hence again here the stress against the fear of contrast! But it must easily be visible, where the light is coming from. A sure-footed (also technical) mastery of contrast is a precondition taken for granted. Take for example the extraordinary achievements of Dulovit! An obvious and indecisive wavering between contrast and even lighting is unbearable. A light that casts crisp outlines wonderfully works out the character of a face – broad frontal light will result in nothing more than a large-scale passport photograph! Above all this should be followed: Pay attention, and pay attention again to the face as a mirror of the soul. The pure industrial photographer always runs into one danger: What may be truth to the materials with respect to machines easily leads to vivisection with respect to human portraits. This vivisection destroys all expression, the expression which originates from the inner life of a human being.

Photography of the Proletariat: A note on files and documents concerning the history of worker photography

Wolfgang Hütt, Die Fotografie 8/1960

Among the files of the Leipzig City Archive, there is a file catalogued as Chapt 35 No.1500. Conscientiously and clearly written on the lid is written: »Association of German Worker Photographers, Local Group Leipzig.« Whoever opens the file will find a brief yet significant correspondence as well as protocols from two meetings of the Leipzig City Council. Included also in this file is a copy of the magazine The Worker Photographer, the organ of the Association of German Worker Photographers. It dates from 1928, the same year in which file Chapt 35 No. 1500 was made.

At this time, the Local Leipzig Group of Worker Photographers asked the city council for a heated room with water and electrical light. They also asked for permission to set up a darkroom in this room and to use light and water for their photographic work free of charge.

The supply with sufficient means to support the photo groups of the workers is one of the many things which can be taken for granted in the GDR. Those workers who petitioned the Leipzig City Council on July 23, 1928, however, did not live in a workers’ and peasants’ state, but in the class state of the Weimar Republic. The correspondence between workers and the city council member, between the latter and other local officials, which took place through the late fall of 1928, shows clearly how little the bourgeoisie was interested in developing and maintaining worker photography. Due to many hesitations and excuses, the decision was continuously postponed. Once the matter was brought to the city council, it was »democratically« rejected.

The protocol of one of these meetings is particularly interesting. While the communist faction supported the petition, the social democrats sided with the bourgeois faction. Their argumentation even gave the bourgeois factions the desired reasoning to reject the petition of the worker photographers supported by the communists. Thus, the speaker for the committee explained to the meeting of the city council that »a representative of the social democrats expressed the opinion in the committee: Once we make a room available to this worker photographer society at the expense of the city, any rabbit breeder society could come along as well to ask for such a room… The petition made in the committee by the communists requires examination, and also consideration, but in order to be of consequence the petition should be rejected.«

This procedure is remarkable because it clearly outlines the class position of the worker photographers. They belonged to the class conscious, revolutionary proletariat and had nothing in common with the social democrats’ revisionist agendas for worker education. It is astonishing how little is known today about this movement, after more than thirty years – about a movement which was fiercely rejected by the bourgeoisie, a movement whose significance even the social democrats could not deny later on and which found public recognition even among bourgeois photographers.

It is not an accident that the literature on photography has until today not taken on the history of worker photography. This literature, until a few years ago regarded as a bourgeois monopoly, supported the class aims of the ruling bourgeoisie. It was in their interest to deny anything within photography that did not serve the bourgeoisie or that was even used in the battle against the ruling bourgeoisie. In this way, and not accidentally, an air of forgetting surrounded a highly contemporary chapter of the history of photography. Fascism and war destroyed many valuable documents of worker photography.

Many a worker photographer may have fallen under the guillotine of the blood judges, and others have fallen since. Those few who are still alive do not make a big fuss about their work and their struggles. This is actually regrettable, for how much could they teach us!

The Association of German Worker Photographers was founded in August 1926, led by the editors of the AIZ (Workers’ Illustrated Newspaper). The magazine The Worker Photographer appeared as the organ of the Association. Aside from technical articles, which served to qualify amateur photographers of the working class, articles appeared which treated the ideological fundamentals of photography. In addition, workers were able to publish successful photographs of their life in this, that is »their« magazine. The necessity of the founding was laid out in an article in the AIZ of August 24, 1926. Here it says: »So far worker photographers exclusively practiced their secondary occupation for the pleasure of a small circle of relatives and acquaintances. The development of the press today gives them the task to communicate their photographs as worker photographers to the masses of the working class… The workers’ press cannot do without workers’ correspondents. Similarly, the illustrated newspapers (AIZ, The Red Star) can definitely not do without the collaboration of the working people. A strong organization of worker photographers must now counter the bourgeois photography correspondents.«

Taking into account the social situation under bourgeois rule during the Weimar Republic and the then erratic development of photographic technology and chemistry, it becomes clear that the creation of a strictly organized worker photography was not only possible during these years, but even necessary. For decades, there was only a bourgeois amateur movement. For decades, the proletariat was excluded from the photography movement, given their lacking of financial possibilities. Now the photography industry began to search for new customers for their products. The amateur movement, guided by the bourgeoisie expanded and increasingly accommodated workers. Were they meant to become bourgeois as photographers? In addition, the bourgeois press carelessly used photography in this sense. The proletariat was forced to recognize the significance of photography for the class struggle.

Hence, the movement of worker photographers originated in objective conditions. It was only possible on the basis of the organized, class struggling proletariat, which consequentially continued the legacy of Marx, Engels, and Lenin. In this sense, Fritz Langenbuch was right when looking back in the May 1928 issue of the Worker Photographer, writing that all associations of workers and worker newspapers are not »made« but originate out of the necessity of political life. »Made« meant the way in which bourgeois newspapers and magazines came about based on a rich flow of capital. The Association for Worker Photographers and their organ, The Worker Photographer had,« by contrast, »neither money nor advertisements from the beginning on, as is common. They only had the new idea which corresponded to the struggle for the future, the grand goal, the camera as a weapon.«

Due to the class situation, the photographs created by the conscious proletariat became, in many cases, accusations against the ruling bourgeois order. No. 129 dating from November 1926 of Industry Protection, the magazine of the Association for the Protection of German Industrials, contained an article dealing with worker photography. It equated the practice of the worker photographers with industrial espionage. It tried to put them on the same level as criminal derelicts and advised company owners to prohibit photography on their premises. This fact proves that photography was a means of proletarian class struggle. It proves how right the workers were in using photography in their struggle for freedom and against unbearable exploitation. It proves how effective their photographic creations became in a very short period of time.

Despite the resentment of the bourgeoisie, No. 5 of The Worker Photographer could already report a significant expansion of the association. At this moment, local groups already existed in Berlin, Elberfeld, Halle, Leipzig, Dresden, and in many other cities. Taking stock, the AIZ wrote on February 24, 1927: »The worker taking photographs today operates side by side with the political writer and speaker. His productions belong to the epistemological and cultural equipment of the working people, just like the daily newspapers and the spoken word. With his camera, the worker photographer grasps the salient images from his social, economic, and political life. His language is plastic in its truth and objectivity.«

Worker photography was also respected within the local press. It made an effort to instruct photographers in their ideological efforts. Felix Lange wrote in the Saxon Worker Newspaper of April 28, 1928, appearing in Leipzig: »If he (the worker) wants to use his achievements to the benefit of his class comrades, the selection of motifs is and remains most important. It is particularly important to capture the effects of bourgeois politics and capitalist rationalization… As much as possible, the struggle of the working class must be captured on plate, as expressed in meetings, demonstrations, strikes, etc. We must honestly state that photography cannot sink to the level of a mere hobby. Instead, we must exploit photography consciously in the struggle for the demands of the working class. The behavior of the employer associations proves that we are on the right track. They are sickened, because they do not want anyone to look at their cards…« Only a few years passed, and worker photography had gained respect and reputation, in addition to the hatred of the class enemies.

The local groups organized widely received exhibitions. Expert circles recognized the Worker Photographer. The bourgeois Frankfurt Newspaper confirmed that the Worker Photographer was way beyond the level of a mere society organ. Even the Leipzig People’s Newspaper, which so many times had stabbed the struggling workers in the back through its blatant reformism, had to admit on April 12, 1928: »The Association of Worker Photographers has existed only for one and a half years and already today has gained worldwide reputation and shows worldwide effects. Its aspiration to teach the worker more than mere snapshots, to teach him to handle the camera correctly in any situation, has transformed photography from a privilege of well-to-do circles into a weapon in the ideological struggle of the proletariat. The photograph becomes a political report within the class struggle if the class conscious worker securely manages to capture the world in his camera.«

Hence the worker photographers went from triumph to triumph, despite all resistance. When the Dresden group showed its first exhibition on the occasion of its first anniversary, it already had forty members. Two thousand visitors saw the exhibited images. The obvious tendency in all works revealed that these worker photographers were completely conscious of their task.

»Corresponding to the character of its members,« the then bourgeois Dresden News wrote, »images of work filled the space. Scenes of work on the street, the home industry or in the factory were captured by the camera. Many a photograph taken inside and difficult to produce testified to the abilities of the photographer. One part of the exhibition showed images of the prevailing hardship, especially of housing shortage. Numerous images of the life of a child, sports events, recreation hours, and hiking days were cheerful. An essential part of the photographs was of virtually artistic perfection.«

It is still too early to make definite judgments about the artistic merits of worker photography, because very little of the transient material that has survived the night of fascism has been accumulated. But it can be said already today: Given the consistency of social insight, and given the resulting content and photographic form, worker photography reached an artistic peak. This put it in a position equal to the great traditions of the democratic bourgeoisie which was still dedicated to humanist traditions. Worker photography surpassed it by far, however, in terms of its truth content. We must know that the proletarian past bears an essential part of the legacy of photography that we must preserve and appropriate. We face the task of filling this great gap in the history of photography, before even more documents are buried.

Path and Goal of Amateur Photography in the GDR

Gerhard Henninger, Die Fotografie 8/1960

The amateur photography movement of the GDR has experienced a heightened social status. This has become clear since last year, especially since the preparation of the second Bifota and the discussion about its principles. How has this status expressed itself?

First: Under the new social conditions created through socialist organization, it has become possible to lead the practices of amateur photographers beyond mere hobby. Hundreds of thousands camera owners take photographs today, for pleasure, relaxation, and recreation – and we welcome this hobby. Yet we do not stop there. The immediate cause for many camera owners to join a photo group is their wish to learn to photograph »better.« Many wish to hear about experiences, methods, and recipes to make it easier to take photographs. Our groups must meet those demands, must pay attention to teaching techniques of photographic work.

Yet we recognize the possibility of an artistic character of photography, and we consciously reject the reduction of photography to an exclusively technical procedure. As such, we make it possible for our groups and clubs not merely to teach technical capabilities, but to lead many so called »snap-shot photographers« to a laymen’s artistic practice. It is necessary to convince the advice-seeking »snap-shot photographer« in our groups, that good photography does not only consist of chemical recipes and good cameras, but also of a conception of a content, of an ability, in order to connect photographic seeing and social seeing and to recognize and design the essence of an appearance. Each amateur faces an aesthetic problem when he first looks through a camera and chooses an object, whether he is conscious of it or not. Hence we do not fight against the hobby. Instead, we build on it in order to use existing pleasures and excitement to awaken and foster dormant talents and capabilities for artistic creation in each human being.

Second: The heightened social status finds expression in the immediate mass effects of amateur photography. Photography is able to reach large groups of people quickly and intelligibly – in small and large exhibitions in factories, villages, and cities, as well as in factory- and village-newspapers. Under our new social conditions, photography, for the first time, completely serves to communicate and propagate the great humanist ideas of peace, of friendship among the peoples, and of human happiness. The direct consequence for the practice of our amateur groups is to enhance the amateur’s responsibility for the meaning and effect of his images. The less the amateur takes photographs just for himself, the more he takes photographs to communicate his thoughts, feelings and opinions, his experiences and perceptions, the more he lets others participate in them and generates similar thoughts and sensations. The stronger and faster that his creations grow out of the private and individual sphere, the stronger and faster his artistic effort and lay-artistic practice will become socially effective.

In its social effects, our amateur photography becomes an organic component of political work with the masses. Hundreds of amateur photographers now work to give artistic form to the life of the comrade in the diaries of the socialist brigades. Hundreds of amateur photographers have already begun to shape the socialist reorganization of agriculture in photo-artistic terms. They do so through their participation in village chronicles.

Hence amateur photography fulfills a double function: By means of art photography, it creates an excitement for our new life in all its variety, it shows the new socialist man. Furthermore, as photography is consciously practiced artistically by hundreds of thousands of workers, it educates these people, gives them true standards for the beautiful and artistic, develops their faculties of aesthetic perception and judgment, facilitates the reception and understanding of great works of art.

Third: The more we include so-called beginners in the artistic process, the more we get them to capture and photo-artistically shape the essence of our life, the smaller the principal difference will be between their practice and that of the advanced photoartist, the more we begin to bridge the seemingly unsurpassable gap between both, despite their different levels. As the recent exhibitions have proved, the number of amateurs exhibiting highest achievements is rising. It would be wrong today to still regard amateur photography as a type of photography which is by principle of lower quality. How often are we inclined to sneer at an amateur who considers an image beautiful which should be rejected as kitschy! Of course we have to overcome kitsch, of course we are not allowed to give in to the »bad average.« Yet we often forget that to overcome the after-effects of the capitalist past and the conscious deterioration of the artistic abilities of the masses, aesthetic education is a process that must be promoted and supported with determination.

Under the influence of the arrogance of circles isolated from the life of the people, we have in the past years not paid attention to several key questions, which are of importance to the practice of our group work. I am thinking here for example of the question, what an amateur should take photographs of. Some friends still think that they must turn to far fetched themes and subjects which at some point were praised as art – under the influence of the intellectual acrobatics of a few so-called artists who mistakenly describe themselves as »modern.« This caused virtual epidemics among our amateurs in the last years: the puddle and cobblestone motifs, the laundry line motifs, the window pane motifs etc. We forgot that it is best to begin with the artistic forming of those themes and subjects that the amateur can quickly learn, can best judge and evaluate: his own practice within production, his life in the brigade, within the family, his holidays, his recreation, his sports. Many new social phenomena are developing especially in this area, for example, socialist naming and marriages, brigade evenings and cooperative meetings. Given these conditions, is it right to condemn the »family photograph«? A few years ago, the exhibition The Family of Man already pointed to the great possibilities which can be expanded significantly under the new social conditions of socialist life.

A third characteristic of our new amateur movement, then, is its close connection and transition between high »art photography« and lay-artistic photography. Only the conscious and determined advancement of amateur photography, its distribution and rise of status, nourish high photo-artistic achievements.

Fourth: In the spirit of the Bitterfeld conferences – parallel with all other artistic areas – our amateur movement leads to a broad mass movement of artistic creation of the people, which gives all talents the possibility of their full development. The occupation with art becomes an essential characteristic of the new socialist human being freed from capitalist exploitation. Already today, the worker and cooperative farmer who take photographs stand next to the writing, painting, singing, and music making worker. What a principal difference to the petit-bourgeois amateur movement of earlier decades, which often drifted off into clubbiness, or which regarded photography and hobbies as an escape from an unsympathetic present. Our new creations serve to render our present and our life even more beautiful, serve to connect us to our life even more tightly. As such, our amateur movement strives for a high goal, which would have been unheard of under earlier social conditions in Germany. Here lies the national significance of our new amateur movement.

Concerning the Question of Socialist Realism in Photography

Dr. F. Herneck, Die Fotografie 8/1960

In Lessing’s Emilia Galotti, the painter Conti deplores the fact that one cannot paint directly with one’s eyes, because much is lost on the long way from eye through arm to brush. According to Lessing’s opinion, here presented through Conti, the eye of the artist is of central importance to the visual arts: Raphael would have been the greatest painting genius, even if he had unfortunately been born without hands.

The opposition of eye and hand, which plays a significant role in the classical visual arts, is largely suspended in the photographic arts. The photographer is indeed able to paint directly with his eyes – a fact that is essential in evaluating photography. Photography is a way of practically appropriating reality, a means of knowing and changing the world. Art, according to Helmholtz, means to »translate« nature, not simply to copy it. To this end, one has to choose that which is generally significant, and eliminate that which is not essential and accidental. The question whether photography can be art has to be answered based on its ability to typologize. Several artistic achievements of famous photographers – from D.O. Hill to Helmar Lerski – have long proven, that photography is art.

A realistic art of photography that consciously uses all means of photographic typologizing – like the choice of vantage point, lighting, focus, aperture, blurred movements, etc. – can only develop in a two front battle: in the battle against formalism and naturalism. The battle against formalism, as expressed in so-called subjective photography and other expressions of the decay of late bourgeois society, is a form of ideological class struggle. Formalism means the renunciation of representational content. Subjective photography, as all other formalist pseudo-art, denies the epistemological character of artistic creation. By disregarding content, it necessarily leads to the destruction of photographic form. Formalism clearly fulfills a reactionary class function, in photography as well as in the visual arts. However, it is remarkable that the representational character of photography makes its misuse for formalist experiments more difficult. Hence subjective photographers are forced to resort to »photographic« means, that is, to certain tricks of mechanical-chemical follow-up processes.