Maybe at this point a short explanation is needed why in the GDR all types of photography, even photojournalism, could be thought of as an artistic achievement. -- Wolfgang Kil, 1993

Foreword

Karla Sachse, Berlin, April 1993

At first glance, the following texts differ too widely to give us coherent information about the past existence of art photography in the German Democratic Republic. However, it seems no coincidence that out of all the different possible and considered perspectives these three come together at this time and under these circumstances.

In the past years Wolfgang Kil has attempted several times to get an overview of and to penetrate analytically the connections between developments in the social reality (and surreality) of the GDR and photography. It may be for this reason that he accepts the desire to strike a balance once more unreluctantly, even though he is one of only a few people who have long placed the specific internal developments in an international context – modern as well as post-modern. And he less than ever hides the fact that, in doing this, he proceeds from a position for which a certain moral claim and human interest remain important. Kil has returned to his original field of activity – architecture – which was closed to him during the existence of the GDR. And even though this for now latest text about photography was written for a specific group of photographers it nevertheless depicts a background for very diverse forms of artistic articulation. By striking a general balance he also avoids name-dropping which a number of art dealers seemingly use only to gauge the usefulness of single photographers for the western art market or to use entire branches of artistic evolution to “prove” trends in East German photography or “astonishing” parallels with Western conceptions [of art].If a few photos in that text are classified (not by Kil himself, by the way) then they, too, are abused as pieces of evidence. Accordingly, they should be viewed with caution – and above all they should make you curious.

The photo historian Andreas Krase refuses the common demand to press the complex development processes of a photographic oeuvre into conclusive terms and relations in a different way. 1In her German original Karla Sachse uses the word “kurz-schluessig”, which she composed from the words “kurz” (meaning short) and “schluessig (meaning conclusive). It could therefore be interpreted as “drawing a fast conclusion” ( one that does not bear closer scrutiny). However, there is also a noun “der Kurzschluss” which means “short-circuit”. This way of reading the original “kurz-schluessig” reinforces the idea of wrong connections. He expects the distant (as well as the not-so-distant) reader to follow the detailed description of a single persons life. It is that of a woman who, with her photography, was one of the first [people] to develop and retain her artistic independence against all odds in the Closed Society – Evelyn Richter. He does this with the understanding that with it he also touches a part of his own history as well as part of general history. A part that is all too easily lost in words. At the same time it becomes apparent that the innermost motives for a certain artistic concept can not be explained solely from the characteristics of the social situation in the GDR nor from the friction with ideologic pressures. And last but not least it is a pladoyer for an artistic attitude which in the “New Time” – notwithstanding the honors presently bestowed upon Evelyn Richter – will probably very soon be of historical interest only.

Even if Susanne Klengel does not direct her “view from without” specifically at photography but tries to characterize with her perceptions just that view some important characteristics surface. Interest in the seemingly closed chapter GDR photography is specifically tinged by those characteristics, both from “within” as well as “from without”. From “within” this interest has been quite desired or even met with feverish expectation. But enthusiasm for this ambivalent exoticism, the ethnologic point if view [of the interest] as well as the yearning search for the fragments of a lost utopia are painful because they ultimately and matter-of-factly assume the modern Western world as the only standard. 2Karla Sachse uses “selbst-verstaendlich”. The word “selbstverstaendlich” means “of course”, “as a matter of fact”. “Das Selbstverstaendnis” means “ones conception of oneself”. And the pain is twofold because most East Germans thought that the Western orientation had long been internalized. But it may be that a new beginning will grow exactly from this mutual insecurity in orientation; an interest that accepts the “other” without constantly having to subordinate it to one`s own values. And this might be helpful in our so vehemently diverging world…

To convey an idea of the scope of photography in East Germany before 1989 the following three more aspects need to be mentioned:

The growing (socially critical) attitude did not remain limited to independent art photography. Even the most conformist press photographers were constantly reminded of “criticism” in their pictures by the mechanisms of censorship and they ended up creating that twofold readability – whether they wanted or not. On the one hand the very broad (and nowadays hardly mentioned) area of amateur photography had been made into an instrument – dilettantism “for the good of the people”. On the other hand a few very special and stringent documentarists, whose conceptual ideas have been examined very little, grew out of this publicly funded area. And some of the most radical photo artists (e.g. Florschuetz, Leupold) could never produce any kind of diploma for their work..

And finally: in the discussion of straight photography usually those artistic concepts are not taken into consideration at all which use photographs as material, make them into photo montages, with or without text… At this time the following texts can only give a first impression of the photography of a “historical space” but it is hoped that it will stir an interest in this topic.

Out of Control: Photography from East Germany

Karla Sachse

Foreword

Wolfgang Kil

Ostkreuz: An Origin Stopped in Time

Ostkreuz Portfolio

Sibylle Bergemann

Harald Hauswald

Ute Mahler

Jenz Rotzsch

Harf Zimmerman

Andreas Krase

The Work of Evelyn Richter

Evelyn Richter Portfolio

Susanne Klengel

The Near Distance — “Cultural Otherness” in the Two Germanies

Matthias Leupold Portfolio

John P. Jacob

Postscript

Translations by Chris Egger, 1993

Ostkreuz: An Origin Stopped in Time

Wolfgang Kil, Berlin 1993

“It is as if someone had pushed open the windows…” With these words Stephan Heym began his speech in front of 700.000 demonstrators on Alexander Square in Berlin on November 4, 1989. Still unbelieving, yet full of hope, the old poet greeted the fresh [political] breeze that had blown into the land of spiritual, economic and political stagnation so unexpectedly. And he could not foresee (nobody could foresee) that this wind should be only a prelude to a very powerful storm: a storm that, a mere five days later, was going to completely destroy the state, which had been ruined and become unrulable.

When, after the windows, the doors flew open, too, in that unforgettable Thursday night, the day of reckoning had come. Ever since then it is appropriate to speak of the German Democratic Republic as something of the past. November 9 sealed the end and the fiasco of a historic project. What remains are textbooks full of political insights and millions of lives that bear traces of a peculiar cultural experience. Everything in this landscape will change; cars and billboards, towns and villages, the water in the rivers and the air we breathe, probably even the expressions on peoples faces. Just one thing should not be expected for a while – origins.

Outside its borders much has been said and judged about the role that art and artists played in the social environment of the GDR. Depending on political appropriateness the affirmative, even propagandistic character of the “state art” was lamented, the mediocrity of a “non-avant-garde province”smiled at or the rebellious spirit of the non-conformists as well as the chic of an exotic scene celebrated. All of these points of view were justifiable though none – in the scheme of things – was just. Because where does it exist -THE art or THE artist?

Photography is no exception. It, too, has never existed as a GDR-specific version. If there is supposed to have been a difference at all we have to search for it behind the pictures or around them; a very peculiar moral ambition of the photographers and a very direct, almost hungry interest of a broad public in their products. And mutual respect, which in m any other places has long been considered naive and gullible; but here it still worked, this missionary hope. Almost to the end wholesome skepticism was not able to undermine this unquestioning trust in pictures: photography must show us what exists. Stopped time.

The work of the photographers at the same time suffered and profited under the hair-raising equilibrium disorders and behavioral problems in the “Closed Society of the GDR”. As long as the mass media, completely forced into line, reproduced illusionary worlds bridled with propaganda, as long as they put a taboo on every serious social conflict a nd thereby tried to ban reality from public consciousness, the desperate role of an ersatz-public fell to the art media. Writers, film and theater directors, rock musicians as well as photographers took on that troublesome part of reality which was not al lowed to exist in the press or on TV. Accordingly, public interest in the messages of those artists, who dealt with everyday experiences, was strong and at times even enthusiastic. It was directly proportional to the lack of interest with which the offici al propaganda was met. What was in demand where pictures of real life [In German: “Abbilder”], not wishful projections [“Wunschbilder”]. This provided the artists with a lot of attention and the motivating feeling to be needed and to have responsibility. Be it in Dresden, where the audience of the mammoth art shows was counted by the hundreds of thousands or (for example) in Berlin, where a small gallery tucked away in a small side street attracted thirteen thousand visitors in six weeks (during a spectacular one-person show of a young woman photographer) the situation was the same: constantly sold out theaters, notoriously out of print books and endless lines outside exhibitio n doors. We can not blame the artists for the fact that the often over-stressed and self-flattering aura of an art-friendly GDR or of a reading-culture GDR can actually be attributed to a considerable degree to a deficit in non-art areas. They simply rea cted to the unsatisfied desire for public communication [“Selbstverstaendigung”] and it greatly influenced their conception of art.

Maybe at this point a short explanation is needed why in the GDR all types of photography, even photojournalism, could be thought of as an artistic achievement. On the one hand the number of independent photographers who, with their work, would have nothing to do with the censorship of the official media, had grown in the late 70-s to such proportions that the “Verband bildender Kuenstler” [Association of Plastic Artists] formed a special Study Group Photography. This opened considerable possibilities for development. Even in this artists association every photographer still had to secure his/her own material existence – in any way possible. But at least with the status of “artist” there were possibilities to participate in extensive cultural activities (e.g. grants and stipends, study visits, exhibitions,…). On the other hand the independent photographers became quite distanced from their original bond with the printed media (i.e. the thinking in categories of usability), due to their complete self-determination and the fact that they worked basically without instructions. This conception of them selves has in fact brought them closer to the concept of artistic self-expression as opposed to merely transmitting news. The mass media being totally inaccessible to them, even a simple photo documentary could receive the importance of a purely personal message of the photographer – or at least it was common to interpret it as such in exhibitions.

The development of photography in the GDR has been defined largely by the narrative picture until the late 80-s. Photographers with a background shaped by journalism had ventured out to work independently and they were the first ones to stake out that new territory of independent activities which were then called artistic. They became the role models, set the standards for a long time and directed the attention of those coming after them to psychology, to stories and history. For themselves they claimed t he “human interest”, since the irrational, the lies of a perfect world and the cynical were so obviously in the services of “the other side”. Pausing for a moment, pensiveness, looking as a way of reading, the attempt to get the feel of a certain atmosphe re, metaphors for forelornness or yearning – these were the first signs of resistance with which the artists tried to fight off a propagandistic takeover of their moral integrity. Observations, not claims! [“Beobachten statt behaupten!”]

The road into the uncertainties of an existence mostly without instructions was taken freely and set free certain forces that radicalized especially some of the works of the younger artists who followed and that made them much more outspoken. They took on that rather miserable reality, dissecting it; and what they brought to the surface was shocking and cuttingly sarcastic. Long since there existed two picture-worlds of the so called real socialism and those living in it much appreciated the efforts of those independent photographers who had to rely almost entirely on galleries and art exhibitions as a public forum.

In this way photography in the GDR developed under the conditions of a pressure cabin; little by little, easily manageable, and highly condensed. Contacts in professional circles were close, an intimacy that bordered on confinement, with all its advantages and disadvantages. Even when the mental walls became more permeable and books, exhibits as well as the possibility to travel put the national scene more in touch with trends in international photography most of the photographers in the GDR remained cooly at a distance to the fads and vanities that were so rampant worldwide. The experiences of their own lives remained more important, the moral of voluntary involvement seemed interminable. Success in distant places, as far as it finally occurred, was reason for joy but compared to the unescapable reality of every day life it remained “outside”. Here, those who set out to start their careers very soon found themselves outside, literally as well as figuratively. The GDR could never bear more than local greatness. The reason for this might have been the system: without a market there are no top ten lists and no stars. But plenty of insider tips and a mutual attentiveness, a willingness to pay attention to details. And a public to whom one liked to present one’s pictures for discussion because it was competent where reality was concerned and inevitably shared in the artists’ frustration, mourning and rage. Also the seemingly never faltering believe in the feasibility of the maxim “I want to be active in this world” which, at some time or another, every school kid learned as part of a declaration by Kaethe Kollwitz. In even the most defiant defensive reaction and in the harshest refusal of the existing situation there could still be found a little rest of this believe. And the secret of this peculiar tenacity: affection.

Now the windows and doors are open, wide open. The microclimate in the glasshouse GDR that had been balanced over decades in a painstaking process suddenly lost its equilibrium. The society of the GDR, which has been thrown into the whirl of world markets unprepared, does not only have to restructure its economic basis. It also has to cope with the process of redefining its intellectual fundament. Within a few weeks after the fall of the media monopoly (held by the Socialist Unity Party of Germany) a diverse process of opinion forming through the mass-media had developed. The artists, who up until then had played the role of an ersatz public, were relieved of their function from one day to the next. Only very few of them were at all able to influence the explosion of new problems and questions that they and their audience have been besieged with ev er since. All of a sudden the traditional conventions and symbols, without which communication between artists and their audience is impossible, lost all their meaning. The usual feedback to ones own work that could always be personally felt, now failed to materialize. What happened here is nothing less than the total loss of all cultural points of reference. Due to the economic collapse, work relations as well as the system of commissions and professional associations that had been stable up until now dissolved. And this, also, had dire consequences for the productivity of all artists. But in the long run one thing will be crucial for the survival of the art workers who have been released into the market: it is how well they will be able to cope with the transition into an entirely different value system, from a leisurely and pensive civilization into a fast paced and innovation crazed one. One question that, inevitably, will have to be faced is the one about the meaning of all past endeavors. The new situation can not be had at a lower price than that.

Out of Control: Photography from East Germany

Karla Sachse

Foreword

Wolfgang Kil

Ostkreuz: An Origin Stopped in Time

Ostkreuz Portfolio

Sibylle Bergemann

Harald Hauswald

Ute Mahler

Jenz Rotzsch

Harf Zimmerman

Andreas Krase

The Work of Evelyn Richter

Evelyn Richter Portfolio

Susanne Klengel

The Near Distance — “Cultural Otherness” in the Two Germanies

Matthias Leupold Portfolio

John P. Jacob

Postscript

Translations by Chris Egger, 1993

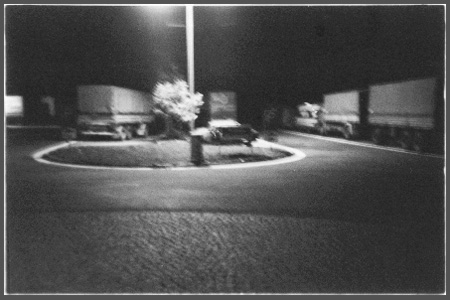

Ostkreuz Portfolio

Sibylle Bergemann

Harald Hauswald

Ute Mahler

Jenz Rotzsch

Harf Zimmerman

Out of Control: Photography from East Germany

Karla Sachse

Foreword

Wolfgang Kil

Ostkreuz: An Origin Stopped in Time

Ostkreuz Portfolio

Sibylle Bergemann

Harald Hauswald

Ute Mahler

Jenz Rotzsch

Harf Zimmerman

Andreas Krase

The Work of Evelyn Richter

Evelyn Richter Portfolio

Susanne Klengel

The Near Distance — “Cultural Otherness” in the Two Germanies

Matthias Leupold Portfolio

John P. Jacob

Postscript

Translations by Chris Egger, 1993

The Photographer Evelyn Richter: The work of one of the “founding generation” of photography in the GDR

Andreas Krase, Berlin 1993

Introduction: Documentation, Vision, Projection

In the past years several attempts have been made to describe the phenomenon “Photography in the GDR”. Especially after the end of the GDR it has become apparent that there has been a phase of intensive developments and processes. This phase began in the late 70-s and led to the acceptance of photography as a medium of artistic interpretation that could persist even in a climate of official resistance.

Because the public was so sealed off there was, in the population, a real need for information and discussion that could be satisfied, among other things, with photographs. And on the other hand this caused a very distinctive form of moral self-conception [Selbstverstaendnis] with the photographers. But this was not the only peculiarity of the photo scene in the GDR.

“Photography in the GDR” also always includes the fact that certain decisions made by artists and photographers could cause the departure from that “photo-scene” – the forced or deliberate emigration from the GDR – that people and their artistic aspirations were formed by very specific circumstances and conditions.

For this reason we must not only talk about that closed system GDR inside of which this photography developed. We must also consider the ruptures and gaps, the difficulties in orientation of those who left and the feeling of powerlessness and of being left over that came to haunt those who stayed behind after each of several “waves of emigration” and m ade them question the meaning of all their endeavors.

Seen from without only those works count, of course, that are perceived as distinctive and that are rated according to their spiritual and sensual radiance. Seen from this angle it should be noted that art photography in the GDR essentially consisted of three strains that can partially be assigned to certain age groups of photographers.

Strongly simplified we can say that there was a dominance of socially active Live-photography that in the beginning had to gain acceptance against strong resistance from the official cultural-political establishment and that was pursued by only very few photographers. The missionary and emotional power of those pictures of reality constituted a basic value that was not questioned. Because of this it was possible that photography and some photographers could indeed become a kind of moral institution and found a tradition that rooted in the documentary abilities of photography.

During the late 70s a new generation of photographers that was generally quite critical of the realities in the GDR started to consciously use photography as a means of subjective expression and they began developing a personal vocabulary of forms. Reality here became a material that served as a model for photographic vision. It became the stuff of which dreams as well as nightmares could be made.

Yet another method was used by those photographers who not only viewed reality all around them in a critical light, but who for the most part rejected it. For this reason they began to stage their pictures in front of the camera, they began to create reality before their cameras. In this context photography was but one medium among many others to choose from. The artists often related their projections to multi-media happenings and performances that sometimes provoked absurd overreactions by the state powers.

Those last developments later attracted the strongest attentions and, like the second strain of developments, soon became quite well-known through exhibitions.

Much less attention has been given to those approaches that were rooted in documentation and that were viewed as less spectacular or as more traditional after the end of the GDR. But without the photographers of that “founding generation” we can not fully understand the entire development since their work created important points of reference for the processes that followed – not to mention the direct and mutual effects on politics and cultural politics in the GDR.

One reference to the “founding generation” was expressed in the total rejection of a photography in the tradition of the “human interest”: the radical change of values in the new generation, their often playful cynicism and the rejection of out-dated social, utopian dreams could not co-exist with a documentary or “realistic” photography.

It is easy to name the members of that “founding generation” since there are only two photographers: Evelyn Richter from Leipzig and Arno Fischer from Berlin. The stories of their lives, though specific, can nonetheless be considered paradigms since they contain not only the fate of the post-war generation in East Germany but also a part of modern history that certainly befits a discussion of “GDR Photography”. Both acted as teachers at the “Hochschule fuer Grafik und Buchkunst” [College for Graphic and Book Arts] in Leipzig and through the instruction of photo students they exerted an additional influence -a fact that can not be overestimated.

Though the following text is about Evelyn Richter’s life and work it is hoped that this may serve as an introduction to the topic “Photography in the GDR” and that further contributions will help us in gaining a better, more coherent knowledge.

Evelyn Richter. Notes on her life and work.

“Whereas the avant-garde has been searching for a new visual language to expand our perceptions I see the potential of realistic photography in increasing, with its media-specific language, tolerance and openness through knowledge and in making them, through exact seeing, more sensitive to each other as well as to the perception of all of life.” 1

Emotionality, human knowledge and history combine in Evelyn Richter’s work in an unmistakable way. Her activities as a photographer are inseparable from the circumstances of her time which, for her as for most people of her generation, were conditioned by the material, political and cultural consequences of WWII in East Germany.

Paradoxically, the only generation that can properly be called a GDR generation is the one that reached adulthood just as the war was over and that began leading their own lives in devastated post-war Germany: the entire span of their professional lives fell between the years 1945-89. And they all, from one position or another, shared in the fate of the GDR -its utopian ideas, its constraints and excesses. The opening of the border in 1989 came too late for the people of this generation to catch up with the opportunities they had missed. But with the end of the GDR disappeared an essential cause of friction that had worn down so many and with which many had made their peace.

This is true for Evelyn Richter, too. Her photographs developed in that field of tensions of the circumstances around her: her cultural frame of reference, however, was always European Culture. Her specific determination as well as her passionate readiness to assert her artistic concepts are shaped by her twofold identity as a photographer and as a woman, both in a highly subjective as well as an objective-inevitable manner.

Evelyn Richter was born in 1930 in a town called Bautzen in Saxony and grew up in a well-to-do family that was open-minded about arts. On her father’s side her family had been living in the area for generations. Early-on she developed a relation to a tradition that had grown organically and was culturally conscious. This shaped her later life and, with its shaping of basic values, foreshadowed future conflicts. She attended a convent school that her parents had carefully chosen because of its distance to Nazi education and then later, until the end of the war as well as during the upheaval that followed, Unified Comprehensive School [Oberschule].

The end of the war brought the entrepreneurial family Richter the loss of house and home and complete expropriation of all their land. But at least it also brought the release of their oldest son from a POW camp. Ever since, though, there also existed for Evelyn Richter the stigma of middle class and this influenced all of her life’s decisions in many ways.

There was, first of all, this completely new perspective of having to connect her own life with an economically independent existence – an effort that grew to an unconditional desire especially because of the many hindrances and exclusions as well as her inability to internalize rational demands to earn a living. But even so the “art world” increasingly became the center of her life. In her parents’ home these developments were observed with goodwill and worry: her father urged her to choose a practical profession. Finally, the young woman left for Dresden to look for a training opportunity in the a rts and crafts.

The big city promised an escape from provincial confinement. But to a young woman with an interest in art Dresden, in its tragic state of total destruction by the war, had nothing to offer in terms of real possibilities for education. A coincidence led Evelyn Richter to a Dresden architect who was working on the preservation of historic monuments. In the house of Dr. Karl Bellmann and in the studio of his son-in-law Pan Walther she made her first, momentous contact with photography.

“I got there, I saw the pictures, they were pictorial things, in old frames, deep, velvety tones – I was fascinated. What I saw there was pure art photography, Dresden tradition. I saw this, had a conversation with him {Pan Walther.[Krase]} and I told him that I wanted to be a photographer. In THAT moment I made the decision.” 2 At that point, it was in the year 1948, Evelyn Richter quit school and started her education as a photographer. Pan Walther (1921-1987), whose self-conception [Selbstverstaendnis] as a photographer came out of the tradition of German photographers Hugo Erfurth and Franz Fiedler, represented in those days the continuation of a conservative aesthetic in photography.

Pan Walther taught his students classical composition and the rules of a photographic use of light. He imparted to her the conviction that a photograph is not just a pure copy of something but mainly a creative product. However, there were no further stimuli as far as contemporary photography was concerned. Important documentary achievements – e.g. the deeply distressing reports by Richard Peter sr. about the destruction of Dresden – were taken note of respectfully but in a reserved manner: this, as well as all photojournalism, was not art. A different story was the Dresden painter/photographer Edmund Kesting (1892-1970) whose multiple exposures and sandwiched montages later prompted Evelyn Richter to do some experimenting on her own.

Much more important was the extensive circle of friends of the families Bellmann and Walther: the woman photographer Grete Back (1878-1965) and the photographer Franz Fiedler (1885-1956) who could, due to their age, authentically relate the experiences of pictorial photography gave lectures every now and then in art photographic techniques.

The cultural atmosphere of those years, according to Evelyn Richter’s memories, was dominated by a sense of renewal and cultural opening. The deficit of information from without and the exodus of the artistic avant-garde during Nazi dictatorship had created a great desire to catch up spiritually, a kind of mental hunger for experiences for which every thing even remotely resembling normalcy became an event. But the political and economic formation of the state of East Germany did not stop for the artists of the banks of the river Loschwitz. The circle of customers of traditionally educated middle cla ss people who demanded art-photographic representation disappeared more and more. Very soon Pan Walther quit his studio business and followed his wife to West Germany. In 1952 Evelyn Richter finished her education on her own and worked as a photographer at the Technical University of Dresden. In 1953 she applied to study photography at the College for Graphic and Book Arts in Leipzig, up until 1989 the only art college with a degree program in photography in the GDR.

But the head of the photo department, the photographer Johannes Widmann (1904) who specialized in architectural photography, soon turned out to be the exact opposite of the wishes projected onto him, and so did the entire program.

The short phase of relative detente that followed Stalin’s death and the violent political upheavals in the year 1953 had only little effect on the college. Under the constraints of the dogma of realism Evelyn Richter experienced an atmosphere of intolerance and stylistic uptightness in the fine arts. And even though some lasting friendships grew as well the climate of everyday relations condensed to silence and depression. And this depression is expressed, among other things, in the portraits of her classmates. By and large the program followed completely out-dated patterns. The demanded orientation on 19th century history painting and genre painting and its ideologized imitation in Soviet art lead to absurd excesses: in the school basement, where into the post-war era high-tech printing studios had been located, the students photographed tableaux vivants after literary sources. This loss of [a connection to] reality hit Evelyn Richter in many respects hard and she came to see the art college increasingly as an “obscure institute”. Her attempts at developing observational photography in the sense of Live-photography were hardly taken note of at all. When finally attending lectures at other colleges in Leipzig became cause for public reprimands (e.g. the audience of the well-known German scholar Hans Mayer or applause in pu blic concerts of the latest music) and when attendance was strictly enforced, Evelyn Richter was no longer willing to be part of the college.

Moreover, Evelyn Richter, who would not deny her social origins nor her relation to traditional culture, got the small stipend which she was at best able to receive as a “middle class intellectual” terminated. Financially, her departure from the college was at first cushioned by an assignment that she had received from the state factory “Fotochemische Werke Berlin”, a former Kodak factory, while still a student. The occasion was the testing of a highly sensitive film (DIN 24) that had been introduced in the mid 50s and that opened up totally new dimension s in the representation of events and for live documentation. Evelyn Richter photographed in various theaters in Berlin and in the theater in Gera. Her attempt to become a permanent employee in Berlin and to establish herself there, with one eye on the West, was unsuccessful.

Even though in terms of content and style she moved towards the themes she was interested in she was still living between two extremes emotionally and spiritually. On the one hand her family’s expropriation still weighed heavily on her mind. On the other hand she was very aware of the fact that she was neither brought up to lead a practical existence nor did she have an innate ability for it. The impression that she got on several trips to West Germany convinced her that it would be difficult for her to integrate her personal interests and her desire to assert herself in either system.

Evelyn Richter decided to stay in the GDR, among other reasons because here the cost of living was markedly lower and because the border between the two German states was basically still permeable enough to allow travelling. Connected to this attitude of wait-and-see was the hope that the political system, which in its most basic statements promised a more just social order, was able to change. But that hope ultimately turned out to be an illusion. In the following years and up until the beginning of the 60-s Evelyn Richter exhausted all the possibilities of movement that were available in her specif ic situation. In the fall of 1955 she was able to see the exhibit “The Family of Man” in West Berlin and the impressions that she got of contemporary Western photography had a lasting effect on her. Magazines of the publication “Magnum” or the ideas of “subjective photography” of Otto Steinerts from Essen acted as catalysts in the process of artistic orientation especially because of their exquisite singularity.

Evelyn Richter noticed Henri Cartier-Bresson, the photographs of August Sander or Dorothea Lange a little later, after she had already developed some important positions by herself. The determining stimulus came from seemingly very ill-suited surroundings. In 1956 she won first prize in a juried exhibition for the World Youth Festival in Moscow. Her photograph showed an African dancer in the light of a camera flash and was interpreted by the jurors as “a symbol for the fight for freedom” itself.

In this way Evelyn Richter had a chance to go to the festival that was held the following year in Moscow. During her stay in Moscow some of the foreign visitors, Evelyn among them, were given a tour by a Russian art historian through archives that were normally closed to the public. There a great number of works in the tradition of classical modernism lay hidden. At the same time the public waited in long lines to see an Italian exhibit of modern art. The curious pushing and shoving of the people, their hunger for modernity and artistic experience in an atmosphere that was otherwise still dominated by timidness and shyness deeply impressed Evelyn Richter and convinced her to make her first documentary based entirely on her experience. This was also the beginning of her work “Austellungsbesucher” [“Exhibition Visitors”], a theme that she pursued for years.

People in front of works of art, in states of deep contemplation, alert attentiveness or physical exhaustion were for Evelyn Richter a chance to “observe mental activity as proof for the transmission of most delicate reactions which for me enlighten the hope that there is something essential in man”.4

By chance Evelyn Richter switched to a small format camera and she was able to complete her process of distancing herself from picturesquely staged single images step by step. Ever since, an intuitive and sometimes lively manner of working with the camer a that was based on physical movement became her way of photographing: the feel and the concepts of harmony of art photography formed the basis for her decisions in framing coincidental constellations of visual elements. In seemingly unimportant events the moment was seen as symbolic of [larger] conditions and as revealing history. A Leica that she was able to trade for valuables of her family in 1968, secretly and across the border, became an adequate tool.

After her return, contacts to members of the photographers’ association “action photographie” in Leipzig intensified, most of whom she had known since she was a student. During one of the officially very controversial exhibitions of the photographers’ association she met Arno Fischer, a photographer from Berlin who was in a comparable situation: in November 1957 the two of them went to Poland and in Warsaw they had contacts to reporters of the magazine “Swiat”, an event that reinforced their photographic ideas. In addition a joint exhibit took place.

Around 1960 both Arno Fischer and Evelyn Richter pursued, independently of each other, demanding book projects that came to an abrupt end when the inner-German border was closed. Looking for a way out of this financially and politically threatening situation Evelyn Richter found a new source of income in commissions from the VEB “Messeprojekt” in Leipzig. Here she met a small group of open-minded exhibition designers who took advantage of the fact that the GDR wanted to compete internationally in the field of trade fairs. Thanks to this there were sometimes also relatively demanding photographic commissions. The locations for these shoots were very often in production plants of factories and Evelyn Richter came in direct contact with the industrial wor king environment. But because only stereotypical and posed images were accepted that were to acknowledge the positive results of a socialist way of production these commissions themselves did not give her a chance to realize her own observations photographically.

Evelyn Richter’s interest was mainly in the female factory workers to whom she felt a special connection both through her basic experiences as a human being of the present and as a woman. The women workers who were decorated in the eyes of the law and idealized as heroines of production by propaganda in reality lead a rough and meager life amidst out-dated machinery. This contradiction soon became Evelyn Richter’s real theme – independent of its original context. Even though she had to fight for permission to shoot every time and despite the fact that her way of observational photography was v iewed with suspicion even by the workers themselves, Evelyn Richter was able to develop her method of long-term observation here. Her photography was oriented – as was the case later on – towards the depiction of people in their everyday social surroundings and their way of life. The photographic image was not solely “aimed at the recording of concrete social circumstances but at the actions of individuals. From this grew the photographs’ authenticity and subjective believability. However, this was only possible because of the artist’s vigorous energy that enabled her to persist against all odds.

First consultations with the publishing house “Edition Leipzig” increased her hope to have her own publication: just like Arno Fischer’s photographic work about East and West Berlin. Evelyn Richter’s book about women in the GDR became impossible after the wall in Berlin was closed.

After that the publishers refused to sign the already agreed-upon contract since every form of critique or even just every hint of a critique in public was to be prevented – and as such were denounced even unmanipulated depictions of everyday reality.

The consequences of the erection of the wall in 1961 can not adequately be described: after getting completely sealed off the real frame of reference, both spiritually and personally, was arbitrarily restricted; contacts to friends and lovers stopped, for many people irrevocably. The outrageous nature of building this wall was not accepted by Evelyn Richter as a permanent event. Just like the dogmatic discussions of artistic aesthetic in the 50-s this manner of creating political fact was felt to be grotesque.

Evelyn Richter’s understanding of the risks of an uncertain existence as well as her desire for personal independence had made it seem irresponsible to her to have a family. The sealing of the border, though not entirely unexpected, created finalities ev en in very personal matters for the rest of her life.

Her passionate interest in artists’ portraits which intensified after 1962 can be interpreted, as a theme, as the erection of a human counterpoint to those violent politics. She was able to secure her material existence through advertisement photography and through her work as a photo editor arranging exhibitions for the “Messen der Meister von Morgen (MMM)” [“Trade Fairs of the Masters of Tomorrow”]. Through this Evelyn Richter was able to maintain her status as a freelance artist, although increasingly out of the spotlight. She gave up taking her own pictures in this context more and more because of the existing regulations and she specialized in de signing exhibitions. The money she earned this way she invested in her own work and – in contrast to later years when the state offered commissions and stipends – this was the only way she could afford to take pictures at all.

Evelyn Richter’s deep love of music was the beginning of another project – portraits of musicians, conductors and composers – that she pursued over many years. Mostly at concerts and personal encounters she found a chance to photograph and despite the distrust that was everywhere she was able to develop friendly relations over the course of several years – as for example with the world-renown violinist David Oistrach from the Soviet Union. The expenses she paid mostly out of her own pocket: towards the end of the 60-s there were some commissions from the magazines “Freie Welt” and “FF-dabei” in Berlin.

Evelyn Richter concentrated on the comportment and the impression on others of a few outstanding artists and she tried to fathom the secret of their personal charisma and their power to convince in their effects on each of their particular surroundings. At the center of her depiction [work?] is the communication of attitudes, of hard work and complete personal involvement as the basis for spiritual work, the way she experienced it in musicians like Oistrach.

Making music – simultaneously an immense psycho-physical stress and an artistic ability to enjoy – becomes a metaphor for creative achievement. Her personal style of “simple, clear composition based on an unpretentious moment” reached its peak.

In doing this Evelyn Richter remained true to a basic conviction that understands the photographic image as an authentic consequence of true human expression and that opposes the manipulation of the photographic image with the genuineness of experience and the author’s credibility. More and more she came to see the photographic book as the only adequate form of publication – a combination of single images and sequences with a temporal development of actions which are based on psychological tensions and which provoke a comparative contemplation of the pictures.

After working out the basic concept she contacted the Henschelverlag in Berlin and they accepted her idea of producing a photographic monograph on David Oistrach. Since the beginning of the 70-s Evelyn Richter had been working intensively to perfect the pictures as well as the concept of the book. For this reason it hit her very hard that despite all her efforts she was not allowed to follow Oistrach’s personal invitations to attend his concerts in West Berlin. Instead of paying the few pennies for the short train ride to West Berlin, again and again she had to travel thousands of miles to Prague and Moscow to see the musician at work.

In order to render the connection between working environment and lifestyle more transparent she developed a combination of documentary study and psychological interpretation that was to be complemented with an accompanying text. In their sequence the photographs were conceived as elements of an experiential crescendo comparable to the experience of a musical piece. But especially the text part was unsuccessful and there was a constant incongruence between the demands of the author and the publisher. Her passionate involvement was based on her intense need for self-expression, the desire to carry her ideas through in as pure a way as possible and to realize her book as one whole work of art [Gesamtkunstwerk]. To this end she was willing to accept a very heavy burden – not to mention the fact that due to the shortage of goods in the GDR she had to work under very modest circumstances as it was and that the purchase of materials necessitated larger and larger expenditures. The publishers pursued their own goals in using Evelyn Richter’s concept and photographs – e.g. lucrative licensing in t he West from which the photographer would get no share – and because she insisted on having the responsibility for the entire project problems between her and the publishers increased. Evelyn Richter’s artistic claim collided with other existing interests and the situation developed into an almost typical conflict between a non-conformist artist and the established state structures.

These structures explicitly opposed any form of strong-willed creativity and supreme subjective achievement. What was wanted instead was a conforming to an atmosphere of mediocrity and resignative insight. Completely unaffected by market-economical considerations Evelyn Richter was striving for perfection and for control over all aspects of production of her “Gesamtkunstwerk” book. Through her attitude she made it very difficult even for sympathetic partners to work with her and this became ever more noticeable later.

Despite this tense situation Evelyn Richter at the same time developed another project for a book that was dedicated to the composer and conductor Paul Dessau. In this case, too, she was working on an integrated concept of photographs and text in the sense of an expanded depiction. Again the book was planned to be subdivided by inserted pieces of text. W hen the book on Paul Dessau was published Evelyn Richter, by and large, had been able to assert her own ideas of book composition against the VEB Musikverlag. But she also had to accept some major changes. The loss of editorship and impending legal batt les made other projects – a book on conductors, among other things – impossible and effected a deep psychological and physical crisis for Evelyn Richter. General exhaustion as well as work-related stress worsened the effects of an illness that prevented her from working for several years and that left her with permanent health problems. In this situation Evelyn Richter, out of the blue, received a commission to photographically illustrate a popular-scientific book on developmental psychology. A concept by the psychologist Hans Dieter Schmidt existed already.

Even before that assignment Evelyn Richter had been observing – with her camera -one of the children of her family and she was able to use some of that material. Coordination with the author of the text happened without any major disagreements: on the basis of mutual acceptance Evelyn Richter was able to realize an interdisciplinary way of working in her description of a social problem. An approach that – with reference to the tradition of the “Bauhaus” in Weimar and Dessau – she had been demanding in vain so far.

After some time Evelyn Richter withdrew some of her own pictures and included photographs of other artists that concentrated on conflict situations in a variety of milieus. The “different sequences of verbal and visual logic”, the different objects of pictures and text became a valuable experience.8 The topic itself bore a potential for political conflict since it depicted, among other things, the accommodation of large groups of children in the day-care centers of the GDR. The popularity of the book – it appeared for the first time in 1980 – was partly due to a considerable deficit in information and a need for communication in an area that was as a whole disrupted in its communicative balance.

After completing this project she had the opportunity to fill a teaching position that had become available at the Hochschule fuer Grafik und Buchkunst [College of Graphic and Book Arts].

This was certainly an especially tricky situation since 30 years earlier she had been ex-matriculated from just that art school. However, she had always exerted an influence on the college – from without – and she still maintained personal relations to some of her old classmates who were now working there and who supported her cause. Moreover, there was a favorable constellation even on an official/political level: they could not help but notice her unusual energy and her rank as an artist even if only rather reluctantly in the beginning.

Since 1981 a full-time employee, Evelyn Richter was able to work in a by now relatively tolerant atmosphere. And she was able to communicate her ideas of a socially motivated, in theme and concept clearly determined photography. Her insistence on a broad artistic education and sensibility, on a correlation between artistic genres as well as her unwavering belief in the basics of an individual search for truth guaranteed her the interest of her students. However, the teaching environment itself left something to be desired: the equipment in the photography department was in very bad shape; and the number of students was deliberately kept low -only 4-6 students per year were accepted in the entire country, plus a number of external students.

The college acted as a protective umbrella for the small number of students and teachers and over the years it produced quite a number of important photographers. But it was a far cry from a spiritually stimulating environment because of the lack of competition.

A much younger generation of photographers partly “withdrew from the dominant culture and its institutions and searched for their own path outside the political system”.-9- And their efforts were noticed even behind classroom doors. The younger generation increasingly questioned the argumentational effectiveness of the traditional visual languages, as for example classical Live photography. The experience of powerlessness in the realization of their personal concepts and last but not least the fact that their professional as well as private lives were dominated by the lack of even the most basic things made the “aesthetic of skepticism”10– more and more apparent – in Evelyn Richter’s work as well. The persistent constriction of their lives and above all the depravity in terms of cultural tradition that could be felt everywhere had their effe ct on Evelyn Richter – more and more hopeful impulses disappeared for good. In this climate of constant frustrations only few events provided relief: most of all an invitation to the “Rencontres Internationales de la Photographie” in Arles in 1987 where Evelyn Richter’s work was one of the main contributions.

Since the opening of the Wall in 1989 Evelyn Richter has been in constant motion, with her typical restlessness as well as her difficulty in organizing the practical things of her life in a rational manner.

For this reason she has not yet started the pending overview of her accumulated works; even prominent honors, like the Honorary Ph.D. she received from the Leipziger Kunsthochschule [College of Art in Leipzig] as well as an important photo award have not been able to trigger anything meaningful in this direction.

Even so: the perception of Evelyn Richter’s work has changed in many ways. Many of her photographs are historically specific to the East German state. But after its disintegration her pictures did not lose their power. Quite in the contrary: their innate qualities have only become clearer. Evelyn Richter’s photographs are statements about general phenomena of humankind and humanity in this time – the time after WWII, which in East Germany has always remained the post-war era. Even so, the – at first glance – melancholy features of many of the people she photographed did not forebode the “status melancholicus” in anticipation of the historic failure of the GDR. A differentiating eye will see many facets of human expression: complete absorption and a dreamy state of reverie in the portraits of gypsies and young factory workers; meditative concentration and creative fulfillment in many artists’ portraits; as well as numb depression, spiritual weakening, deep pensiveness, self-confidence and leisure.

The woman at the Linotype, the returning worker, the exhausted musician taking a break are all participants in a message between resignation and promise. A message that refers to a concrete, historical situation as much as essential, hopeful abilities of the human race. Insofar as there is no reason to draw strict parallels between the fate of a state and the content of an artistic oeuvre.

History is obviously neither predetermined nor ending. And this is true for Evelyn Richter’s photographic work as well which reflects her desire “to create contacts [Beruehrungen]. Contacts in the sense of spirituality and concern.”–12–

Note: a catalog has been published on the photographer’s work: Staatliche Galerie Moritzburg Halle (editor), Evelyn Richter. Zwischenbilanz. Photographs from the years 1950-1989, Halle 1992, with texts by Ludger Derenthal, Ulrich Domroese, Andreas Krase ISBN# 3-86105-071-7

Out of Control: Photography from East Germany

Karla Sachse

Foreword

Wolfgang Kil

Ostkreuz: An Origin Stopped in Time

Ostkreuz Portfolio

Sibylle Bergemann

Harald Hauswald

Ute Mahler

Jenz Rotzsch

Harf Zimmerman

Andreas Krase

The Work of Evelyn Richter

Evelyn Richter Portfolio

Susanne Klengel

The Near Distance — “Cultural Otherness” in the Two Germanies

Matthias Leupold Portfolio

John P. Jacob

Postscript

Translations by Chris Egger, 1993

Evelyn Richter Portfolio

Out of Control: Photography from East Germany

Karla Sachse

Foreword

Wolfgang Kil

Ostkreuz: An Origin Stopped in Time

Ostkreuz Portfolio

Sibylle Bergemann

Harald Hauswald

Ute Mahler

Jenz Rotzsch

Harf Zimmerman

Andreas Krase

The Work of Evelyn Richter

Evelyn Richter Portfolio

Susanne Klengel

The Near Distance — “Cultural Otherness” in the Two Germanies

Matthias Leupold Portfolio

John P. Jacob

Postscript

Translations by Chris Egger, 1993

The Near Distance — “Cultural Otherness” in the Two Germanies, Reflections from a West Berlin Perspective

Susanne Klengel, Berlin, March 1993

Since the collapse of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989 we have been living in a turmoil of events–or so it seems compared with the self-contented, saturated decade of the 80s as it was generally experienced in West Germany. At times these events occurred in such quick succession that, neither in the West nor in the East, was it possible to follow the developments mentally. Mostly for this reason it is difficult at this time to reach conclusions about the latest historical developments and the present situation which are not heavily influenced by a reflection of daily occurrences. The strongest, persistent cause for irritation that occurred after the disintegration of this separating border was certainly the realization of a basic “otherness”. And w ith it a renewed polarization between “citizens from the West” and “citizens from the East”. The vision of national unity (both political and cultural) that has been kept up for decades, at times pathetically, at times in a mere political-rhetorical fashion, has been replaced after 1989 with a new awareness. This new awareness that was felt to be something painful by most people resulted from the fact that the two German states had developed very differently after WWII.

In retrospect it is almost surprising that politicians as well as broad sections of the public had been taken so unawares by the differences in the way people think, act and express themselves in East and West Germany. Because of the German-German border over the years a peculiar cultural difference could develop between two places in immediate proximity. But in the West this fact was not really noticed in political and ideologic discourses. The new polarization between East and West can therefore in part be traced back to a sudden, mutual disillusionment about the other group. All the differences, this “otherness” was felt to be a burden and only rarely has it been seen as a chance for the West, too, to rethink it’s own cultural borders.

These days everybody is talking about the complex structure of this “otherness” and it is therefore susceptible to platitudes of all sorts. In the following [text] I would like to clarify this otherness in a few points without referring specifically to any daily occurrences. In doing this it is not enough to merely list, explain, and categorize the relevant pieces of circumstantial evidence end thereby prove the “otherness” of the other group. At least as important is the aspect of self reflection of the “speaker” which in my case is done from a West Berlin perspective. The latest developments in anthropology (a discipline that is highly self reflective) show that, especially when dealing with themes of cultural otherness, this kind of self reflection must be taken into consideration. One of our concerns must always be the critical evaluation of our own point of view, our relation to the other and the type as well as the patterns of our discourse about the other. 1 How much this evaluation of one’s own point of view has been neglected especially in West Germany is sometimes discernible in articles that deal with the new German German relationship:

There is a general lack of perception {in the West, Susanne Klengel}, everywhere it is business as usual. And this can not be obscured by the fact that much is being said and written about the East. So far the East has not found access into the West’s daily life and thinking. 2

In the years after 1989 this inadequate perception of the other, that “wall in the head” soon became a topic in political discussions and it is being lamented to this day. It would be inaccurate, though, to see this act of drawing a mental border as an expression of mere stubbornness because it is also a protection against the sudden loss of orientation a nd the turmoil of events. In the following observations by Angelo Bolaffi (a philosopher from Rome who chose to live in West Berlin in the 70s and 80s) the scope of this loss of orientation and insecurity in the face of the disappearance of the Berlin Wall is expressed drastically: “In the beginning I perceived only very un-clearly what was happening inside me. Disbelief, a feeling of emptiness and a fear of expanses. A downright case of agoraphobia.” Up until then the German German border had in various ways managed to secure identities in this case that of an Italian left wing intellectual:

The sudden lack of a wall shocked me: even though I was in places where I had spent important (if not exactly easy) years of my life I noticed that I had totally lost my orientation. I had literally gotten lost in that space that had opened up before me. The fall of the Wall had produced a completely unexpected perspective. –3–

In a Kantian turn Bolaffi finally copes with his deep insecurity and he comes to see this new and surprising perspective as a chance to break out of a mental condition in which the wall had defined a paradoxical level of expectations even for left-wing intellectuals. Out of his individual experience Bolaffi extends to all people concerned a missionary gesture that has the character of an appeal for a re-orientation and, on a mental level, an emancipation. However, what is necessary for a mental re-orientation is a knowledge of and a certain sensibility for this Otherness which is still perceived as something irritating. Especially since in the new inner-German East-West relationship the West’s discourse is clearly seen as dominating or even colonizing. Bolaffi envisions a mental emancipation of each individual through the realization that one’s [mental] horizon was formerly very limited and through a concurrent “reclaiming of one’s freedom to judge”. But this vision is confronted by the difficult legacy of a cultural/mental inequity between a seemingly stable West and an insecure East. For this reason the question we need to ask ourselves today is how we can deal with the problems caused by the sudden realization of this otherness. In the following [text] I would like to broach this question and to open a historical dimension of this otherness experience in the contacts between East and West Germany that goes back to the decade before the opening of the Wall. This might help to counteract the atmosphere of self-affirmation in the West to some degree.

In the decades before the opening of the Berlin Wall very stereotypical pictures of the other Germany emerged on both sides. Let me point out only that – with the exception of constructed ideological phantoms – there were the [following two stereotypes]: on the one hand we have the legend of the dreariness and dreadfulness of the GDR which people opposed with their private and at times touching search for a small piece of (often material) happiness in the grayness of everyday life. On the other hand there is the myth of the glittering and colorful West that invaded GDR homes every night via TV. This is a topic I do not need to elaborate on here. Stereotypes of this kind have continued to exist to this day in one form or another.

But even so there were (in the words of Lutz Niethammer, a historian from Nordrheinwestfalen) attempts “to gain a real access into the secrets of GDR culture”, long before the Turn. These attempts were made out of an interest that was not politically, economically or ideologically motivated and went beyond the stereotypical conceptions.–4–Usually these attempts were based on some kind of “field work” and were coupled with a curiosity about GDR culture which, very often, caused mutual astonishment. For many of these West Germans a [short] ride into the GDR seemed more exciting than a trip to Brazil or Japan and the reason for this was a peculiar kind of fascination with this other Germany that was so close yet at the same time so distant and that elicited an ambivalent kind of exoticism based on this tension between familiarity and unfamiliarity. Crossing the border from one half of Berlin into the other half resembled a passage into a different world where not only the appearance of the storefronts, the packaging of goods or advertisement slogans attracted one’s attention but where even everyday language, with its unusual vocabulary, seemed to be a little different.

Before the Turn the historians of the oral history project by Lutz Niethammer did a study of “the life and social structure of the Ruhr area”, intending to do a comparable study in the GDR.–5– And they, too, admit a [kind of] curiosity and nervousness caused solely by the different nature of this close distance:

On this trip Dodo was particularly excited because of her (at 37 still undiminished) desire for the new, for people and for the adventure of an ethnology of the inland behind the Wall. –6-

This phenomenon (the West’s fascination with this close distance) can be explained a little more precisely with the help of a specific aesthetic experience that a few people had during their contact with the GDR, especially in West Berlin in the 80s. Hints of the existence of such an aesthetic appeared in lively reports of travels and excursions to East Berlin and the GDR, in collections of memorabilia from the VEB (Volkseigene Betriebe = state-owned factories) that seemed to have been put together according to strange criteria or in the conscious usage of East German colloquialisms. It was not the exclusive goal of this peculiar phenomenological approach to the immediate vicinity (and the aesthetic that resulted from it) to transport curios from the “state-owned” everyday life back to the West and to collect them, although this aspect was [certainly] not unimportant. Most of all it was a conscious play with semantic layers that could be won from the world of GDR “objects”. Elsewhere I have tried to determine the mechanisms of this aesthetic experience with help from Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp” (1964) and also considering post-modernist theories of aesthetic and anthropology.–7–

At this point it seems important to me to point out once more the deconstructionist process that is characteristic for this aesthetic. Starting points were forms of representation from the GDR’s everyday life with their strange effect, semantic irritations that were hard to disentangle for people from the West: the system of cultural symbols, the signifier and the signified, functioned in totally different ways and the reason for this was (of course) the different political system. In order to understand this strangely close other the Western mind, when looking at the world of GDR objects and everyday life, was always searching for characteristics that would make the official face of the socialist system apparent in the way things were arranged, in the state’s advertisement strategies, in the style of things and even in people’s language or mentality. The condensation of the socialist utopia in its catchy slogans and in the official political-cultural representations had, through its coherence, purism and logic a certain characteristic which, according to Susan Sontag, the most convincing forms of camp have, too: it was unintentionally naive or at least it appeared that way. Pedagogic and sometimes a bit awkward advertising slogans like “well packaged is half-sold”, cigars of a brand called “speechless” or the neon sign “Plastics and elastomers from Schkopau”**1** (unforgettable for every transit traveler between Germany and East Berlin) were meant completely serious.

The GDR collections were created by plucking certain objects from the coherent appearance of the GDR system and transferring them into one’s own, Western world: from kitchen utensils and paper products to plastic products, toys and souvenirs. The VEB objects that had been removed from their original context were then, in their Western surroundings, recombined to a new ensemble which, in its components, still reflected the GDR in a fragmented and distorted manner. In the other Germany the East-phenomenologists of the 80s saw many of the things and words in quotation marks so to speak. The object s were a kind of ironic decoration and elements of a game that was understood and shared by a small circle of initiated people. These East-phenomenologists could be considered a strange species of peeping Toms and “listening Toms” that were constantly on the prowl for new things, words and stories from the real, existing socialism. The idea to actively arrange the social reality down to its details according to a [master] plan and with an educational purpose shimmered through again and again in the GDR aesthetic of everyday life. And this aesthetic was a cultural field that, in the face of Western analysis, proved to be amazingly coherent. By means of deconstruction an epistemological balancing act became possible: apart from the political, economic and scientific analysis’ this way of looking (that only appeared to be phenomenological) was constantly searching for inscriptions that made the totalitarian idea of this socialist society apparent in all its words, its behavior and its everyday objects and that thereby demasked it.

This does not mean, however, that as a result a stereotypical judgement was reached about the society or the culture shaped by this idea. The deconstruction of the official meaning did not lead to any precisely formulated critique of the official representation but rather to a subtle sema ntic subversion that playfully fathomed and thwarted the different levels of meaning. There was always the attempt to read the GDR as a cultural entity as precisely as possible “against the grain”. Just how much a finely nuanced knowledge of everyday reality in the GDR had been a prerequisite for the application of such deconstructionist strategies becomes apparent only today. So in retrospect this deconstructionist approach proves to be a bridge to a more precise perception of the after-effects and inscriptions which the other political/cultural system, after its disappearance, left behind in the way people in the former East Germany think and act as well as in their mentality. With this background many aspects of the behavior and the structure of argumentation of ex-GDR citizens which, with its different logic had irritated all those in the West who had up until then lived with their backs to the other Germany, did not seem all that strange any more.

But, as I noted initially, in describing this aesthetic experience we must also reflect on the point of view of the speaker as one more essential aspect. It is only in this manner that this aesthetic experience can simultaneously become an experience of cultural otherness. It is certainly no coincidence that in the attempt to describe GDR everyday culture concepts from anthropology and ethnology come to mind time and again — two disciplines where especially in the 70-ies and 80-ies a critical self-evaluation led to a new definition of their basis for scientific argumentation. Questions like “Who has the authority to speak for a group’s identity or authenticity?” and “What are the essential elements and boundaries of a culture?”–8– show us that well-known pairs of concepts like “near and distant”, “one’s own and the other/alien”, “wild and civilized” or “center and periphery” need to be negotiated in a field of ever more intrinsically interwoven relations. The GDR experiences could not be reduced to simply being part of the “other”. They always were and still are also part of the “own”: out of this ambivalence of apparent familiarity and unfamiliarity grew a relationship of tensions that exists to this day. The traditional divisions of the ethnologic field into “distant” and “close”–9– had to become shaky especially [during this evaluation of] the “ethnology of the inland behind the Wall”.

Because the processes of modernization were not simultaneous in the two countries the GDR reality, almost like in a puzzle picture, kept making aspects of the “own” visible, mostly in the form of memories of a not-so-distant past:

At first one feels reminded of the 50-ies (or even earlier years) but the two do not coincide with one another — this activates a process of reception that keeps oscillating back and forth. The consequence is a kind of floating between an object and its inner image, between East and West. –10–

This seemingly nostalgic tracking down of traces of the past or one’s childhood in the old-fashioned-looking reality of the GDR is not so much a sign of sentimentality (every-day life in the GDR was much too dull) but rather an essential part of this otherness experience. Fascination and a simultaneous unease were the extremes of this shimmering and comp lex relation that expressed itself most clearly in the encounter with the other German language. The oral history researcher Lutz Niethammer aptly called this ambiguity and the subversive potential that was used in GDR every-day language a “labyrinth of semantics”:

The encoding of all communication with multiple meanings was, as a rule, not easy to decipher and required a heightened attention in order to perceive not just one layer. It had its roots in the fact that structures of the authorities were ever present but were not or could not always be enforced. And it was exactly in these gaps that people relieved themselves through their sense of humor; a usage of language that plays with the borderline of truth and taboo and that hones its skills in this game.–11–

In the aforementioned aesthetic and anthropologic approach to GDR culture these types of communication formed one of the most astonishing fields of experience: similar to the way Niethammer described it there was always a renewed sense of wonder about the strangeness of expressions, about subversive shifts in meaning with various allusions, about ambiguities and strategies of de-clarification. But right here an essential and discomforting difference can be noticed between those who speak (in East or West): through that Western, seemingly phenomenologic approach the cultural ensemble of the GDR people’s democracy was deconstructed in its propagated totality, the official representations were, in a respectless/playful manner, dissolved into ambiguities and through this the state’s claim on all truth and meaning was deliberately questioned. Bu t on the other side [of the Wall] strategies were developed to hold one’s ground as an individual in the face of a given truth, which is to say the state power, through the use of ambiguities, deception and other means of lingual subversion.

For this reason there was in this an existential honesty and necessarily a truth that, by definition, can not play a part in the described deconstructionist processes [of the West]. But exactly as a consequence of this one became even more fully aware of the cultural differences within one’s own language. In the discussion of the German-German otherness-problem we need to evaluate especially this difference which requires a high degree of reflection about the form of our discourse as well as our own point of view. Today there is a wide-spread believe that we can uncover an ultimate “truth” in respect to those decades when the socialist state had claimed all truth for itself: only a tissue of lies, so goes the argument, could have fallen apart like that. It is a tragedy that, in proceeding this way, there is a renewed division in which the past is either denied or pitilessly revised: it is either suppressed or it is searched for a “pure” truth (as becomes evident in the way the Stasi **2** files are being handled). And again this binary constellation makes it possible for the former West to distance itself since it has seemingly nothing to do with these problems and therefore believes all it is required to do is help [the former East Germans in coming to terms with their past].

In my opinion all of these questions are important if one wants to go beyond a chronology of historic events and relations when discussing the cultural forms of representation of the former GDR. In the meantime ethnology has been joined by archaeology: only broadly based “archaeological” studies will lead to a thorough understanding of the processes of hybridization that occurred when these two different German cultures met. It is therefore important to secure the traces, which that other culture has inscribed in everybody’s memory.

After the exorcism on the range of products from VEB production (in the years after 1989), when kitchen utensils, light bulbs, clothes and other everyday objects were sold in flea markets in large quantities and dirt-cheap one must now start an archaeology of everyday life in the GDR in private collections, company archives (which are becoming more and more sparse) or even in museums.–12– On the other hand there is the East German politician Wolfgang Thierse who, after the Turn, coined the appeal that the citizens of the former GDR should start “telling each other their stories”. This is one of the key phrases for the understanding of a past everyday world which so noticeably and perceptibly reaches into the present of the unified Germany.–13–

Only today can we fully appreciate the value of all those undertakings that (before and after the Turn) tried to document the spheres of living and everyday culture from a point of view not motivated by political or ideologic interests exclusively. At this point I would like to mention two examples out of many. The first one is a work called “Das Berliner Mietshaus”[=The Apartment Building in Berlin], created by the author Irina Liebmann in 1982, which documents the history of a house in East Berlin through the stories of its tenants. The second one is a project by the Deutsche Film AG (DEFA) [=German Film Inc.], a long-term study of the “Kinder von Golzow” [=The Children from Golzow], whose lives in the GDR have been documented with the camera since 1961.–14–