People rarely call the Photographic Resource Center by its full name. Instead, it's just 'the PRC.' The informality of the initials emphasizes how uninstitutional an institution the PRC is. -- Mark Feeney, Boston Globe, 2006

Introduction, some words on the occasion of an anniversary

John P. Jacob, New York City, 2006

I became involved with the Photographic Resource Center in 1981, when an exhibition of my photographs in Portland, Maine, was reviewed in volume III, number 1 of Views: the New England Journal of Photography, and my photographs appeared on the front cover. The PRC was five years old and I was just out of college.

The PRC had been founded as an artists’ space, and it was part of a network of similar institutions, most of which have long since disappeared, where new and experimental artwork was being made and shown. The PRC hosted a conference on artists’ books, and Dutch artist Jan Henderikse and I rented a table together to show and sell our work. PRC curator Anita Douthat was organizing important exhibitions in photography, and I traveled often between Boston and New York to see them.

In the mid 80s, after my photographs were included in a group show in Budapest, I began to exchange artwork with photographers from Eastern Europe. I traveled to Hungary for the first time in 1986 to organize a show of my Eastern European “collection” at the Liget Galeria in Budapest, and Dana Friis-Hansen, then curator for the List Visual Arts Center, invited me to prepare an exhibition of Eastern European photography at MIT. I also organized a corollary one-person show of work by Polish photographer Anna Bohdziewicz for the PRC, which Gary Metz then presented at RISD. PRC Deputy Director Jean Caslin invited me to be a juror for the PRC’s grant sponsorship program in 1987, and I wrote my first article for Views, edited by Dan Younger. I continued to travel to Eastern Europe and the USSR throughout the ‘80s, and in 1988, in a weird twist of fate, I relocated to Austin, Tx. and Jean Caslin moved to Houston. I organized an exhibition of Hungarian photography for her organization, the Houston Center of Photography, and also wrote for its journal, Spot. In 1989, I organized an exhibition of “fire-prints” by Hungarian artist Tibor Várnagy for the PRC, and In 1990, I returned to graduate school in Indiana. My daughter was born that year, just a few days after the opening of an exhibition of photography from the USSR that I curated for the List Center, featuring the first US presentation of Boris Michailov. Then, as I was completing work towards my MA, Anita Douthat announced her plan to leave the PRC. I applied, had a phone interview with Jim Stone, and a few days later Brenda Sullivan called to offer me the position of director of exhibitions. I re-located to Boston with my family in fall 1992.

My involvement with the Photographic Resource Center, from summer 1981 to Winter 1999, spanned nearly twenty years, so to say that the PRC has influenced my career is an understatement. Nevertheless, it’s difficult to speak of a “favorite memory” of the PRC because not long after I arrived things began to fall apart. Whatever good I may have achieved for the PRC, all of it was born of crisis, and along the way I lost much that was important to me. What I can say positively is that without the generosity of the community, and the support and hard work of a few key individuals, the PRC would not have survived the crises of the 1990s. One of those individuals was Robert Seydel, who had been hired as coordinator of educational programs not long before I arrived and became curator after I became director. Working with Robert was the most rewarding experience of my career; our conversations then continue to shape the work that I do today. Of all my memories of the PRC, the one that replays most often and most vividly is that of standing with Robert at the front desk in the PRC lobby on the day when we became the organization’s last remaining staff.

At the end of the 1980s, public funding for the arts began to slow just as the PRC’s programs were expanding, and the organization found itself in a financial crisis. Eelco Wolf, who had been president of the Board of Directors, took over as Executive Director and paid down the debt. He did not restructure the organization or its programs though, and when I was hired there was a feeling of confidence among the staff and Board that corporate funding would fill the gap left by diminishing federal and state support. In spite of Eelco’s efforts, and those of Brenda Sullivan, whom he recommended for the position of director after his departure, that confidence proved to be ill-founded. At the same time that state and federal funding for the arts were all but eliminated in the early 90s, and corporate support remained elusive, the PRC’s remaining debt came due and the bank would not re-negotiate. The PRC simply ran out of money.

I had been at the PRC for just over a year when Brenda told me that she had submitted her resignation to the Board, and that she’d recommended me for the position of director. It was a situation that I had feared but an outcome I had not anticipated – a career change for which I had neither the ambition nor the training. The Board called an emergency meeting and Dan Younger and I were invited to contend for the directorship by presenting our plans to save the PRC. Neither one of us was considered up to the challenge though, and the Board asked Chris Enos to step in instead. We were told that she was the only person fierce enough for the job.

Chris and I disagreed on how to move the PRC forward, and I guess that she’d have let me go promptly had she not also been teaching full time at UNH, and had no time to organize and hang shows. Without shows there could be no audiences, and without audiences there could be no PRC, so I continued to work. However, the PRC’s quarterly journal Views was effectively defunct, and its printer owed for multiple previous issues, so Chris fired Dan. Then, on learning from Brenda that she had not cashed her own paychecks for several months in order to ensure that there would be sufficient funds to pay the remaining staff, Chris threatened to cancel the outstanding checks. While Chris was out of the office I examined the PRC checkbook and, having determined that the balance was sufficient to cover the debt, phoned Brenda to tell her to deposit her checks. Chris called an emergency meeting of the Board and resigned on the spot, and the PRC’s membership director announced that she would be leaving too. Then, concerned that they might be liable for its debt if the PRC were to close, several Board members submitted letters of resignation. With limited options and reluctance on both sides, the remaining Board members offered me the position of director. And that is how, not long after arriving at the PRC, Robert and I came to find ourselves standing at the front desk, the offices empty and the galleries dark. We resolved to accept the challenge and, if possible, to enjoy ourselves in the process.

Barbara Hitchcock, director of corporate cultural affairs for Polaroid and then a recent recruit to the PRC Board, and Rose Austin, former director of the Mass Cultural Council, are the two other individuals whose support was instrumental to the survival of the PRC in the 1990s. At a moment when others were turning away, Barbara agreed to become Board president, and she remained in that position throughout the difficult years of restructuring. Barbara’s delicacy compensated for my bluntness, and her resolve was a counterpoint to my untrained blundering. Rose, who should have taken a long and much needed rest after her difficult years at the MCC, succeeded Barbara as president, and brought personal strength and organizational capacity to the Board. Barbara and Rose encouraged me to find and follow my own vision for the PRC, and they stood behind me over the time it took me to formulate that vision and make it real.

Within a remarkably short time exciting things were happening. Robert’s Conversations Towards the Third Millennium brought a renewal of NEA funding and a truly amazing array of participants; my second application for operating support from the IMLS was granted, guaranteeing our salaries for two years; and I received a fellowship to attend the Getty’s Museum Management Institute to learn how to think and behave like a director. A re-organized Board worked with PRC staff to re-write the organization’s mission statement; the PRC logo was re-designed; and the Benefit Auction exceeded all expectations. The Godowsky Award was revived and brought new photography from Asia and Africa to the PRC; Dennis Hopper exhibited and Lou Reed, Patti Smith and Michael Stipe performed benefit events; my exhibition of photography from East Germany was reviewed by Vicki Goldberg in the NY Times; and the Photography in Human Experience program, a product of our conversations that was launched after Robert left the PRC, invited artists from the community to work as curators. The PRC’s debt, which had exceeded two times its annual budget, was paid off, and, to everyone’s surprise and delight, we celebrated the PRC’s 20th anniversary in 1996. Robert and I worked, often around the clock, and the slow but steady revival of the PRC was both our reward and our punishment.

Gradually, the work stopped being enjoyable. The Board never fully accepted the job of fund-raising for the PRC, and finances remained uncertain. Barely capable of meeting payroll on schedule, staff turnover remained high, and I often found it necessary to borrow against my own credit card to ensure salaries. My (now ex-) wife complained when, year after year, I had to work on Mothers Day, and Pam Allara, then president of the Board, complained when I brought my family along to weekend social events. The end of the PRC’s lease with BU loomed as an ever approaching threat of futility; secret meetings with MassArt and Northeastern went nowhere. Increasingly, I found myself trying to maintain a balance between the popular programs that would keep the PRC afloat and those that would perpetuate its reputation as a visionary organization. Robert said that I was making decisions based on survival rather than integrity, and left to devote more time to his artwork; he took a position at the University of Connecticut and later settled at Hampshire College. He was right. I lasted for a few years longer, but the stress was such that by the time I submitted my resignation, in late 1999, I was prepared to abandon my career altogether rather than take on another directorship.

What I remember now is that during my eight years at the PRC I cried twice; once when Brenda told me that she had resigned, and once again when I told Terrence Morash, whom I had just hired and who didn’t deserve to be left to his own devices so soon, that I had resigned. But Terrence was better equipped for the situation than I had been, and I have admired from a distance the steady growth that the organization has enjoyed under his leadership. More of the same is what I’d wish for the PRC, and more money to support it as it grows.

After leaving Boston, on New Years Day 2000, I lived in Maine for two years and developed the Photography Curators Resource, a network and database for curators working with photography. My marriage of nearly twenty years dissolved, and in 2003, after a lot of long-distance commuting, I accepted a position as director of the Inge Morath Foundation in New York City. The Foundation offers a good mix of administration with the curatorial work that I enjoy, and is flexible enough to allow me to work on other projects as well. Those projects include several forthcoming books with the Steidl Verlag in Germany, and exhibitions from the archives of the American Society for Psychical Research and the Man Ray Trust, both in New York. I have also re-married, and my wife is a former PRC Board member.

All’s well that ends well.

Key exhibitions & events, 1992 – 2002

1992

Message Carriers

Theresa Harlan, curator. Work by Hulleah J.Tsinhnahjinnie, Patricia Deadman, Zig Jackson, James Luna, Jolene Rickard, Richard Ray Whitman, Carm Little Turtle, and Larry McNeil. Companion exhibition People of the First Light, curated by Russell Peters

Camera as Weapon: Worker Photography Between the Wars

Leah Ollman, curator

From the Fallen Ash: Landscapes of Hawaii, Iceland, and Costa Rica

John Jacob, curator. Laura McPhee and Virginia Beahan photographs of Iceland, Hawaii, and Costa Rica

1993

Out of Control: Photography from East Germany

Online anthology, John Jacob and Karla Sachse, editors

Striking Images

John Jacob, curator. Photographers focused on the subject of baseball, David Spindel, Danielle Weil, Slobodan Dimitrov, and Jim Kiernan

Other Africas: Max Belcher, Fazal Sheikh, and Vera Viditz-Ward

John Jacob, curator

I Have a Dream: 20th Anniversary Exhibition of Photographs from Martin Luther King’s March on Washington for Jobs & Freedom.

John Jacob and Steven Kasher, curators

1994

Lucinda Devlin: Death Chambers

Robert Seydel, curator

Photographs by Dennis Hopper: 1961-1967

John Jacob and Robert Seydel, curators. Companion exhibition, Bill Burke: Minefields

Art Works: Teens and Artists Collaborating on the Polaroid 20×24 Camera

Robert Seydel, coordinating curator with The Education Project, NY. Teens from New York City family shelters, drug treatment centers and city housing in the South Bronx and Lower East Side were paired with artists Chuck Close, John Divola, Felix Gonzales-Torres, Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, Hakin Raquib, John Reuter, Andres Serrano, Laurie Simmons, Carla Weber, and Jean Vong

Fire Without Gold: Documentaries of Photographers of Color

Miriam Romais and Robert Seydel, curators. Work by Eli Reed, Marilyn Nance, Miriam Romais, Ricky Flore, Christine Jackson, and David Lee

Return and Exile: Sylvia Plachy’s Photographs from Central Europe and Susan Rubin Suleiman’s Budapest Diary

John Jacob, curator. Rubin Suleiman and Sylvia Plachy were featured together in an exhibition that explored the experience of an exile returning to her native homeland. The two left Hungary in 1949 and 1956, respectively seeking personal and political freedom in the United States. Years later they both returned to Hungary, each recording the memories, emotions and thoughts connected with the country of their youth, Suleiman with words and Plachy with photographs

Conversations Toward the Third Millennium, I.

Discussion series co-coordinator with Robert Seydel. Participants included: Sylvia Plachy and Susan Rubin Suleiman; Agnes Denes and Suzi Gablik; others

1995

Photographs from a Pilgrim’s Place by Kevin Bubriski

Robert Seydel, curator

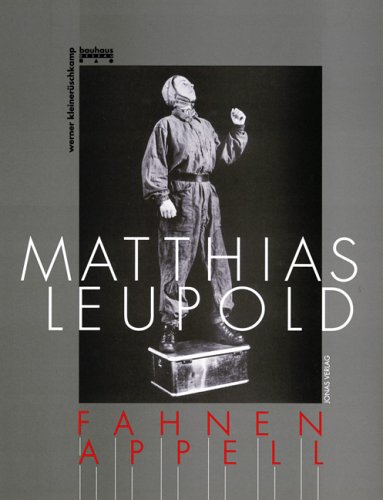

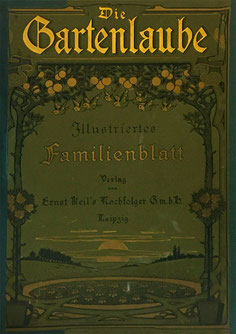

Matthias Leupold: Fahnenappell and Gartenlaube

John Jacob, curator. Companion exhibition, Bela Kalman: A Life in Photography

Museum Collections on the Internet (paper by John Jacob).

Photography Think Tank I: Going Outside Art Histories, Alison Nordström moderator, Southeast Museum of Photography

Between Spectacle and Silence: The Holocaust in Contemporary Photography

Robert Seydel, curator. Work by Joseph Biel, Richard Kraft, Aharon Gluska, Barbara Rose Haum, Melissa Gould, and Tatana Kellner

The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning

Robert Seydel and James Young, curators

Articulations of History: Issues in Holocaust Representation

John Jacob and Robert Seydel, conference co-coordinators. Participants included: Michael Berenbaum, Andreas Huyssen, Lawrence Langer, Ellen Rothenberg, Jerome Rothenberg, Nancy Spero, Susan Suleiman, James Young, and others

Conversations Toward the Third Millennium, II.

Discussion series co-coordinator with Robert Seydel. Participants included: Noriko Fuku, Uriko Saito, and Stephen Kellert; Lawrence Weschler, Lewis Hyde, and Rosamond Purcell; others

Selected Projects From the Arts Educators Coalition Exhibition

Robert Seydel, curator. A celebration of independent arts educators under the PRC’s umbrella. Coalition members Alan Bush, Bob Kramer, Nicole Burkart, Brad Mintz and Janice Rogovin each had students included in the exhibition

1996

The Land of Paradox: Japanese Landscape Photography

Noriko Fuku, curator. Work by Yuji Saiga, Norio Kobayashi, Toshio Yamane, and Naoya Hatakeyama

Antic Meet: Merce Cunningham and the Visual Arts

Robert Seydel, curator. Companion exhibitions, Bodies Descending: the Dance Photographs of Philip Trager and The Boston Ballet by Jerry Berndt

1997

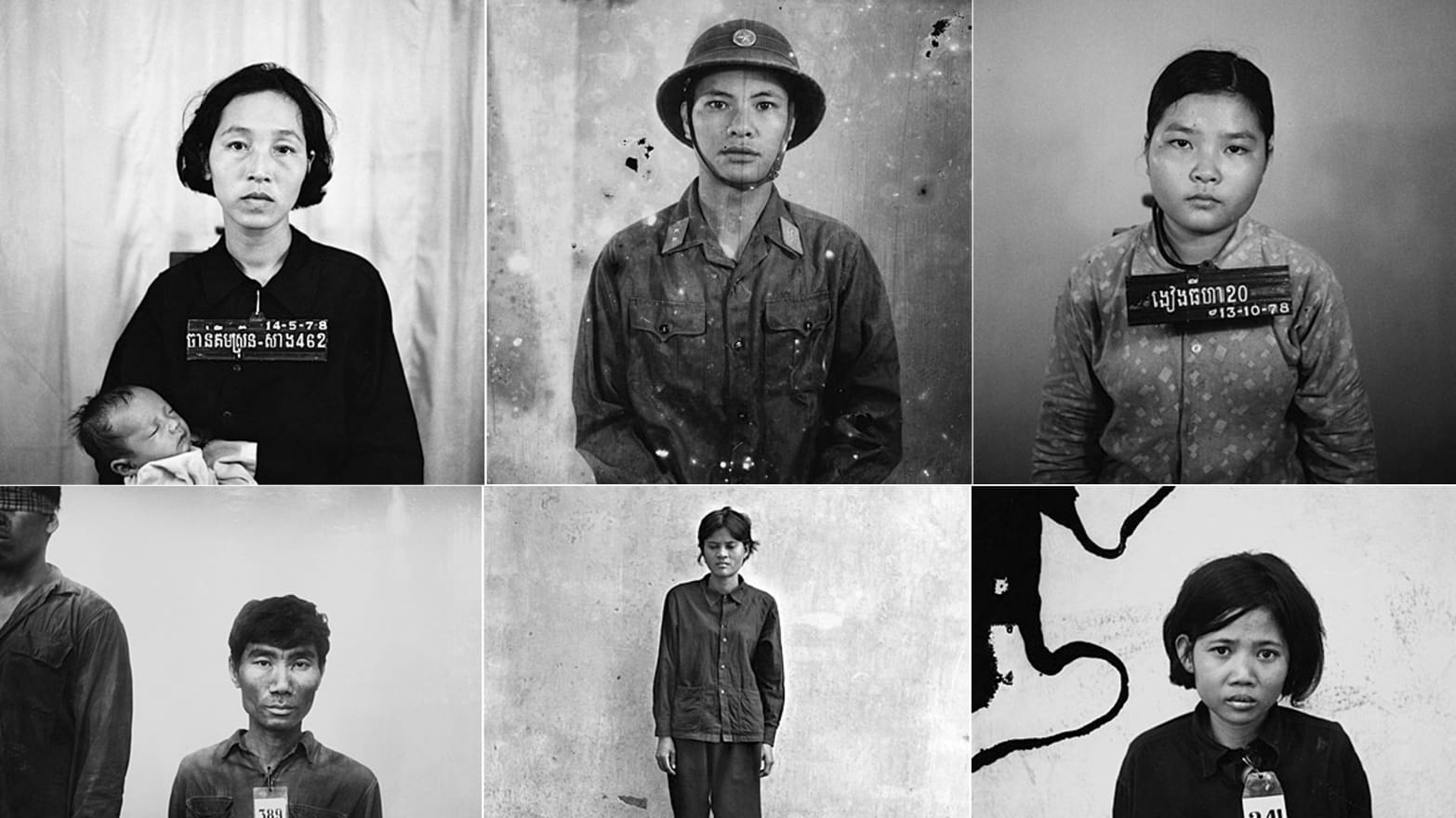

Facing Death: Portraits from Cambodia’s Killing Fields

John Jacob and Robert Seydel, curators.

Portions of the PRC-sponsored traveling exhibition showed at the Ansel Adams Center for Photography in San Francisco and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Facing Death was also published as a monograph by Twin Palm Publishers

Anxious Libraries: Photography and the Fate of Reading

Robert Seydel, curator. Work by Jerry Beck, Gillian Brown, Ron DiRito, Mark Alice Durant, Emmet Gowin, Rick McKee Hock, Maria Martinez-Canas, Susan Meiselas, Abelardo Morell, Clarissa Sligh, and Michael Spano. Companion exhibition, Le Lecteur (The Reader): Selected Works by John O’Reilly

Extended Play: Between Rock and an Art Space

John Jacob, curator. Companion exhibitions: The Velvet Years, 1965-67: Warhol’s Factory, Photographs by Stephen Shore (traveling exhibition); Velvet Rarities: From the Collection of Jay Reeg; Picture and Sound: Music Photography by Kathy Chapman, Michael Greco, B.C. Kagan and Phil in Phlash; and Being There: Photographs by Billie Perry and Karen Whitford

1998

Eleven Artists

John Jacob and Robert Seydel, curators. Work by Roswell Angier, Paul D’Amato, Susan Erony, Hilary French, Henry Horenstein, Jennifer Munson, Neal Rantoul, Anne Rearick, Janice Rogovin, Michael Silver, and Carrie Trippe

Two Times Intro: Photographs by Michael Stipe, Drawings by Patti Smith, and Polaroid Prints by Oliver Ray

John Jacob, curator. The continuation of the Between a Rock and an Art Space theme featured drawings by Patti Smith and Polaroid prints by Oliver Ray as well as a visual diary of Stipe’s experience as a musician and practicing visual artist. Stipe’s photographs followed the lead singer and songwriter for the band R.E.M. and Patti Smith as they toured with Bob Dylan in 1995

1999

Recollecting a Culture: Photography and the Evolution of a Socialist Aesthetic in East Germany

John Jacob, curator. This exhibition studied the “political and economic pressures on the visual arts of the German democratic Republic.” The photographs were chosen from two state-sanctioned photography journals from East Germany, Fotokino and Die Fotografie. Previously unexplored, the archives were a rich resource that allows us to examine the history of East German photography and the use of visual imagery during the 50-year period of the state’s existence. Although some of the images were previously published in the journals, they have never before been presented in an exhibition. In 2000, the exhibition traveled to the Hampshire College Gallery, hosted by Robert Seydel

Dramatis Personae:

A Look at Role-Playing and Narrative in Contemporary Photography

Sara Dassel, curator. Work by Renee Cox, Lyle Ashton Harris, Thomas Allen Harris, Nicholas Kahn, Richard Selesnick, Zoe Leonard, Laurie Long, and Richard Zoller. This exhibition presented a combination of emerging and well-established artists that created fantasy photographs through role-playing and the use of alternate personas

2000

Photography in Human Experience, year 1

John Jacob and Sara Dassel, project managers

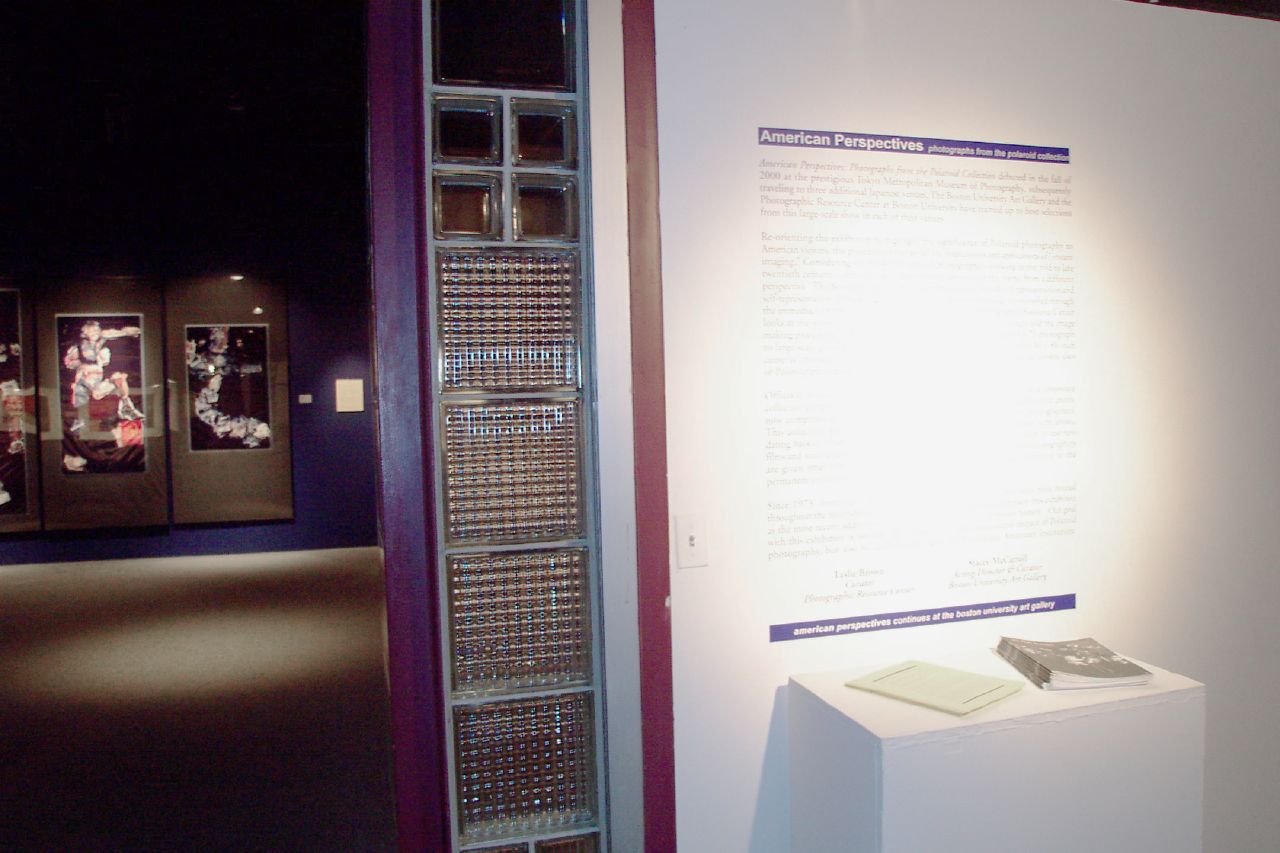

American Perspectives: Photographs from the Polaroid Collection

Michiko Kasahara, curator. Barbara Hitchcock and John Jacob, co-coordinators and authors for Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, shown at PRC in 2002

2001

Photography in Human Experience, year 2

Terrence Morash, Sara Dassel, and Leslie Brown, project managers

Voyages per(Formed): Photography and Travel in the Gilded Age

Alison Nordström, curator. Tourist photographs made before World War I with work by Carol Flax, Peter Goin, Abelardo Morell, and Lorie Novak

2002

there is no eye: Photographs by John Cohen

John Jacob, curator. There is no Eye was the first major retrospective exhibition of photographs by John Cohen, the musician who provided inspiration for the Grateful Dead song “Uncle John’s Band.” The exhibition of over 130 stunning black-and-white images made its debut at the PRC before travelling nationally. As co-founder of the band, the New Lost City Ramblers in 1958 and a regular writer for Sing Out Magazine, Cohen was central to the emergence of the urban folk revival of the 1960s. The sensitive portraits provided a virtual lesson in 1960s cultural history and included Alan Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Franz Kline, Red Grooms, Woodie Guthrie, Bill Monroe, the Stanley Brothers, Doc Watson, Roscoe Holcomb as well as an extremely young Bob Dylan

Photographs by Dennis Hopper: 1961-1967

Co-curator with Robert Seydel. This exhibition included images of artists, activists and celebrities, many of whom have since earned legendary status as cult heroes. Actor, director, and artist Dennis Hopper photographed during the sixties and created a visual record of “who’s who” with telling portraits of emerging stars.

Companion Exhibition:

Minefields: Bill Burke. The work of Minefields, pulled from Bill Burke’s book of collaged images, ephemera, newspaper clippings, letters and journal entries, created a personal, political and often terrifying narrative of Burke’s trips to Cambodia. Burke’s photographs presented the underlying threat and reality of human vulnerability operating on multiple levels.

Return and Exile: Sylvia Plachy’s Photographs from Central Europe and Susan Rubin Suleiman’s Budapest Diary

Rubin Suleiman and Sylvia Plachy were featured together in an exhibition that explored the experience of an exile returning to her native homeland. The two left Hungary in 1949 and 1956, respectively seeking personal and political freedom in the United States. Years later they both returned to Hungary, each recording the memories, emotions and thoughts connected with the country of their youth, Suleiman with words and Plachy with photographs.

Matthias Leupold: Fahnenappell & Gartenlaube

Fahnenappell (Flag Raising Ceremony) and Gartenlaube (Photographs for Devotees in Remembrance of an Illustrated Family Magazine) were two photographic series from Matthias Leupold, a contemporary artist from the former East Germany. With props and actors, he restaged the subjects of paintings and sculptures that were originally featured in the Third German Art Exhibition held in Dresden in 1953. He also recreated images from an illustrated magazine for women that revealed the visual rhetoric employed in photographs of women’s social activities.

Matthias Leupold: Fahnenappell

Die Gartenlaube, hardback edition, 1911

Facing Death: Portraits from Cambodia’s Killing Fields

Co-curator with Robert Seydel, in cooperation with The Archives Group. This was the U.S. premiere of 100 images of victims of Khmer Rouge prison, which documented and recorded the terror from 1975-1979. The portraits are a part of a little known archive of horror at the Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocide in Cambodia. Portions of the PRC-sponsored traveling exhibition showed at the Ansel Adams Center for Photography in San Francisco and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Facing Death was also published as a monograph by Twin Palm Publishers.

Extended Play: Between Rock and an Art Space

Extended Play was a festival of exhibitions and events that explored visual art work by musicians.

Extended Play included photographs, video, fashion design and works on paper by Willie Alexander, Laurie Anderson, Peter Blegvad, John Cohen, Kevin Coyne, Chris Cutler, Fred Frith, Kim Gordon, Mike Gordon, Tony Levin, Christian Marclay, Eric Meza, Lou Reed, Vernon Reid, Patti Smith, and Sandra Stark.

Companion Exhibitions:

The Velvet Years, 1965-67: Warhol’s Factory, Photographs by Stephen Shore

May 9 – July 6, 1997

Organized by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum in Cleveland, the photographs depicted scenes at Warhol’s factory from 1965 to 1967, a time when Warhol was emerging as a prominent visual artist and filmmaker. Among the regulars at the factory during those years was the band Velvet Underground, who Warhol promoted and showcased.

Velvet Rarities: From the Collection of Jay Reeg

May 9 – July 6, 1997

This exhibition presented a variety of objects and ephemera related to the Velvet Underground assembled by Massachusetts-based collector Jay Reeg. The small exhibition showed rare photographs, posters, album covers, and other materials pertaining to the band, and to their musical successors such as Willie Alexander and Patti Smith.

Picture and Sound: Music Photography by Kathy Chapman, Michael Greco, B.C. Kagan and Phil in Phlash

July 18 – August 17, 1997

In the 1970s, Boston was one of the country’s intense breeding grounds for punk and new wave music. This exhibition reunited four photographers who were critical in documenting that scene in four very different styles. The show included Kathy Chapman’s documents of the interior lives and living spaces of musicians and their audiences; Michael Grecco’s moody studio portraits, using elaborate props and complex lighting; B.C. Kagan’s backstage portraits, showing musicians in their working environment; and Phil in Plash’s photographs of live music, depicting the interaction of music and their fans. The exhibition presented new as well as older work by the artists, covering changes in the music industry from the mid 70s to the present.

Being There: Photographs by Billie Perry and Karen Whitford

May 9 – August 17, 1997

Presented simultaneously with Picture and Sound, this exhibition presented an Aerosmith family album, a look at the music industry from “inside the bus.” Perry and Whitford are married to Aerosmith guitarists Joe Perry and Brad Whitford, and photographically documented the private lives of their musical families for years. This first exhibition of their work together showed the intimacy of the group as they work and play together, and documents their interaction, as well as numerous other personages in the music world and entertainment industries.

Companion Exhibitions:

Two Times Intro:

Photographs by Michael Stipe, Drawings by Patti Smith, and Polaroid Prints by Oliver Ray

September 11 – October 23, 1998

The continuation of the Between a Rock and an Art Space theme featured drawings by Patti Smith and Polaroid prints by Oliver Ray as well as a visual diary of Stipe’s experience as a musician and practicing visual artist. Stipe’s photographs followed the lead singer and songwriter for the band R.E.M. and Patti Smith as they toured with Bob Dylan in 1995.

American Perspectives: Photographs from the Polaroid Collection

American Perspectives premiered in the US at two Boston, MA venues: the Photographic Resource Center and the Boston University Art Gallery. The show, consisting of more than 90 works by almost 50 American artists, was on display from November 22, 2002 through January 26, 2003.

American Perspectives returned to the US after a successful two-year run in Japan. It initially premiered in the fall of 2000, at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. In 2001, American Perspectives then traveled to Kyoto’s Museum EKI, appearing next at Takamatsu City Museum of Art, with its final show in Sapporo at the Museum of Contemporary Art.

American Perspectives was curated by Michiko Kasahara. Jacob and Barbara Hitchcock, director of Cultural Affairs at Polaroid and Curator of the Polaroid Collections, coordinated the exhibition in the US in cooperation with Noriko Fuku and Associates. Jacob and Hitchcock contributed essays to the catalogue and presented papers with Kasahara for an accompanying public program of the Tokyo Met.

American Perspectives: Photographs from the Polaroid Collection (open PDF / download PDF)

Photography in Human Experience

Photography in Human Experience was a multi-year, cross-disciplinary exhibition and education program series that evolved through the re-crafting of the PRC’s institutional mission. Its goal was to expand the PRC’s artistic mission by embracing a broad range of photographic and institutional practices, and to redefine its curatorial methodology by integrating diverse voices into the programming process. The program received broad support from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Institute of Museum and Library Services, and the Massachusetts Cultural Council. The program was conceived by PRC director John Jacob and former director of exhibitions Robert Seydel, and overseen by curators Sara Rosenfeld Dassel and Leslie Brown.

The Photography in Human Experience program was developed to explore the role of photography in shaping human knowledge and experience, and involved extensive collaboration between participating institutions and artists. Year-long thematic exhibitions of historical work in photography, drawn from archival sources, were augmented by rotating exhibitions of contemporary work related to the theme. While the historical exhibitions were organized by the PRC, a key component of the program required that exhibitions of contemporary work be guest curated by commissioned artists, and supported by teams of scholars and experts. The series took two years of planning followed by two years of public exhibitions and programs. A third year of exhibitions was planned but abandoned after Jacob left the PRC.

In its first year, in cooperation with the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, the program explored turn-of-the-century and contemporary conceptions of photography’s relationship to four categories of human experience: Family, Media, Technology, and Spirituality.

• Fractured Mirrors, Broken Windows: In the Marketplace of Private Life

Curated by Deborah Bright. This exhibition offered an incisive and probing examination of the traditional idea of “family” and personal affiliations. The work presented aimed to direct the viewer beyond superficial notions, and drive them to consider more inclusive meanings of these concepts. Works by The Art of Change, Kaucyila Brooke, Mohini Chandra, Carole Conde and Karl Beveridge, Sunil Gupta, Yoshio Itagaki, and Ho Tam, and a selection of zines from the collection of Stephen Duncombe

• Gathering Information: Photography & the Media

Curated by Susan Erony. This exhibition explored photography’s relationship with the media. Erony sought to re-create the experience of “information overload” by asking eleven artists to come up with work that would “portray their reactions to disturbing media imagery, and, how, in the face of such imagery, they maintain hope.” Works by Lee Barron, Nadine Boughton, Greg Hitchcock, Allison Hunter, Jay Jaroslav and Shep Abbott, Ruth Liberman, Erika Marquardt, Ellen Rothenberg, Rochelle Rubinstein, and Peter Scott

• Particle Accelerators: Intersections of Photography, Science, & Technology

Curated by Jane D. Marsching. This exhibition looked at the efforts and ideas of contemporary artists working within and across the disciplines of science, technology and art. Works by Jordan Crandall, Susan Derges, Laura Emrick, Fakeshop, Joan Fontcuberta, Ken Goldberg, Blainey Kern, Tina LaPorta, David Nyzio, Gary Schneider, Sterck & Rozo, Todd Watts, Wenyon & Gamble, and Gail Wight. Particle Accelerators exhibitions archive page

• Representing the Intangible

Curated by John O’Reilly. O’Reilly provided a personal reflection on a photograph’s ability to capture and convey experiences. He created groupings and sequences of photographs that served to narrate ideas such as morality, awe, the passage of time, mystery and ephemeral beauty. Works by Robert Adams, Dieter Appelt, Karl Baden, James Casbere, John Coplans, Tim Davis, Jaques Henri Lartrigue, Helen Levitt, O. Winston Link, Paul McDonough, Duane Michals, Abelardo Morell, Mark Morrisroe, James Nachtwey, Tod Papageorge, Thomas Roma, Seth Rubin, August Sander, Toshio Shibata, and Garry Winogrand

In its second year, in cooperation with Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum, the program explored historical and contemporary photography from four thematic categories: Animals, Consumption and the Natural World, Indexing and Cataloguing, and Rethinking the Landscape.

• Significant Other: The Human Presence in Contemporary Animal Imagery

Curated by Sara Rosenfeld Dassel. This exhibition reflected on the human presence, whether intentional or not, in contemporary animal imagery. Works by James Balog, Catherine Chalmers, Linda Darling, Per Manning, Frank Noelker, Victor Schrager, Richard Silberman, and Kunié Sugiura

• sprawl

Curated by Henry Horenstein and Thomas Gearty. This exhibition explored the idea of “sprawl.” It included works dealing with: density of development; the effect of parceling on open land, strip development along highways at the expense of decaying downtowns, car culture, excessive road development and communities that are reliant upon automobiles, mall culture, and a social aspect of living in a sprawl environment. Works by Alex MacLean, Adolpho Barandiaran, Bill Owens, Steve Smith, Peter Garfield, Mark Klett, and Allan Penn

• Strange Attractor: In the Orbit of the Artist

Curated by Rosamond Purcell. Purcell explored the inexplicable forces of attraction, such as that described by the Chaos Theory term “ strange attractor.” This exhibition explored the different forces of attraction that drew artists toward their respective obsessions. Purcell suggested new connections between very different bodies of work selected for the exhibition. Works by Mark Sloan, Linda Connor, Edward Ranney, Ken Brecher and Piers Adam Brecher, Mary Jo McConnell, Crystal Woodward, Catherine Wetzel, Elizabeth King, and Max Auilera-Hellweg

• Rocks & Trees

Curated by David Armstrong. Works by 33 contemporary landscape photographers. Armstrong addressed the basic issue of the factual photography through a selection of images elaborating on themes of art and nature, naturalism, and constructed landscape.

The conversation with Alison Nordström, for her exhibition Voyages per(Formed): Photography and Travel in the Gilded Age to travel to the PRC, was initiated by Jacob before his departure. Though not curated by an artist, it used a discursive pairing of archival and contemporary photographs comparable to that of PHE. Drawn from the collections of the Boston Public Library, private collections, and the Southeast Museum of Photography, it focused on albums selected from a set of twenty-six made in the 1890s by the Tupper family of Brooklyn. Four contemporary artists—Carol Flax, Peter Goin, Abelardo Morell, and Lorie Novak—were commissioned to produce new work on the subject of nineteenth century travel.

The exhibition Concerning the Spiritual in Photography was initiated as a PHE project by Jacob. Before leaving the PRC, he did extensive research in the Arthur Conan Doyle collections at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas, Austin. Jacob would continue his research on spirit photography in numerous other projects, post-PRC. The project was completed outside the PHE program by PRC curator Leslie Brown, in 2004.

John Cohen: there is no eye

There is no Eye was the first major retrospective exhibition of photographs by John Cohen, the musician who provided inspiration for the Grateful Dead song “Uncle John’s Band.” The exhibition of over 130 stunning black-and-white images made its debut at the PRC before travelling nationally. As co-founder of the band, the New Lost City Ramblers in 1958 and a regular writer for Sing Out Magazine, Cohen was central to the emergence of the urban folk revival of the 1960s. The sensitive portraits provided a virtual lesson in 1960s cultural history and included Alan Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Franz Kline, Red Grooms, Woodie Guthrie, Bill Monroe, the Stanley Brothers, Doc Watson, Roscoe Holcomb as well as an extremely young Bob Dylan.

Postscript, some words on the occasion of a memorial

John P. Jacob, New York City, 2011

Robert and I worked together at the Photographic Resource Center, in Boston, during the 1990s. I had worked as an independent curator before that, and Robert was fresh out of RISD, but neither of us were remotely prepared for the difficulties we would encounter there. The organization was in deep financial trouble, and less than a year after we arrived the director quit, followed by other staff and Board members. Robert and I were the last two left standing, and when the time came to decide whether we should stay or go, nobody would have faulted us for running. But the situation seemed too interesting to run from; like an unanticipated gift, but with a riddle attached. The riddle was how two guys who couldn’t even balance their own checkbooks were going to pay off nearly $1M debt. The gift was a gallery to play in if we succeeded. And that’s exactly how we approached the riddle: by playing. We divided up responsibilities by shooting “rock, paper, scissors,” and of course Robert won all the interesting jobs.

Our first decision was to bring in a celebrity, to make a public statement that the PRC was open for business. Robert and I had different ideas about “celebrity,” but finally we agreed on Dennis Hopper, and Robert disappeared into his office for a few days. When he emerged again, Robert was wearing that tiny smile of modest self-pleasure. He had spoken to “Dennis,” who had agreed not only to an exhibition, but also to three days of personal appearances with us. It was the first of many small miracles. But of all the things we did together during that time, what we enjoyed most was installations. We’d close the galleries, and Robert would bring in his boom-box. He was the absolute boss of music, and he considered it no less important to convince me of the merits of some newly discovered musician than to hang the incoming show. Against this background of music, Robert would begin by placing an artwork against the wall like the first move in a game of chess, then I’d place a second one somewhere else. Gradually, relationships between pictures would be established, challenged, demolished, and restored. A narrative would emerge, which we would follow as far as it could take us. We gave the process two full weeks, sometimes working around the clock and breakfasting at the IHoP in Kenmore Square. If we finished with a few hours left before the opening, we’d spend that time at The Rat, recounting the many erroneous paths we’d taken along the way to success.

Many months later, after it became clear that the PRC would survive, Robert and I made several road trips, and during the long drives we talked and talked and talked. Out of those conversations emerged the frameworks for a completely new kind of institution. It would involve artists as curators, match them with teams of scholars working across academic disciplines, and draw extensively from archival sources to contextualize contemporary artwork. Transforming this idea into a reality was an enormous undertaking on top of our day-to-day work, and the exertion of it gradually took a toll on both of us. Robert complained that he had no time for his own artwork, and when he was offered a year-long position at the University of Connecticut, he decided to take it. I continued to work towards our plan, and when the “Photography in Human Experience” program launched, two years later, Robert came for the opening. We spent the better part of it hiding out in my office, sipping whiskey and talking deep into the night, just like old times.

As his year in Connecticut drew to an end, Robert visited me to talk about his future. He wanted to continue teaching, he said, but not at Storrs, and preferably somewhere where he could enjoy the security of tenure. He was leaning toward New Mexico, where he’d be closer to his sister and her family, but there was an opening at a school named Hampshire; what did I know about it? Robert was reluctant to waste time interviewing with a school that didn’t offer tenure, but I urged him to look at Hampshire more carefully, and to consider the community of a college as the true key to any long-term security there. Over the years to come, I was pleased to see my advice proven right. Robert found his voice as a teacher at Hampshire, and its community provided him with the support and stability to pursue his art work; eventually the two activities became intertwined as one. It was a good match, and whenever I saw or spoke to Robert after that he seemed clear and happy.

I left Boston and the PRC on New Year’s day, Y2K, and for a time after that Robert and I fell in and out of touch. I suppose that I took it for granted that his gentle voice would always be present. After all, so much of my life had been shaped by the experiences we shared, and so much of my work by the strategies we developed to deal with those experiences. We encountered every problem with a conversation, and every failure as an opportunity. But Robert and I also experienced compromise, and exhaustion with the ideas we loved. After we had succeeded in saving the PRC, when we were no longer playing in the gallery but doing the serious work of fundraising and program development, we both lost interest in institution building. Robert left the PRC because he wanted to play again, and he found the freedom to do that at Hampshire. For my part, the rich vein of ideas that Robert and I explored together has continued to guide me in my work and in the world. Over the passing years, I have carried on this conversation with Robert, always grateful to have had his complete confidence from the outset. Although I feel his loss cruelly, my conversation with Robert remains very much alive; vital and ongoing.

Robert, you brought so much sweetness to my life. Thank you, Robert, for the gift of our much too brief time together.

Robert E. Seydel Memorial, Hampshire College, 2011