Born out of opposition to the totalitarian darkroom... this is the penultimate art of spiritual confrontation. -- Jerzy Kosinsky, Introduction to Out of Eastern Europe, 1987

Introduction

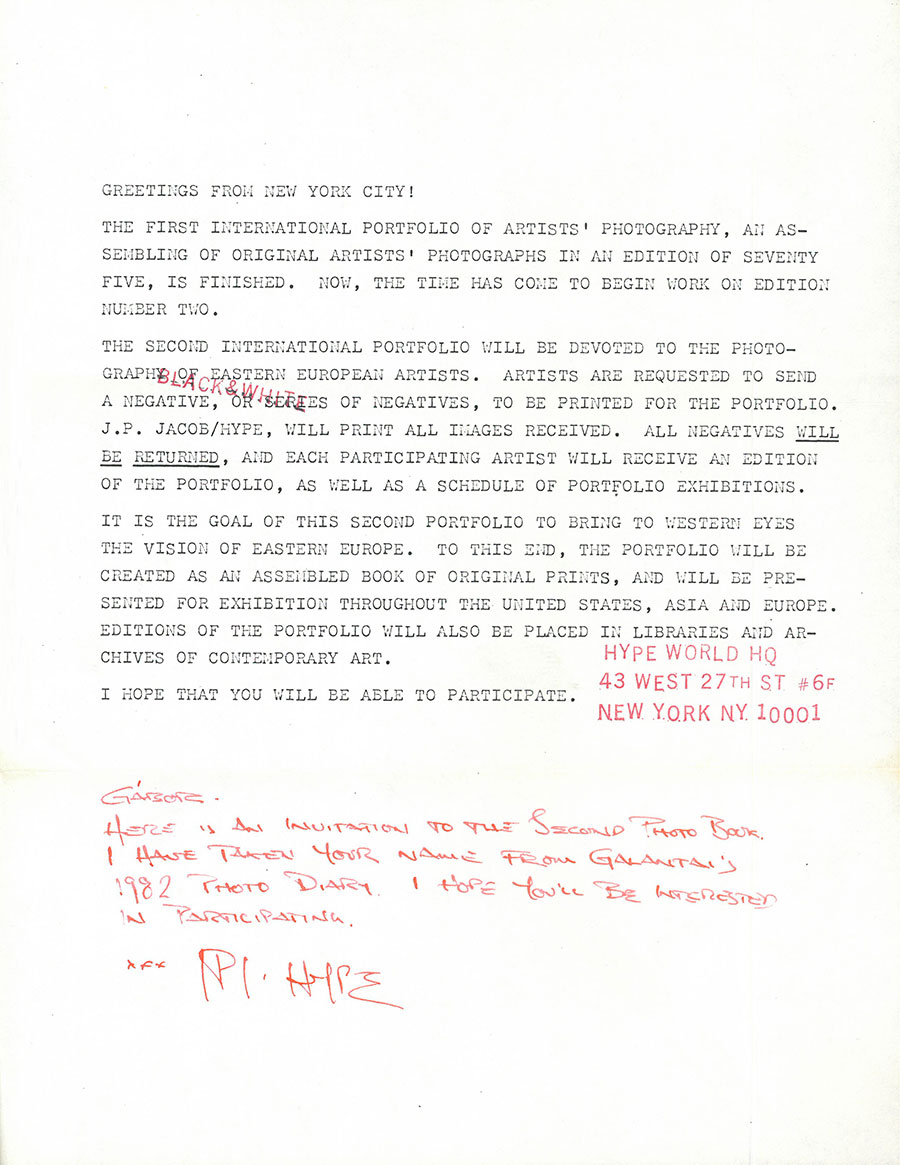

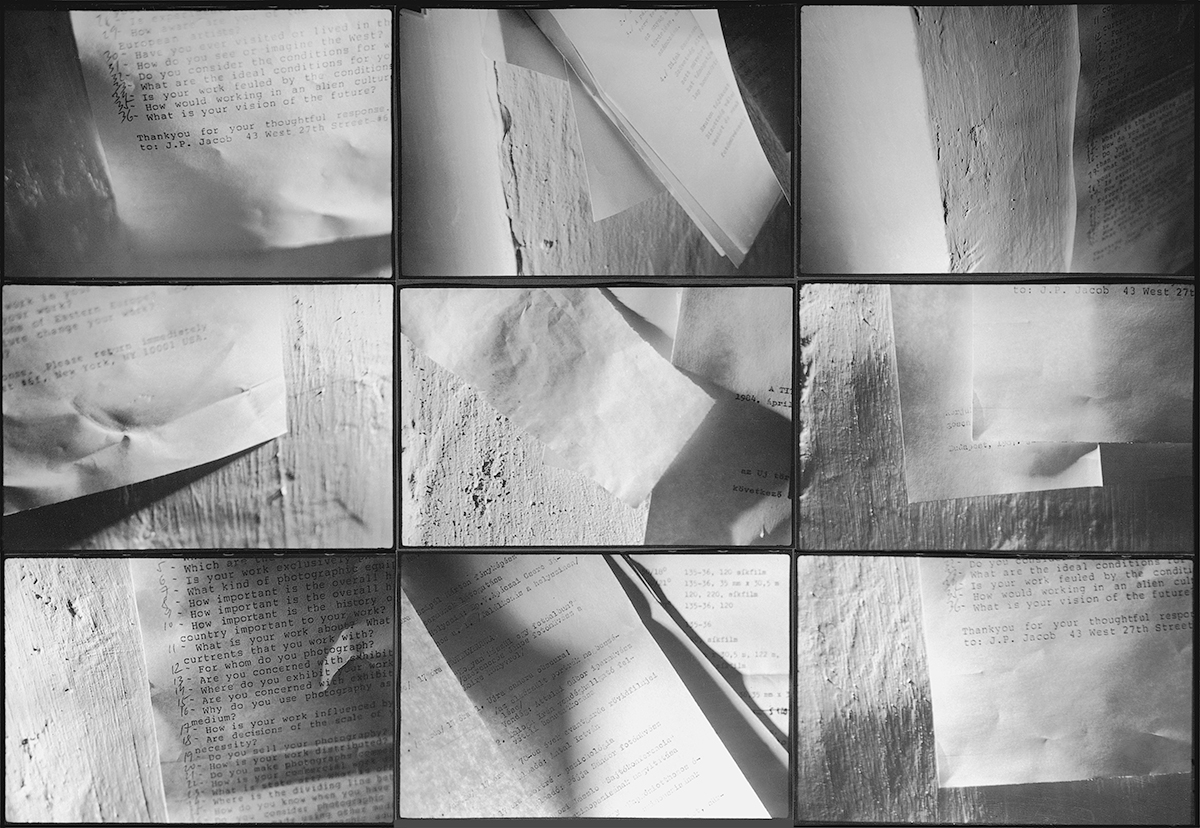

Jacob began to work with Russian and Eastern European artists in the early 1980s, in conjunction with his multi-year project the International Portfolio of Artists Photography. Motivated by problems encountered by Eastern European contributors to the First Portfolio, he focused the Second Portfolio, begun in 1984, on Soviet and Eastern European photography. At the time, Jacob’s grasp of East/West geopolitics was poor. The invitation to contribute was sent to Russia, to artists working in the Soviet Bloc countries, and to artists in European Socialist countries such as Yugoslavia. The former and latter quickly distanced themselves from the label “Eastern European.” What he lacked in knowledge Jacob sought to make up for with enthusiasm. Invitees were asked to share the invitation with other artists. To limit postal censorship, and to lower costs for contributors, artists were asked to mail a single photograph or negative in an ordinary envelope, which Jacob would reproduce or print for the Second Portfolio. In 1984, Jacob printed and exhibited a selection of the works received for the East European Art Exhibition at No Se No Gallery, NYC.

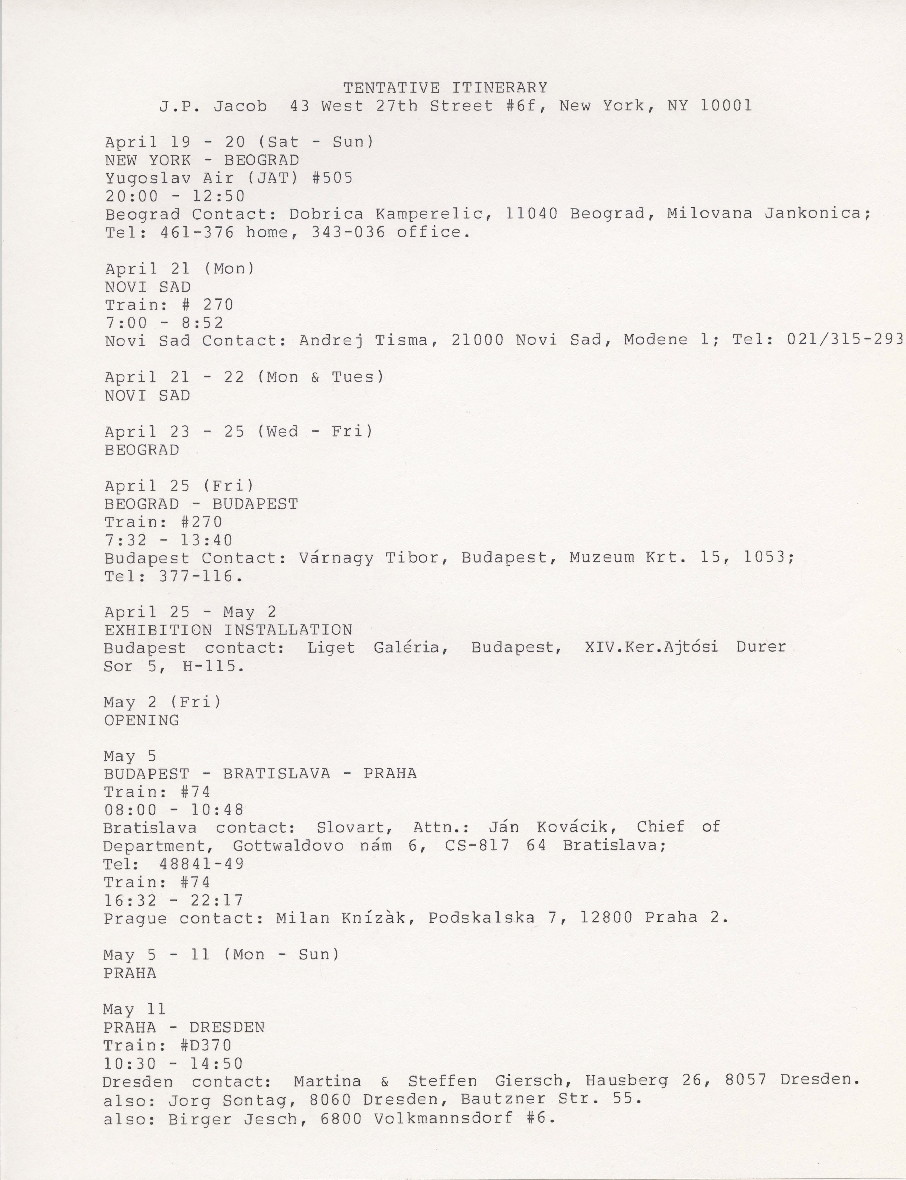

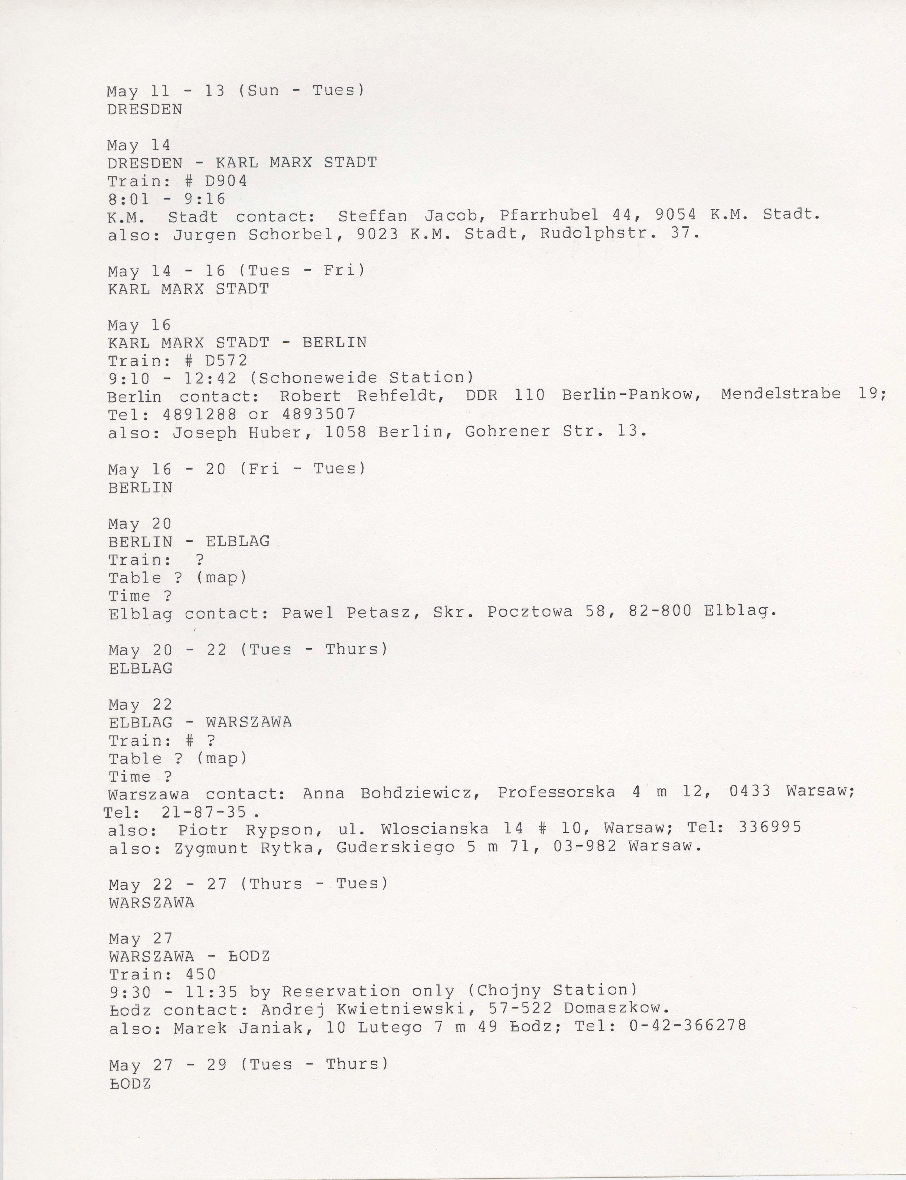

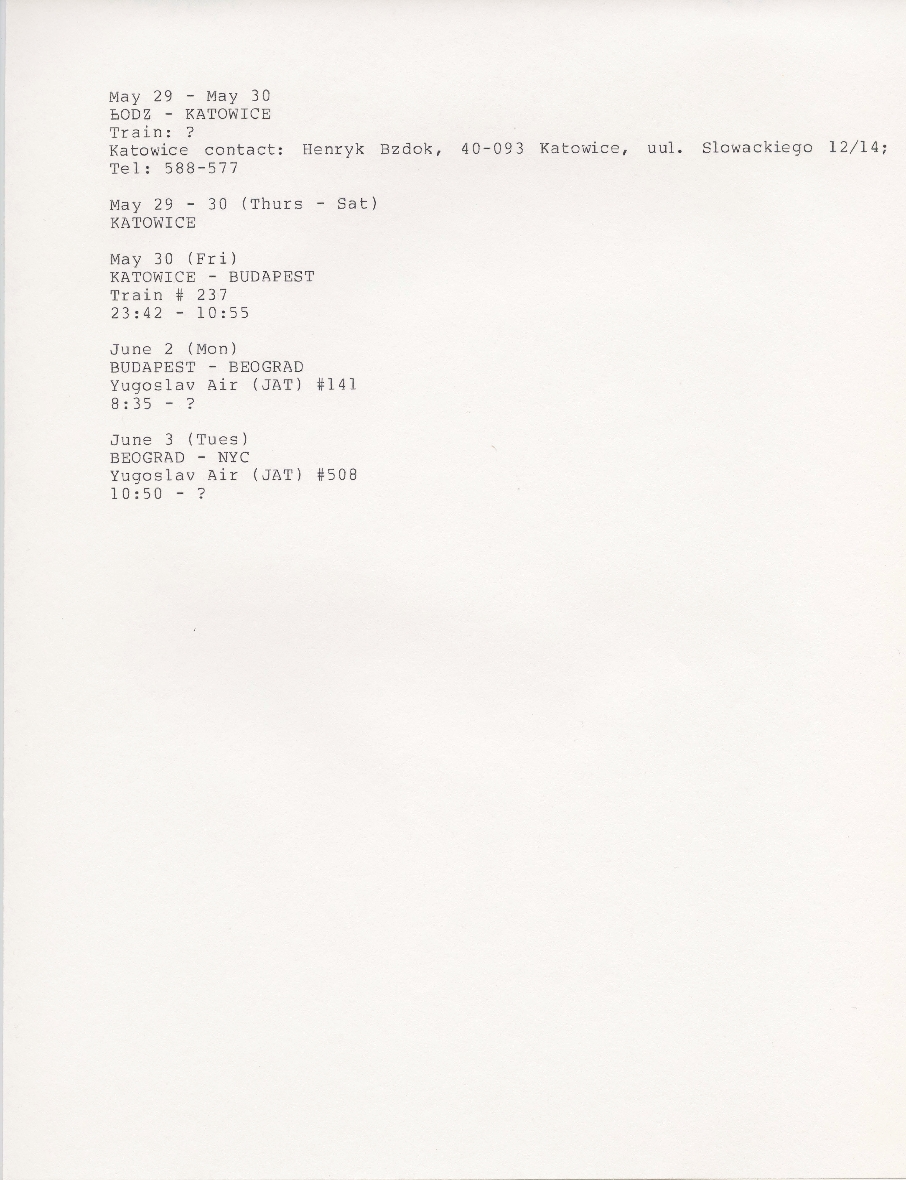

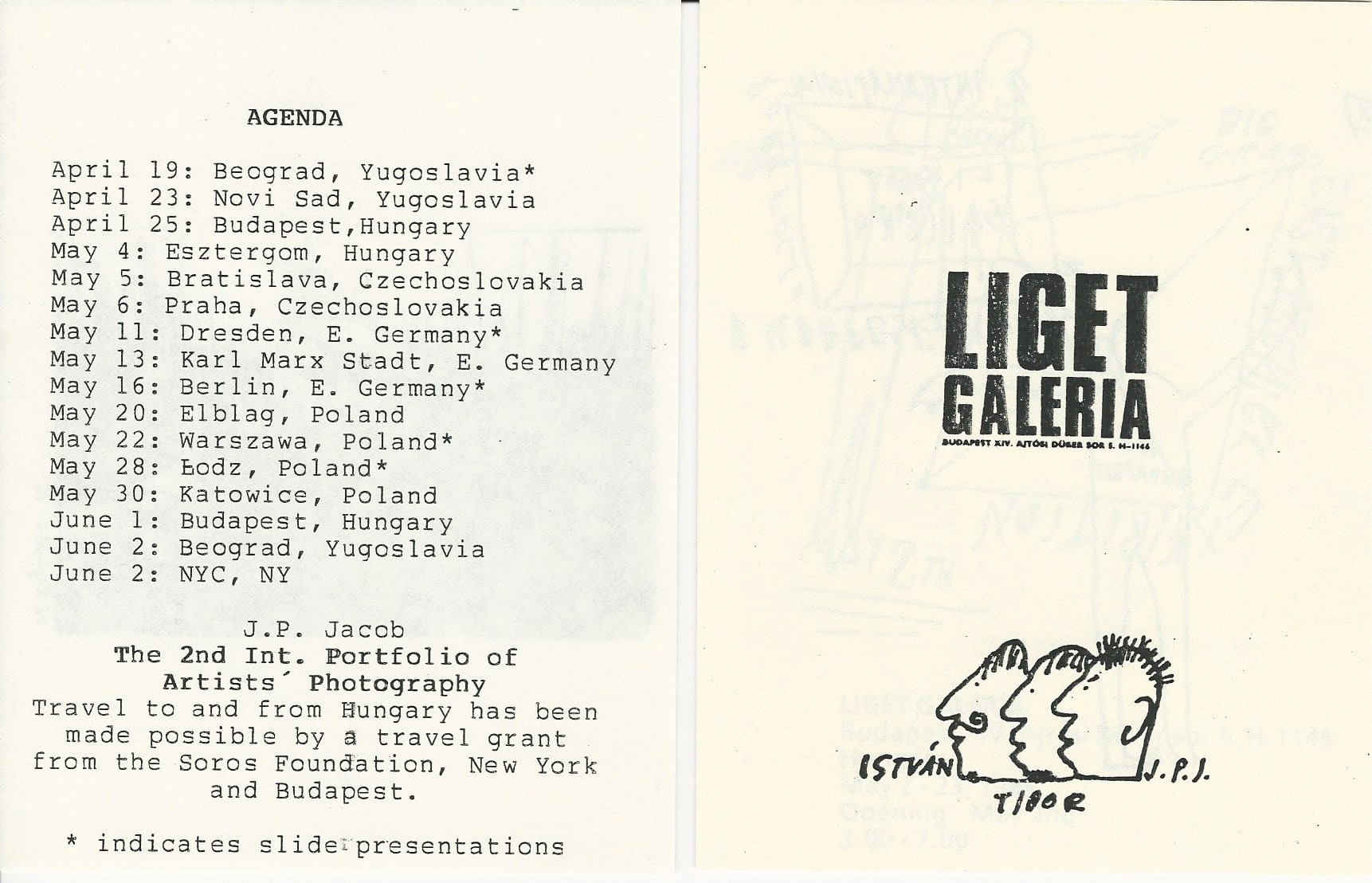

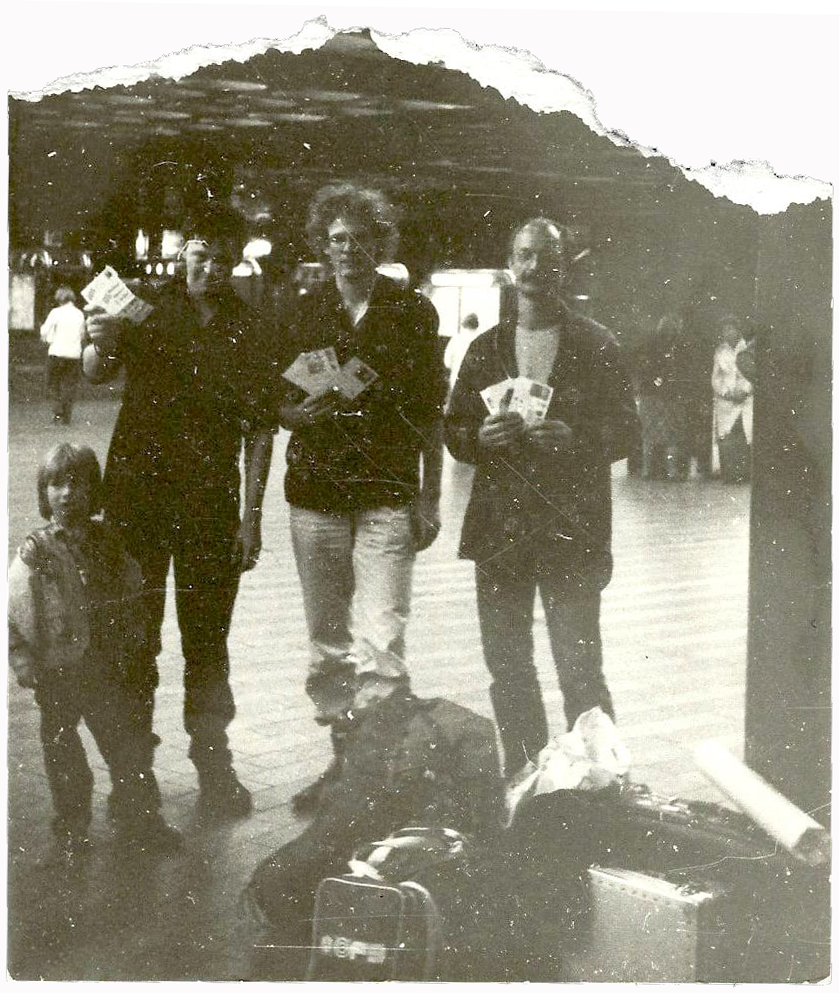

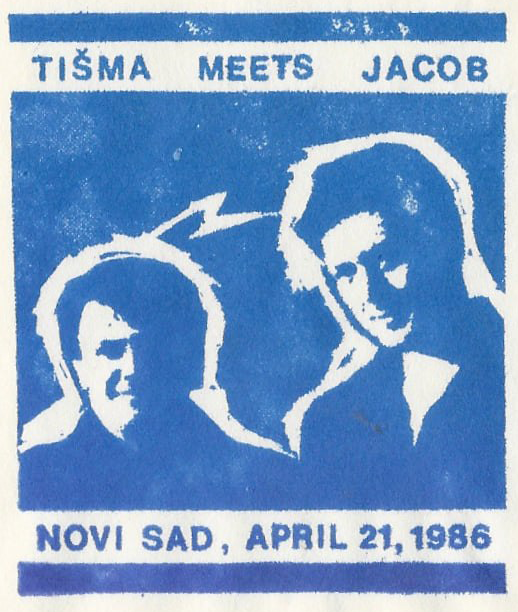

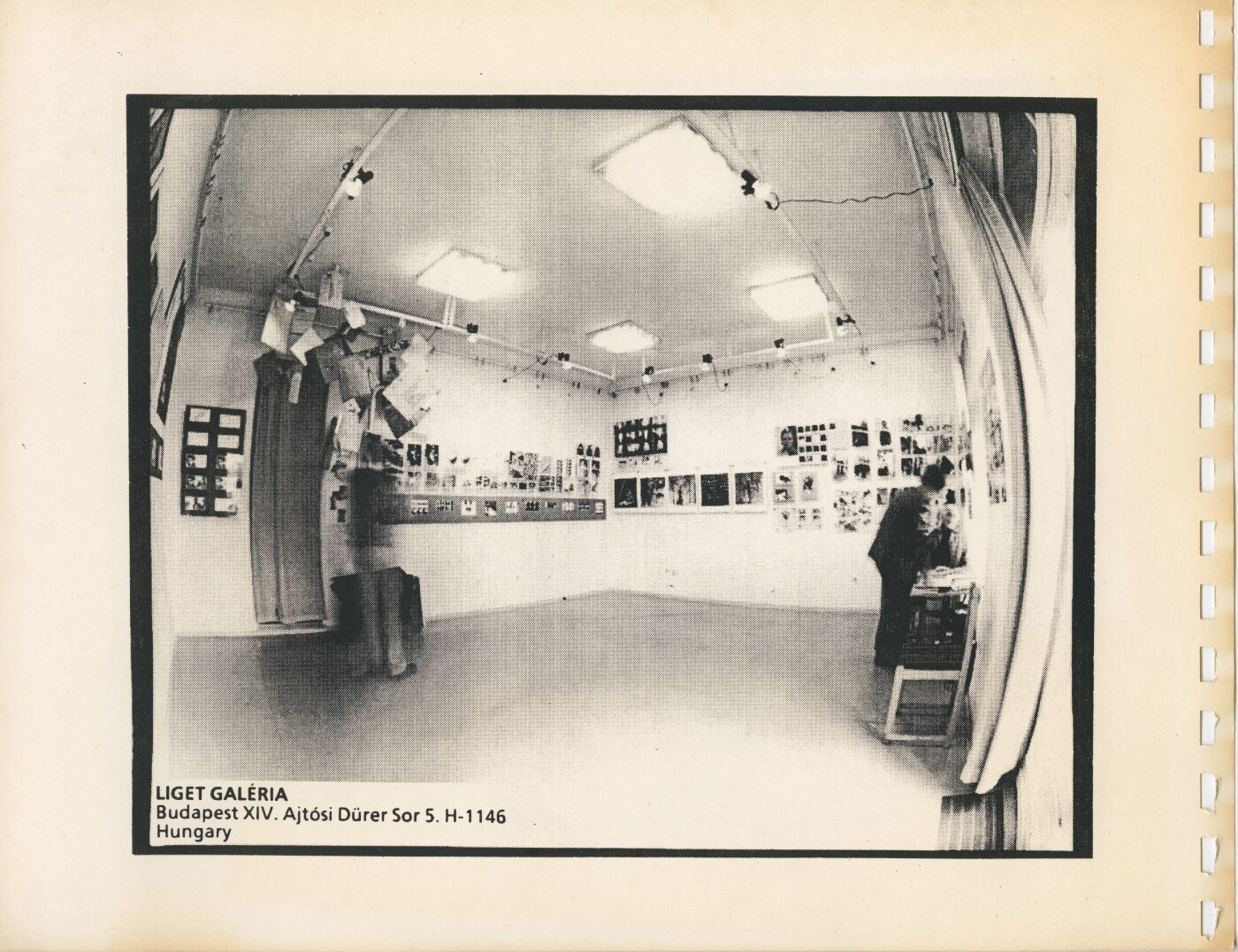

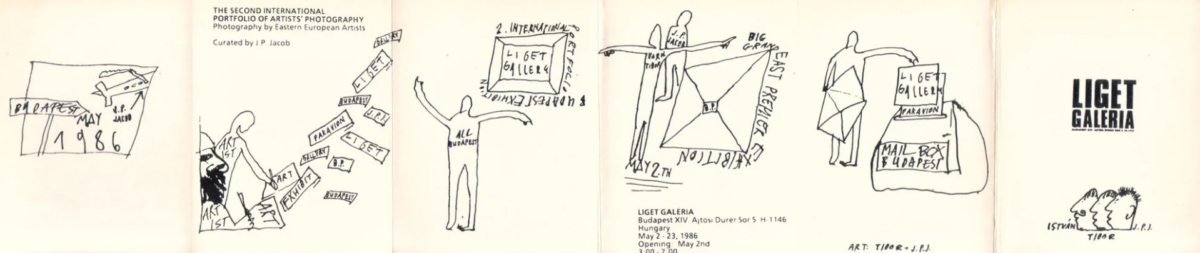

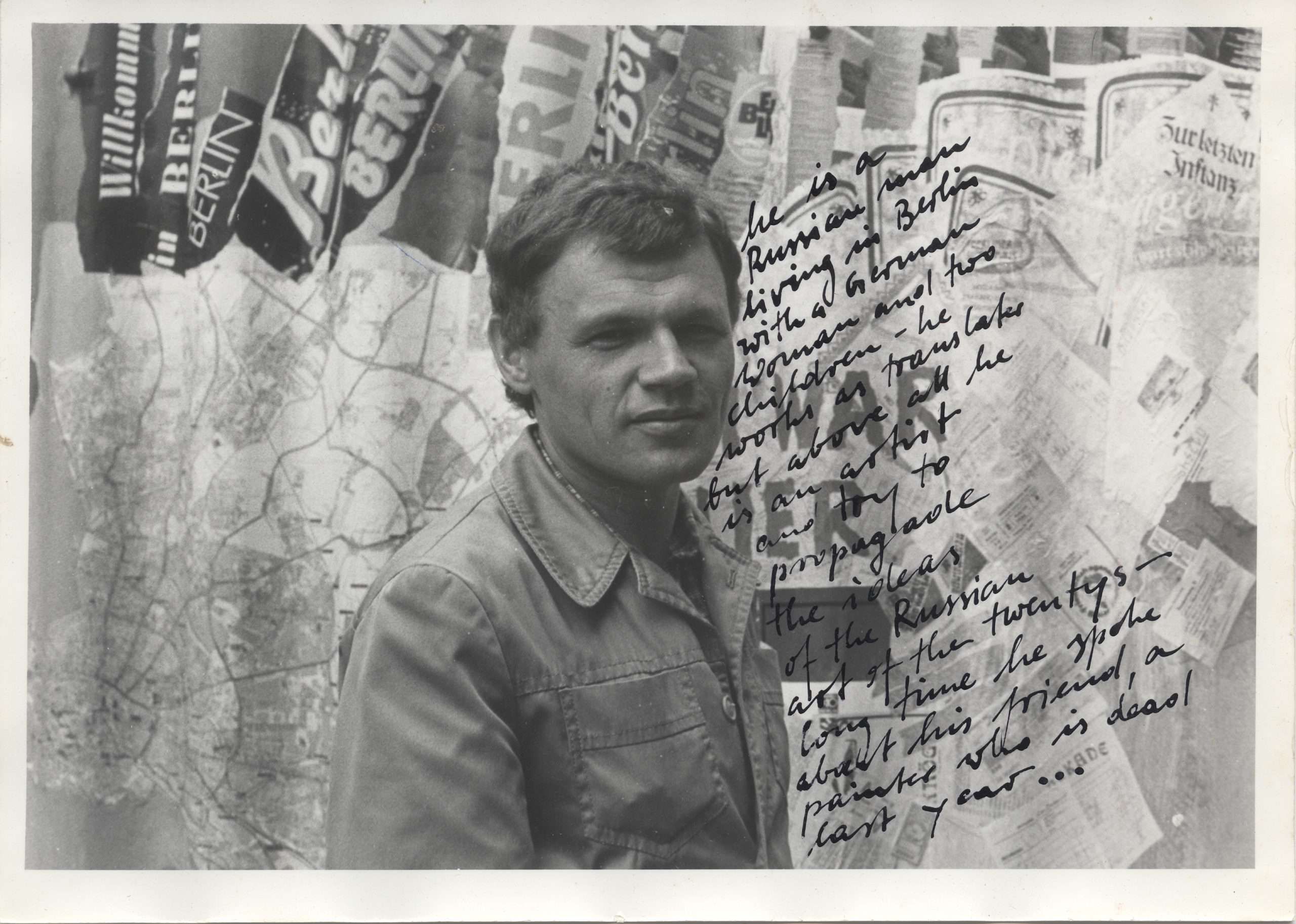

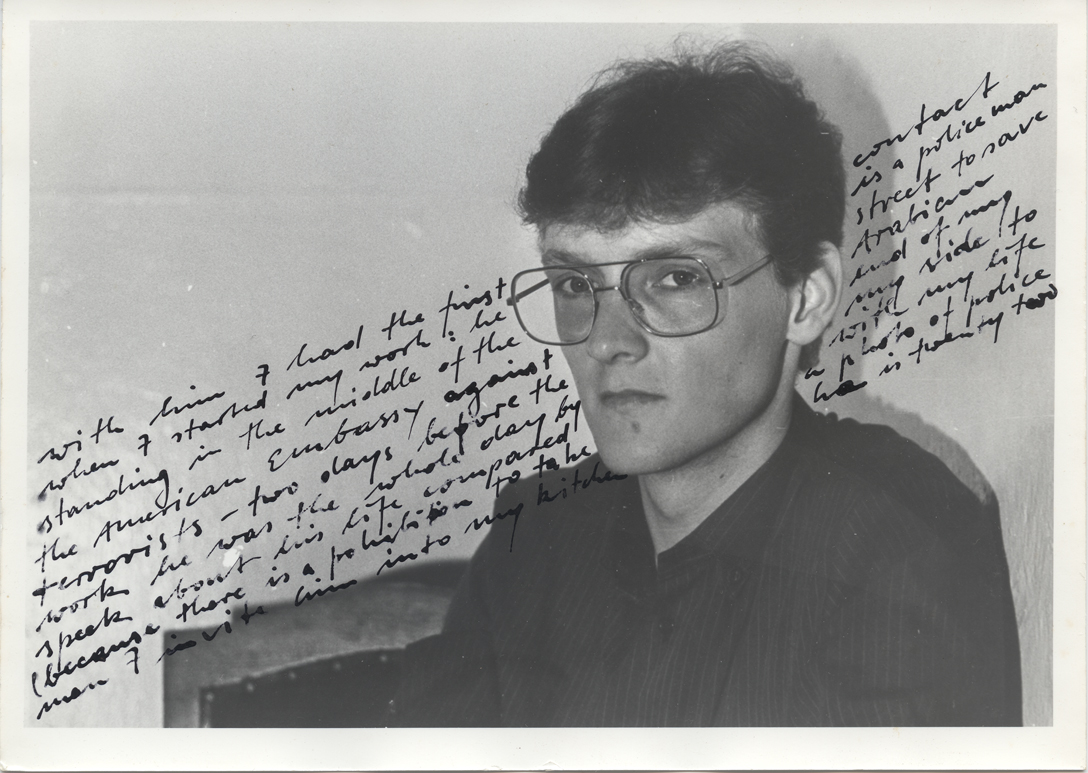

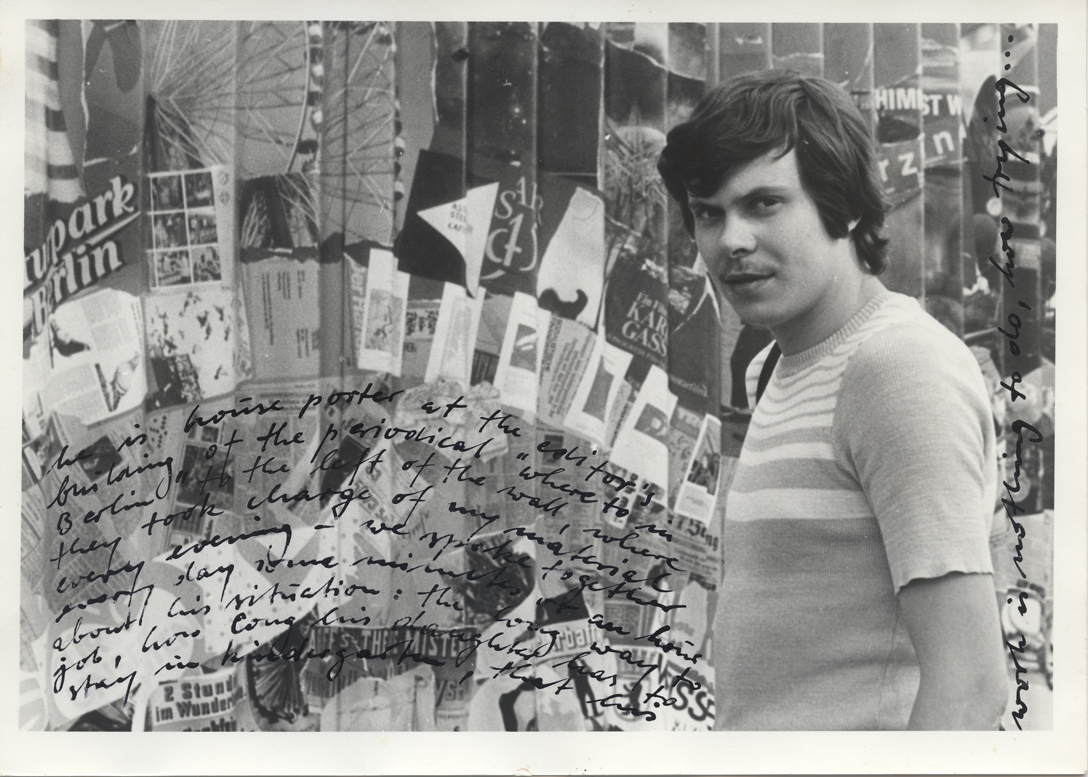

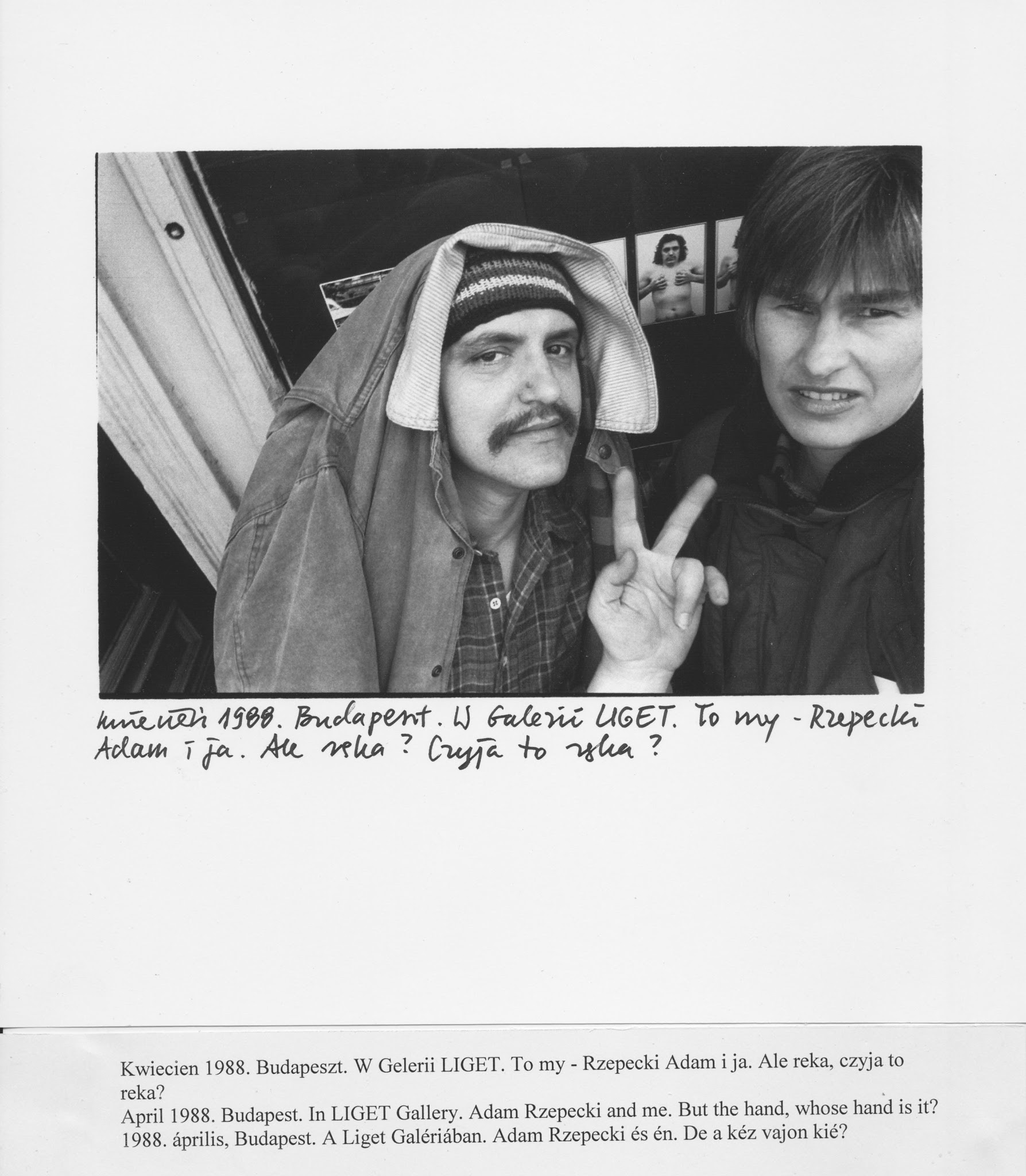

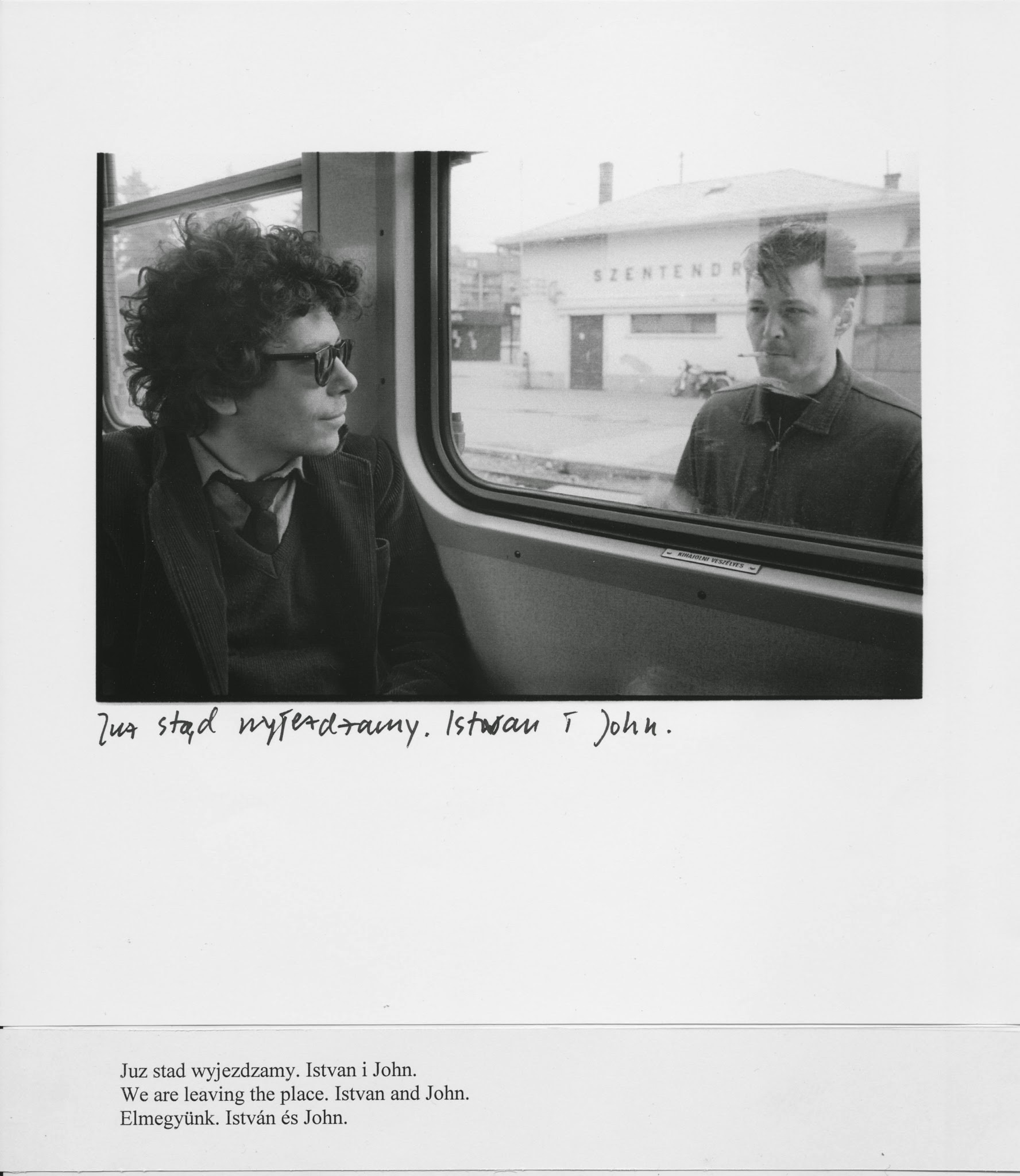

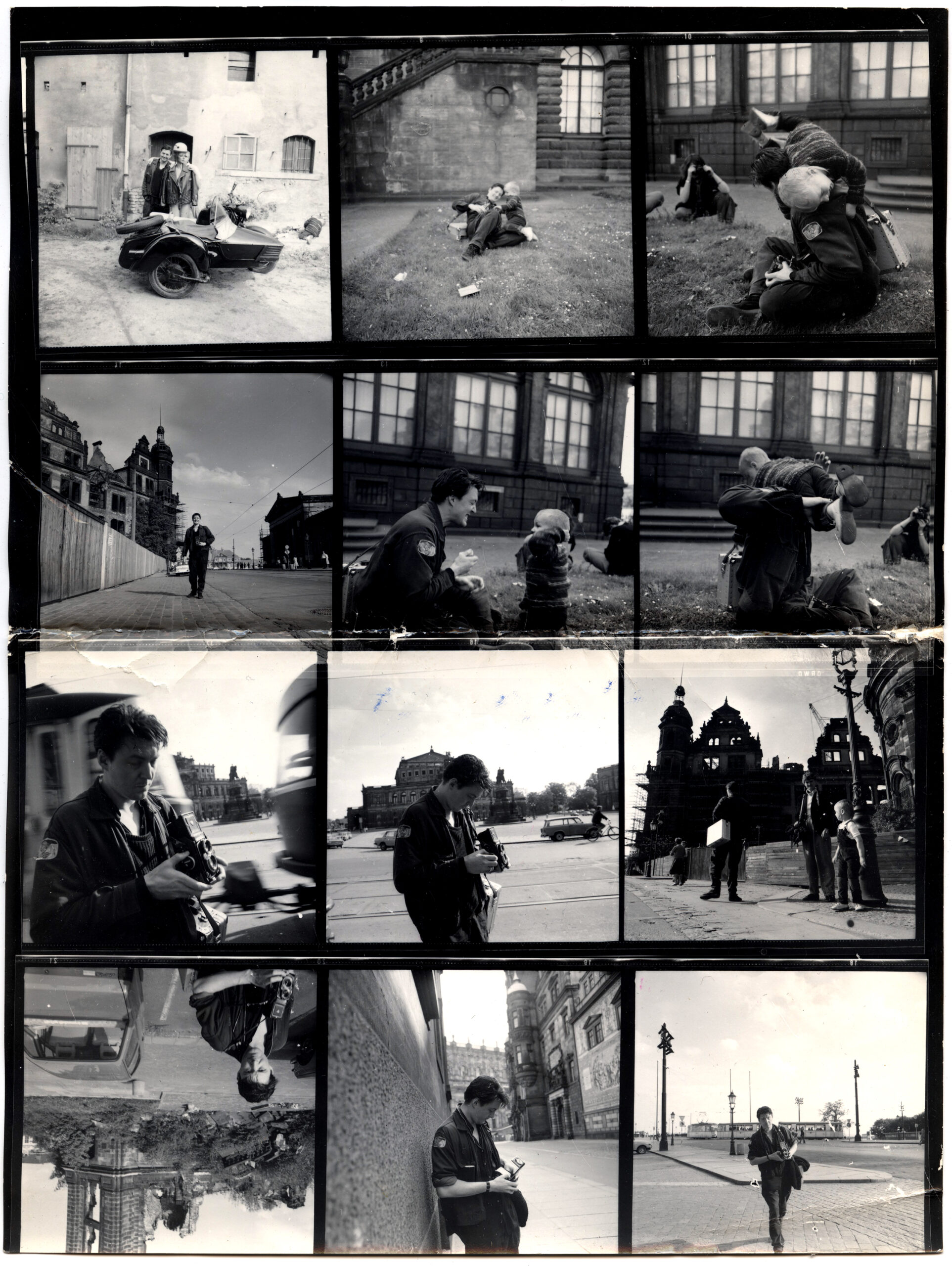

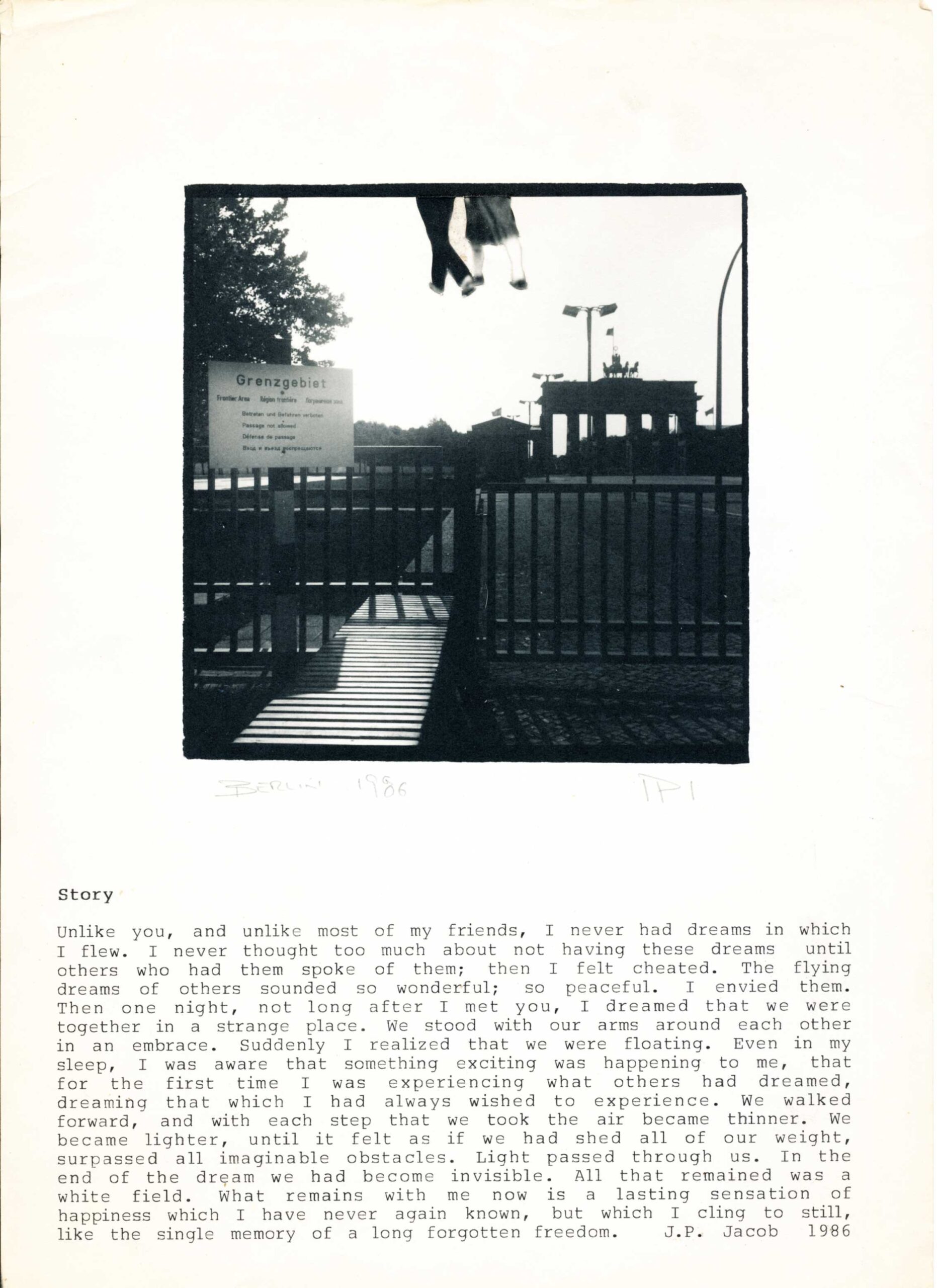

Jacob travelled to Eastern Europe for the first time in April 1986, to exhibit the Second Portfolio at the Liget Galeria in Budapest. He traveled by rail for just under two months, from Belgrade and Novi Sad to Budapest, then going north via Bratislava, Prague, Dresden, Karl Marx Stadt, and Berlin, all the way to Elblag, returning to Budapest via Warsaw, Lodz, and Katowice. Along the way he visited mail artists and photographers, and he presented a slide lecture entitled Photography from the US, USSR, and Eastern Europe, showcasing his own work and that of colleagues in the US alongside Soviet and Eastern European photography received for the Portfolio project. Venues included the Liget Galeria and, in Poland, where he was registered by his hosts as a “Cultural Delegate” from the US, Praconia Dziekanka, Warsaw, and Attic Gallery, Lodz. In Czechoslovakia and the GDR he presented in private homes.

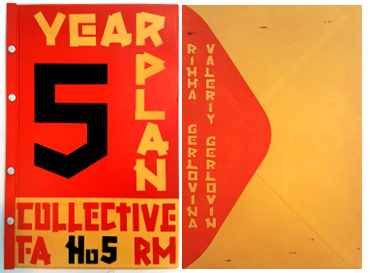

Jacob’s initial appeal for support from the Soros Foundation was declined. A representative of the Foundation explained that it supported him in principle, but the artists he was working with were too risky for it to be associated with. After an introduction from Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin to Meda Mládková, Jacob visited her in Washington, DC, and presented the Second Portfolio to her. She spoke personally with George Soros, and the Foundation subsequently awarded Jacob the first of several round-trip travel grants. This was hugely consequential. With ongoing support from the Soros Foundation from 1986 through 1990, Jacob traveled twice annually to Eastern Europe and the USSR, each visit lasting eight or more weeks. He travelled as a tourist rather than the designated representative of an institution, staying in private homes. He was thus free from the restrictions on cultural delegates working for arts institutions, which would have limited his meetings to officially sanctioned artists. Unable to travel to some countries without control, Jacob opted not to work there, focusing instead on those where he could move more or less freely. The exception was the USSR, where Jacob travelled with a tourist visa but was not free to stay in private homes.

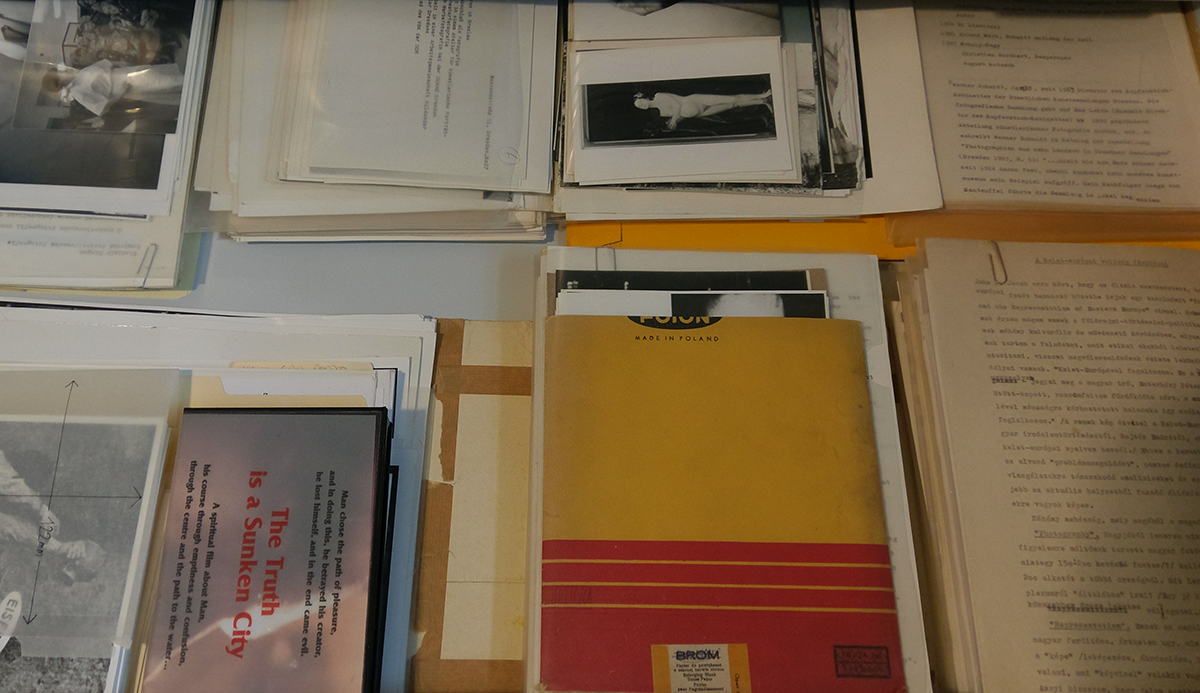

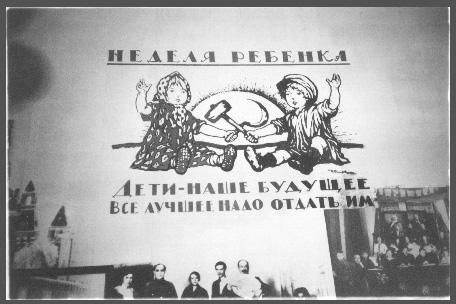

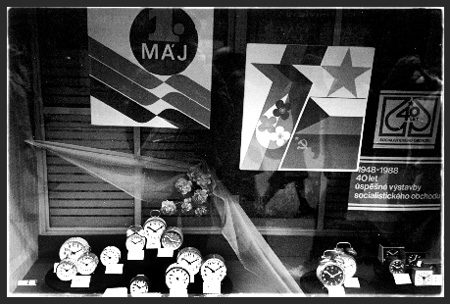

At each stop, Jacob was given photographs for the Second Portfolio project, and he collected ephemera and printed matter; books, exhibition catalogs, posters, brochures, and samizdat documenting a wide range of photographic activities. In contrast with other kinds of cultural production in Eastern Europe, photographs were not considered artworks and had no legal status or financial value. There was little risk in giving or receiving photographs, though their later use by Jacob resulted in political difficulties for some photographers. To counter this, all Jacob’s pre-1990 projects were accompanied by a disclaimer that the works presented were from his personal collection, and were exhibited or published without permission. This was a standard precaution of the time, already widely used by mail artists when publishing works received from the USSR and Eastern Europe. It was this grey zone of legality that made possible the presentation of the Second Portfolio in Budapest in 1986, as Jacob’s personal collection. At that time, Várnagy noted that it would be difficult, and possibly illegal, for a pan-Eastern Europe exhibition to be locally organized. Local cultural ministries frowned on East/East and East/West exchanges alike.

With the flexibility of his international air travel covered by the Soros Foundation, Jacob used the postal system to communicate with artists about his projects and the rail system to visit them, receiving and transporting their works back to the US. Jacob also couriered works for some photographers, to Western Europe and to the US. As his visits became more regular, his close contacts in each country collected printed matter for him to pick up at his next visit. Several times he accumulated so much that he had to cross into Western Europe and put it in storage, at Vienna Central Station or in West Berlin, for example, or at Heathrow when en route to the USSR. To do so always put both the artwork and his travel at risk, since it terminated a visa obtained in advance in the US and required him to apply for a new one at the frontier. Nevertheless, his activity seemed to go unnoticed, and he was never denied a visa.

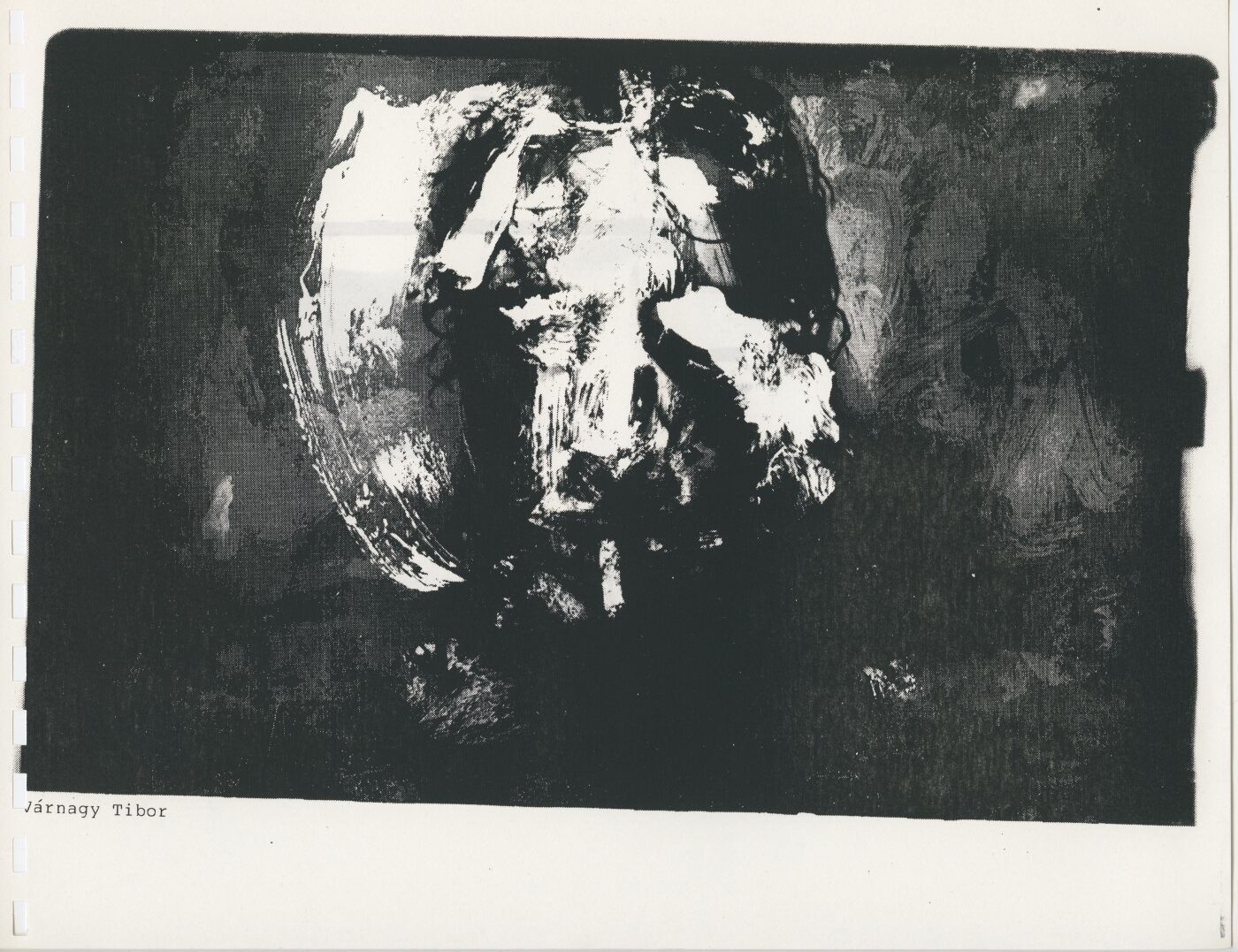

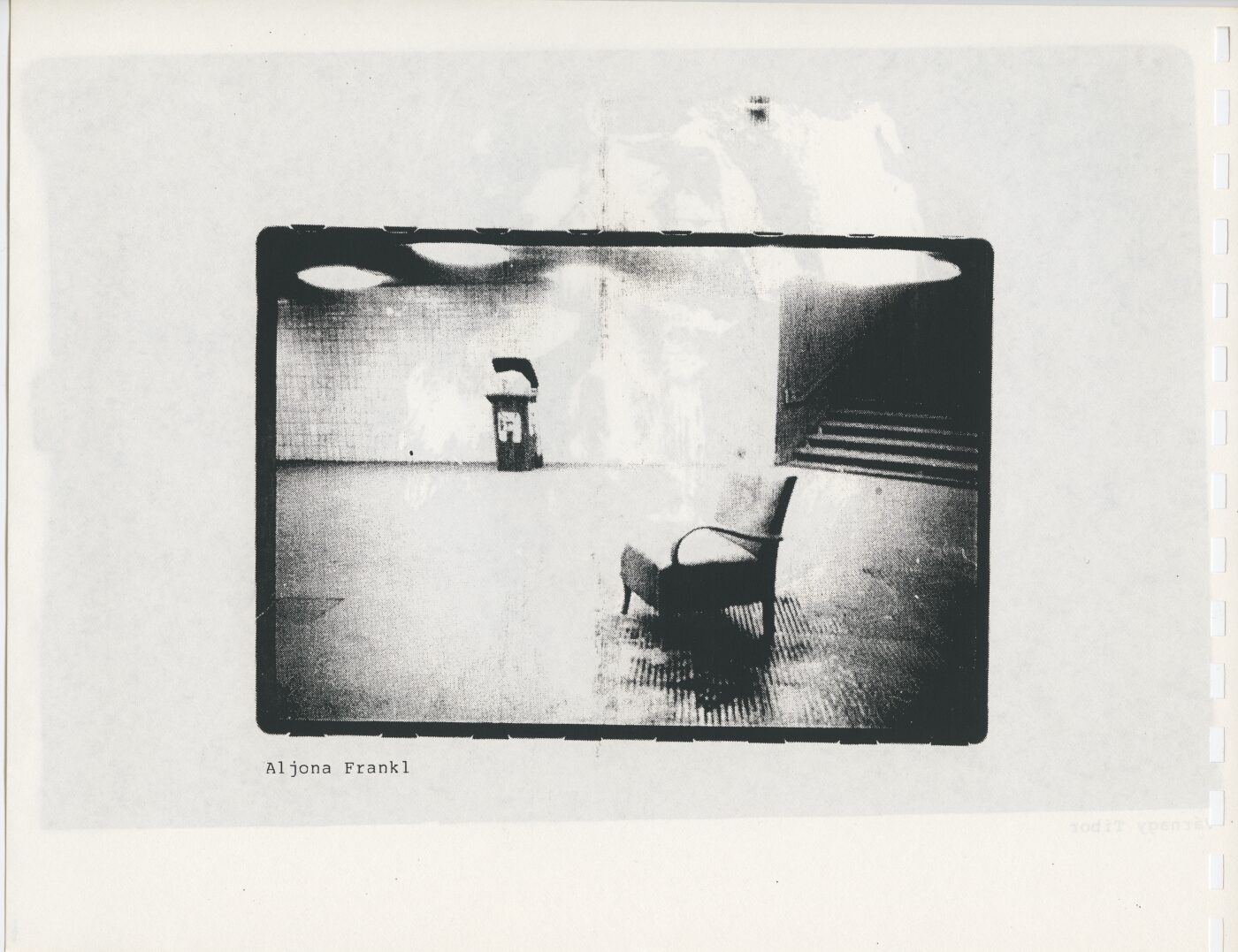

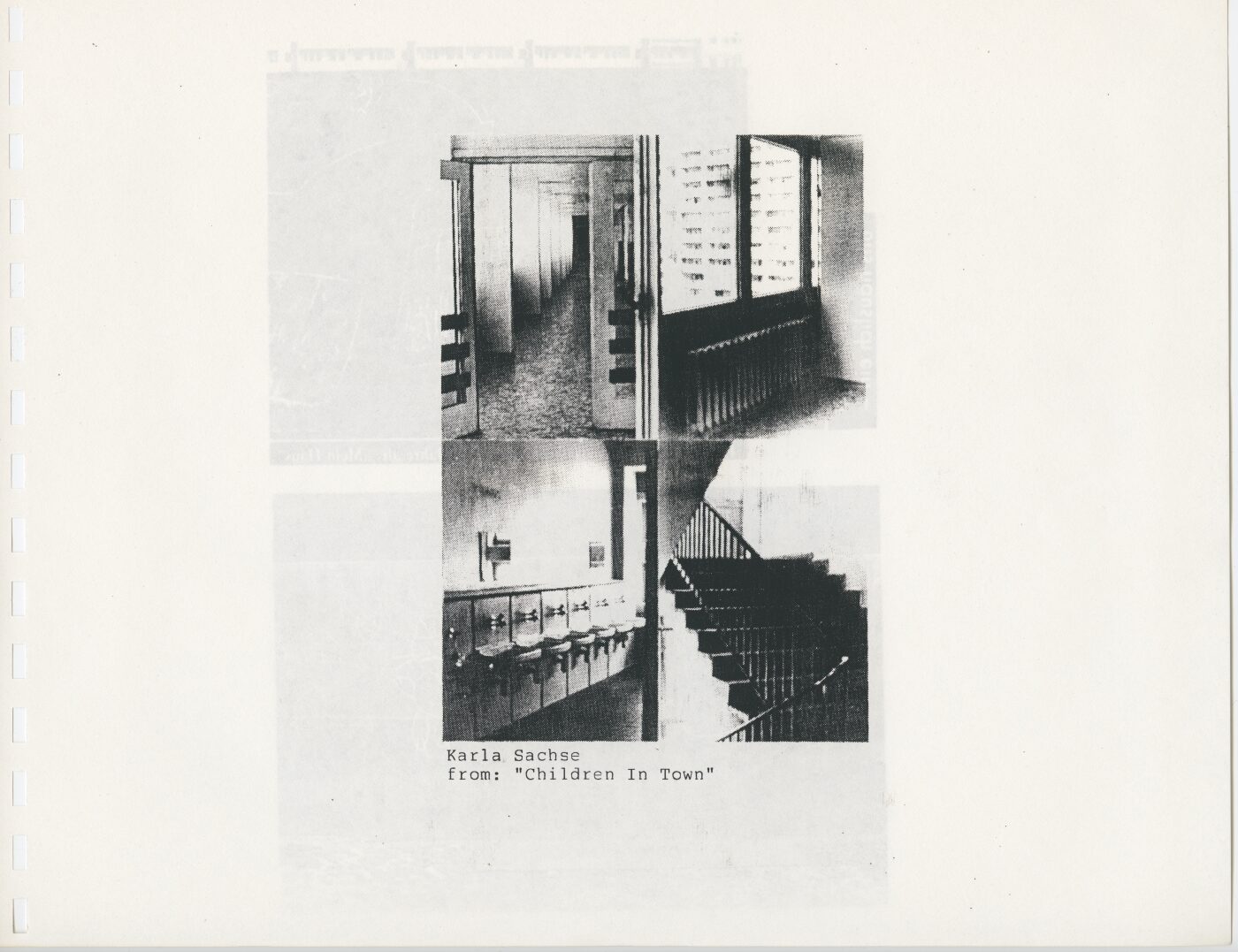

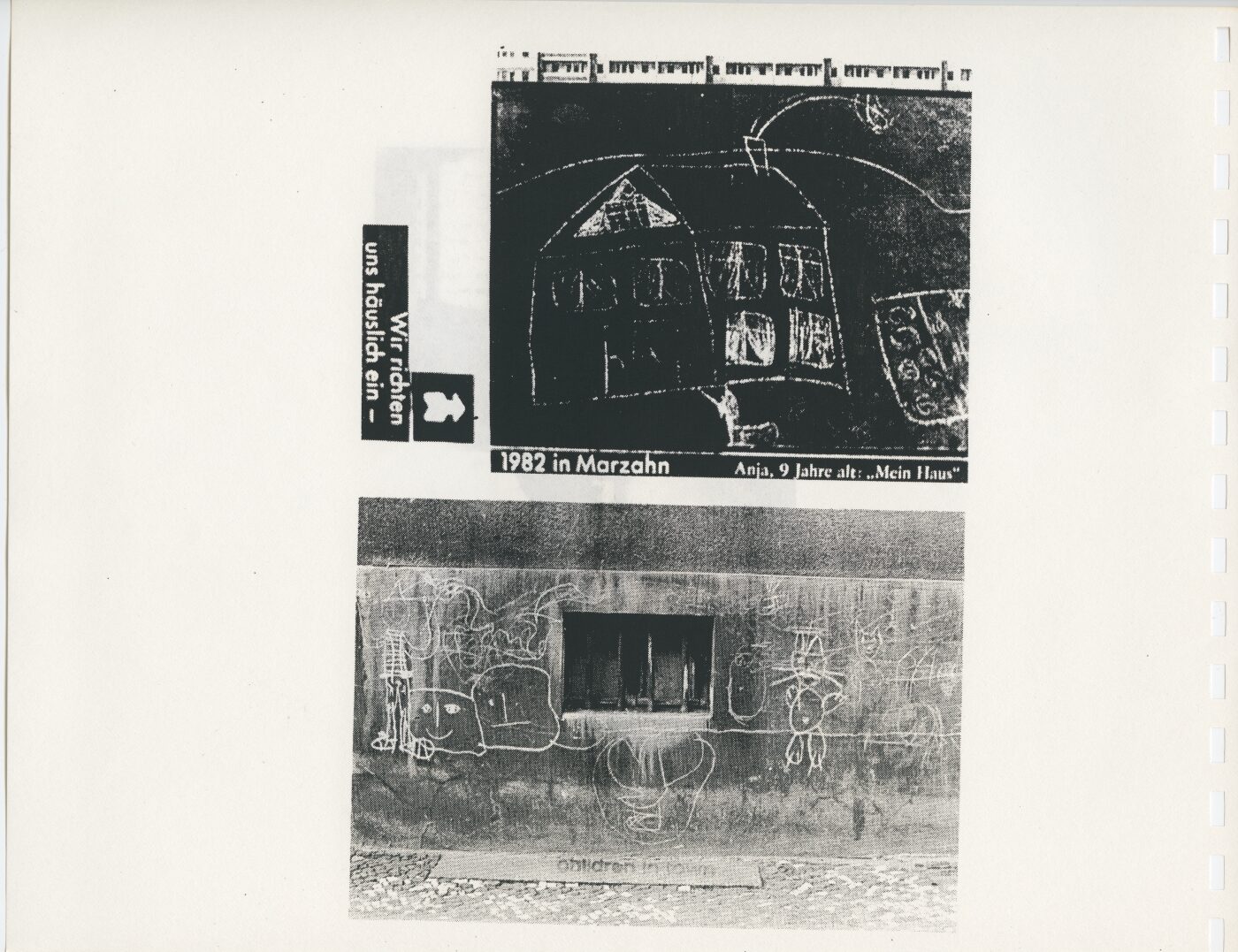

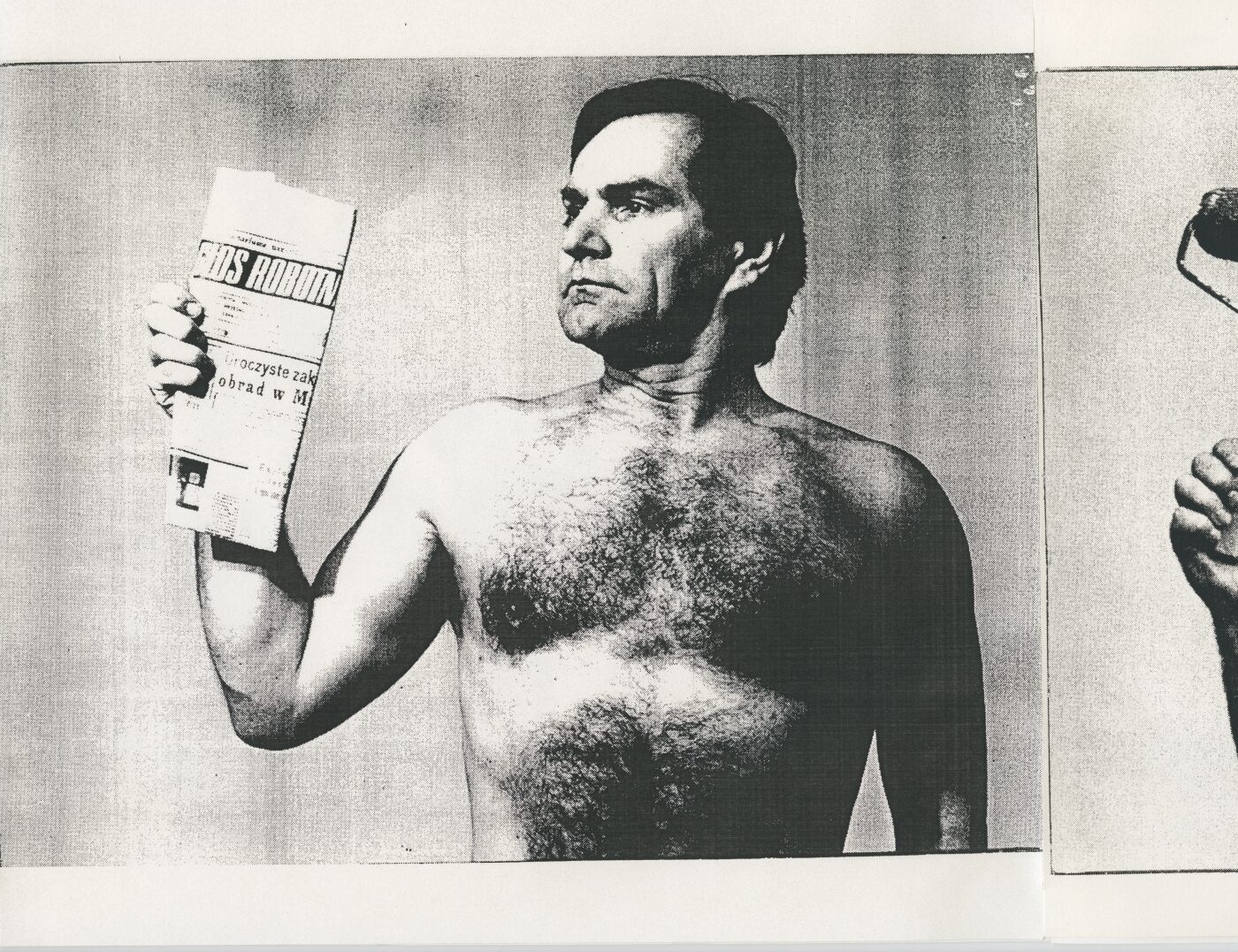

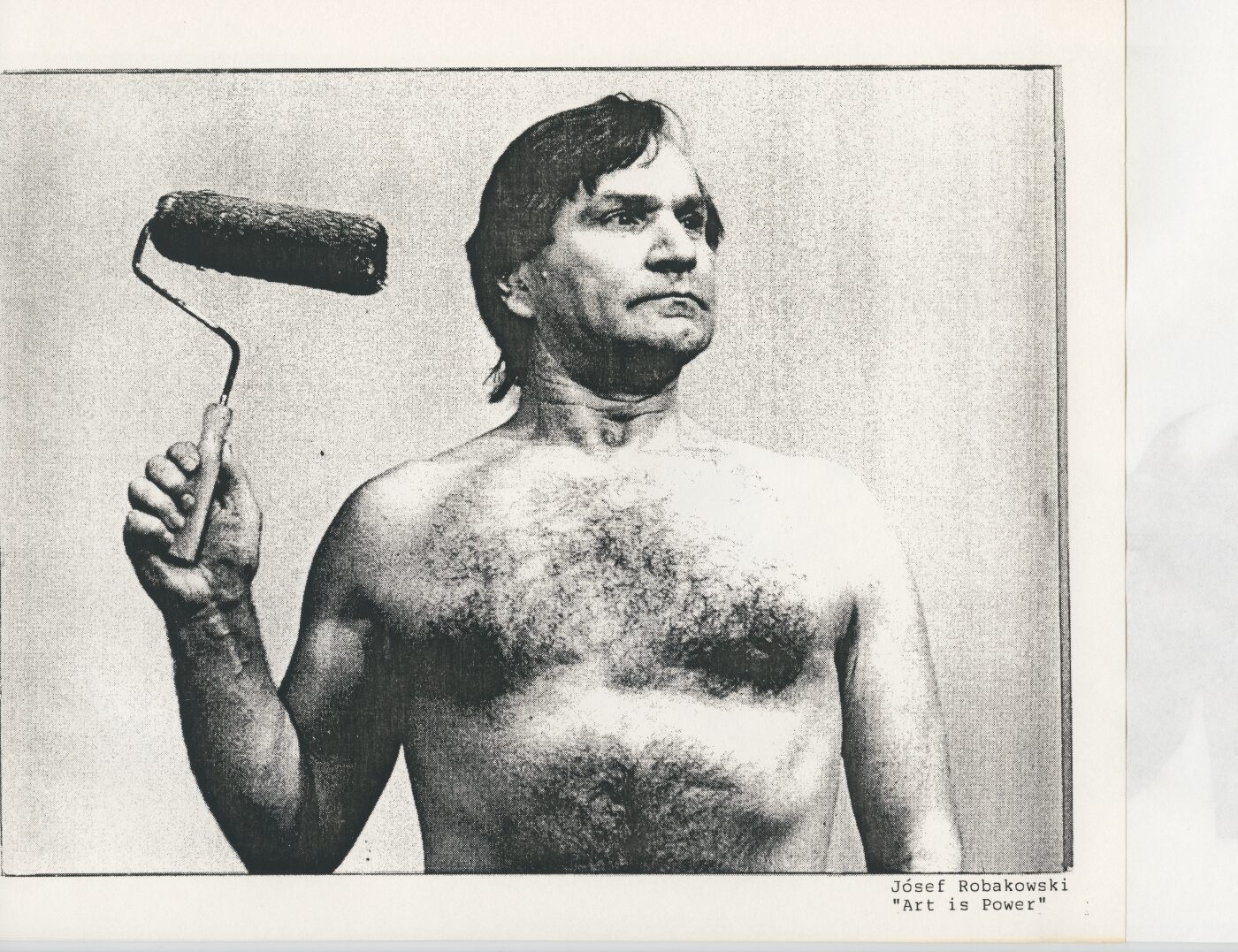

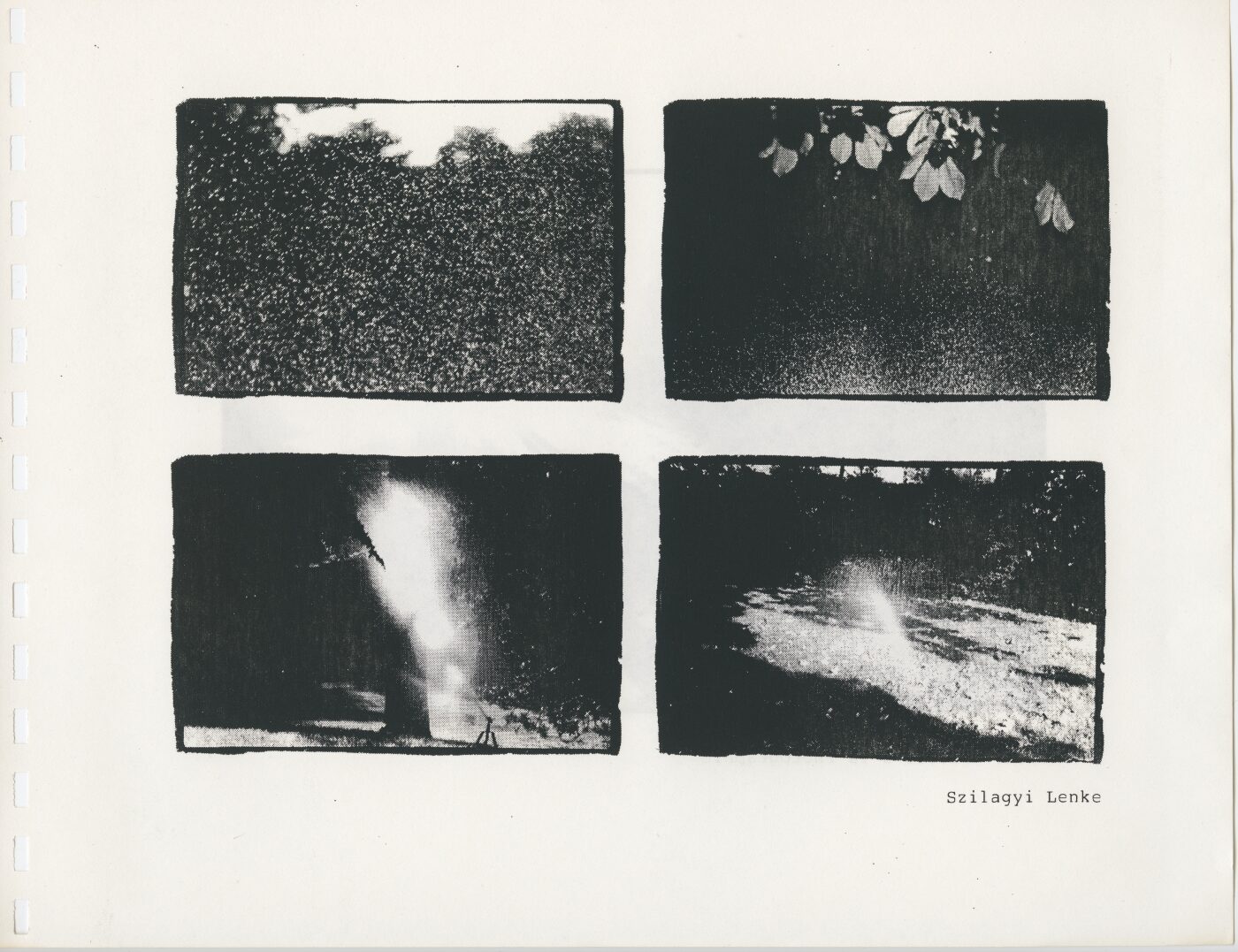

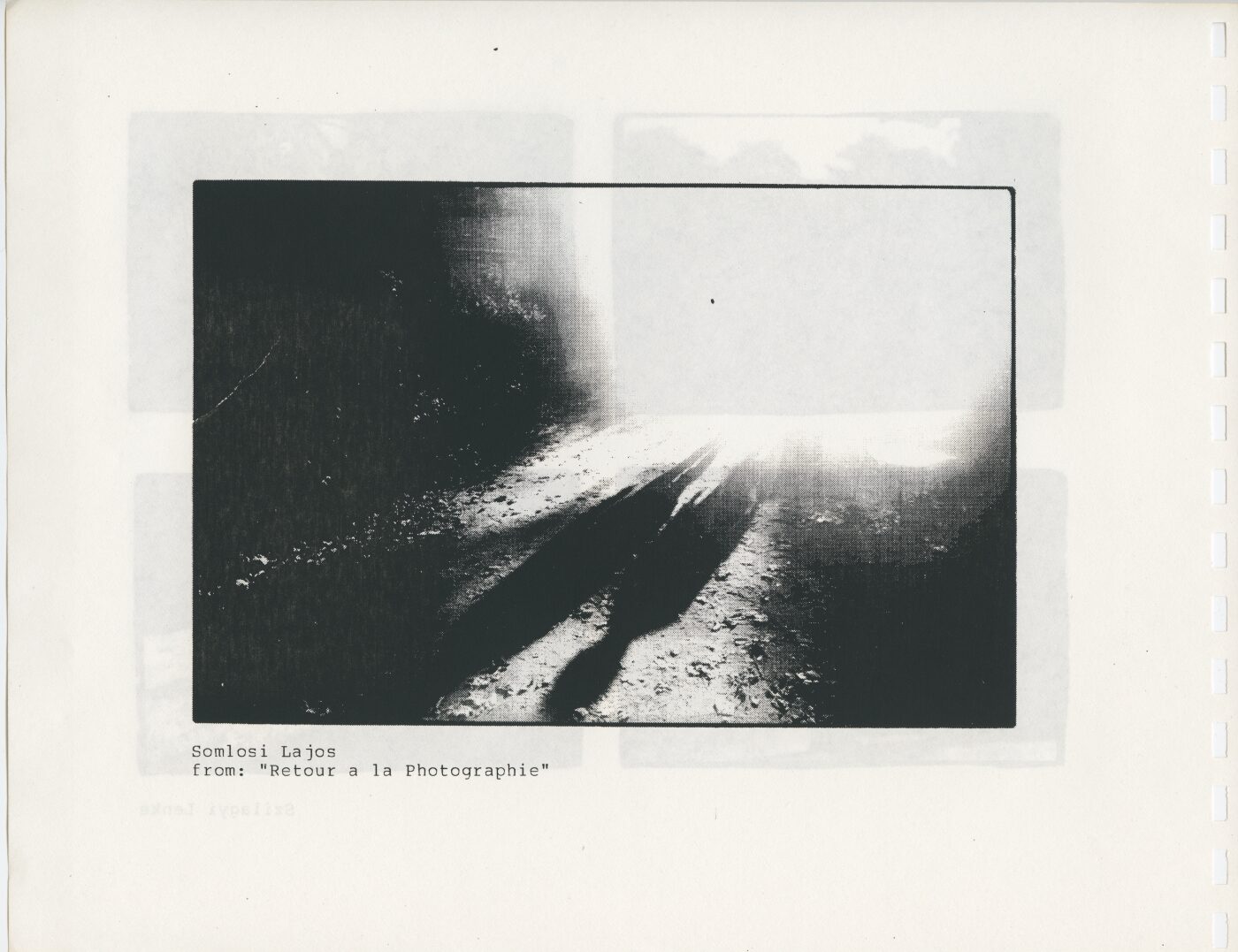

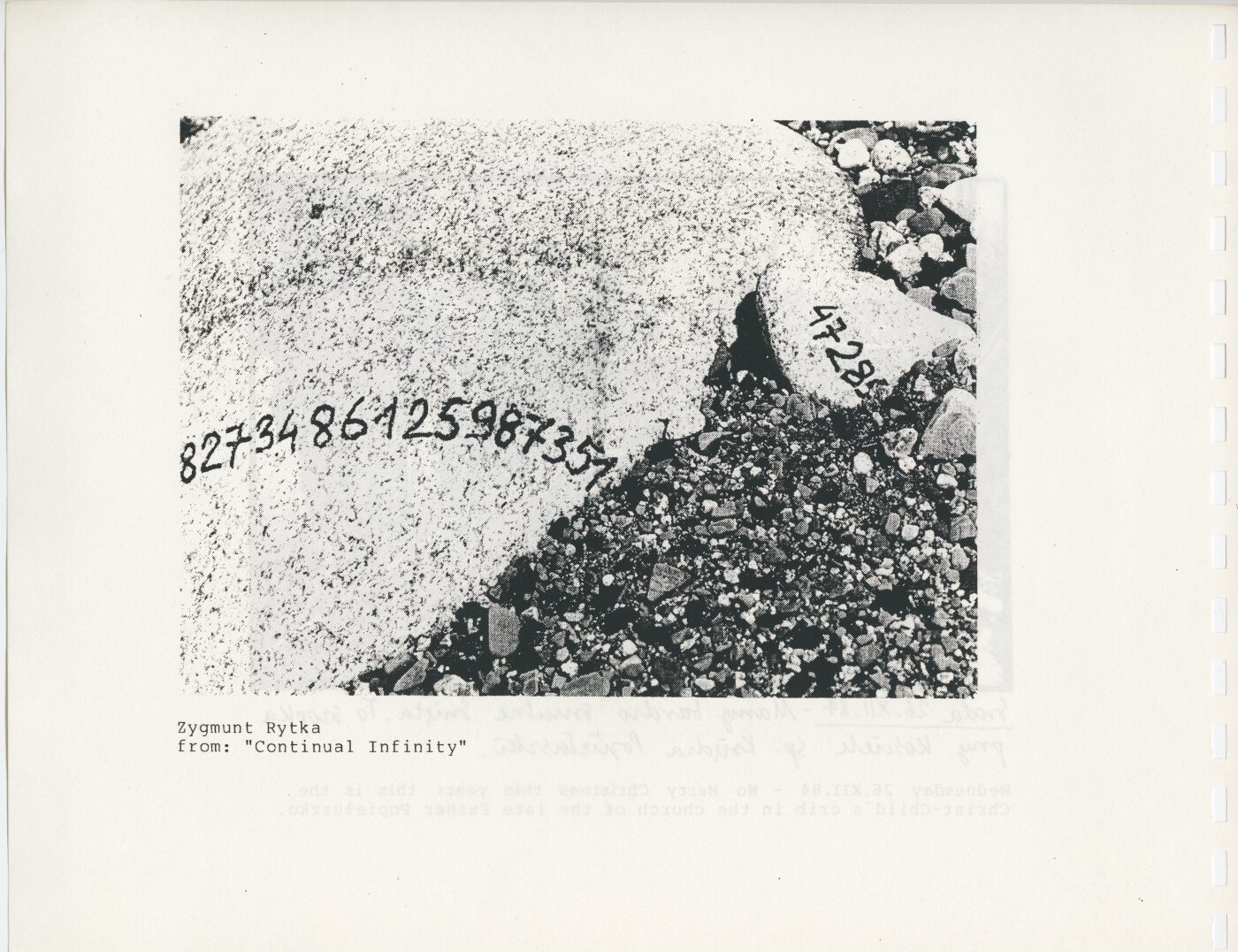

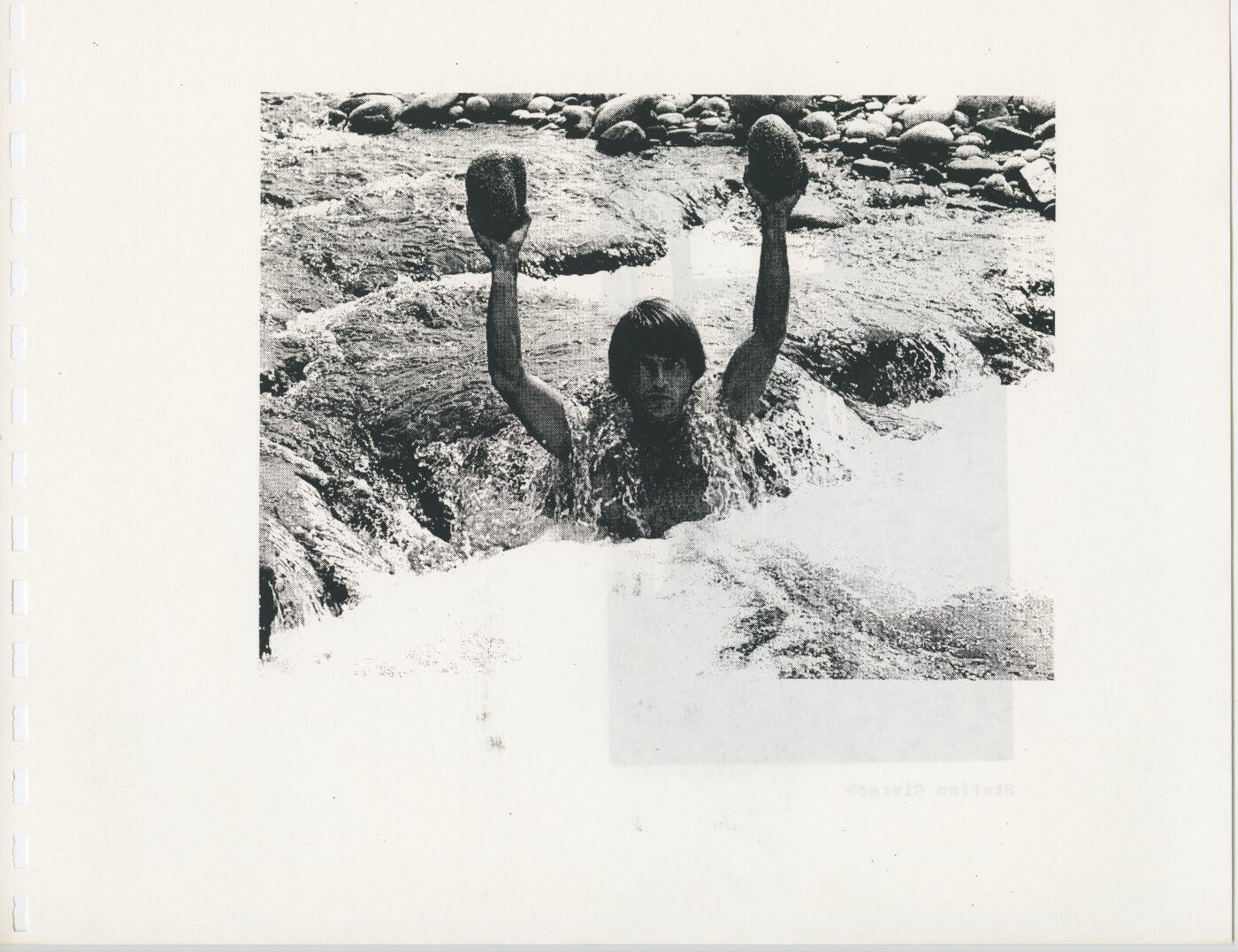

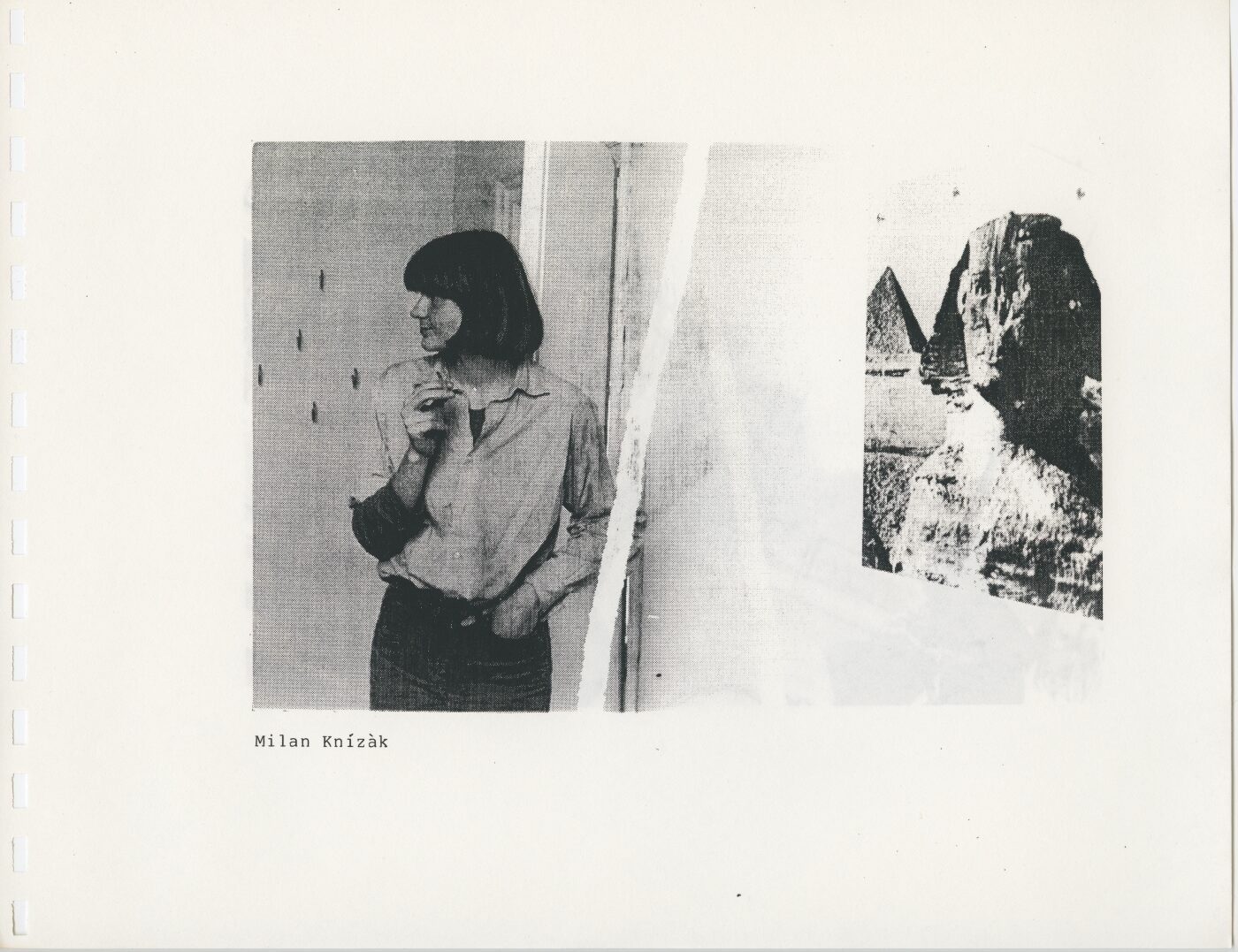

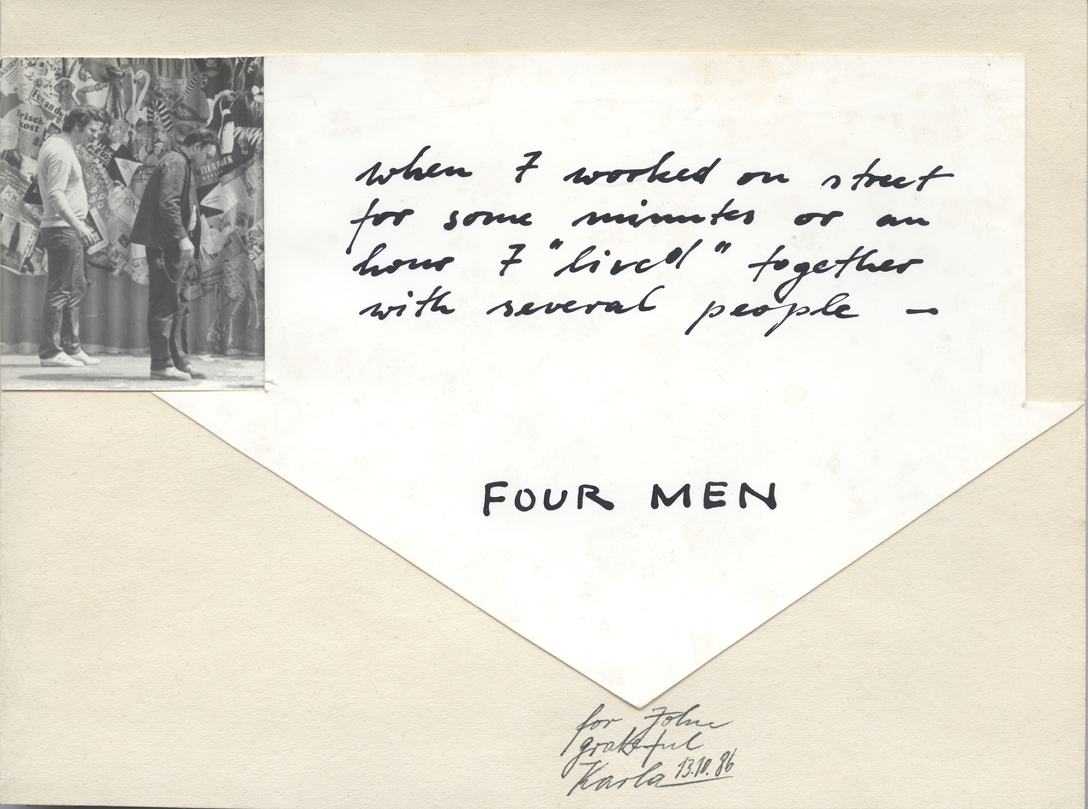

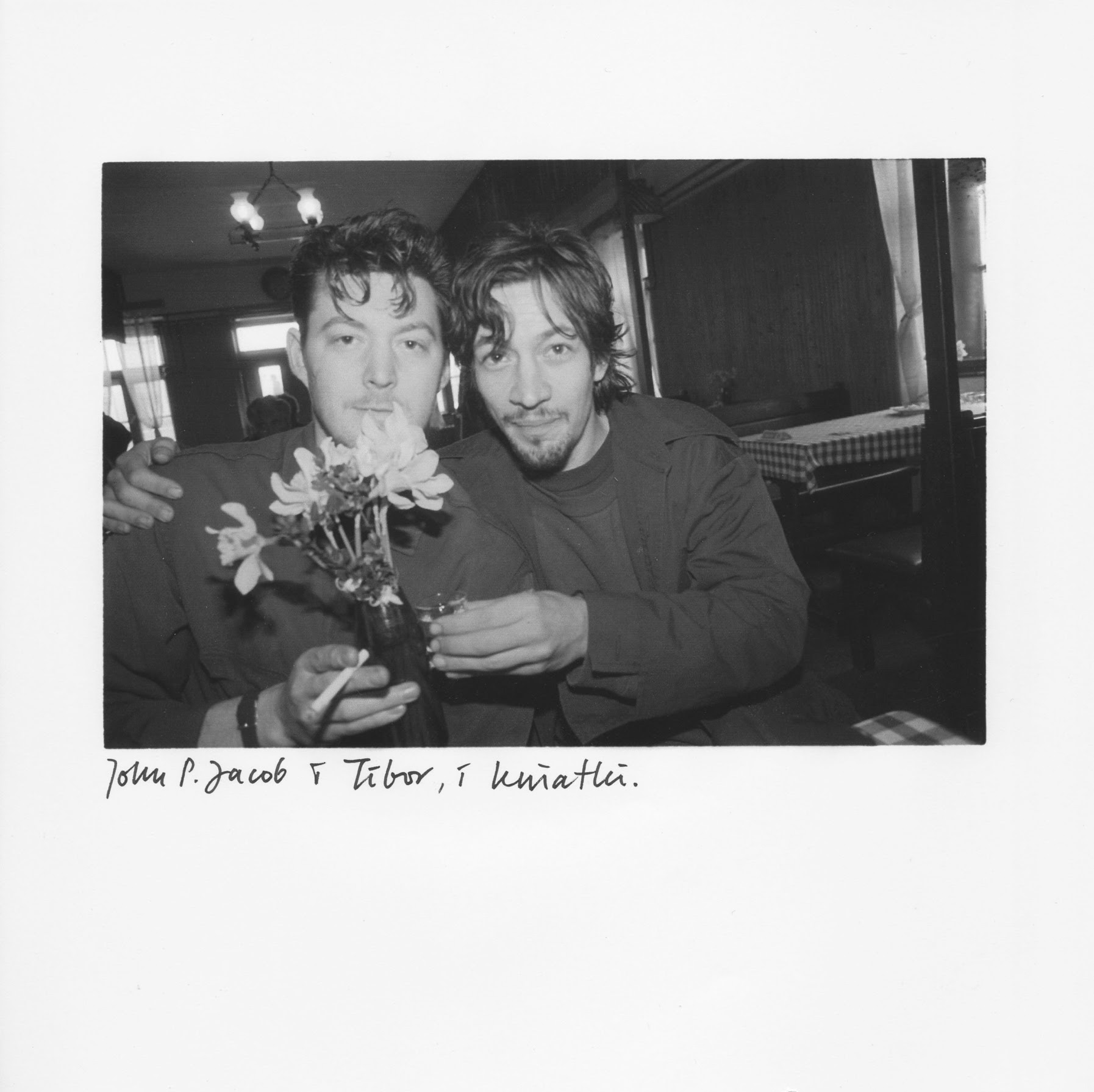

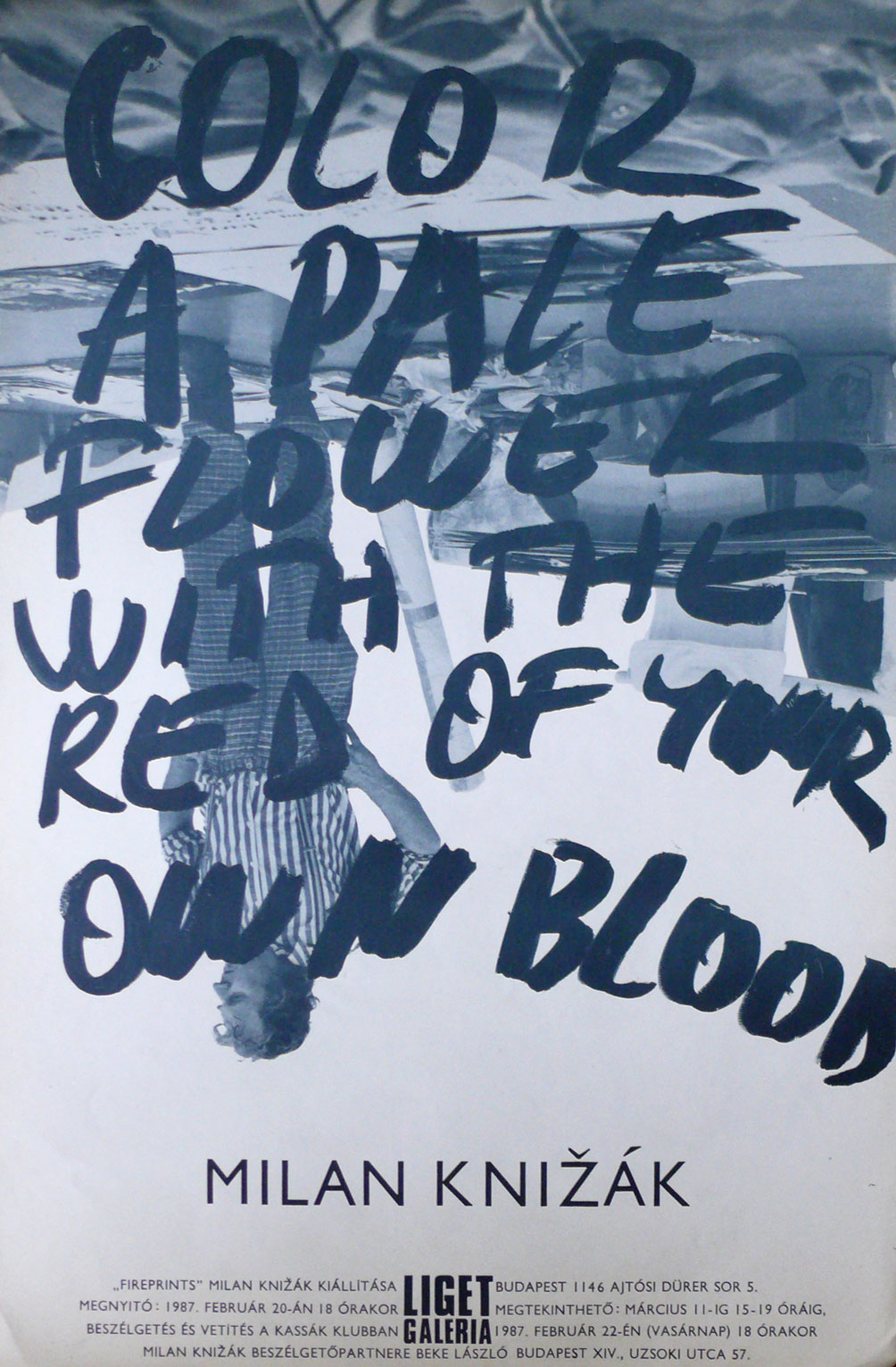

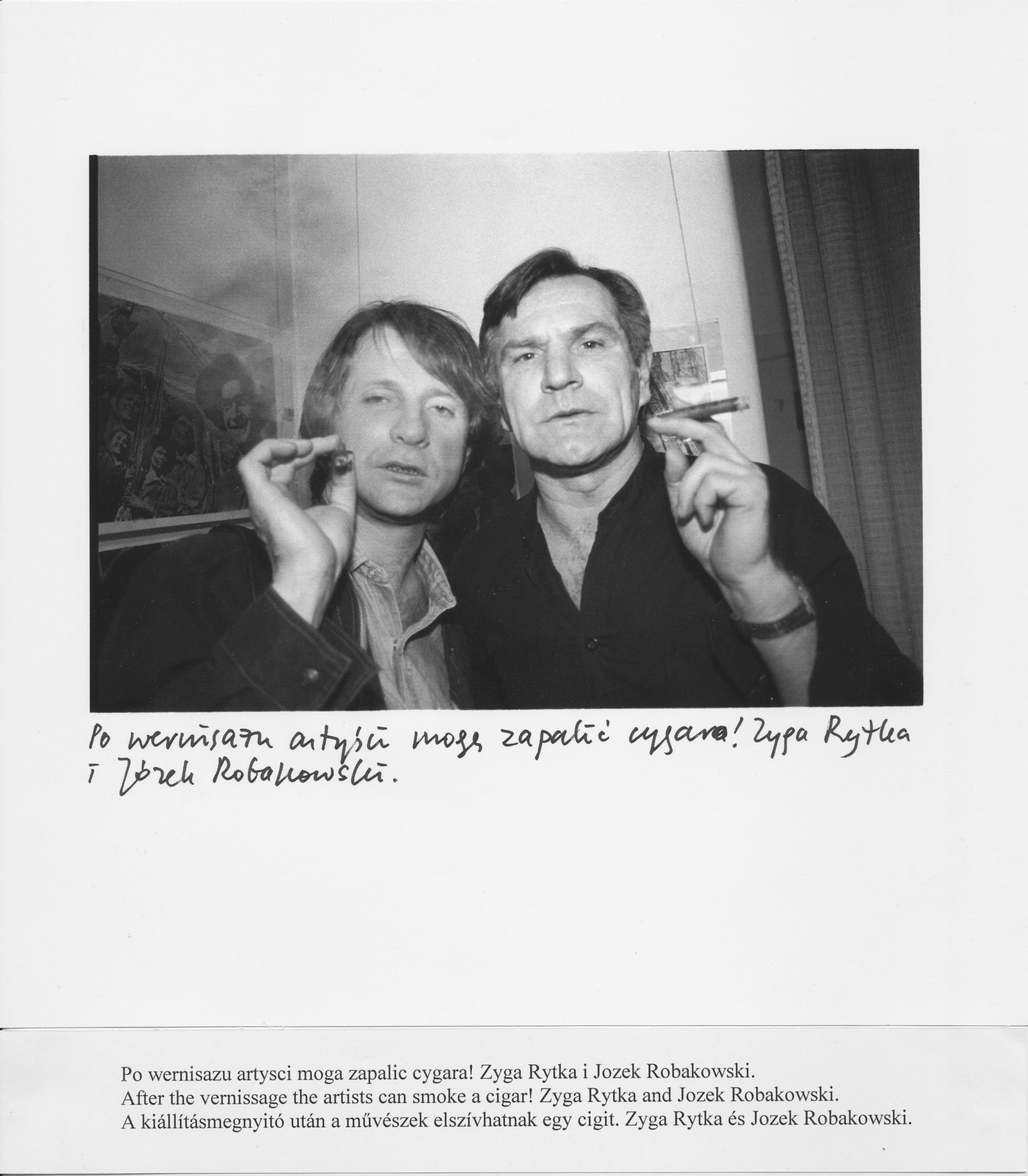

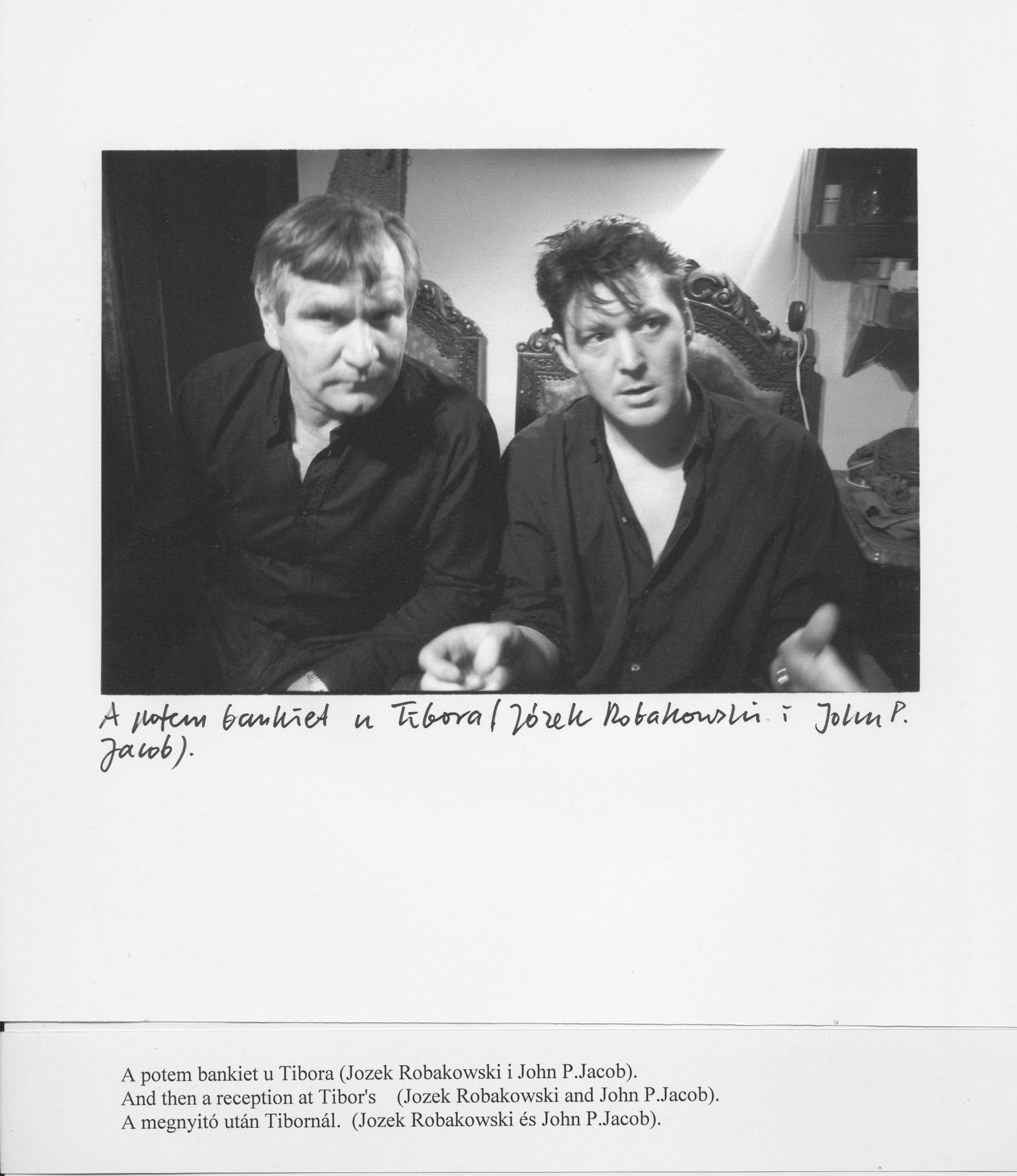

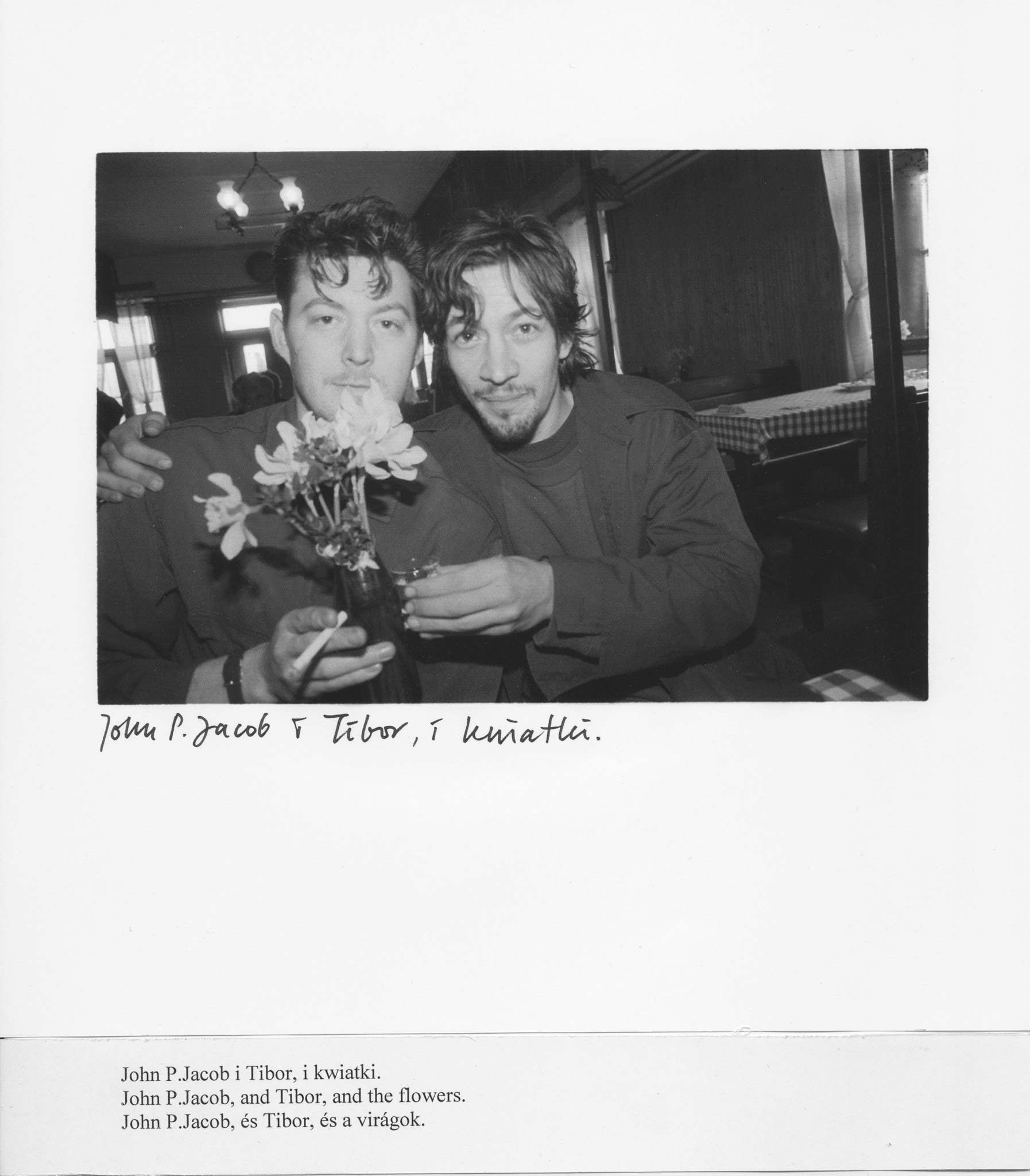

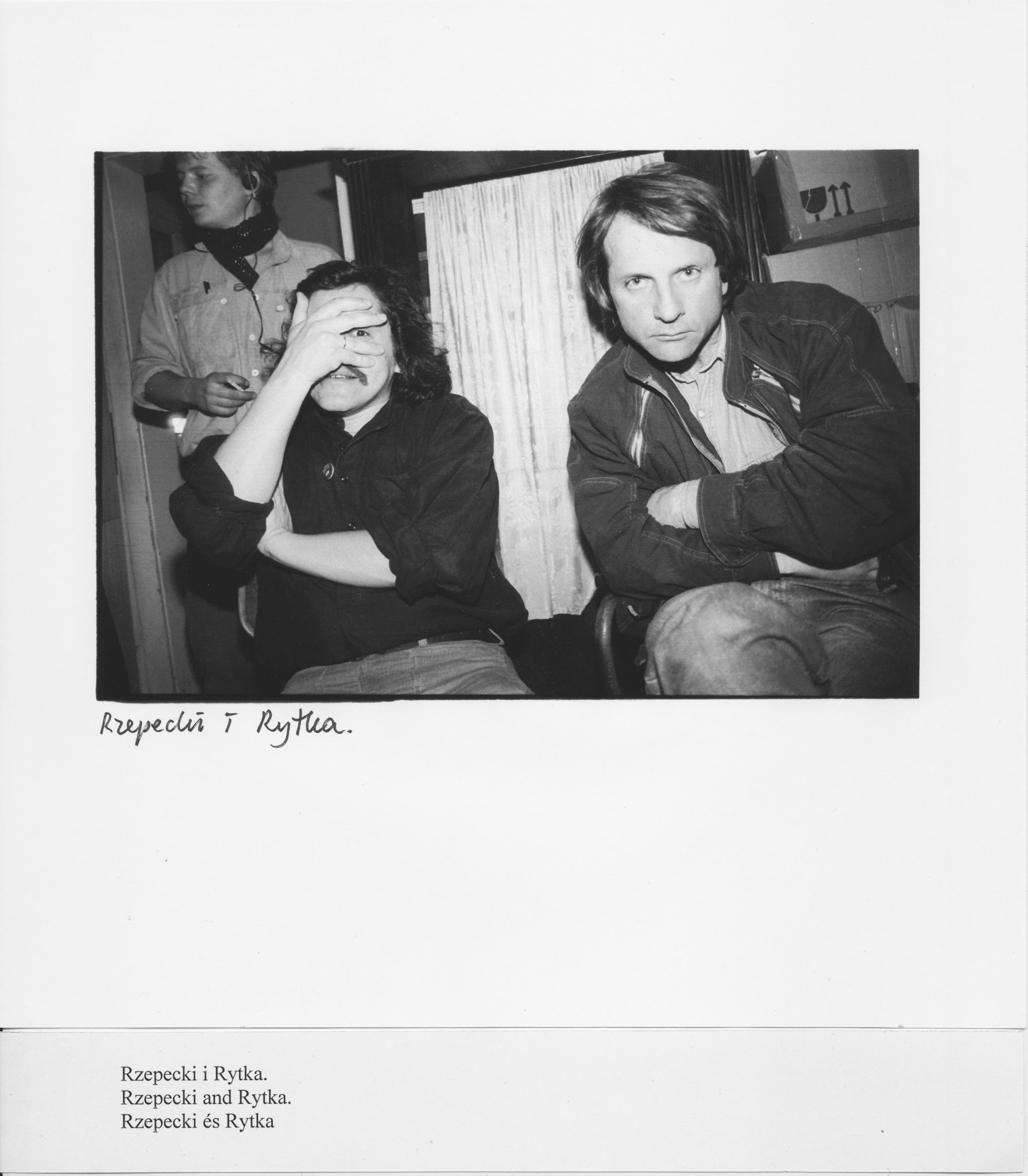

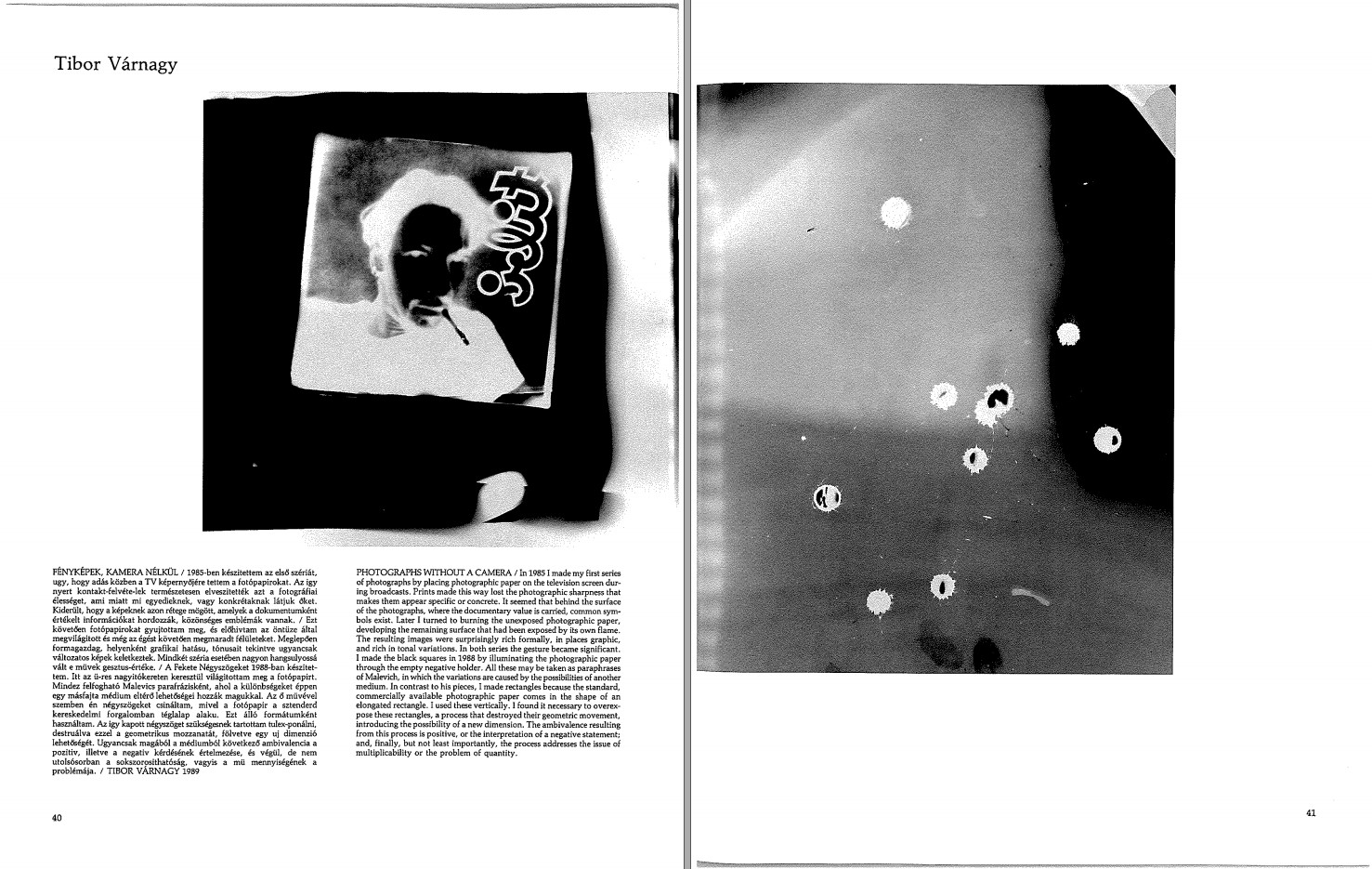

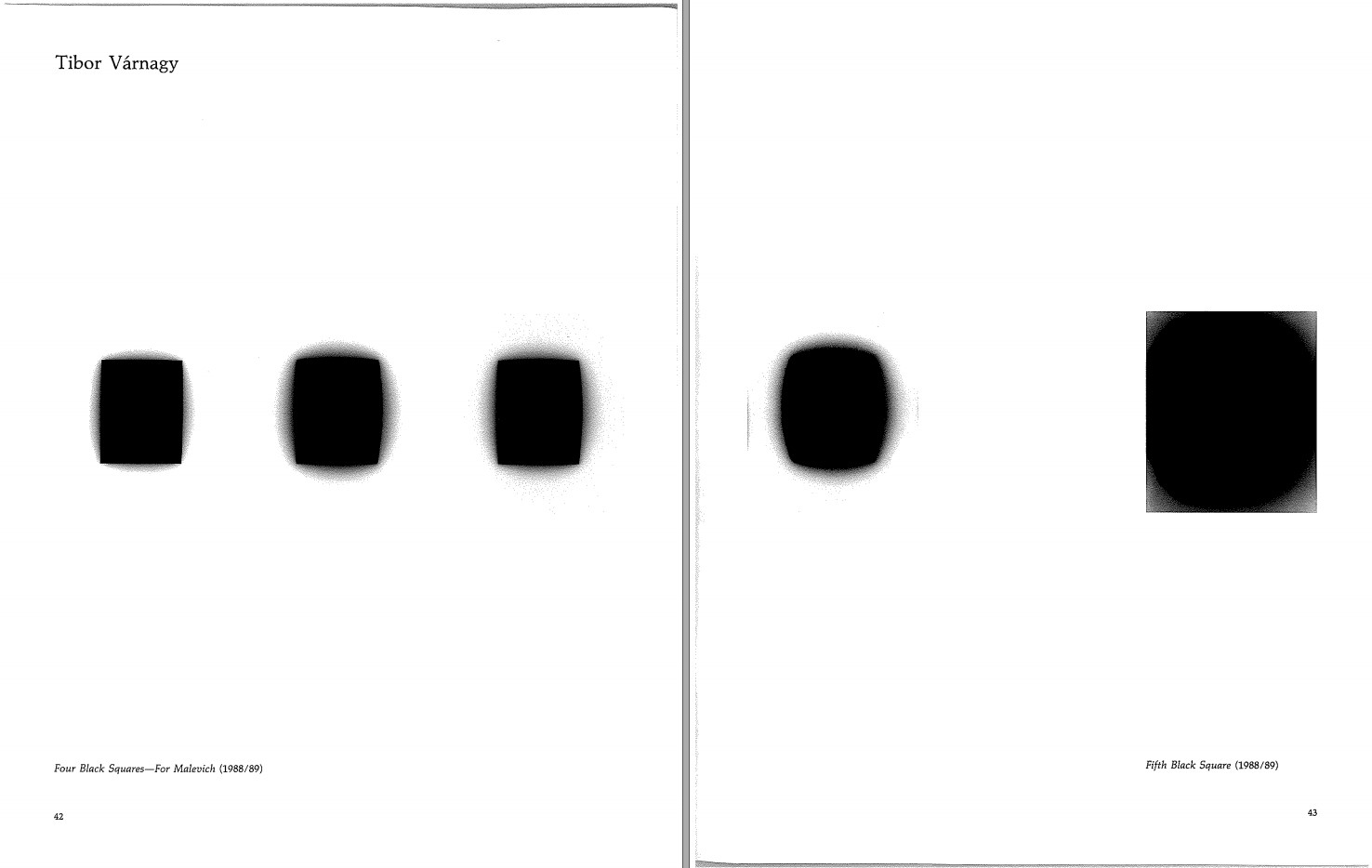

Jacob had one close contact in each country who became a partner in his work: Milan Knizák in Czechoslovakia; Karla Sachse in East Germany; Tibor Várnagy in Hungary; Anna Bohdziewicz in Poland; and Alexei Shulgin in the USSR. Knizák was introduced by Fluxus collector Jean Brown, who also collected Jacob’s work. Sachse and her husband, Joseph Huber, were active mail artists in contact since the early 1980s. Várnagy and Bohdziewicz were early contributors to the Second Portfolio project, and actively promoted it to their networks. Shulgin was introduced to Jacob by photographer Igor Makarevich, who in turn was introduced by Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin. It is important to recall that, especially during his first visits to Eastern Europe, Jacob was speaking artist to artist, and the Portfolio project was intended to produce a series of artist’s books. His development as a curator was an unexpected outcome. Jacob’s contacts were instrumental in helping shape his projects, as a whole, into a document of the wide ranging Eastern European photo-based work of the late 1980s, from documentary (Aljona Frankl, HU; Gundula Schulze, GDR; Zofia Rydet, PL), to film and performance based work (Tibor Hajas, HU; Tomas Ruller, CZ; Jozef Robakowski, PL), to network-based and conceptual photography (Tibor Várnagy, HU; Karla Sachse, GDR; Zygmunt Rytka, PL), etc.

Produce related to Eastern European & Soviet photography, pre-1990:

1983

The First International Portfolio of Artists Photography (artists book, NYC)

1984

East Europe Exhibition (exhibition, No Se No Gallery, NYC)

1985

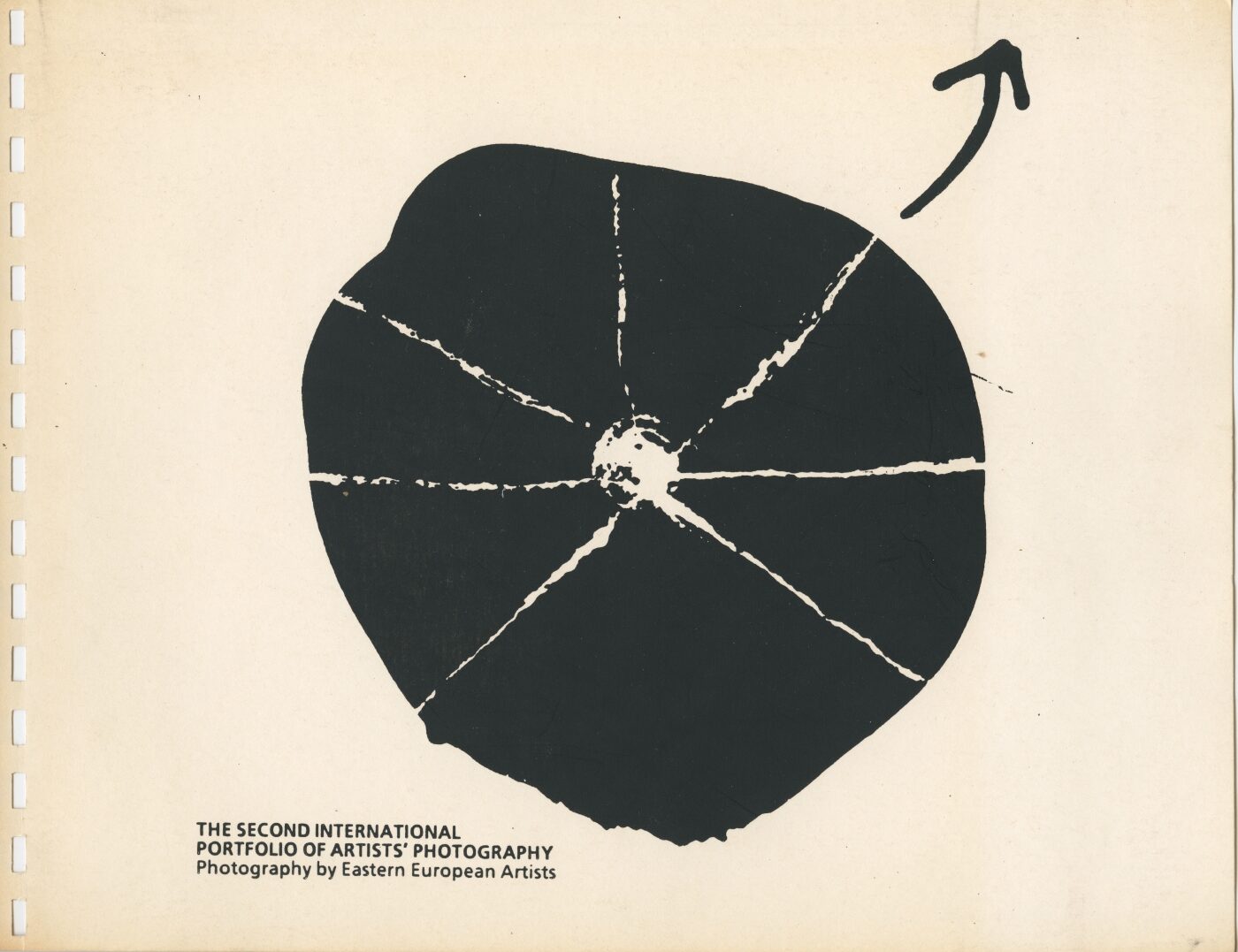

The Second International Portfolio of Artists Photography (NYC Ed, artists book)

Networking in Eastern Europe (letter extracted for a chapter in Chuck Welch’s Networking Currents)

1986

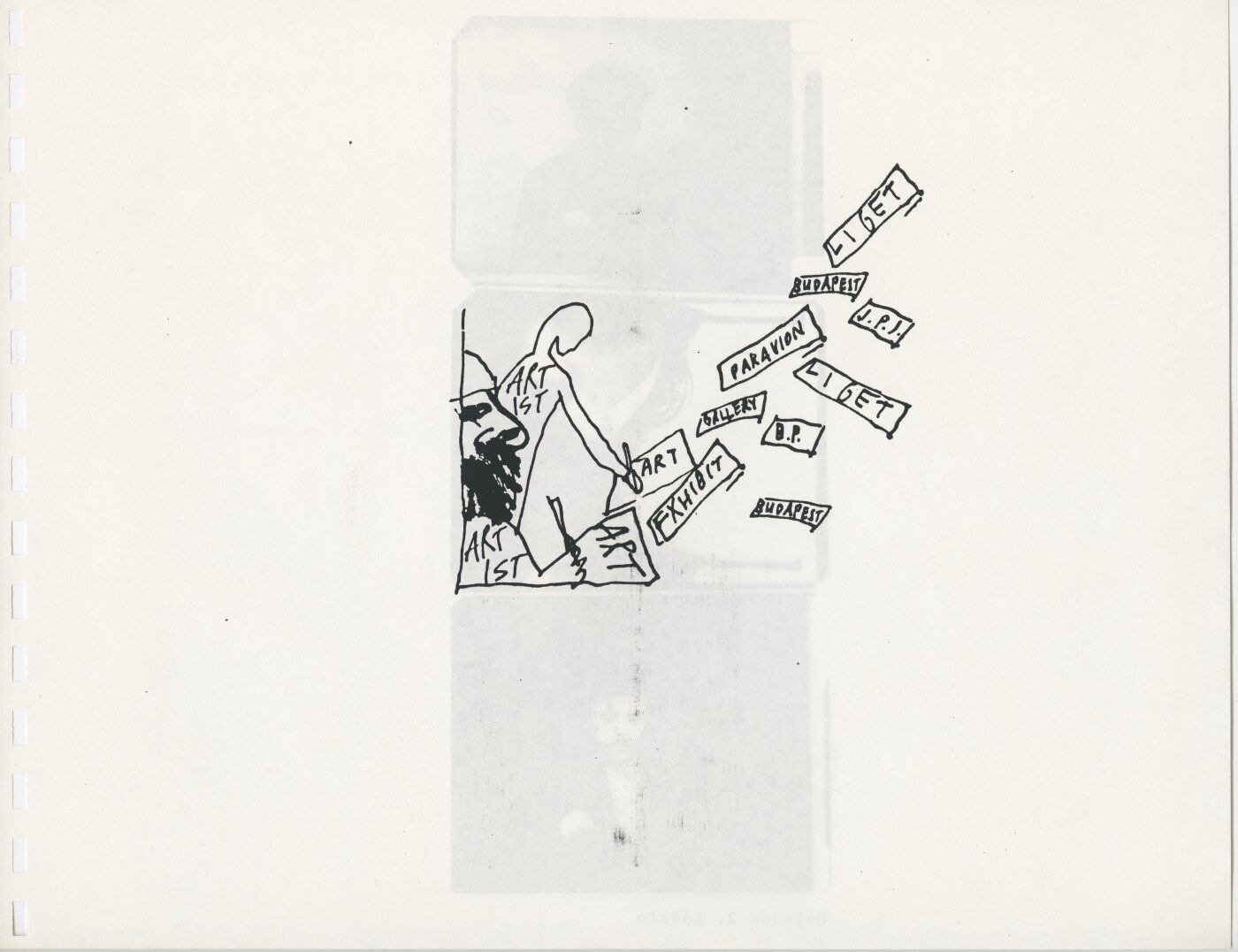

The Second International Portfolio (exhibition, Liget Galeria, Budapest)

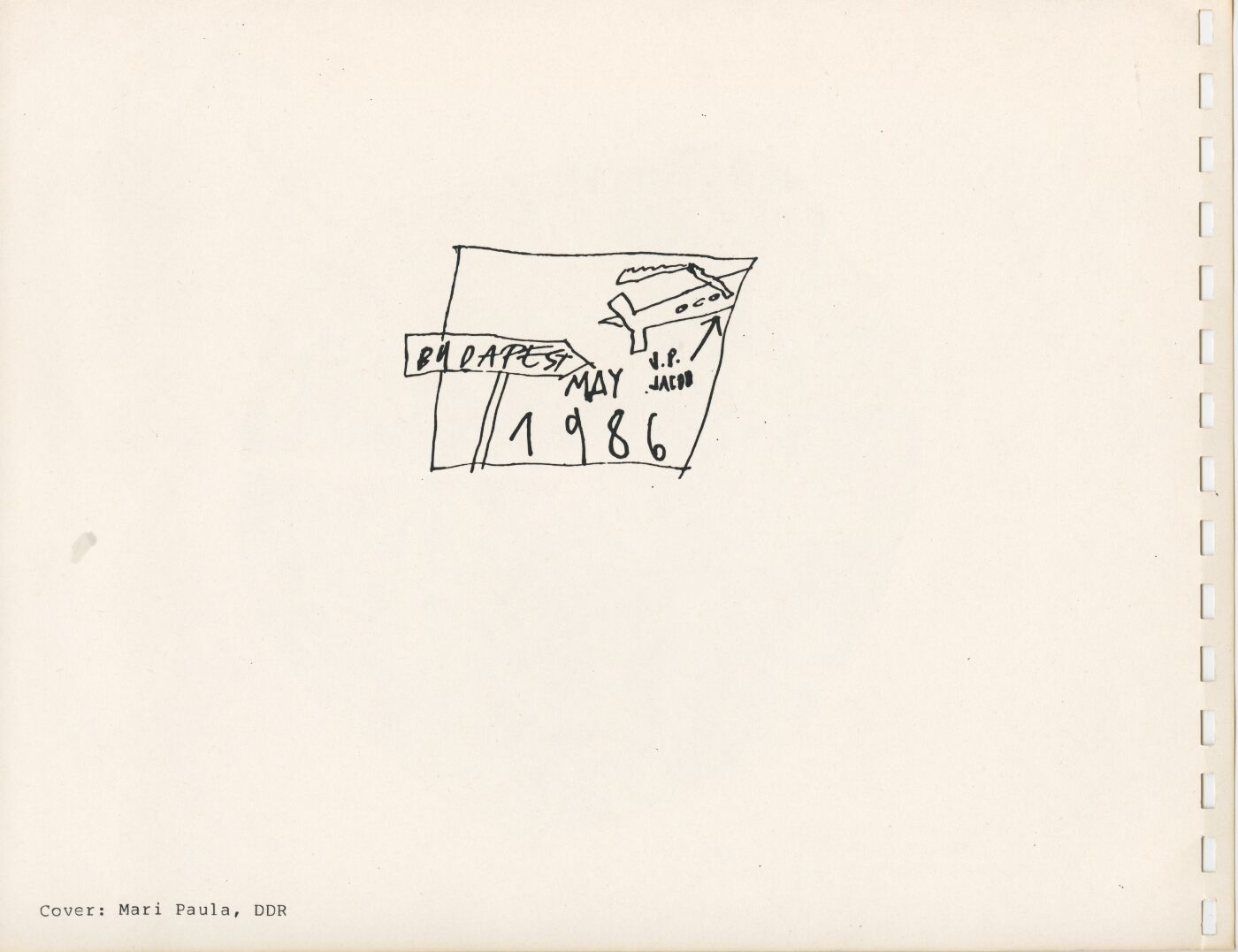

The Second International Portfolio (BP Ed, exhibition catalog, Liget Galeria, Budapest)

Photography from the US, USSR, and Eastern Europe (lecture tour, Liget Galeria, Budapest, Hungary; Praconia Dziekanka, Warsaw, Poland; Attic Gallery, Lodz, Poland; private homes in Czechoslovakia and the GDR)

1987

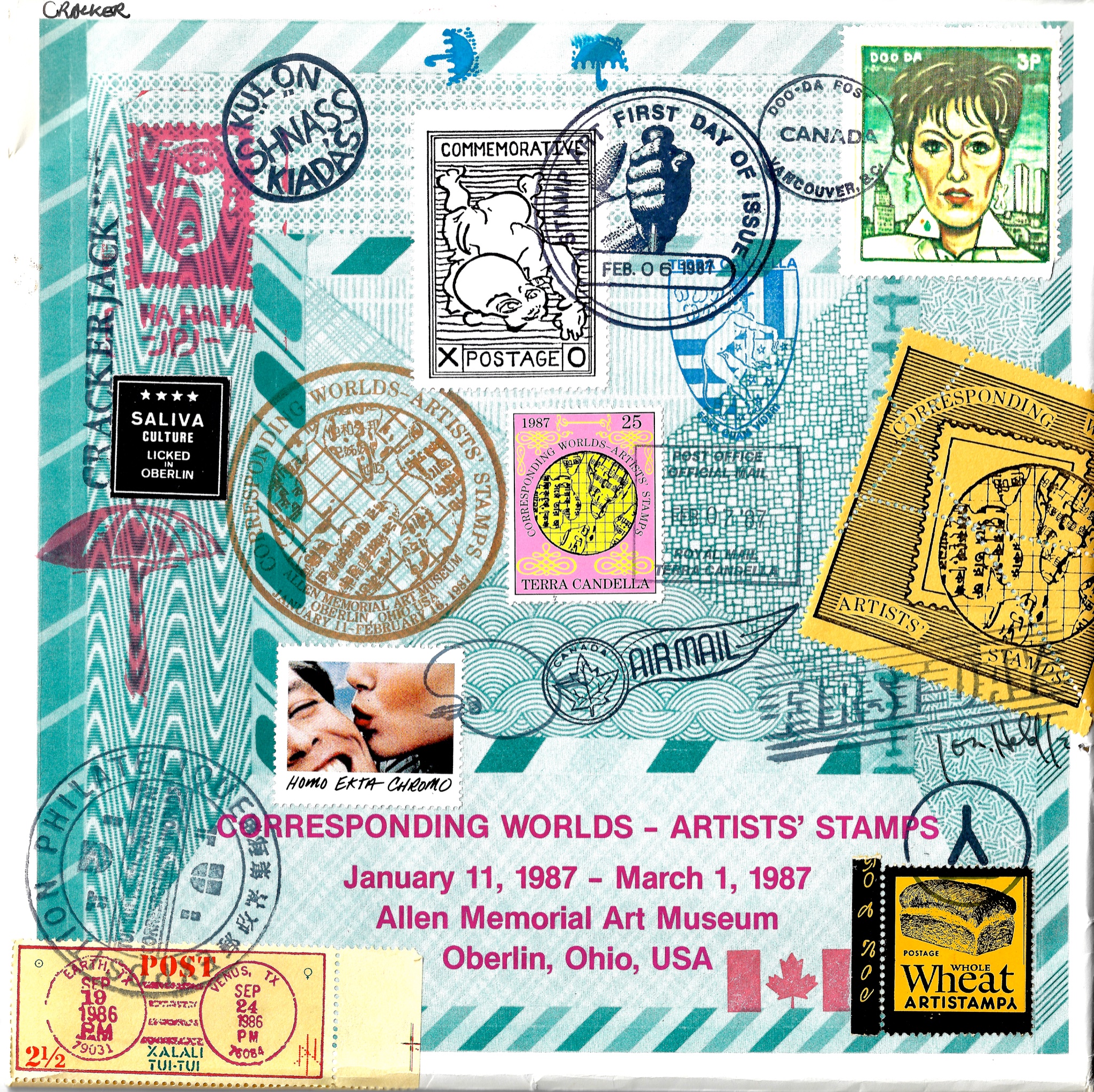

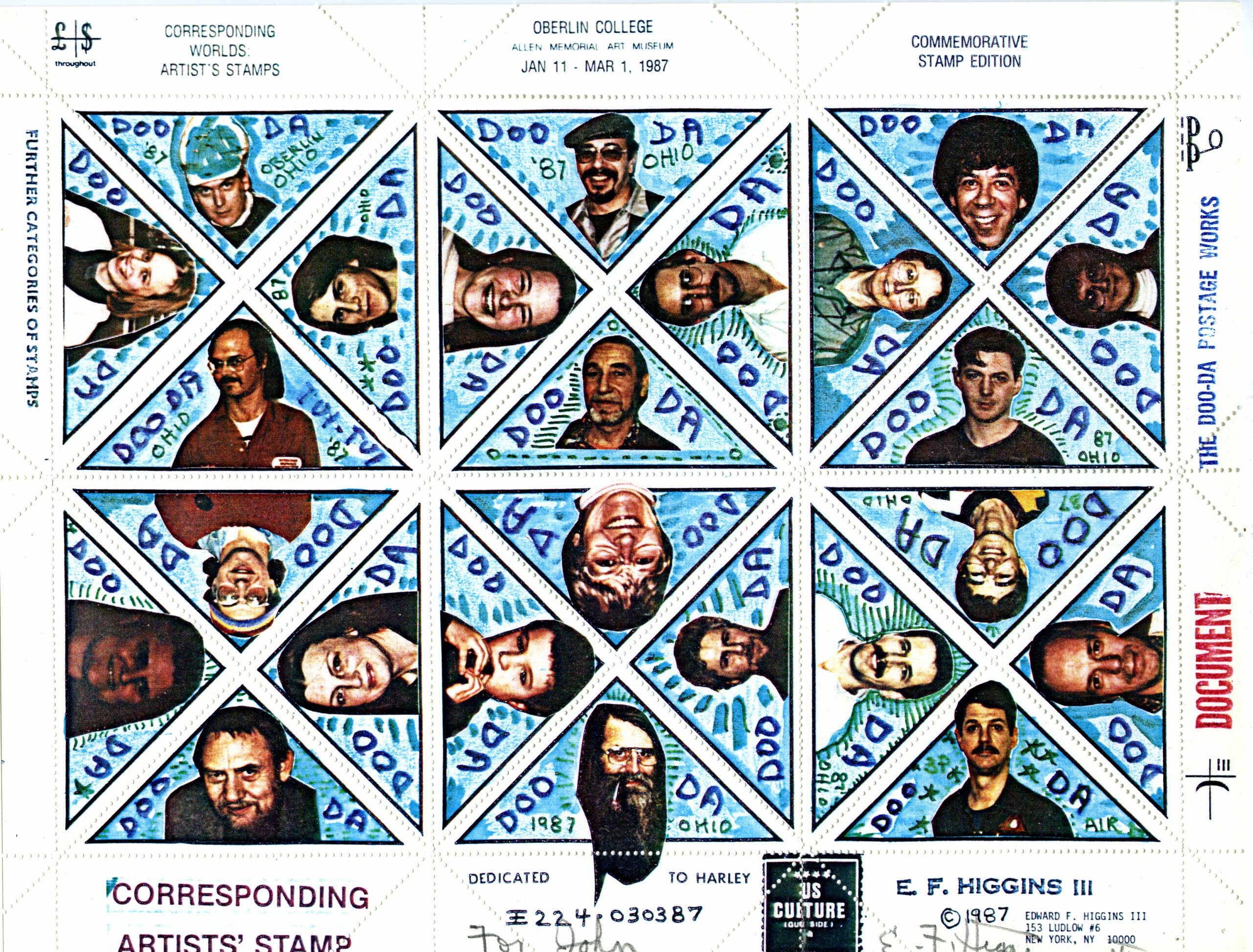

“Editorial” (catalog essay for Corresponding Worlds/Artists’ Stamps, Harley Francis, ed., Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, OH)

Artists in a Repressive Society (lecture, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, OH)

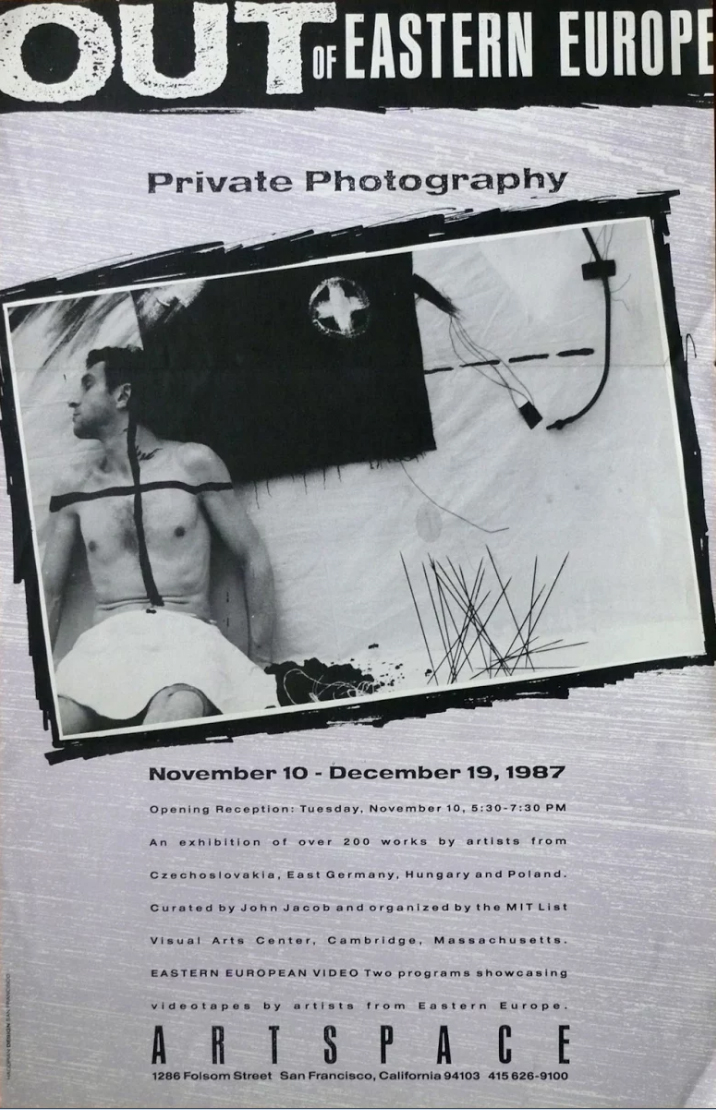

Out of Eastern Europe: Private Photography (exhibition + catalog, List Visual Arts Center at MIT, Cambridge, MA)

Private Photography from Eastern Europe (exhibition, Rosa Esman Gallery, NYC)

The Photo Diary of Anna Beata Bohdziewicz (exhibition, Photographic Resource Center, Boston, MA; Red Eye Gallery, RISD, Providence, RI)

Private Photography from Eastern Europe (lecture, Society for Photographic Education Annual Conference, San Diego, CA)

1988

Leupold/Leupold: Staged Photographs (exhibition, Maine College of Art, Portland, ME)

“Photems Or: A History of the World in Five Parts,” (catalog essay for Photems, CEPA Quarterly, Winter/Spring)

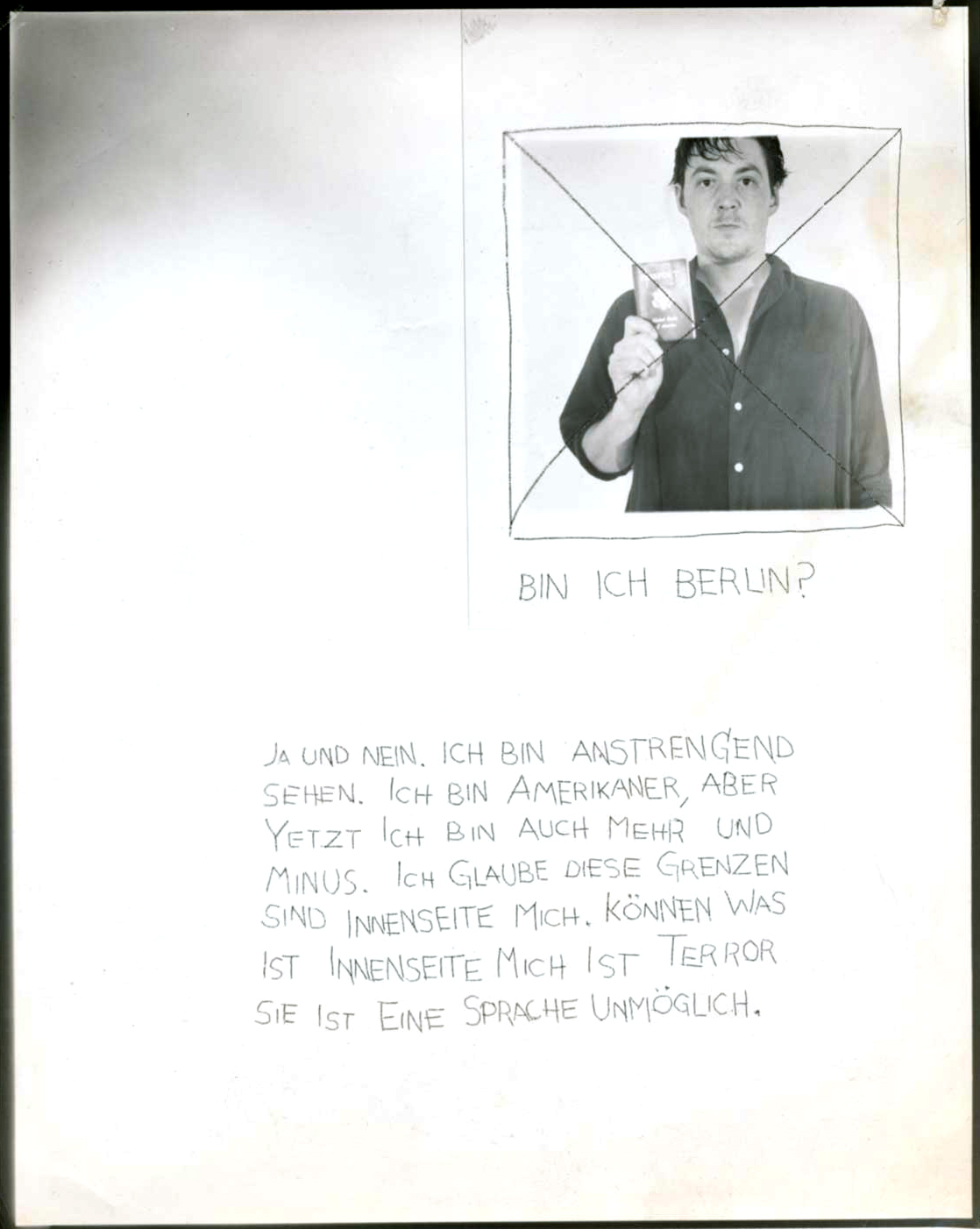

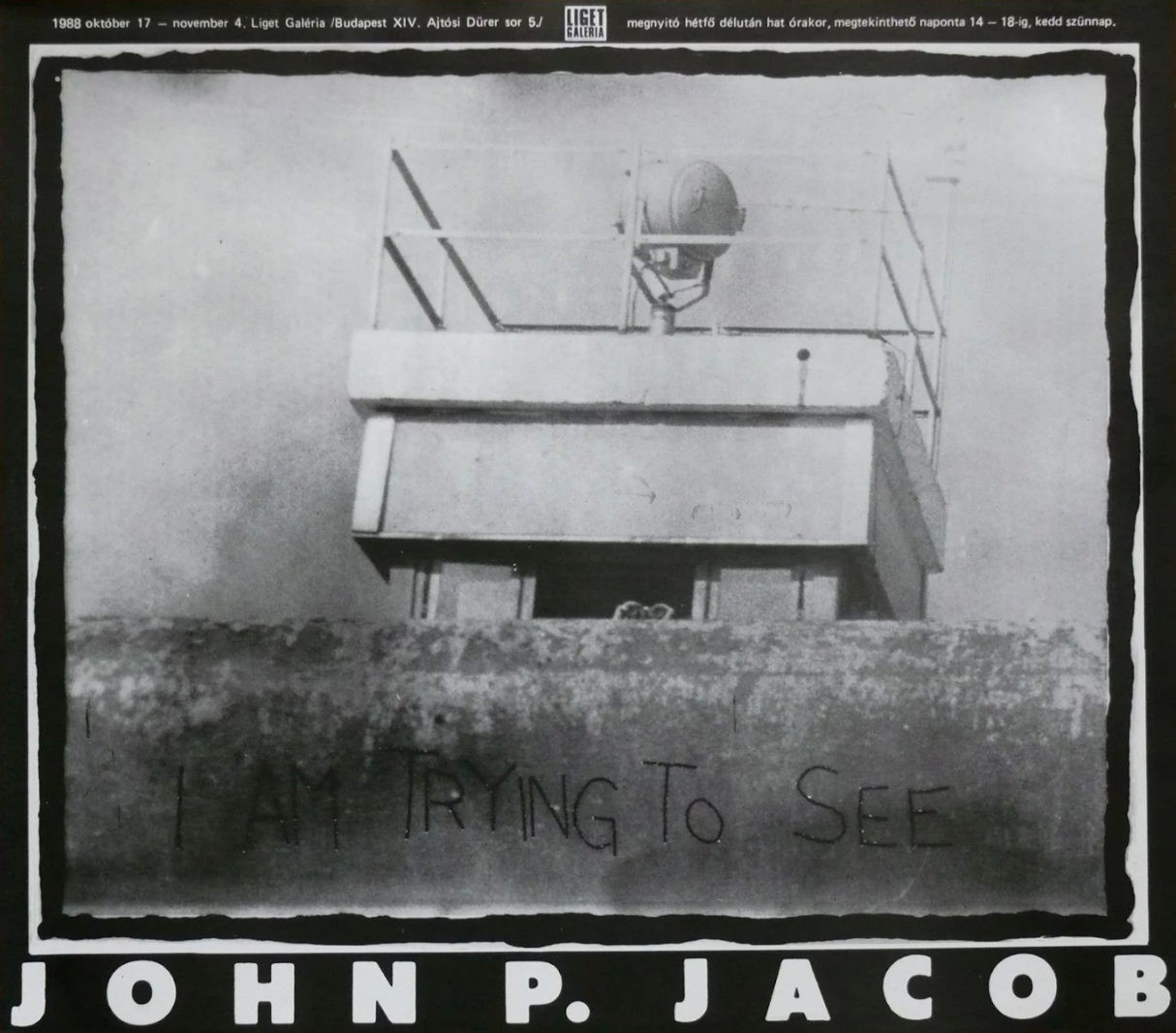

John P. Jacob: I am Trying to See (exhibition + catalog, Liget Galeria, Budapest)

“Thomas Florscheutz: Extracting Meaning from Myth” (catalog essay for Thomas Florscheutz, Anderson Gallery, Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA)

1989

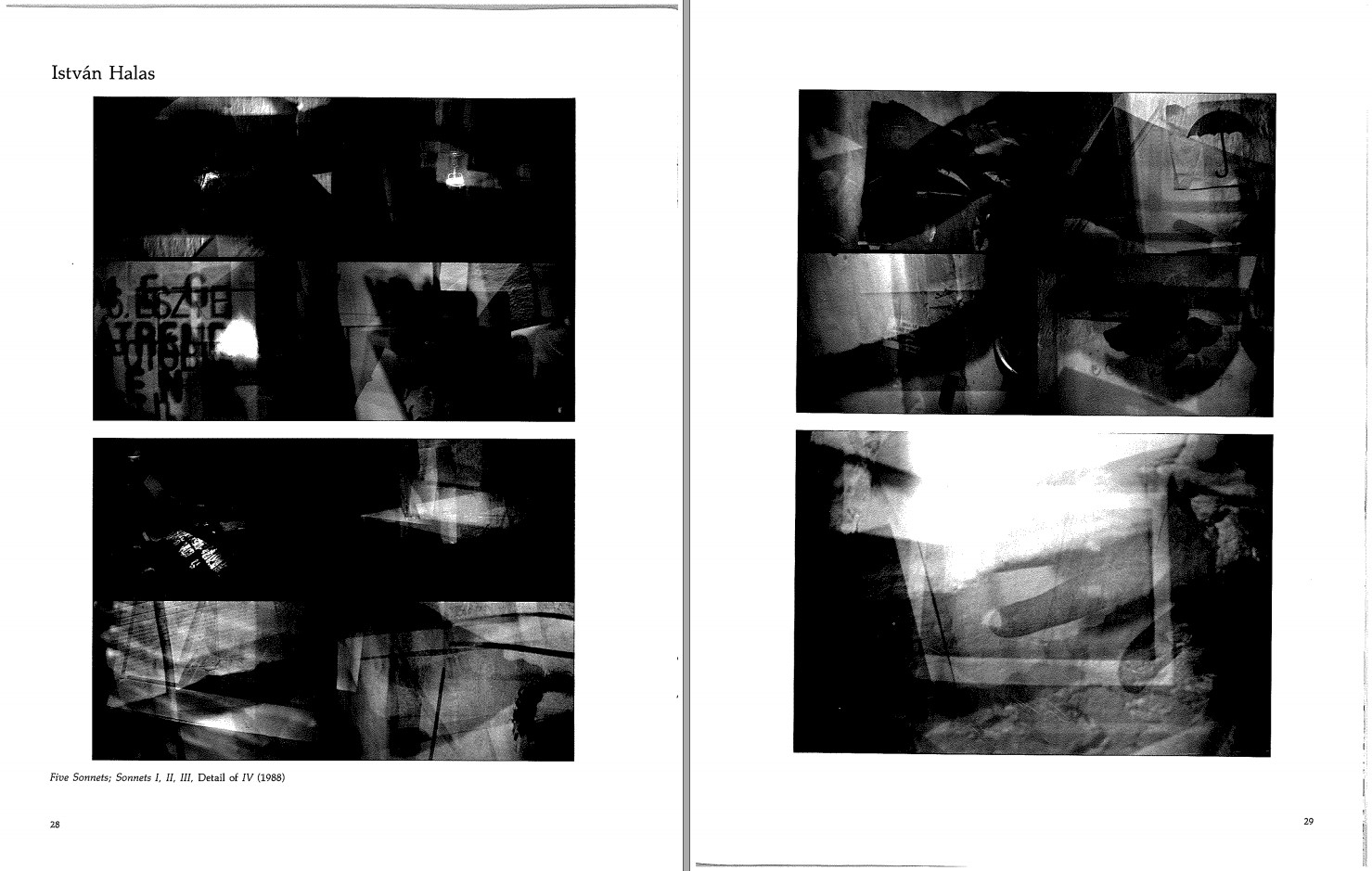

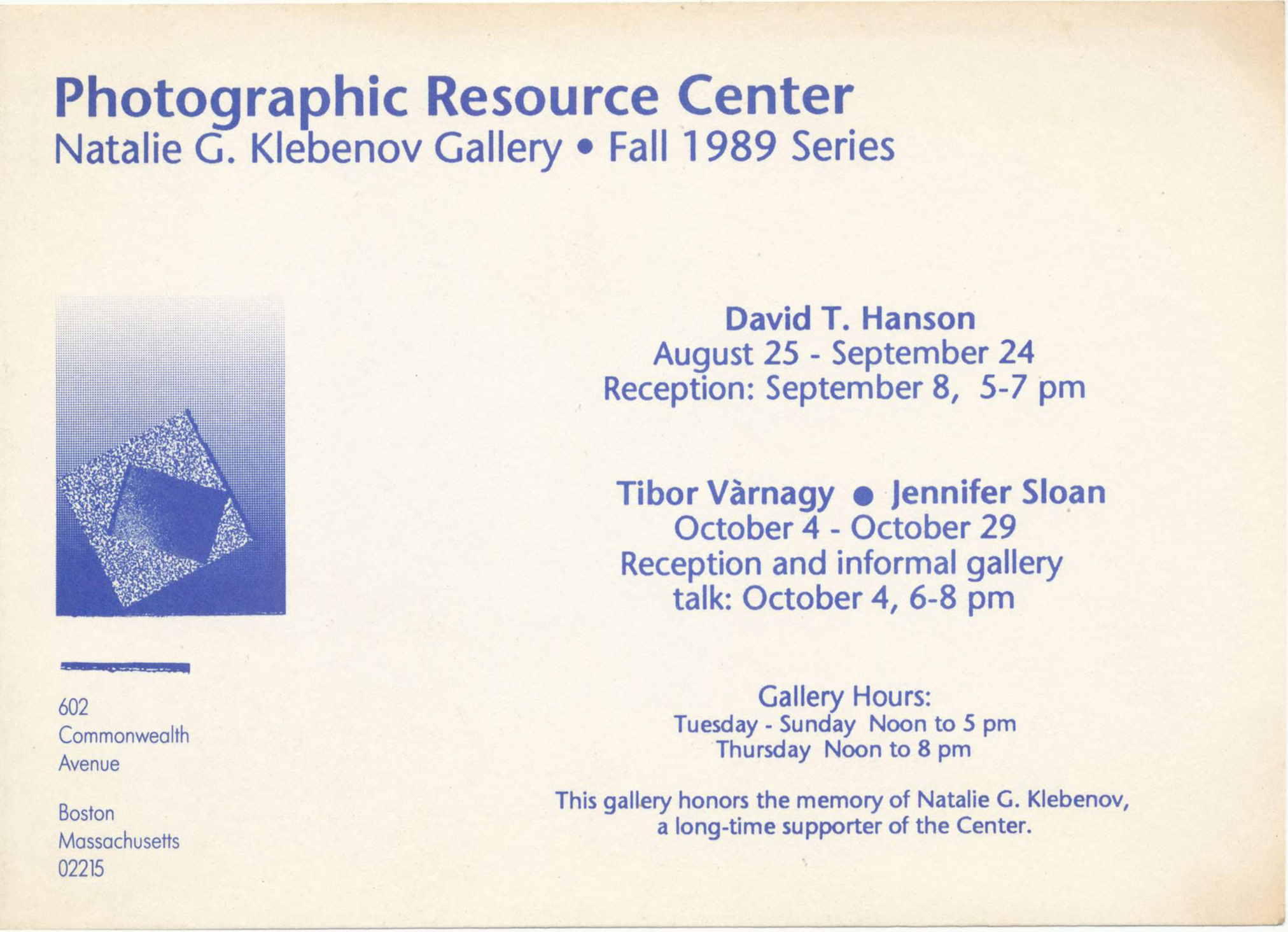

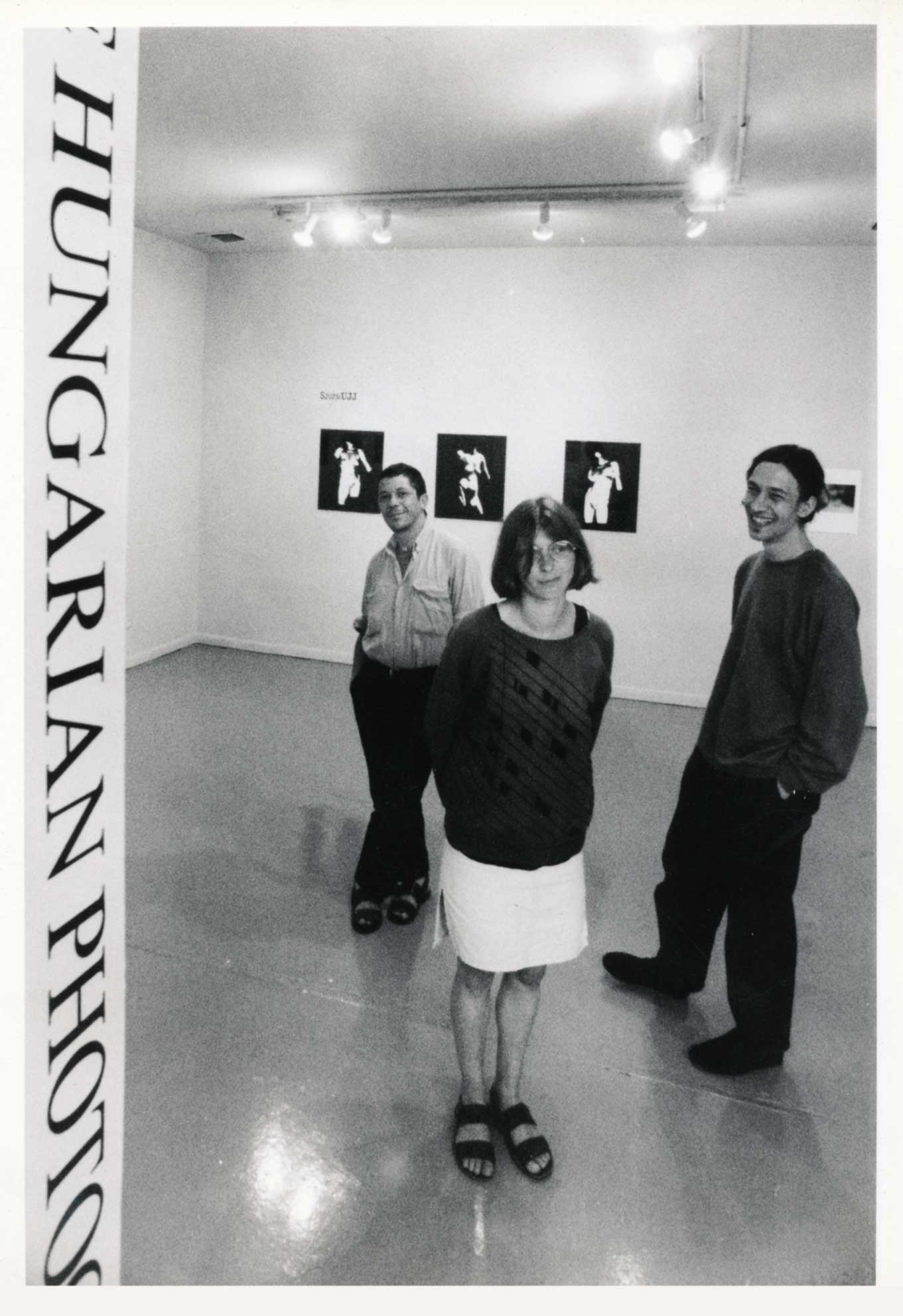

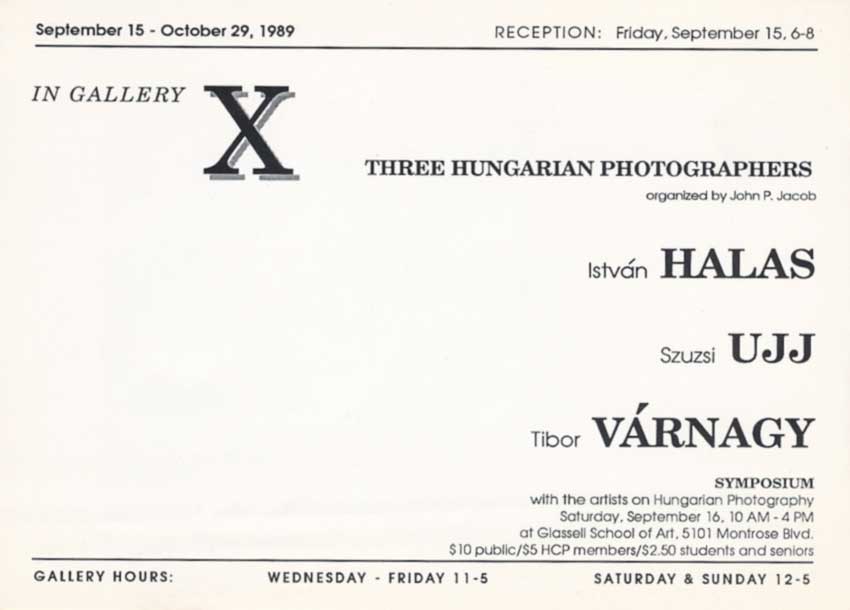

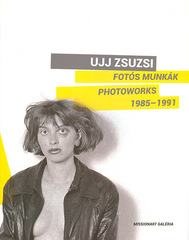

Three Hungarian Photographers: Halas, Ujj, Várnagy (exhibition, Houston Center for Photograpy, TX)

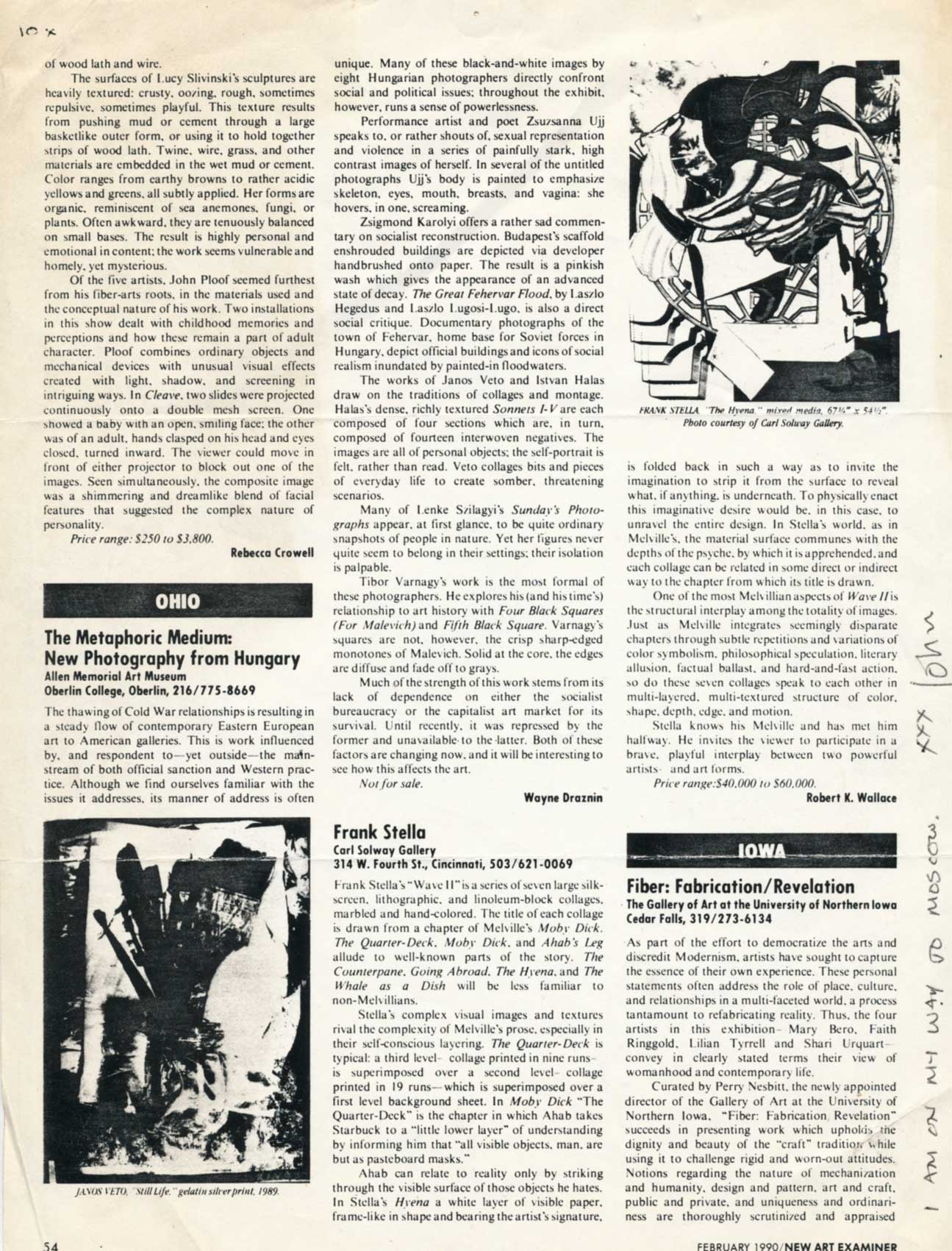

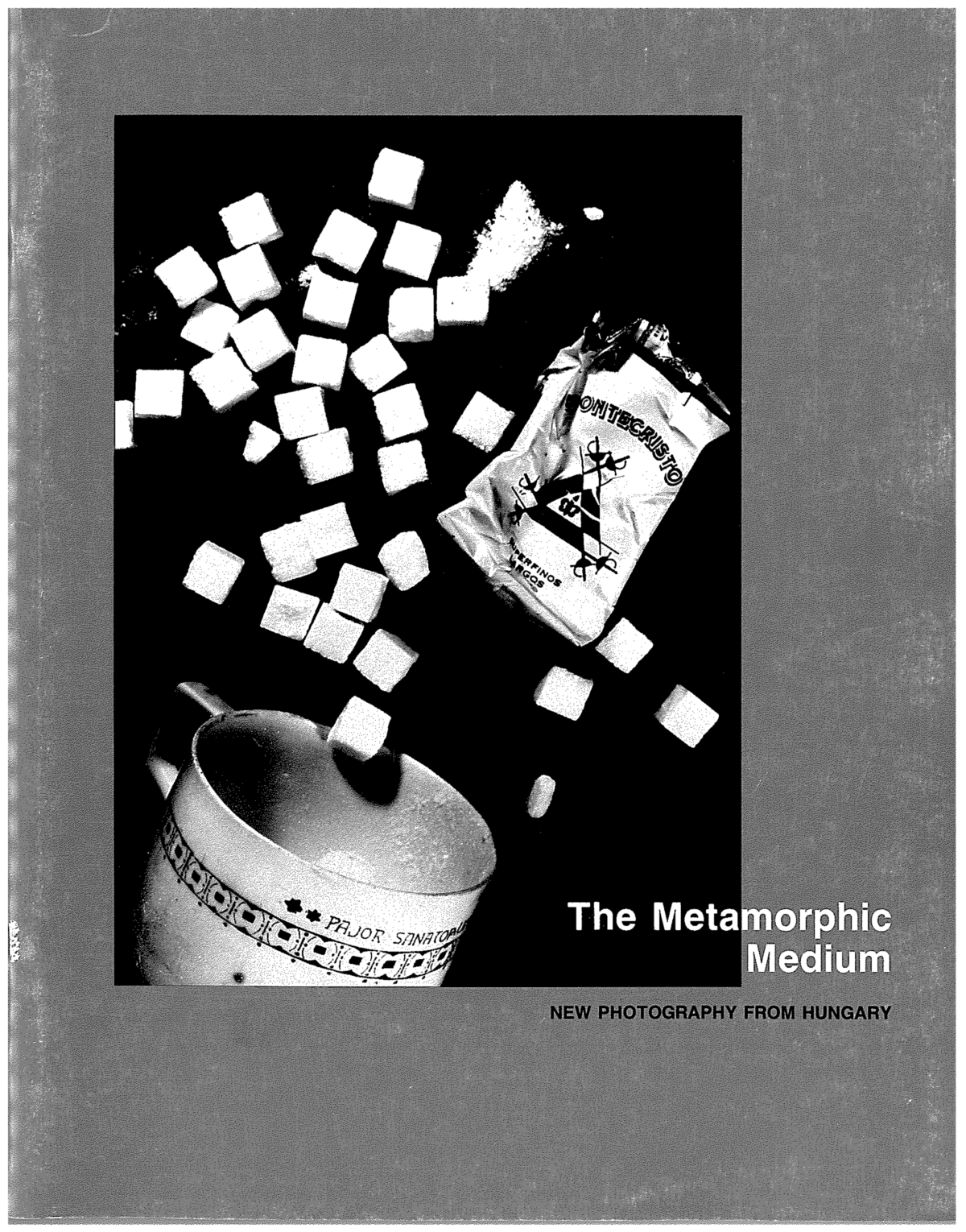

The Metamorphic Medium: New Photography from Hungary (exhibition + catalog, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin)

Tibor Várnagy (exhibition, Photographic Resource Center, Boston, MA)

Photography from Hungary and the USSR (lecture tour with Halas, Ujj, and Várnagy, Center for Soviet and East European Studies, University of Texas at Austin; University of Massachusetts, Boston; Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin, OH)

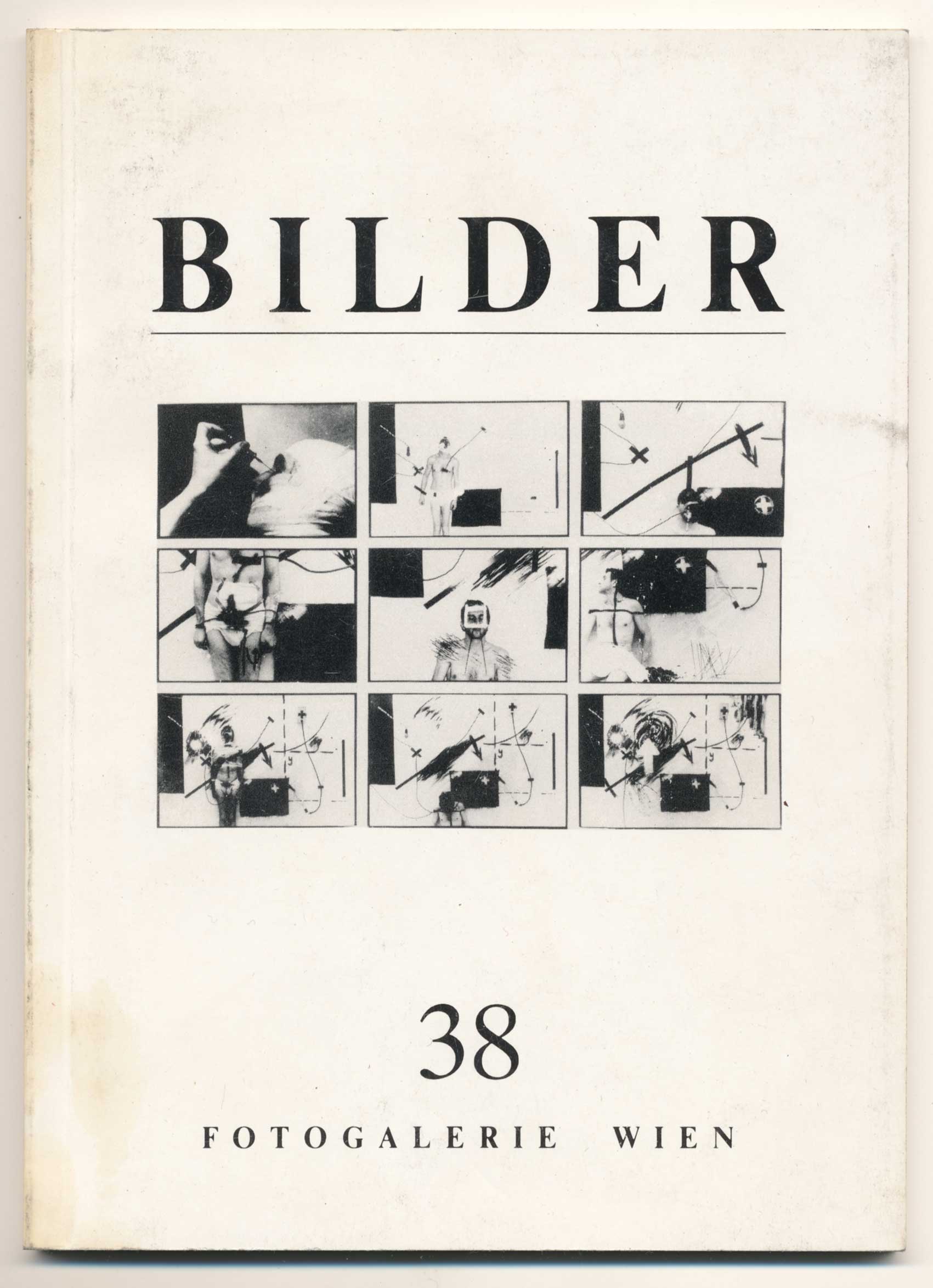

“Hungarian Photography: Ohne Title” (catalog essay for Zeitgenossische Ungarische Fotografie, Fotogalerie Wien, Vienna, Austria)

European Exchange: First East/West Photography Conference (panelist, Tibor Várnagy moderator, Exchange Gallery, Wroclaw, Poland)

“Metamorphic Game: The Art of Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin” (catalog essay for Still Performances, List Visual Arts Center at MIT, Cambridge, MA)

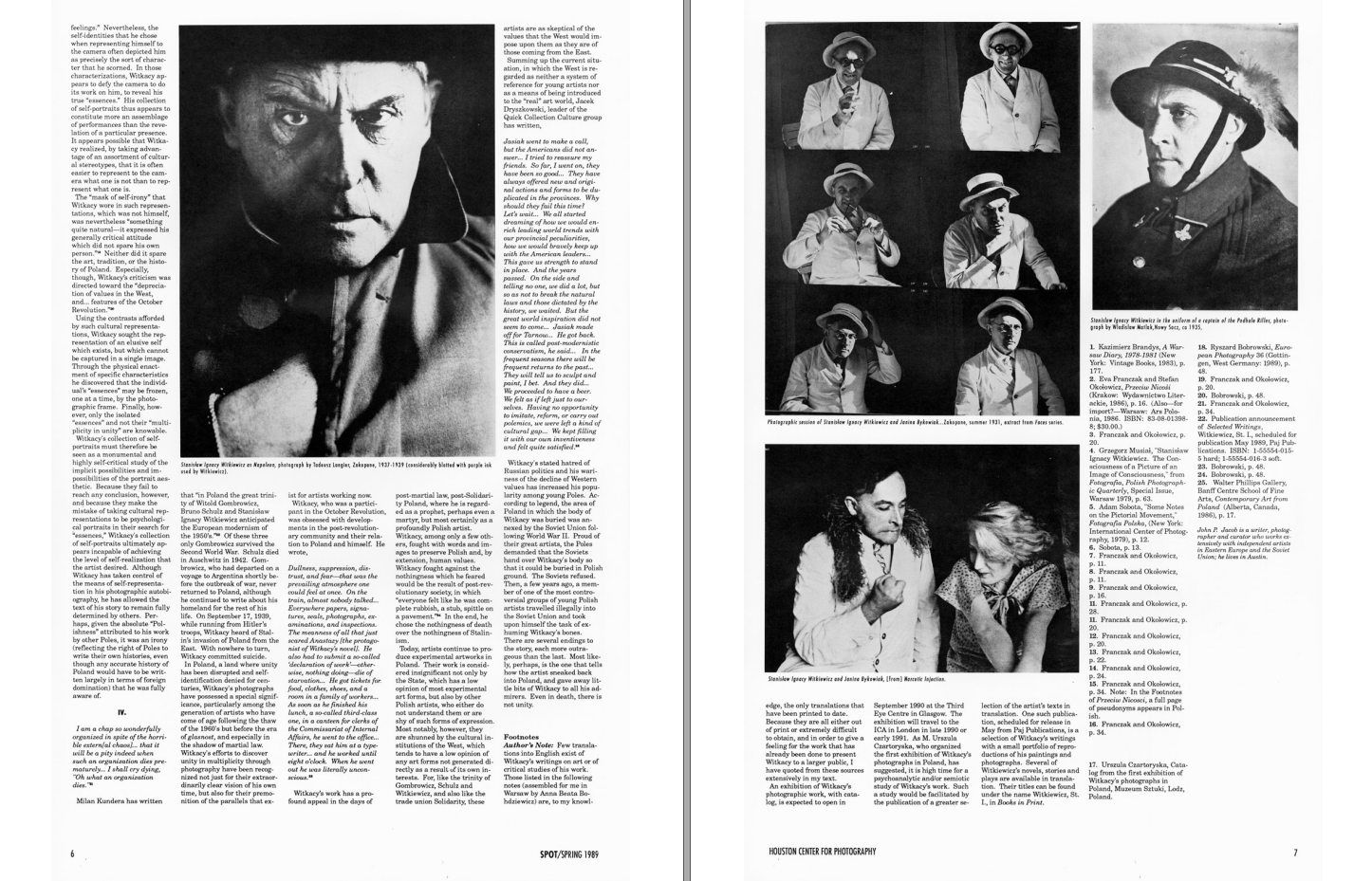

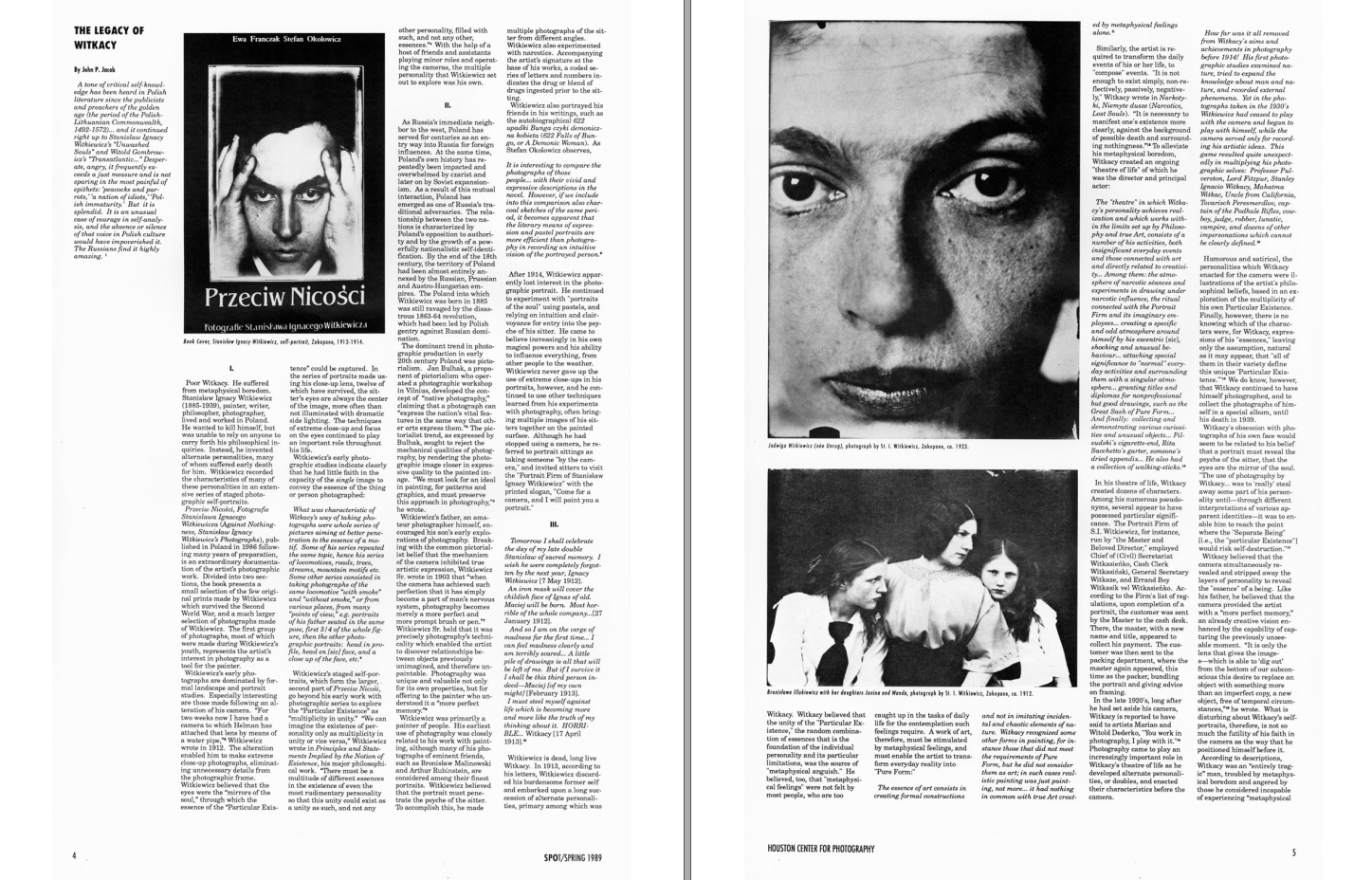

“The Legacy of Witkacy” (essay, Spot, Houston Center for Photography, TX, Spring)

The Second Portfolio (Budapest version)

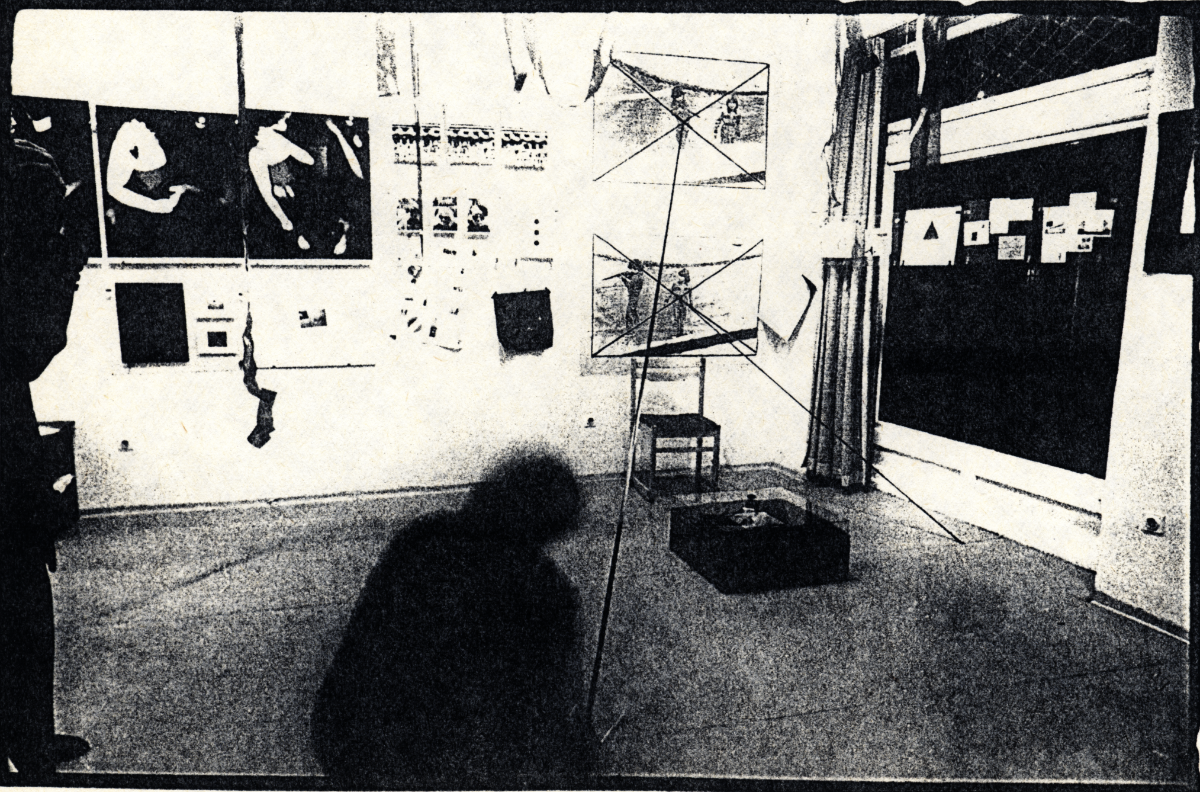

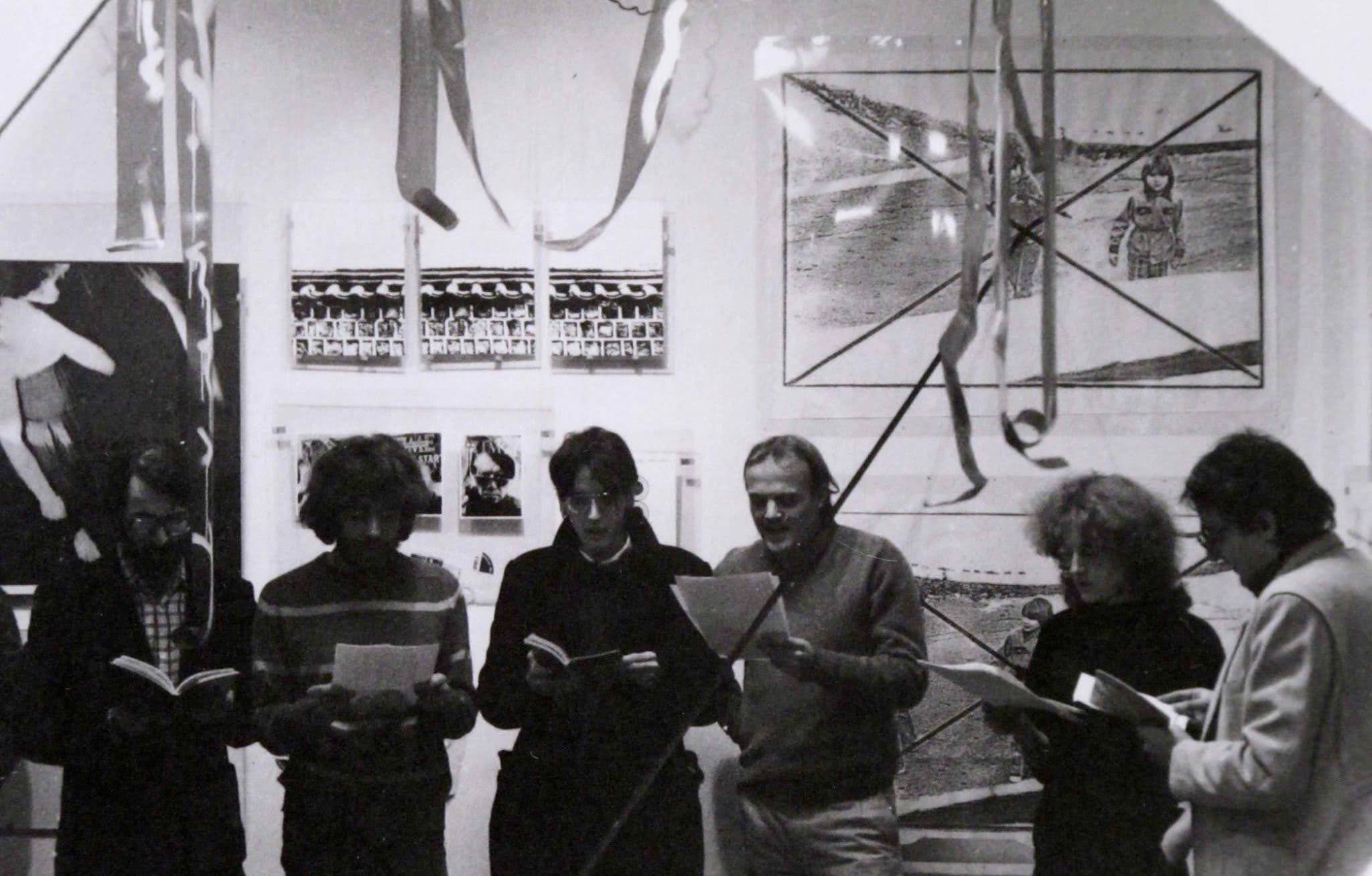

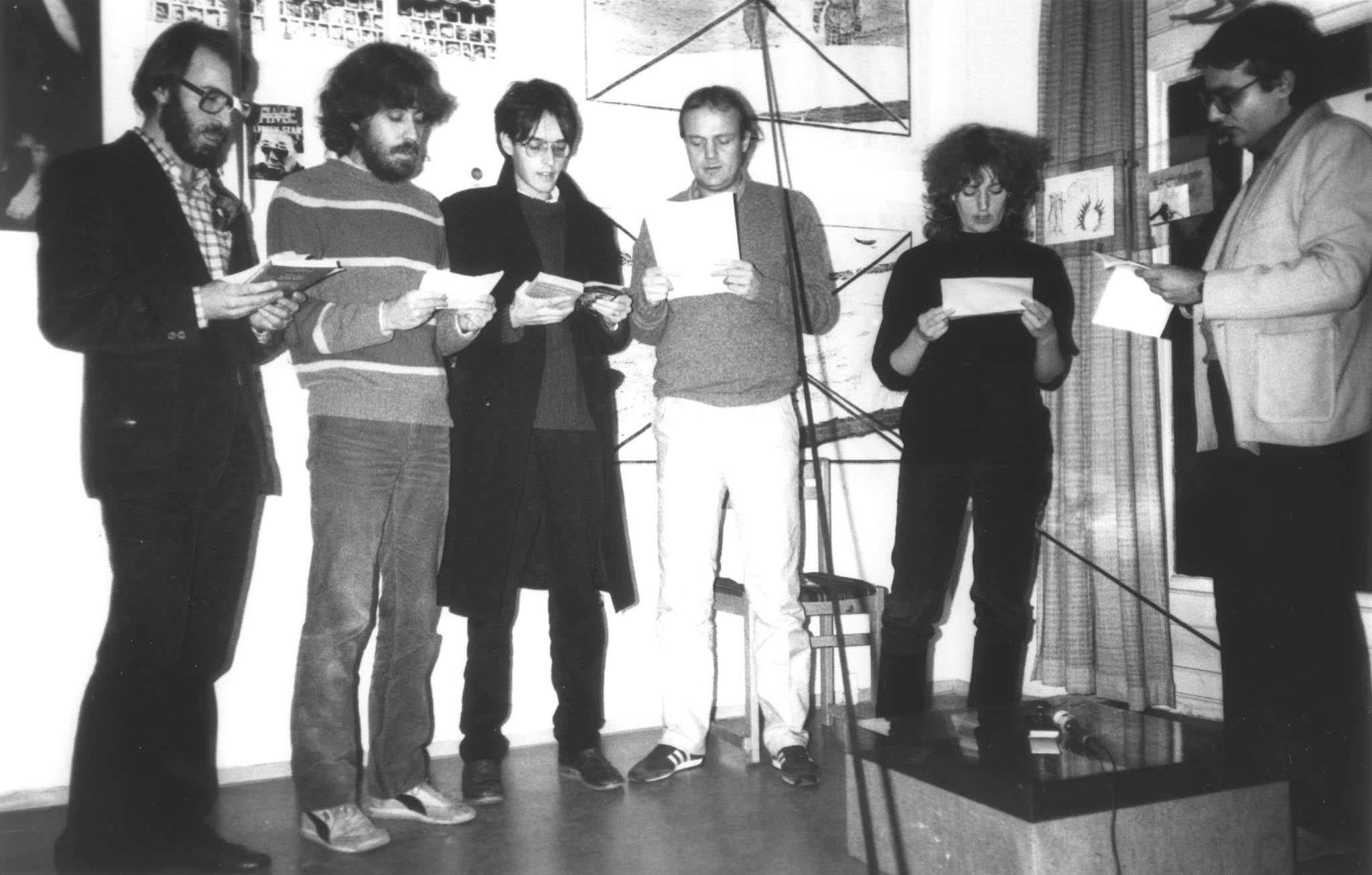

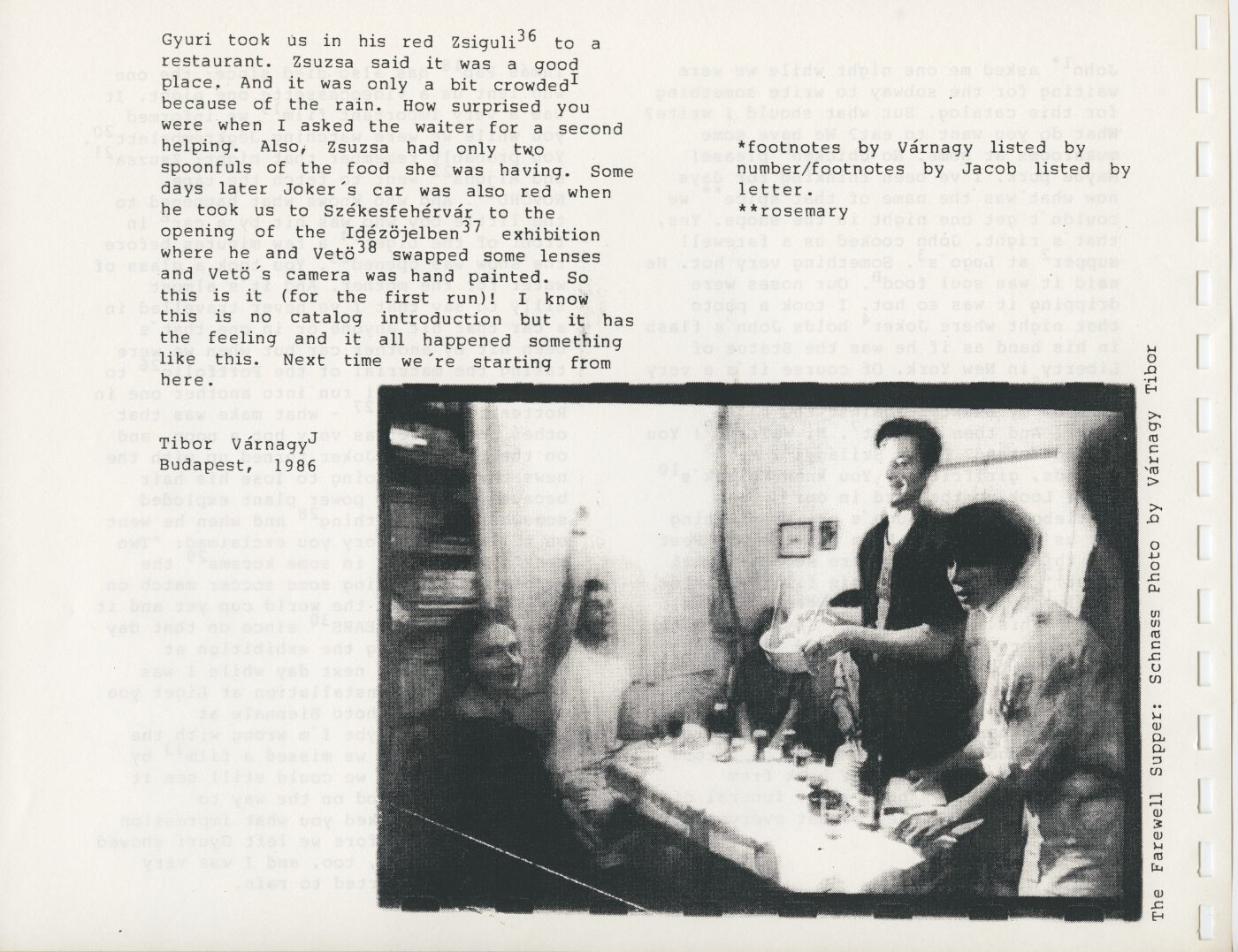

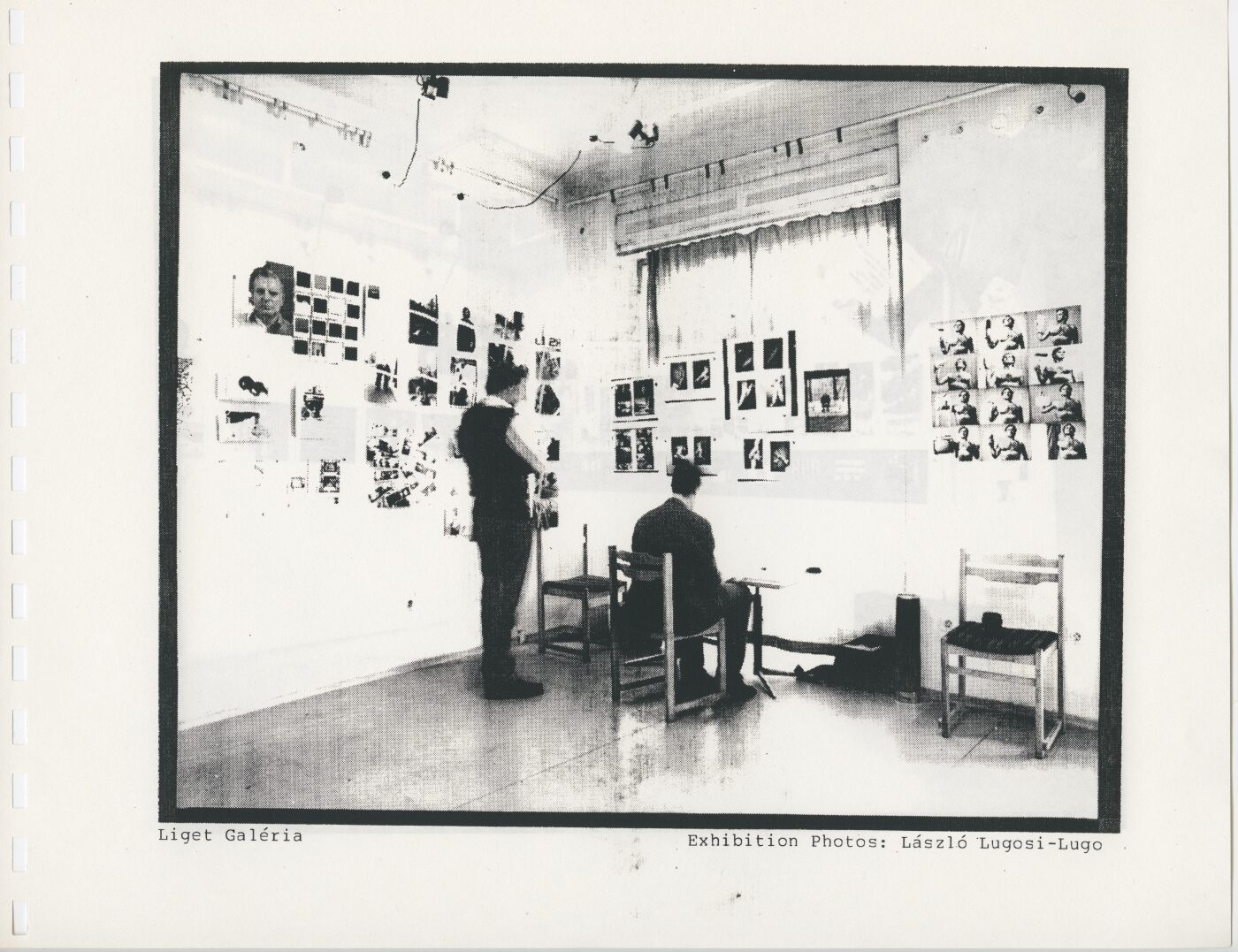

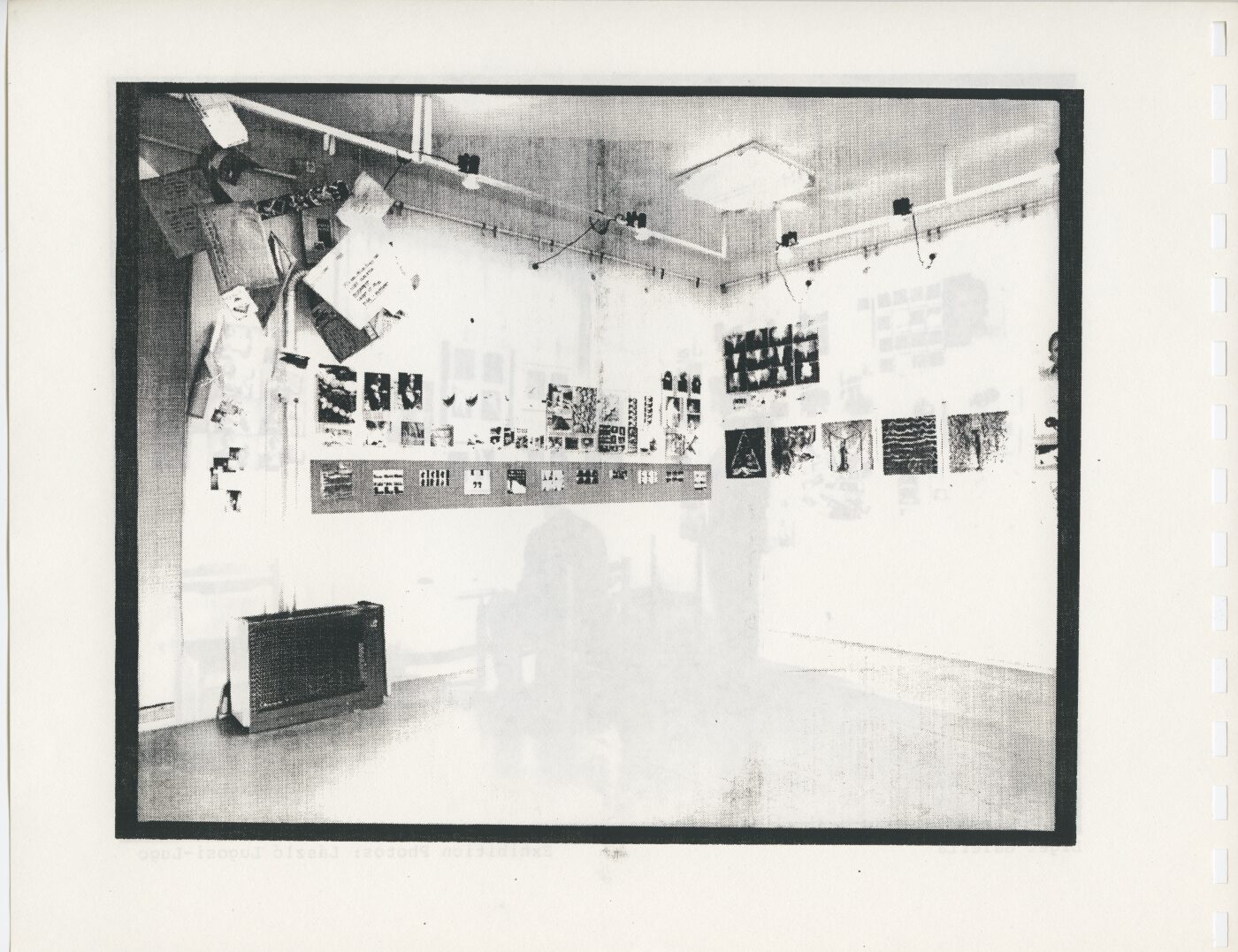

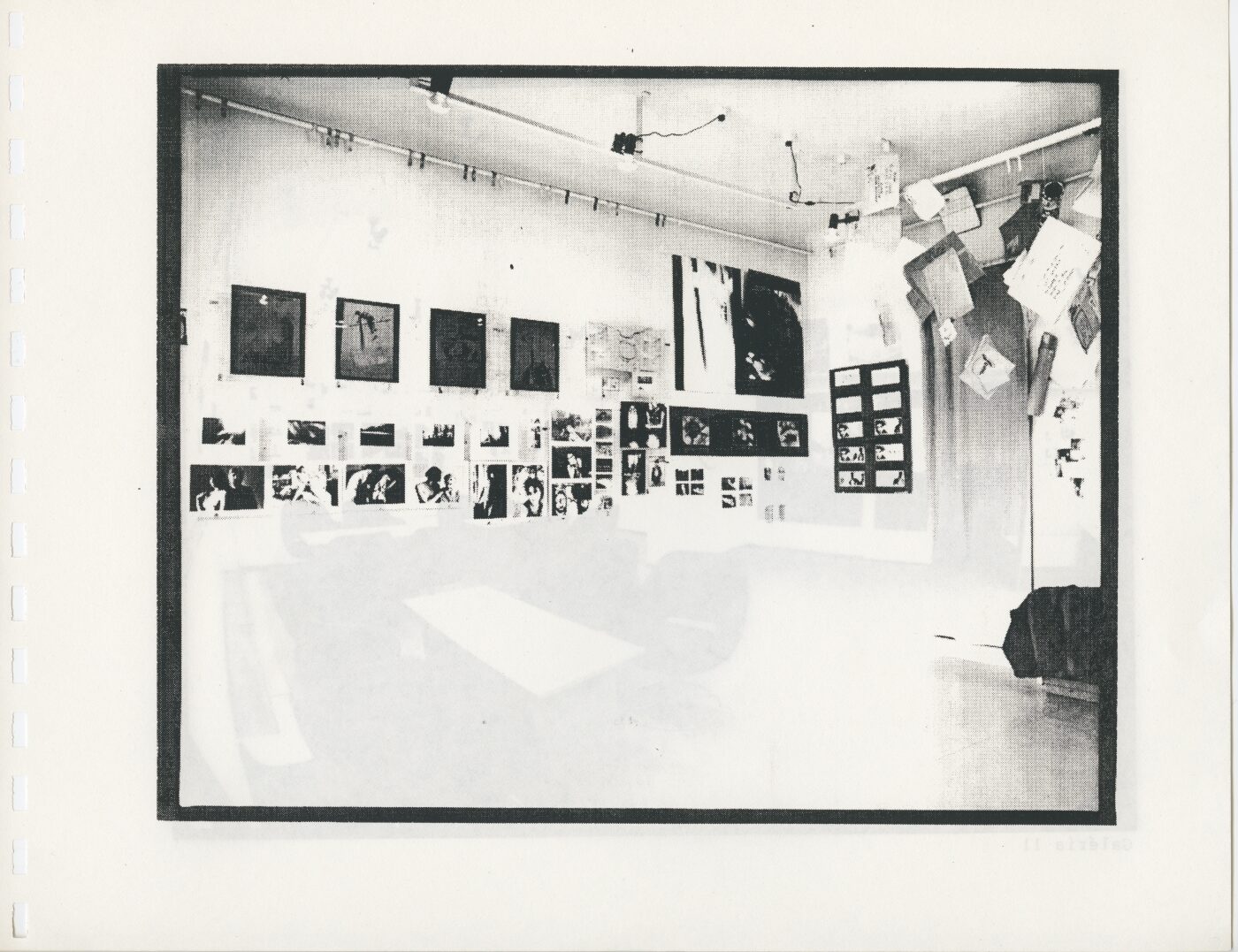

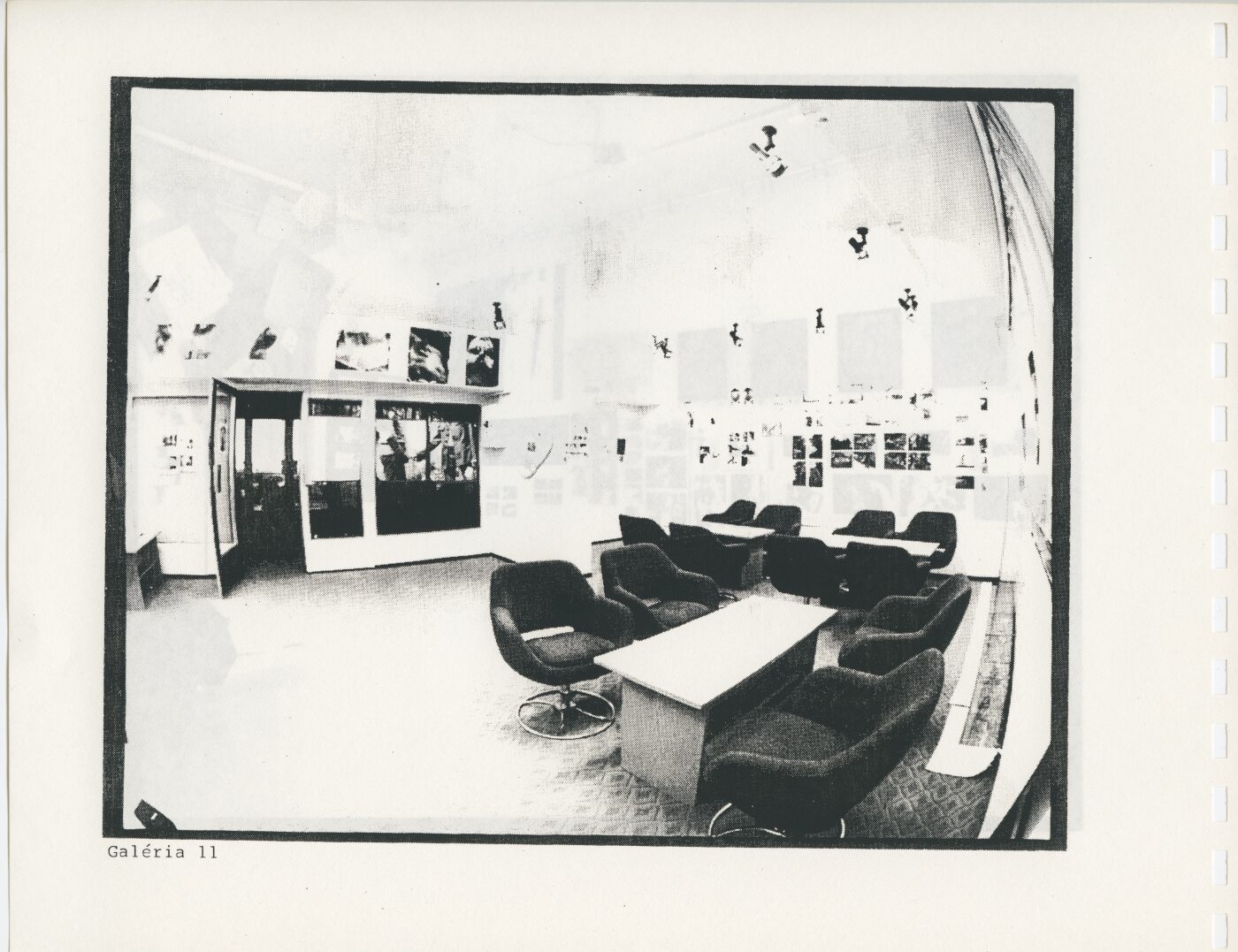

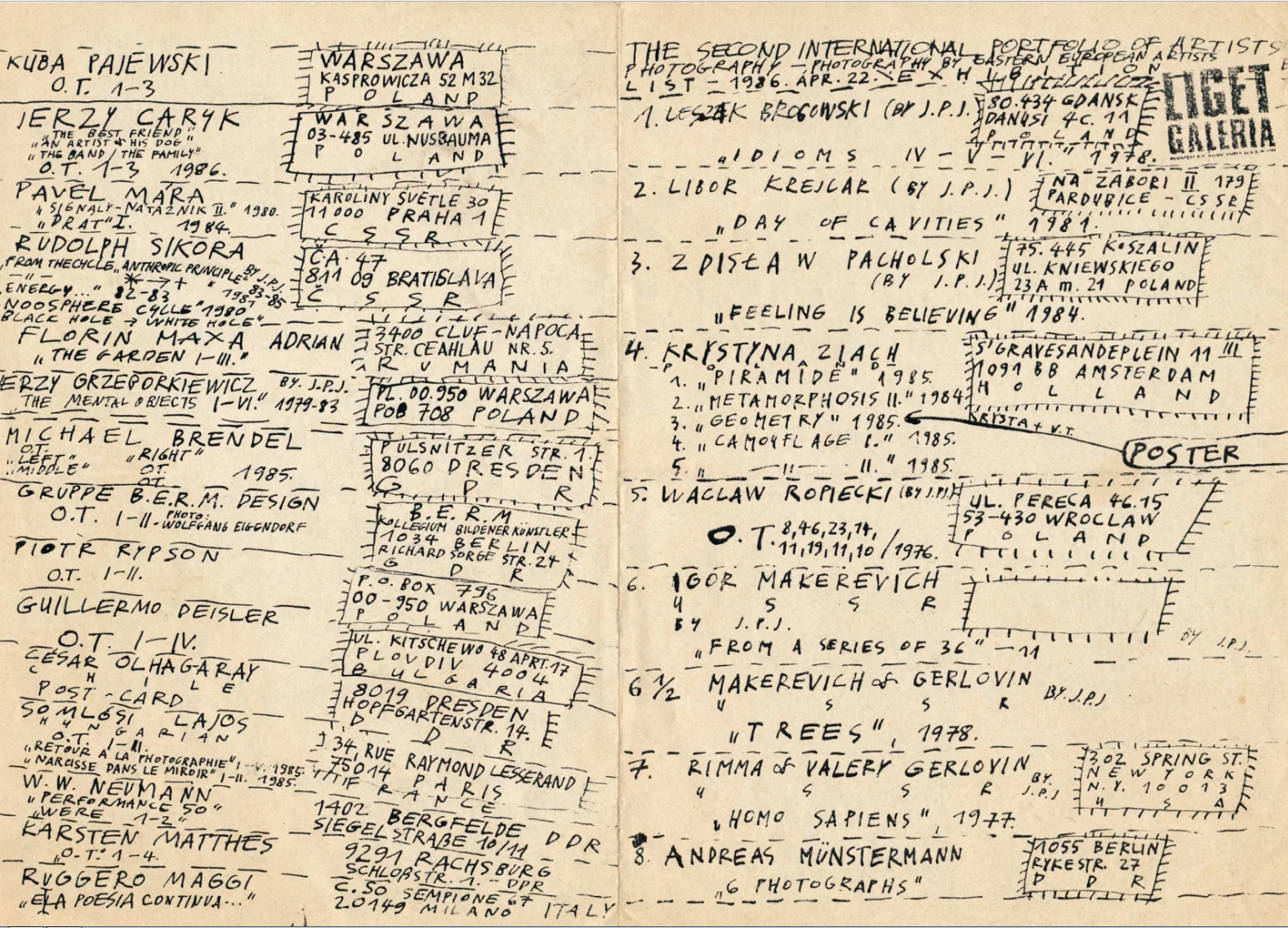

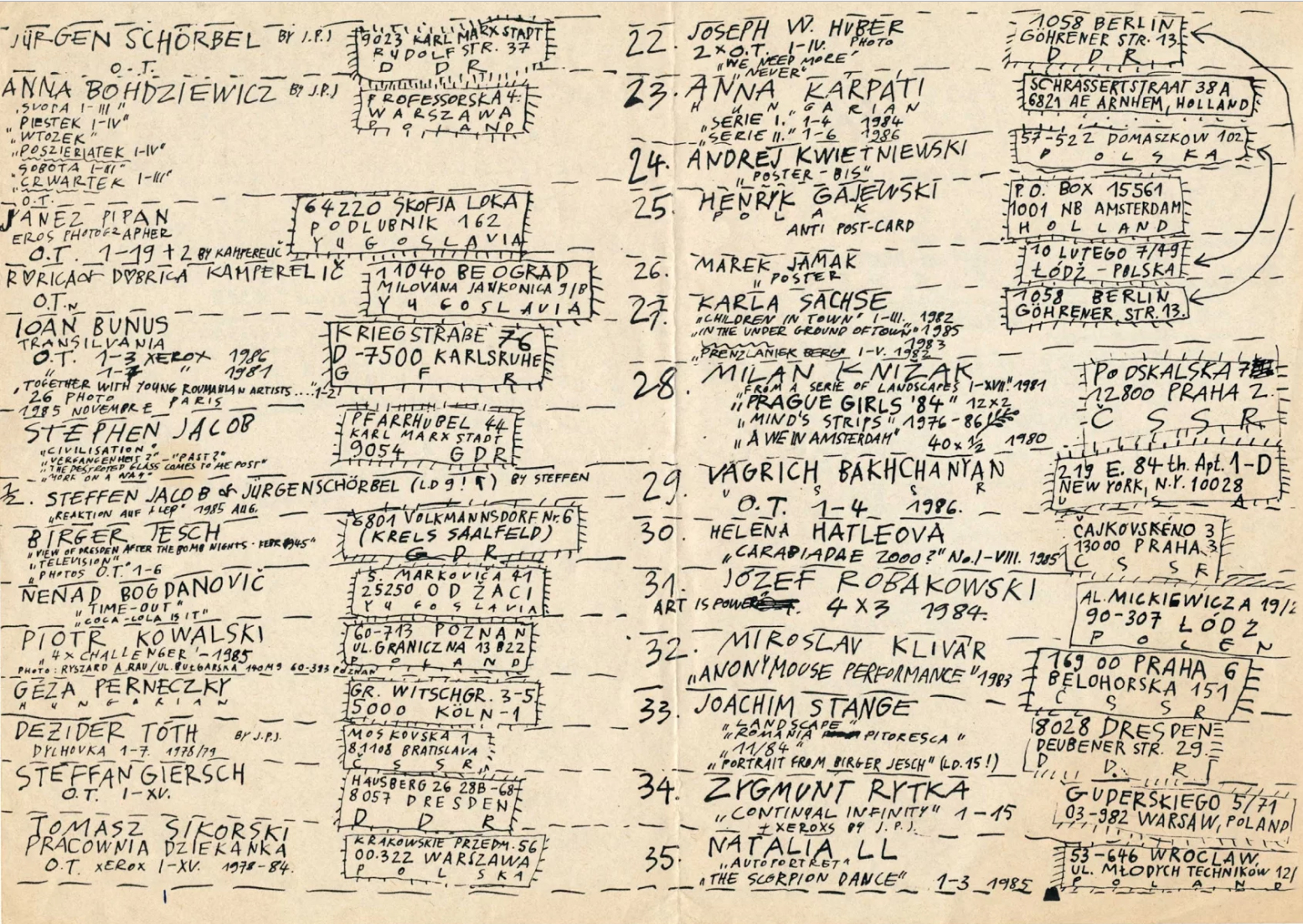

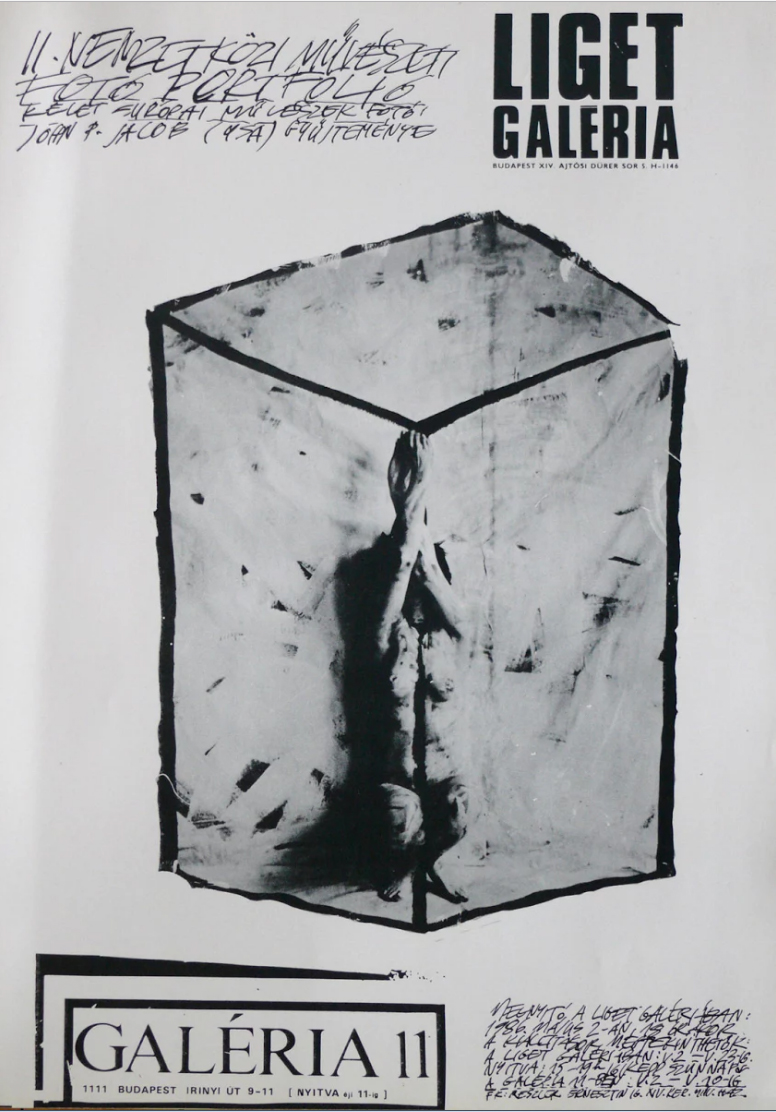

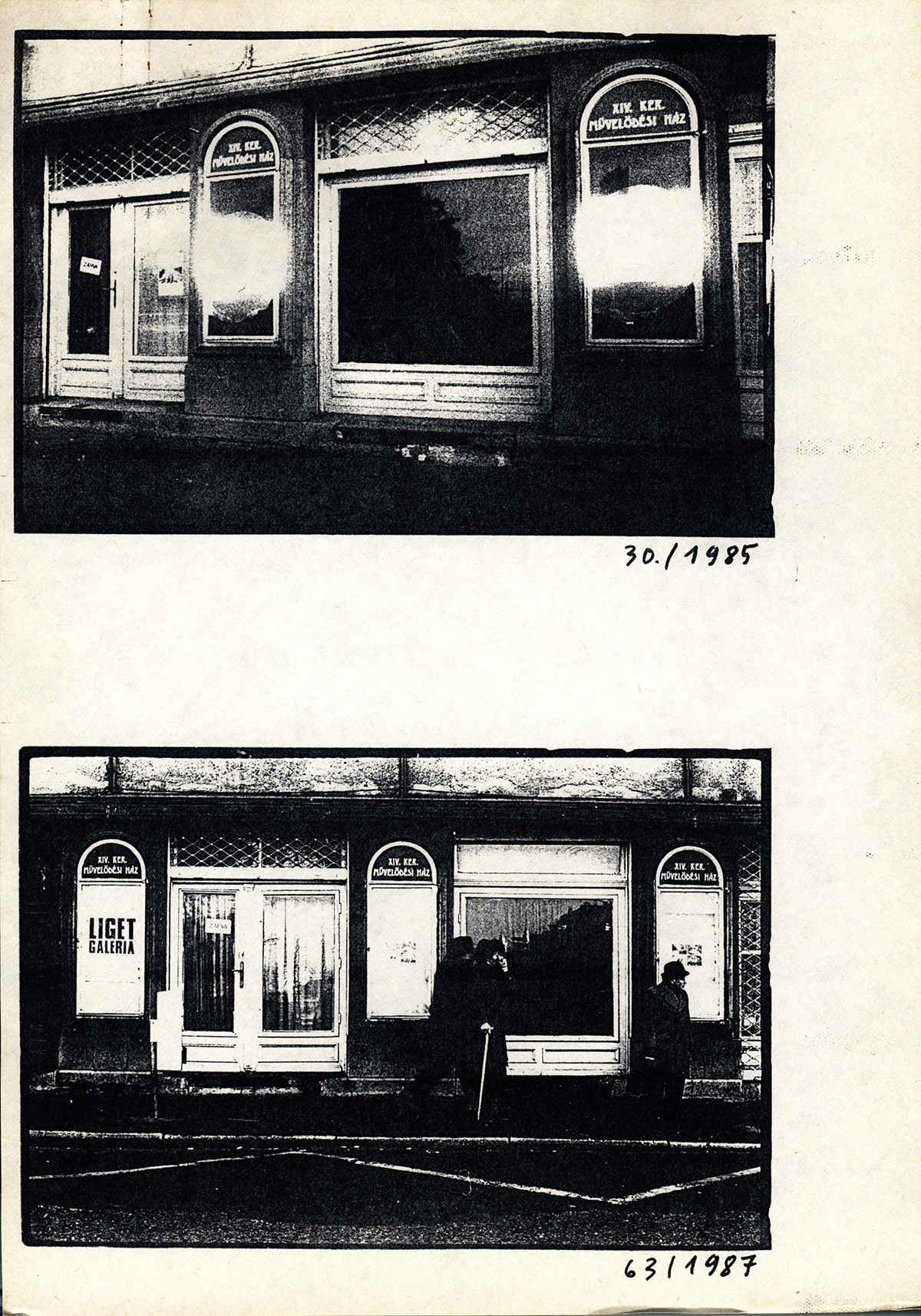

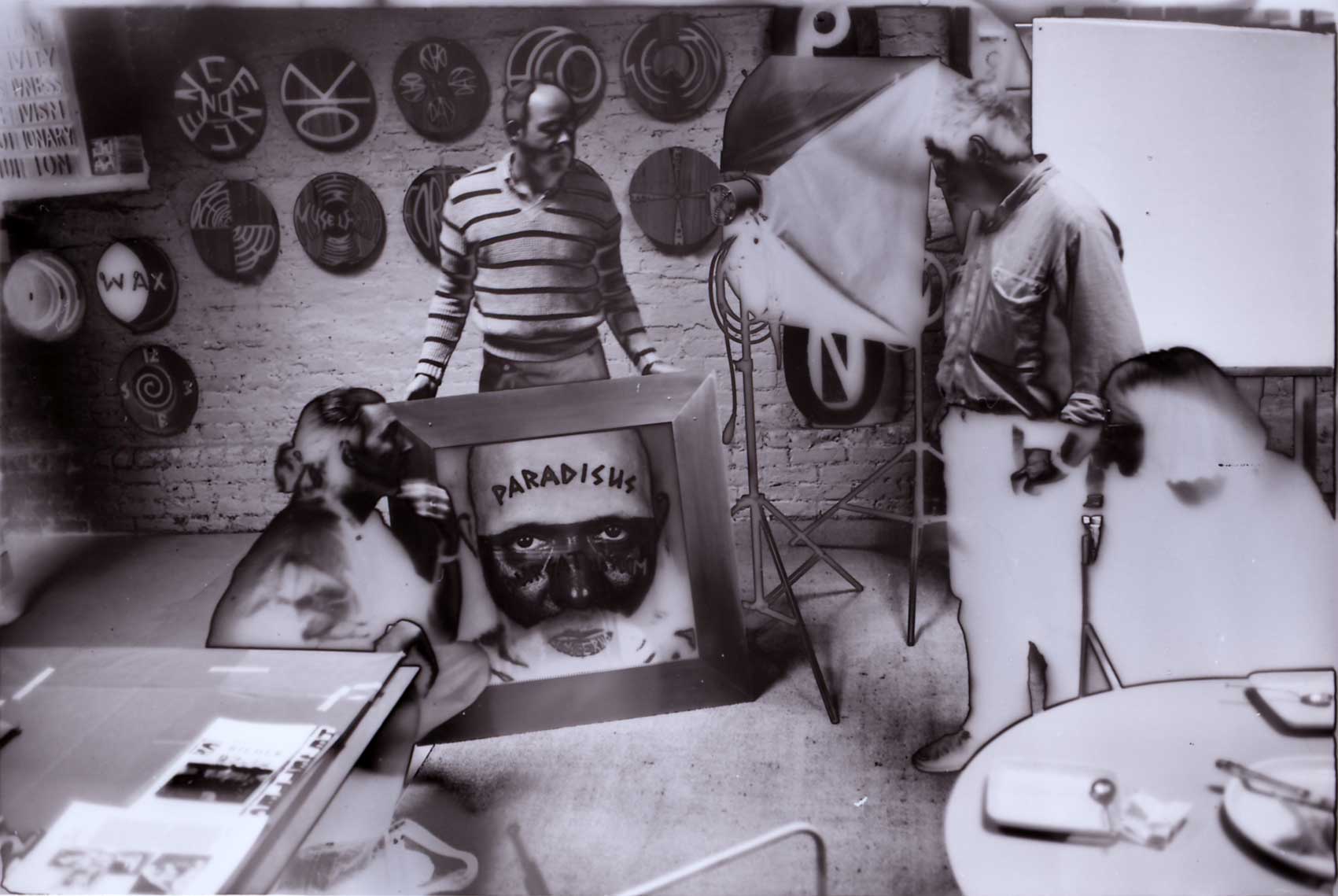

Following Jacob’s participation in the International Day Art mail art exhibition at the Liget Galeria, Budapest, organized by Tamás Soós, director Tibor Várnagy proposed an exhibition of the Second Portfolio in Budapest. Várnagy noted that it would be difficult, and possibly illegal, for such an exhibition to be locally organized. It had not been attempted before. It was a limit, and he wanted to test it. Várnagy invited Jacob to transport and present the Second Portfolio as his personal collection. Várnagy also solicited contributions to be sent directly to the gallery in Budapest. The exhibition opened in May, 1986. Due to the volume of the material submitted, a second exhibition venue, the Galeria 11, was required to present it all.

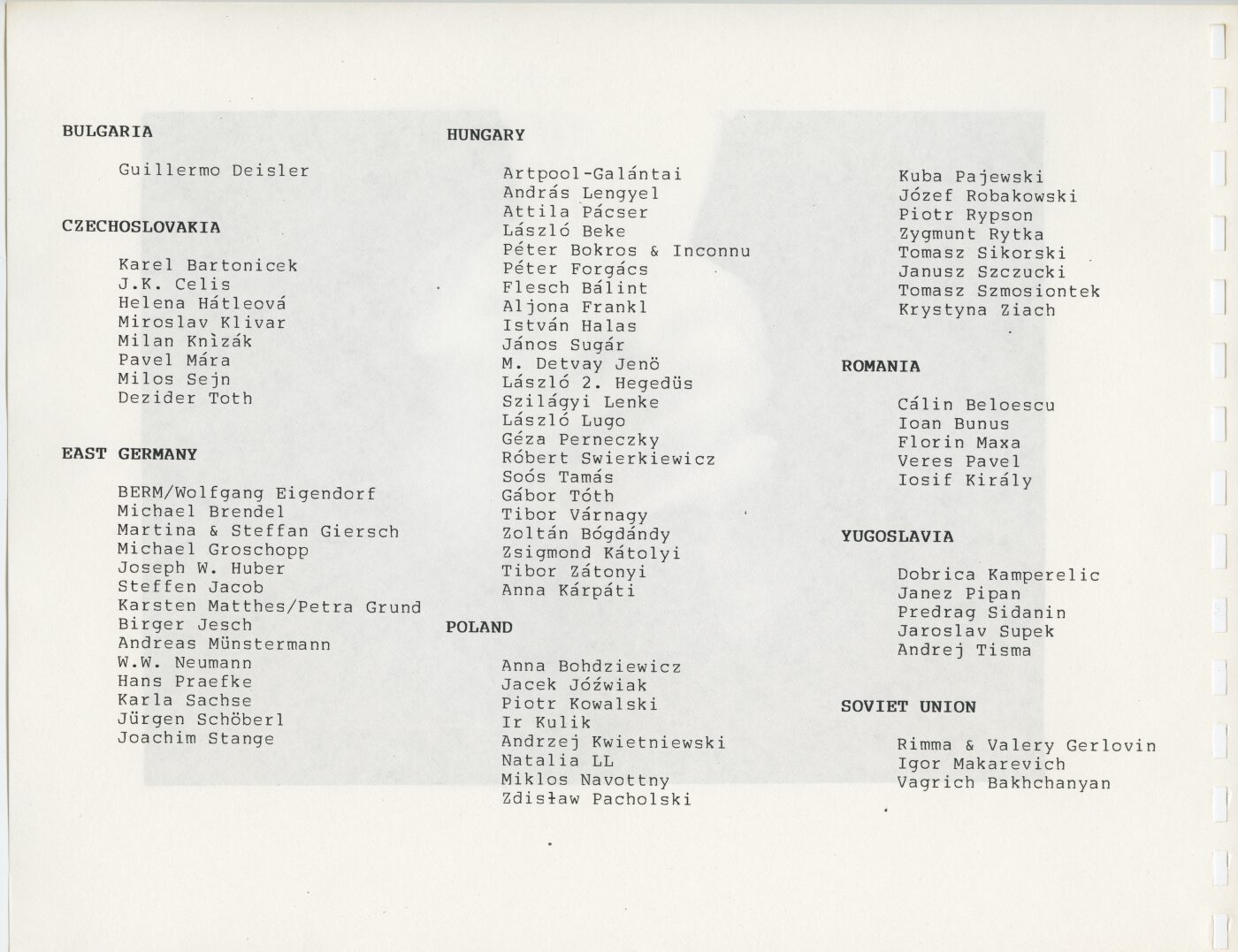

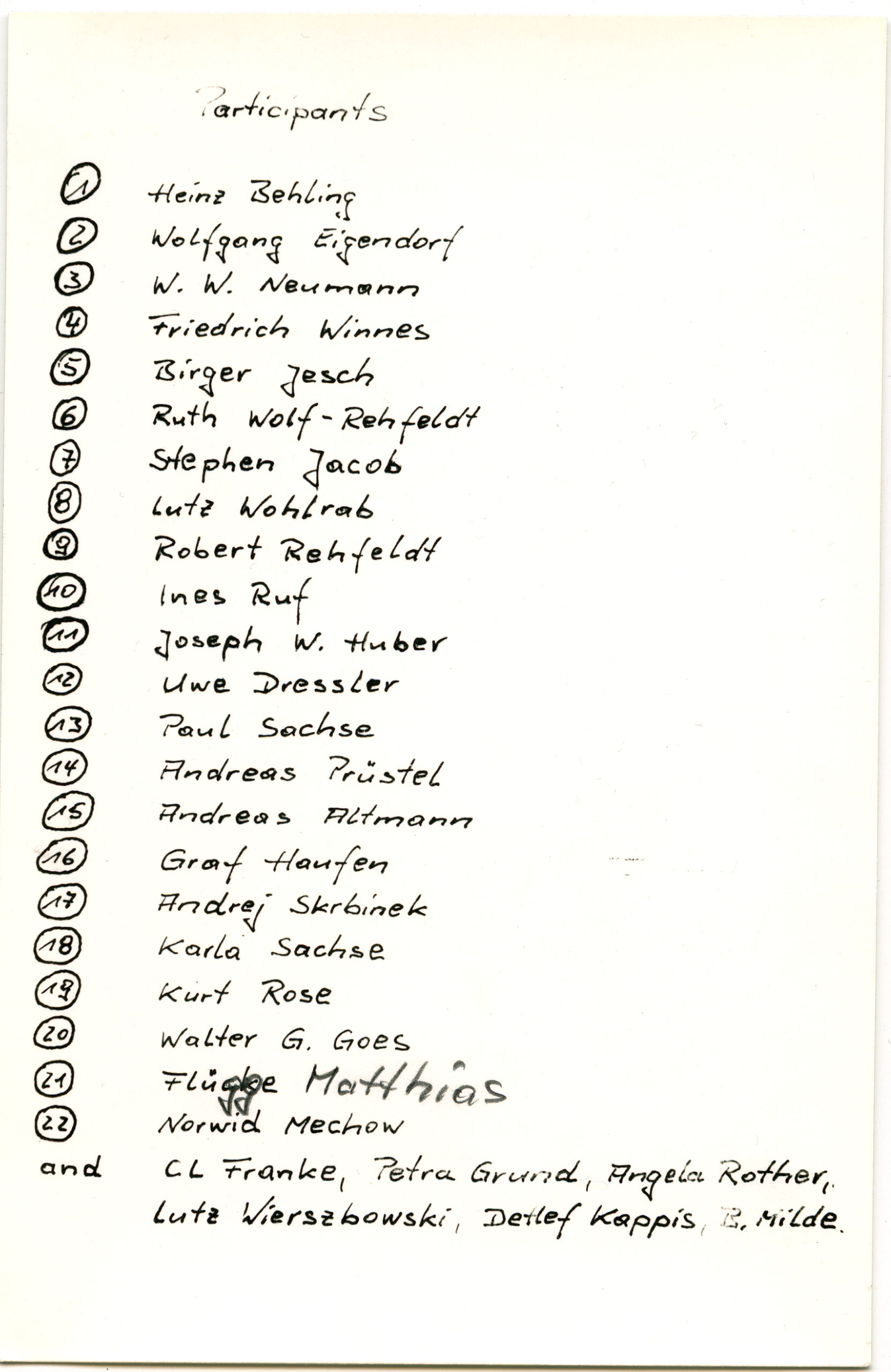

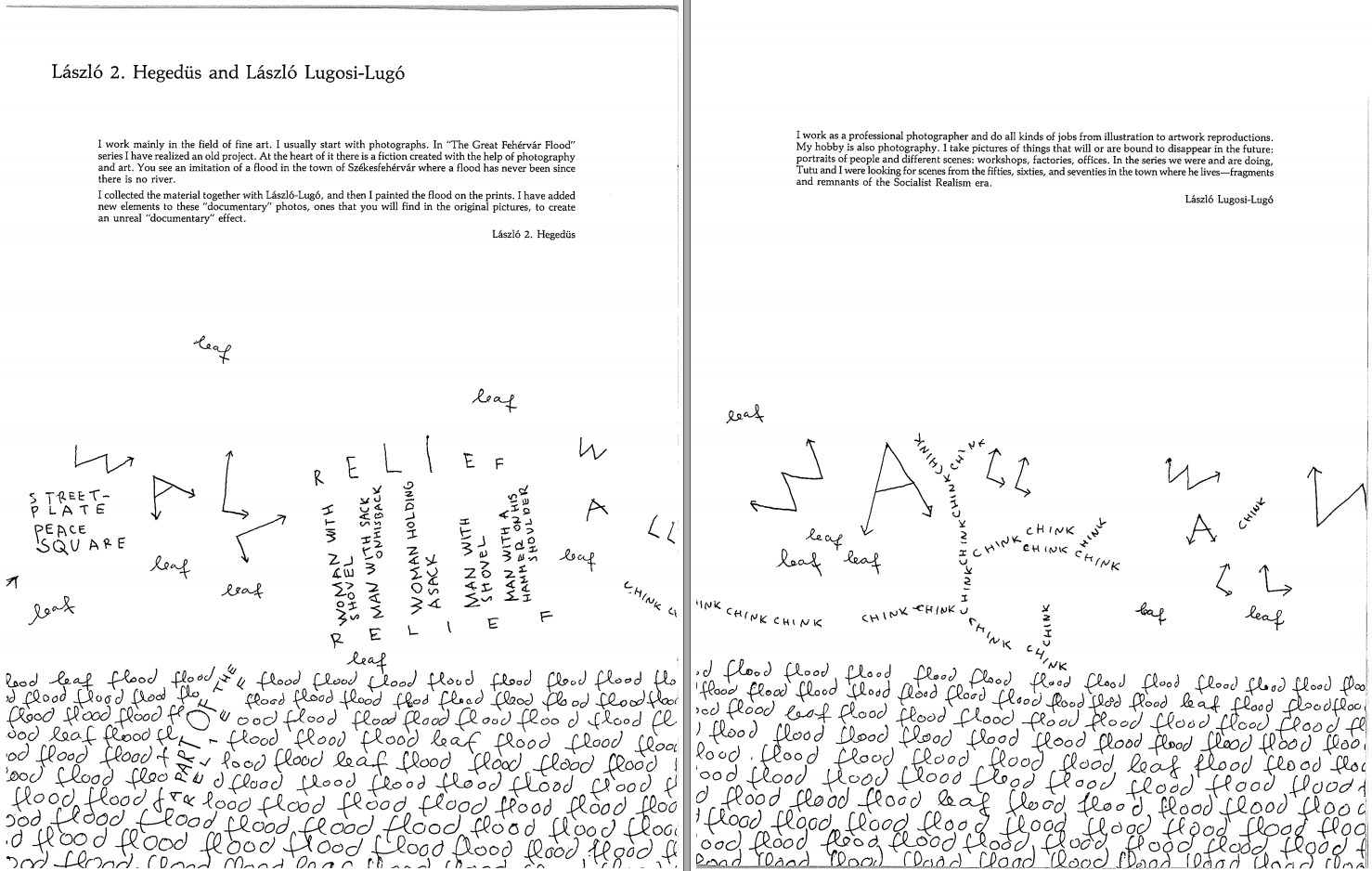

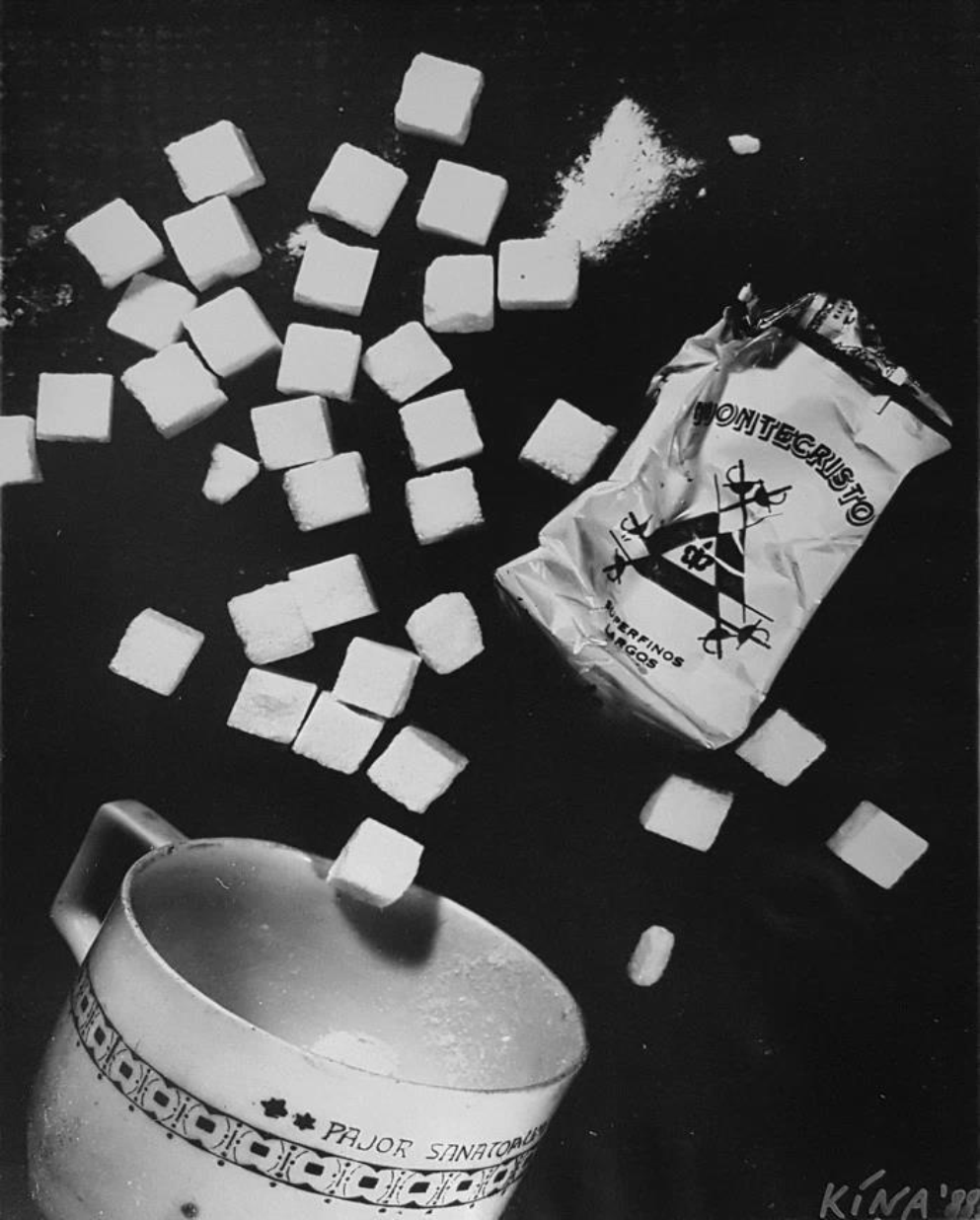

The exhibition included works by seventy-five artists from throughout Eastern Europe, one from the Soviet Union, and two Soviet emigre artists living in the US. The exhibition catalog, xerox-printed with a six-page gatefold of photographs by Polish artist Jozef Robakowski, contained an essay by Hungarian photographer Laszlo Lugosi-Lugo, and a co-authored text by Várnagy and Jacob. The catalog also included a disclaimer that the works presented were from the personal collection of the curator, and exhibited without the permission of the artists.

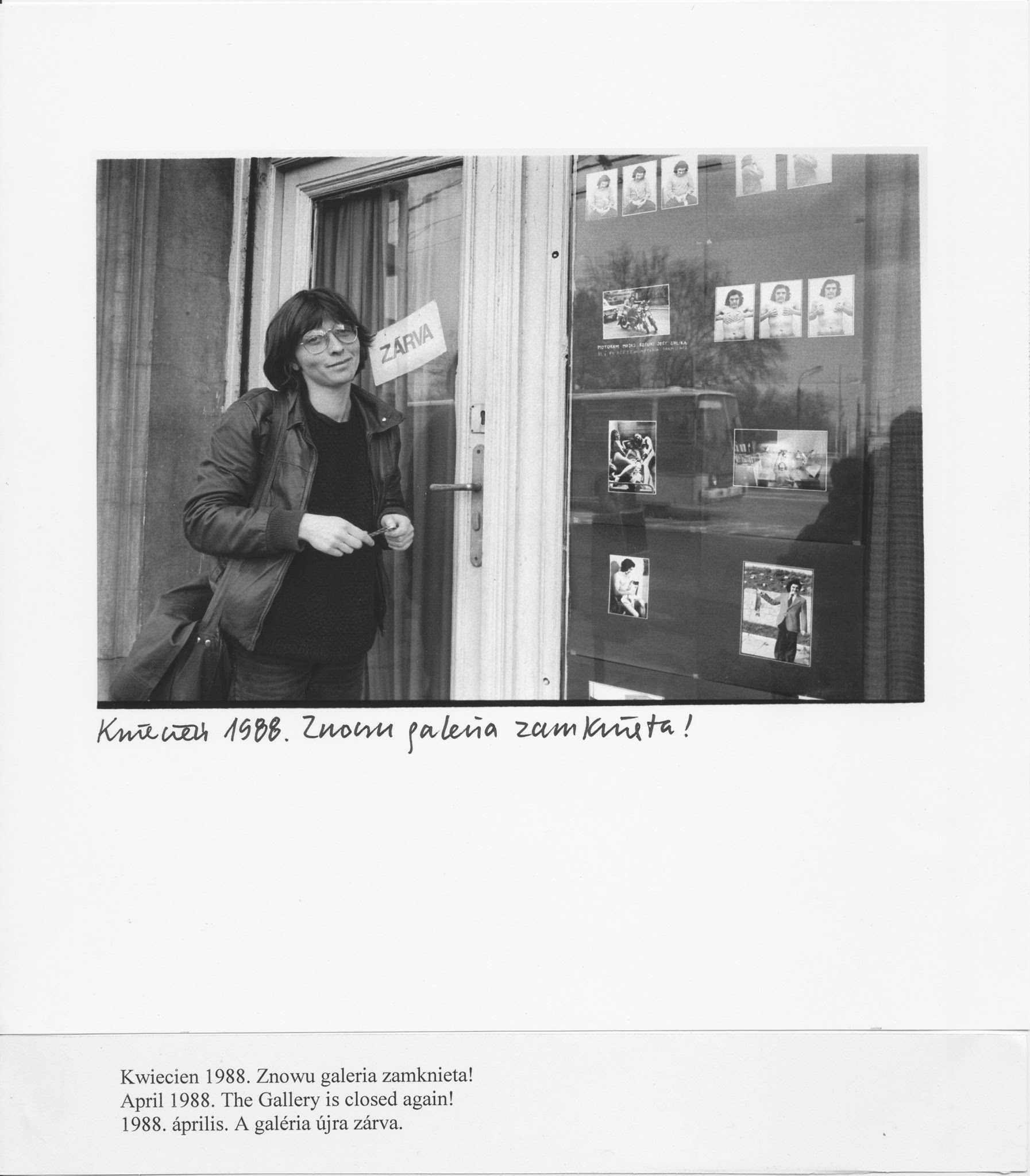

An address list of participants was circulated by Várnagy to the participants and among a small but expanding network of semi-official spaces. It simultaneously marked the existence of a parallel culture of photo-based artists working in Eastern Europe while contributing to the awareness of semi-independent spaces committed to presenting such work. Thus, the Second Portfolio exhibition set the stage for a series of increasingly adventurous international exchanges and events, including the exhibition of Milan Knizak’s Fire Prints and Jacob’s I am Trying to See at the Liget Galeria, and a long-term cooperation between the Liget and the Mala Galeria, the “little gallery” of the Polish Photographers’ Union, under the direction of Marek Grygiel, in Warsaw.

Second Portfolio, ed. Budapest (Open/Download PDF)

Contributors (by country):

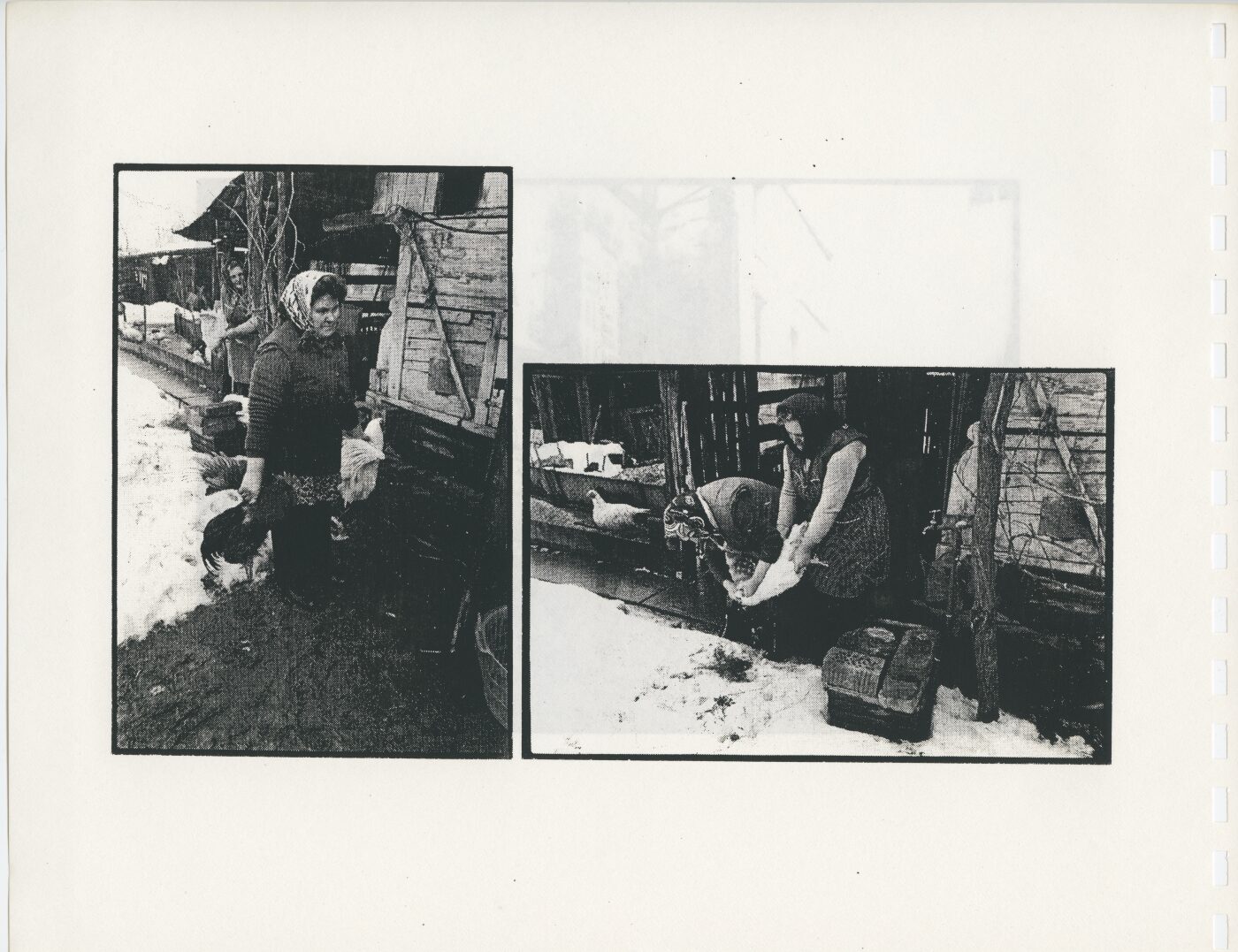

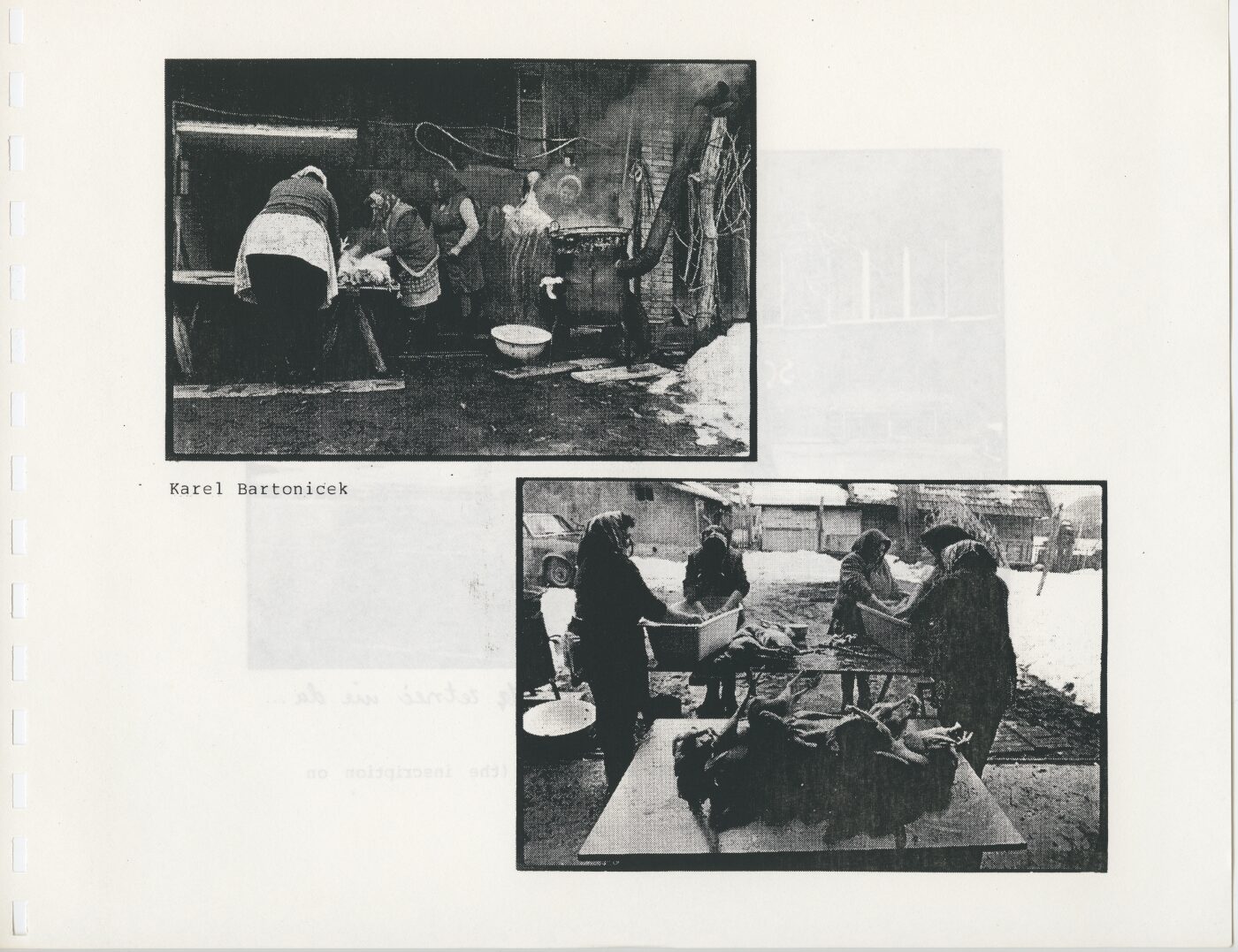

Bulgaria: Guillermo Deisler

Czechoslovakia: Karel Bartonicek; J.K. Celis; Helena Hátleová; Miroslav Klivar; Milan Knìzák; Pavel Mara; Silos Sejn; Dezider Toth

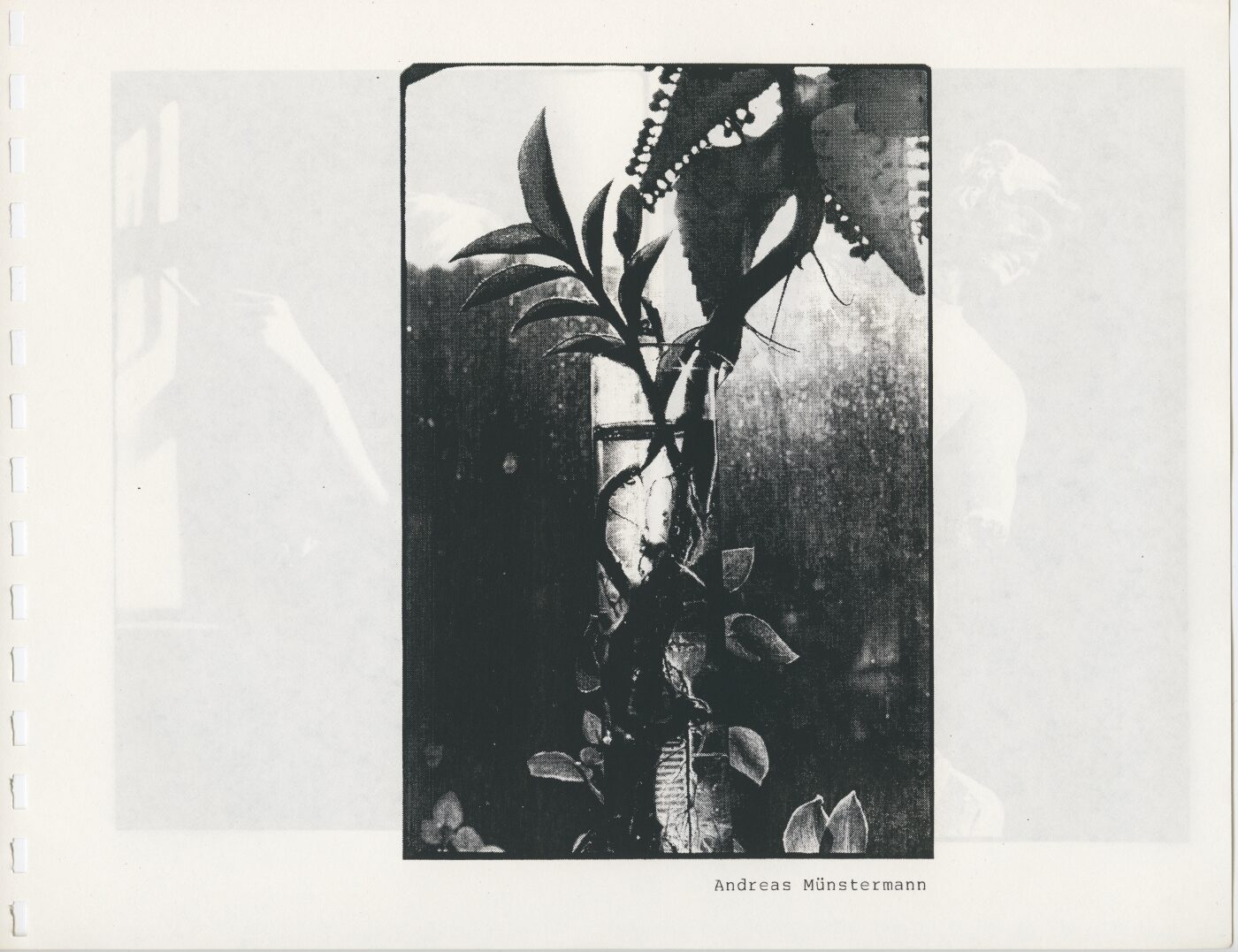

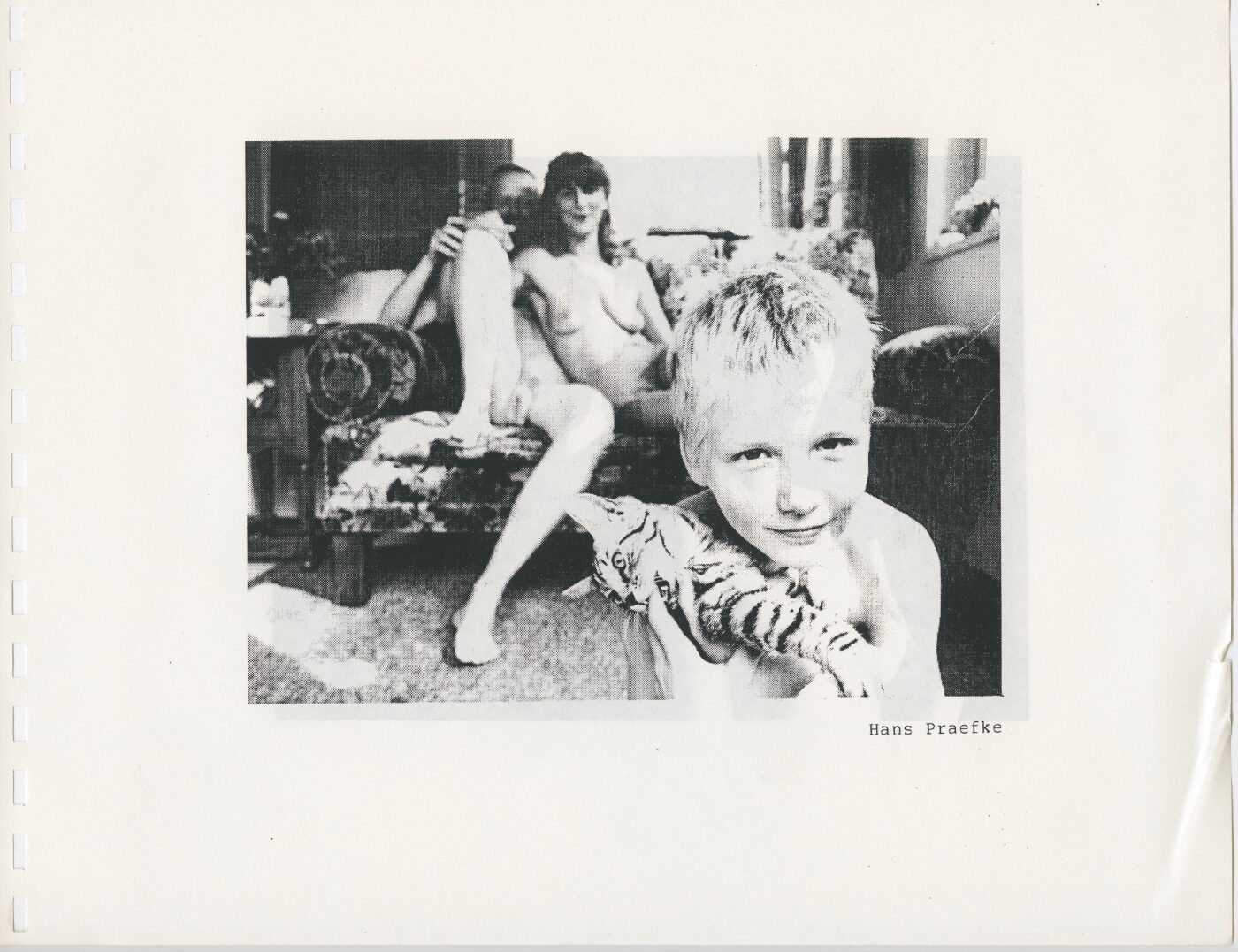

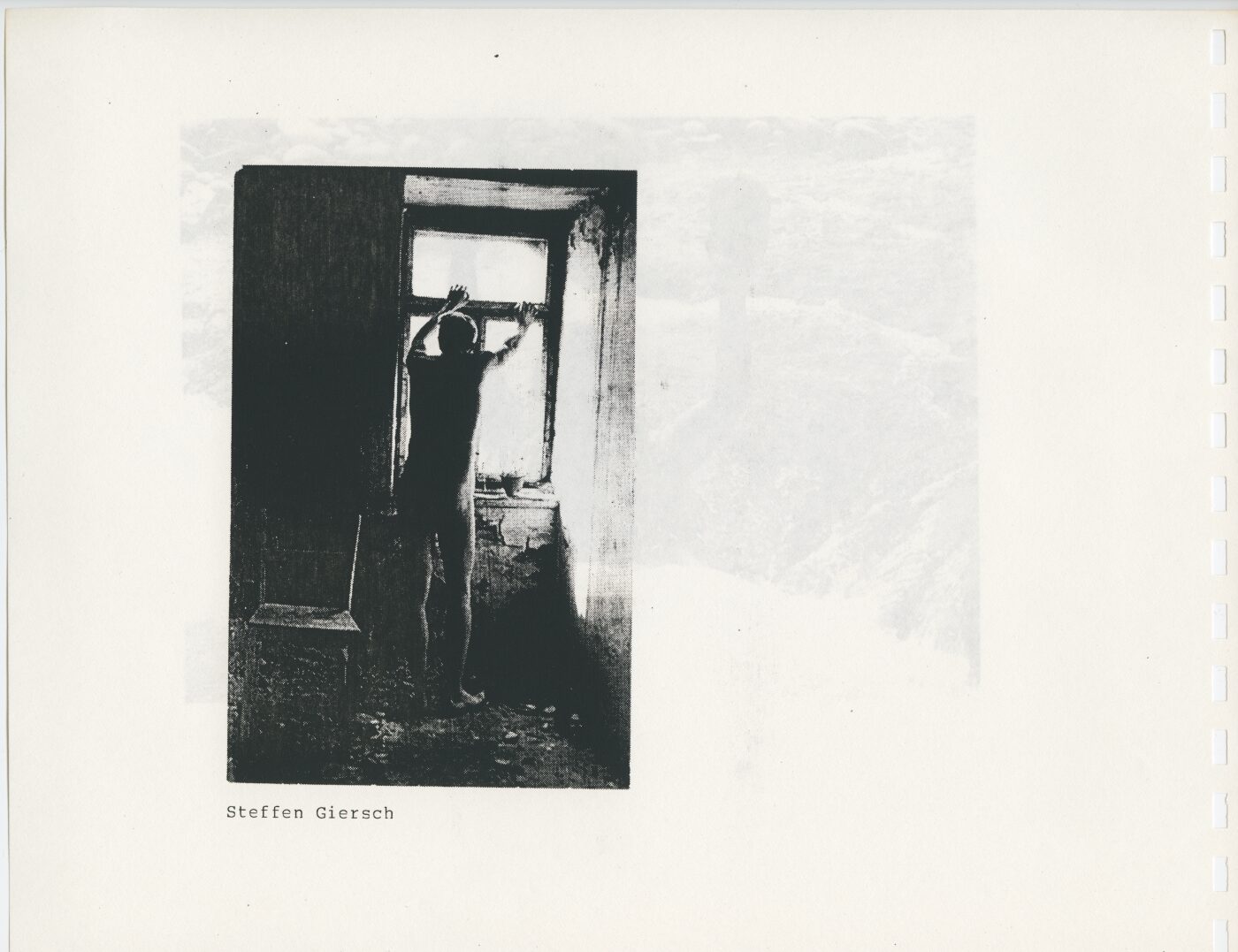

East Germany: BERM/Wolfgang Eigendorf; Michael Brendel; Martina & Steffan Giersch; Michael Groschopp; Joseph W. Huber; Steffen Jacob; Karsten Matthes & Petra Grund; Birger Jesch; Andreas Münstermann; W.W. Neumann; Hans Praefke; Karla Sachse; Jurgen Schöberl; Joachim Stange

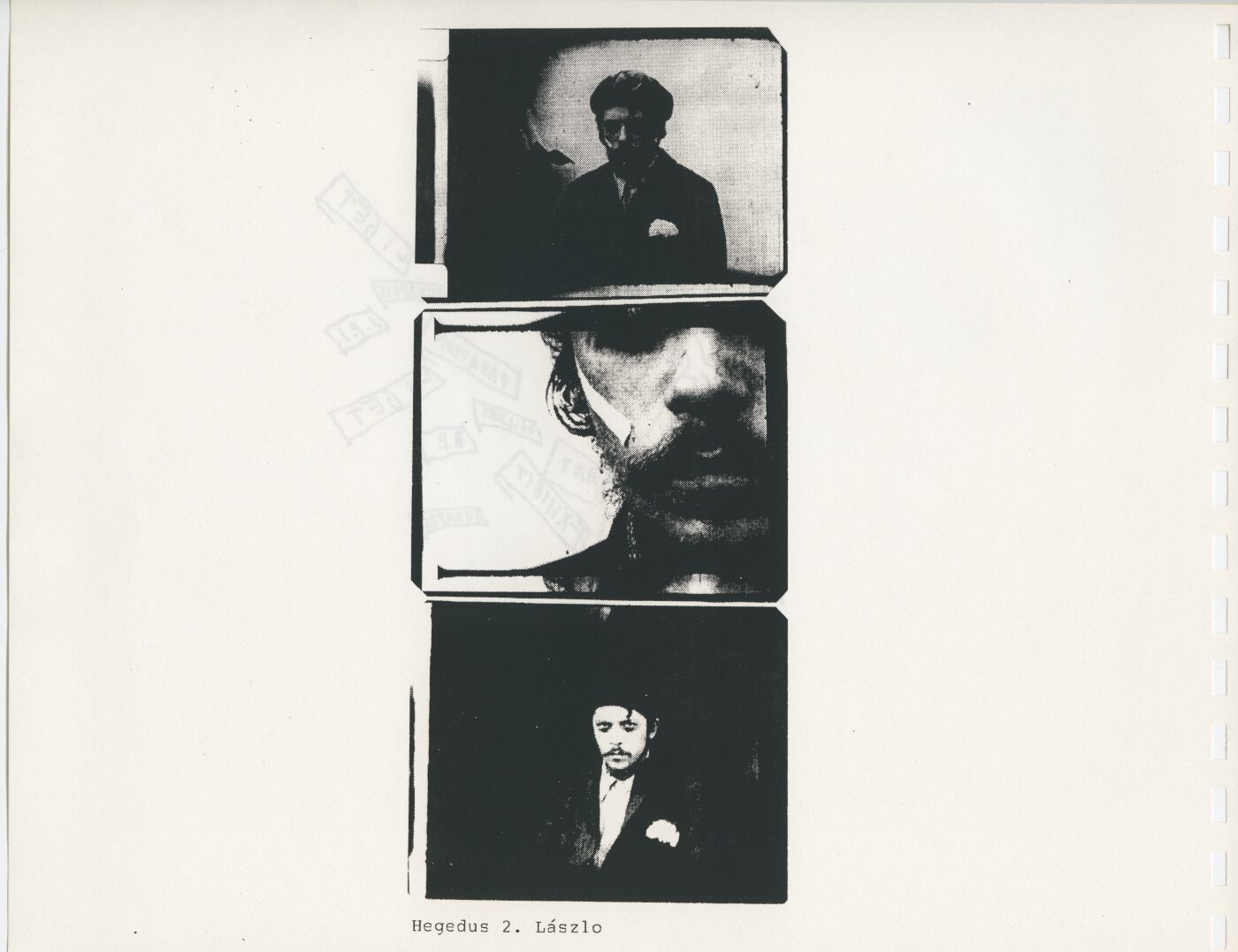

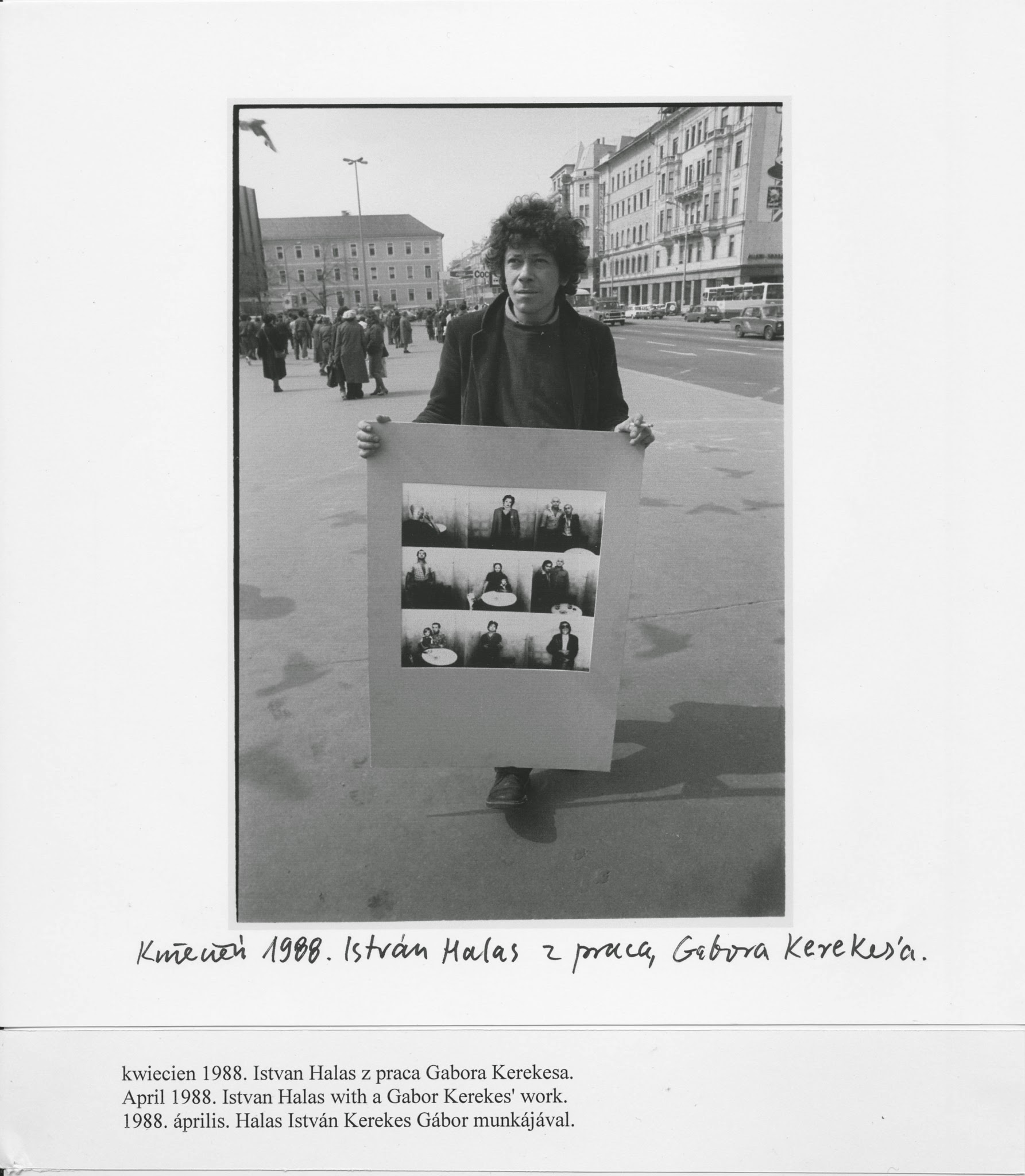

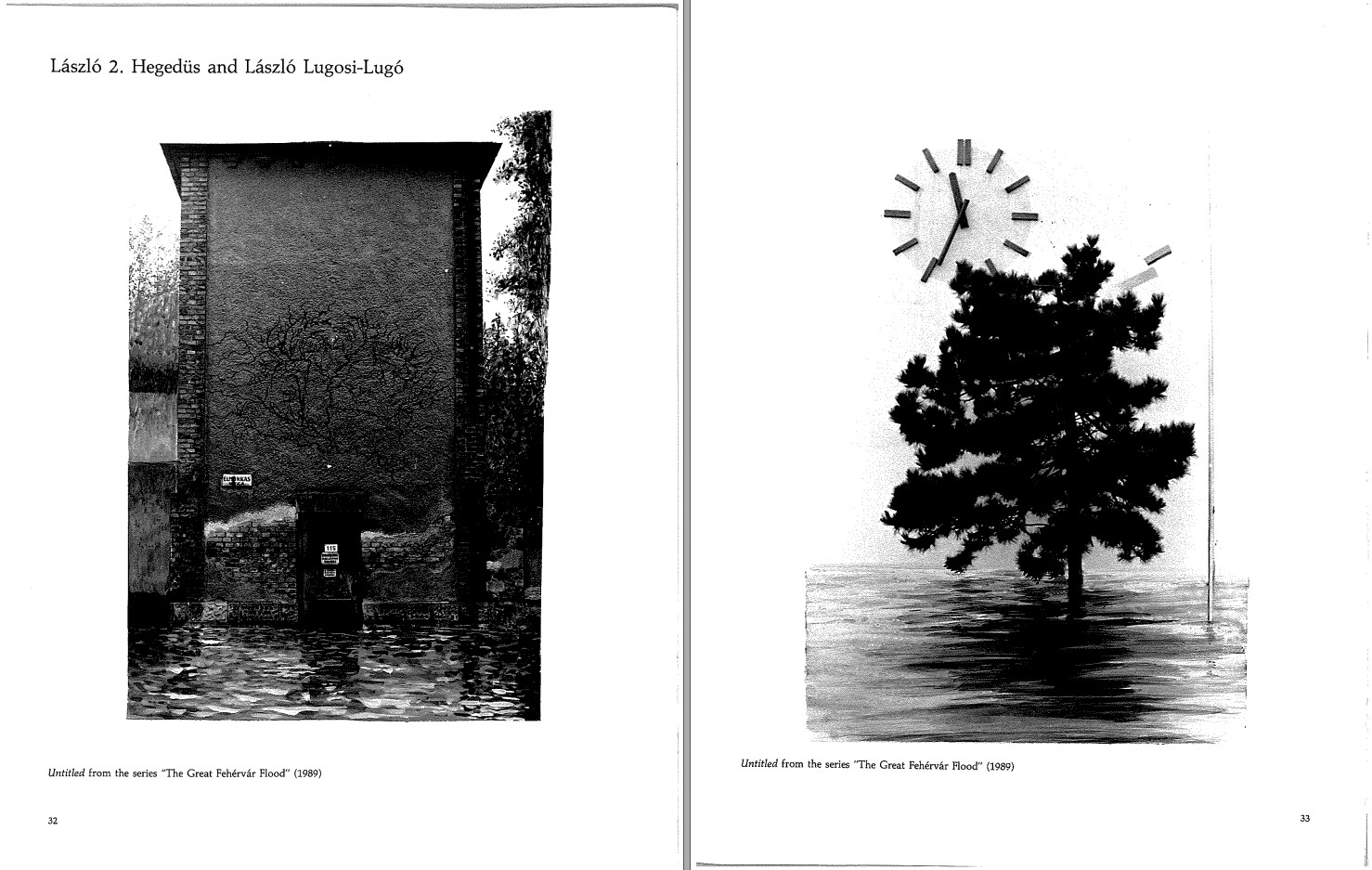

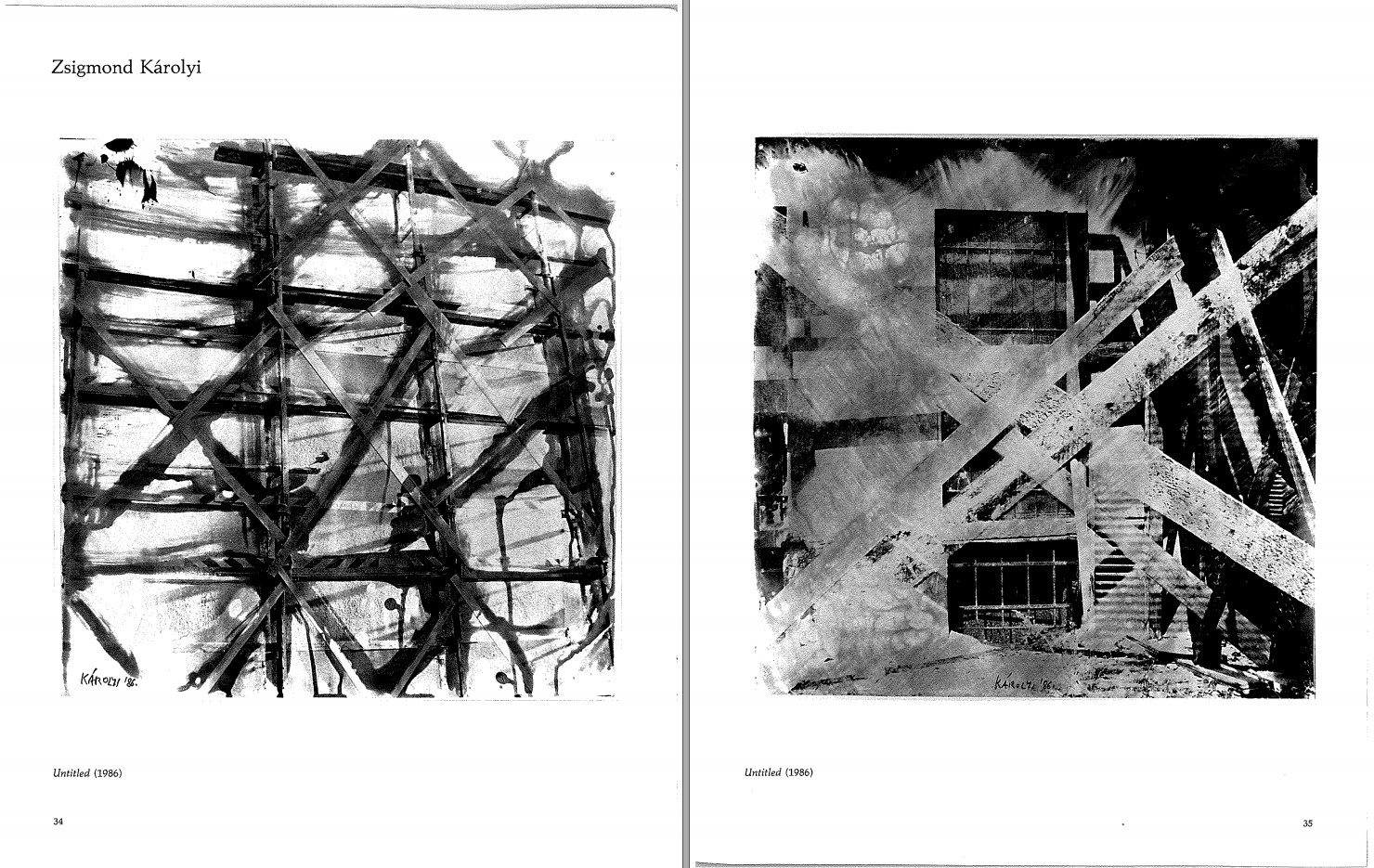

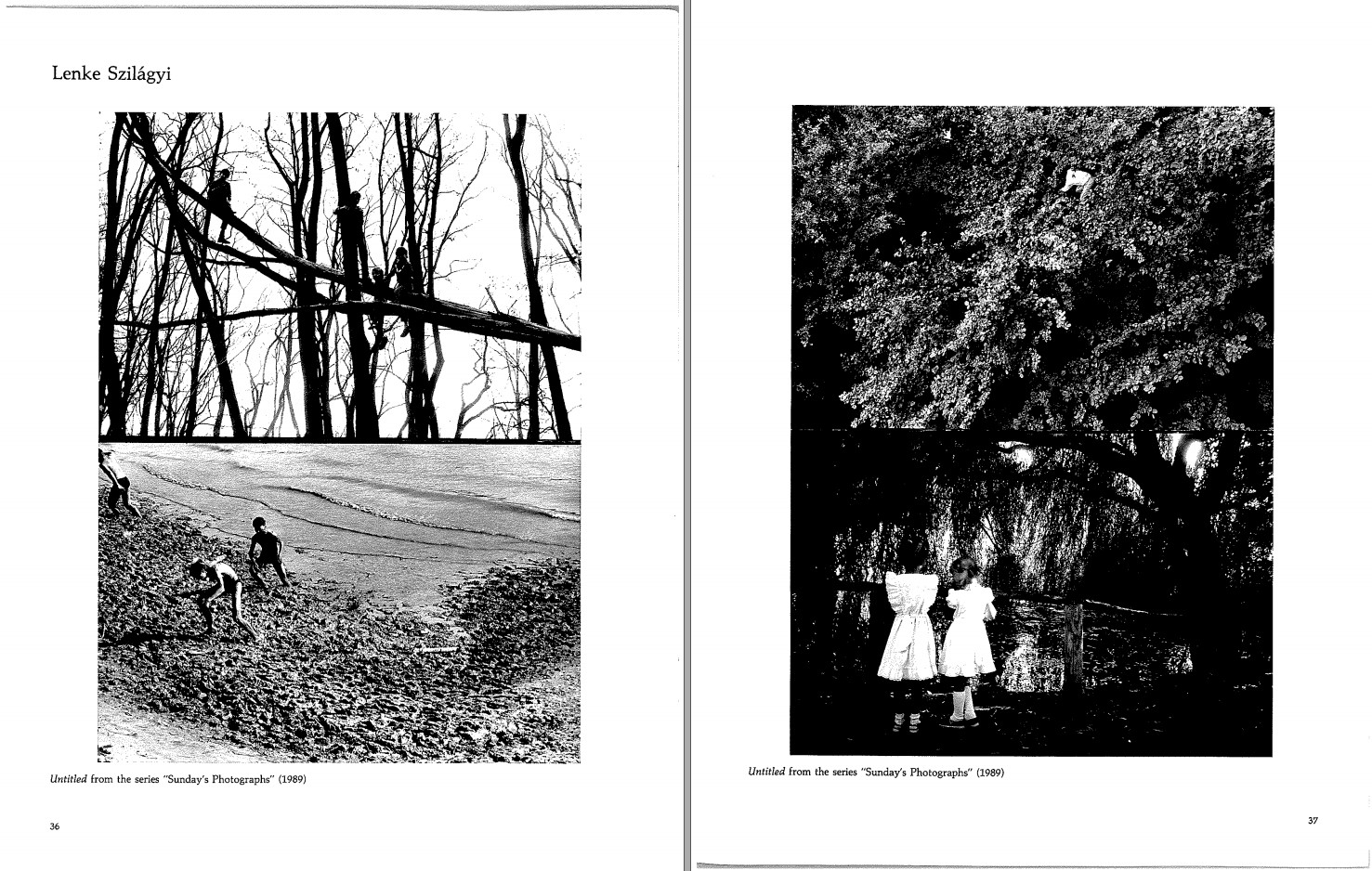

Hungary: Artpool/Galantái; András Lengyel; Atilla Pácser; László Beke; Péter Bokros & Inconnu; Péter Forgács; Flesch Bálint; Aljona Frankl; István Halas; János Sugár; M. Detvay Jenö; László 2. Hegedüs; Szilágyi Lenke; László Lugosi-Lugo; Géza Perneczky; ; Róbert Swierkiewicz; Soós Tamas; Gábor Tóth; Tibor Várnagy; Zoltán Bógdandy; Zsigmond Károlyi; Tibor Zátonyi; Anna Kárpáti

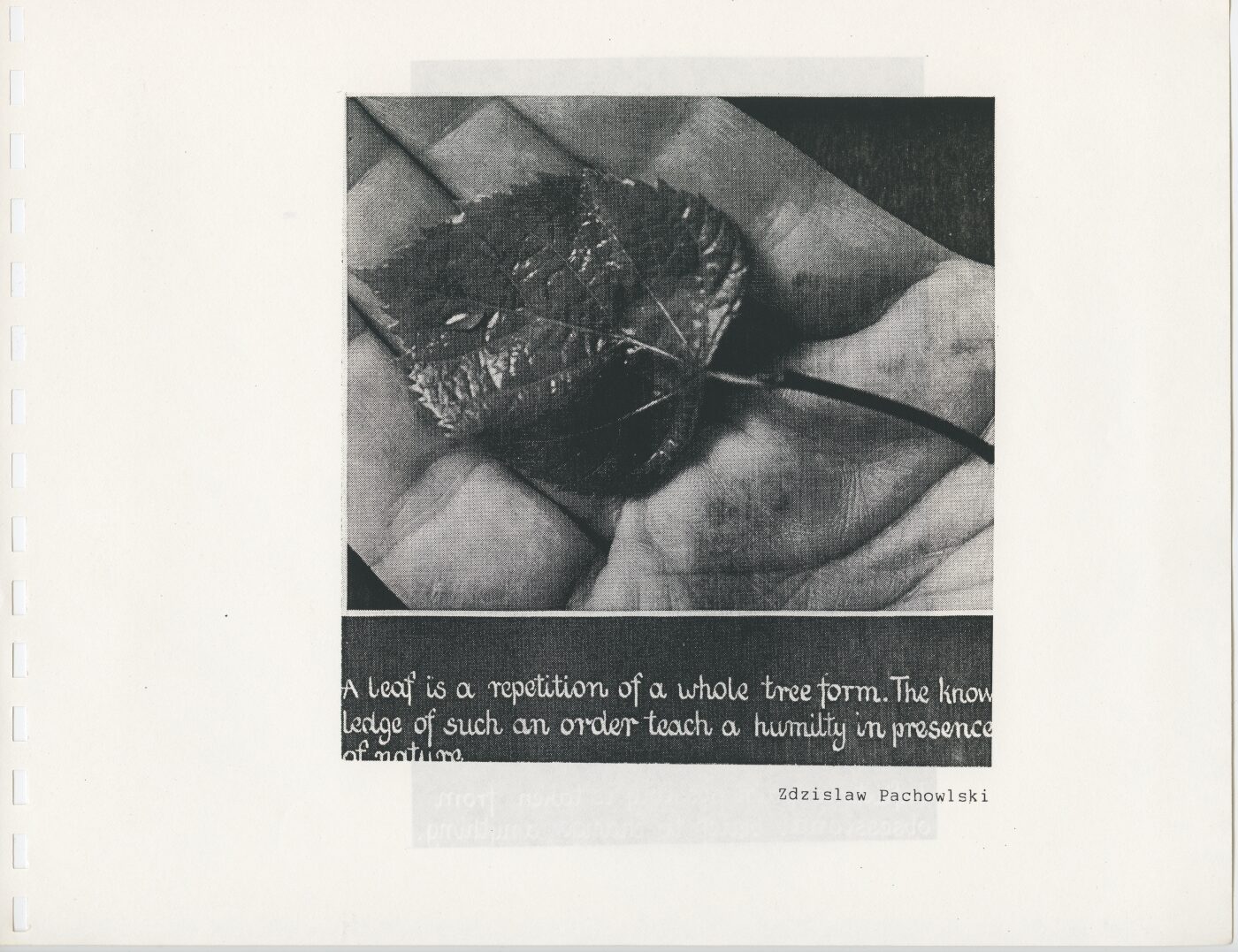

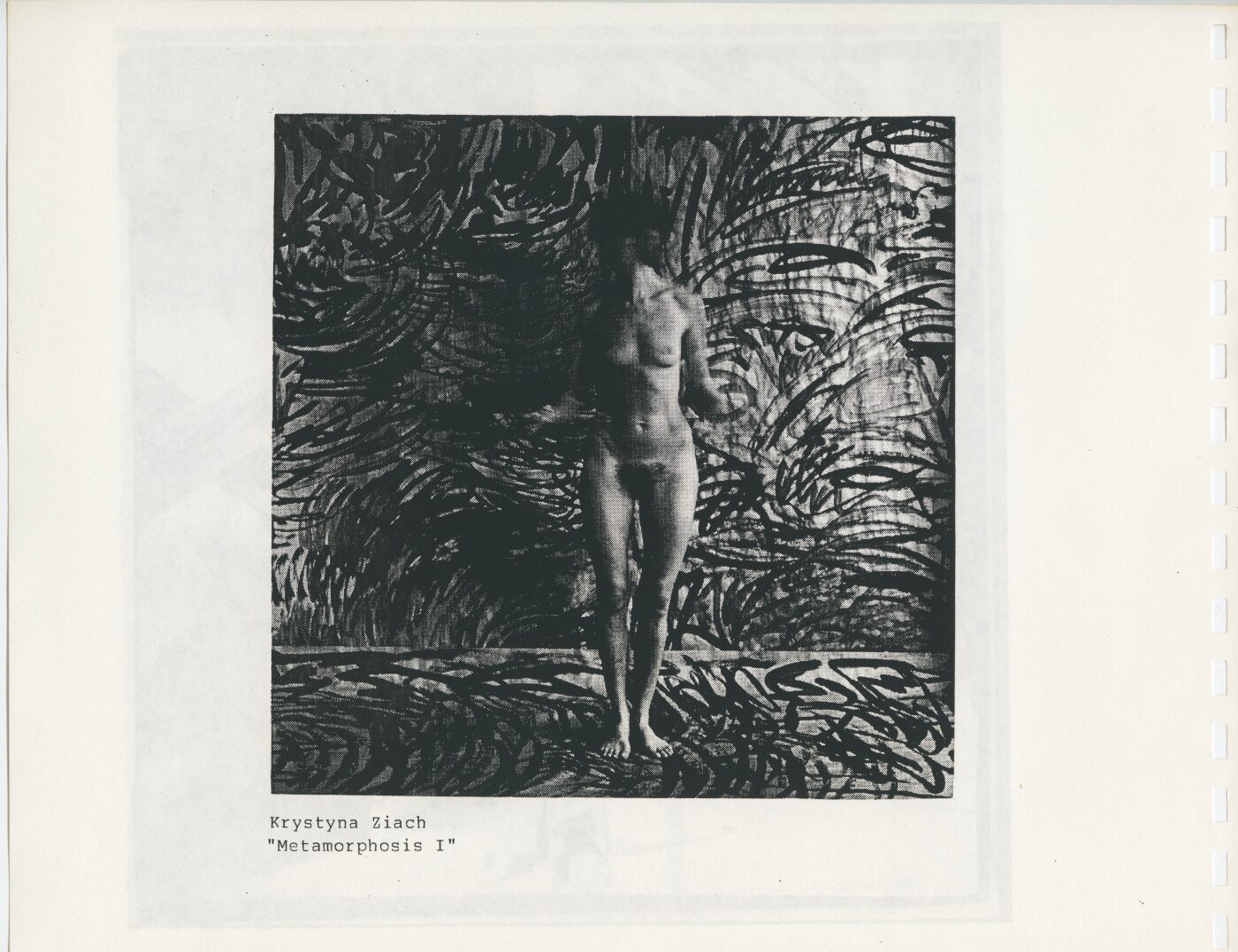

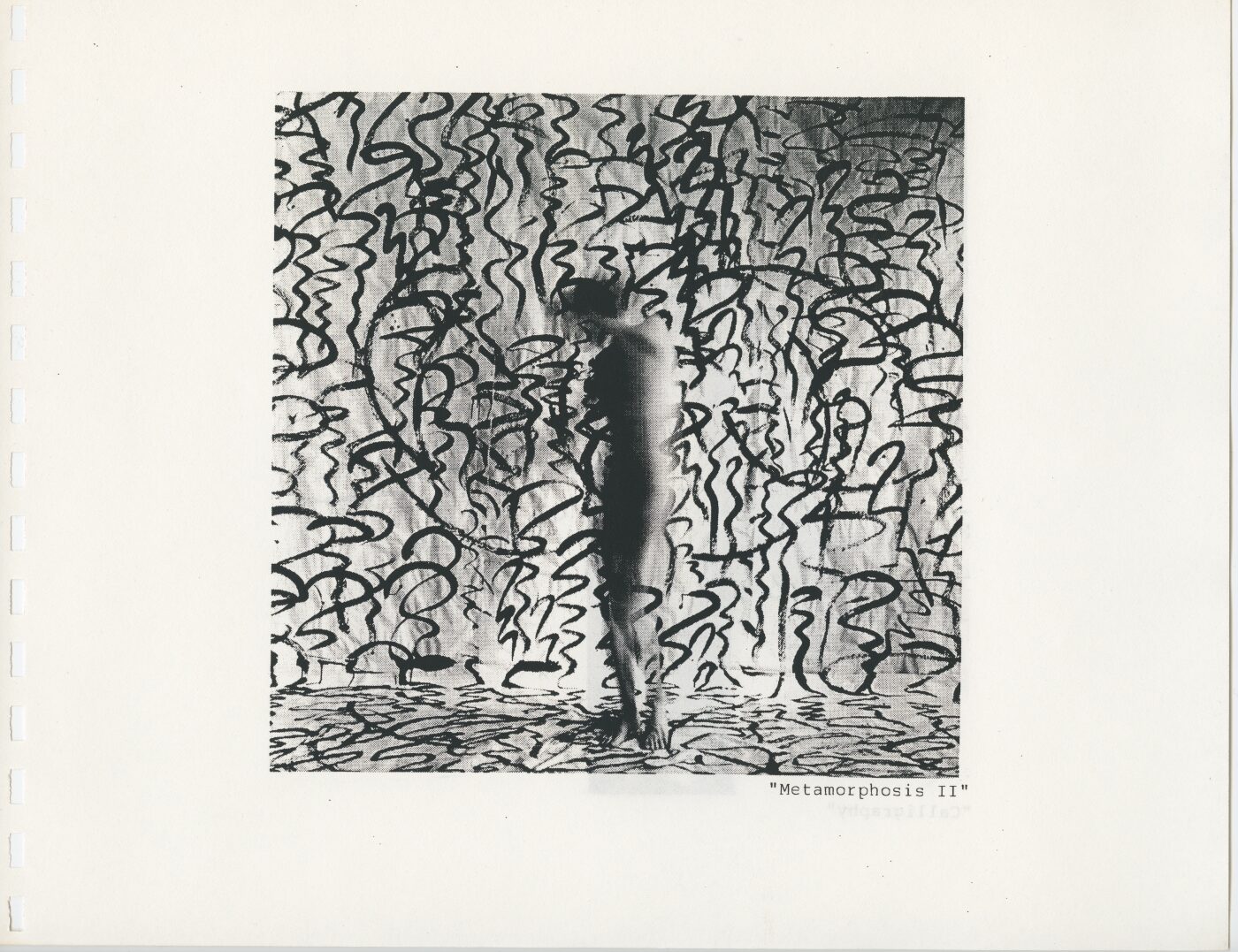

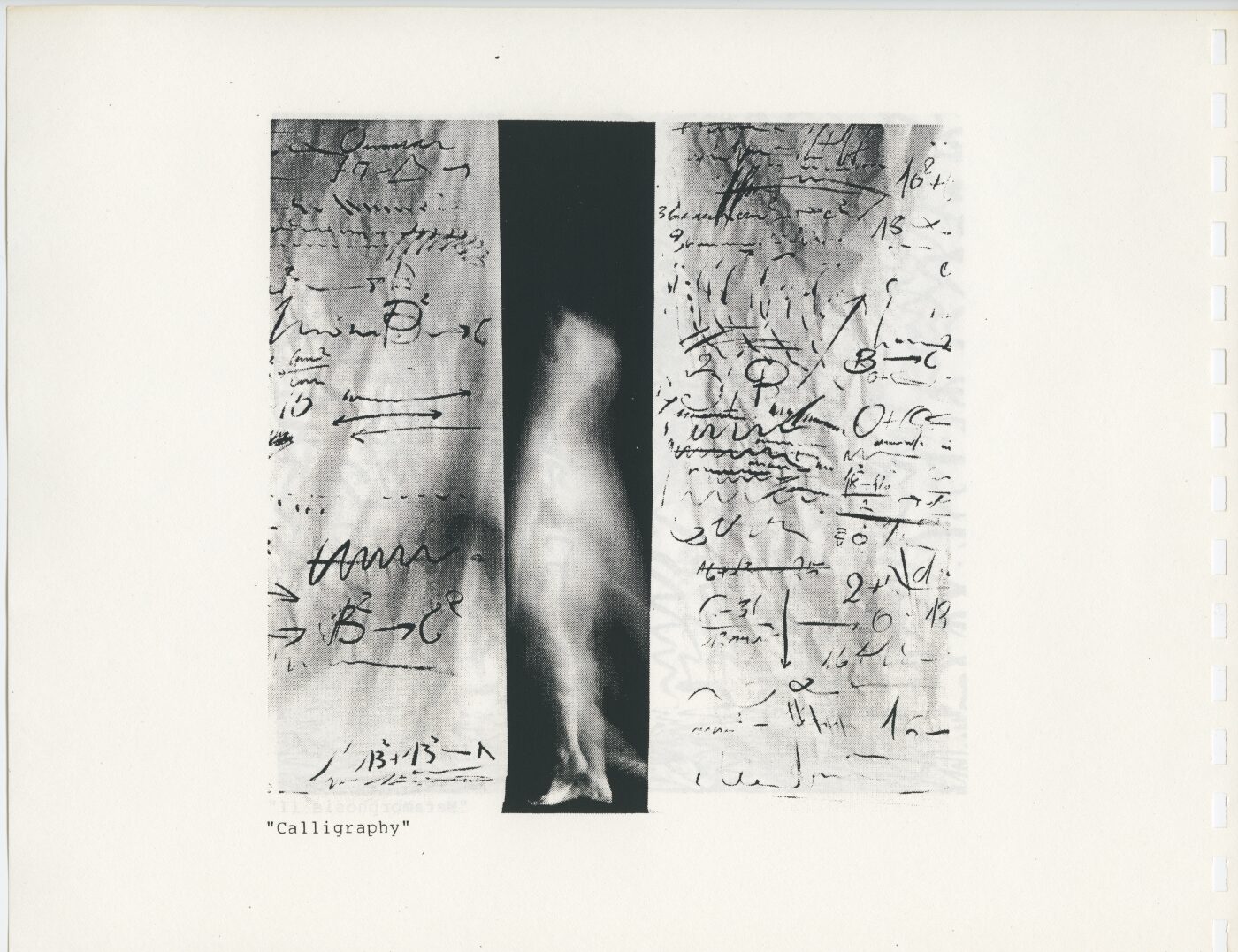

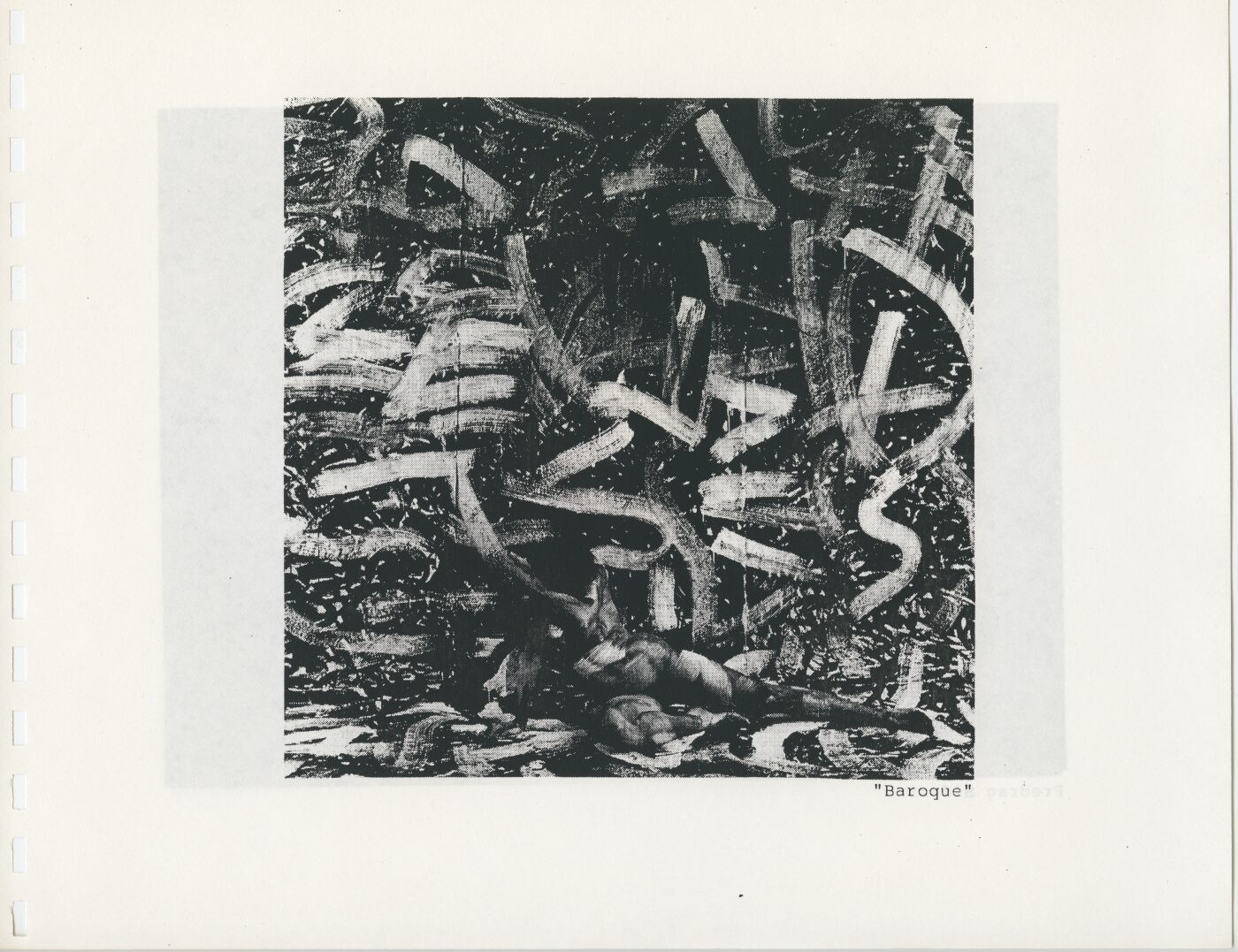

Poland: Anna Bohdziewicz; Jacek Józwiak; Piotr Kowalski; Ir Kulik; Andrzej Kwietniewski; Natalia LL; Miklos Novottny; Zdlislaw Pacholski; Kuba Pajewski; Józef Robakowski; Piotr Rypson; Zygmunt Rytka; Tomasz Sikorski; Janusz Szczucki; Tomasz Szmosiontek; Krystyna Ziach

Romania: Cálin Beloescu; Ioan Bunus; Florin Maxa; Veres Pavel; Iosif Eiraly

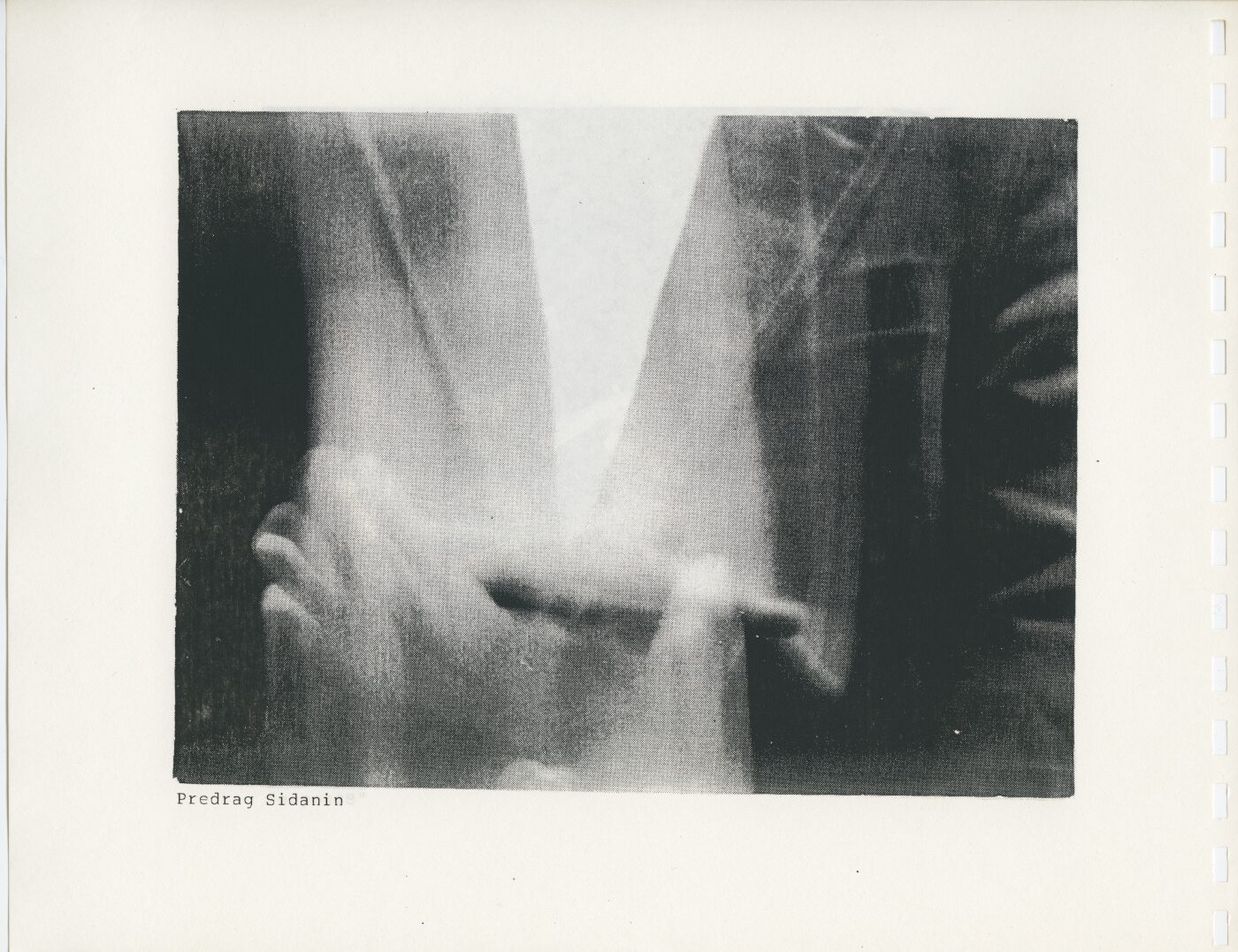

Yugoslavia: Dobrica Kampereelic; Janez Pipan; Predag Sidanin; Jaroslav Supek; Andrej Tisma

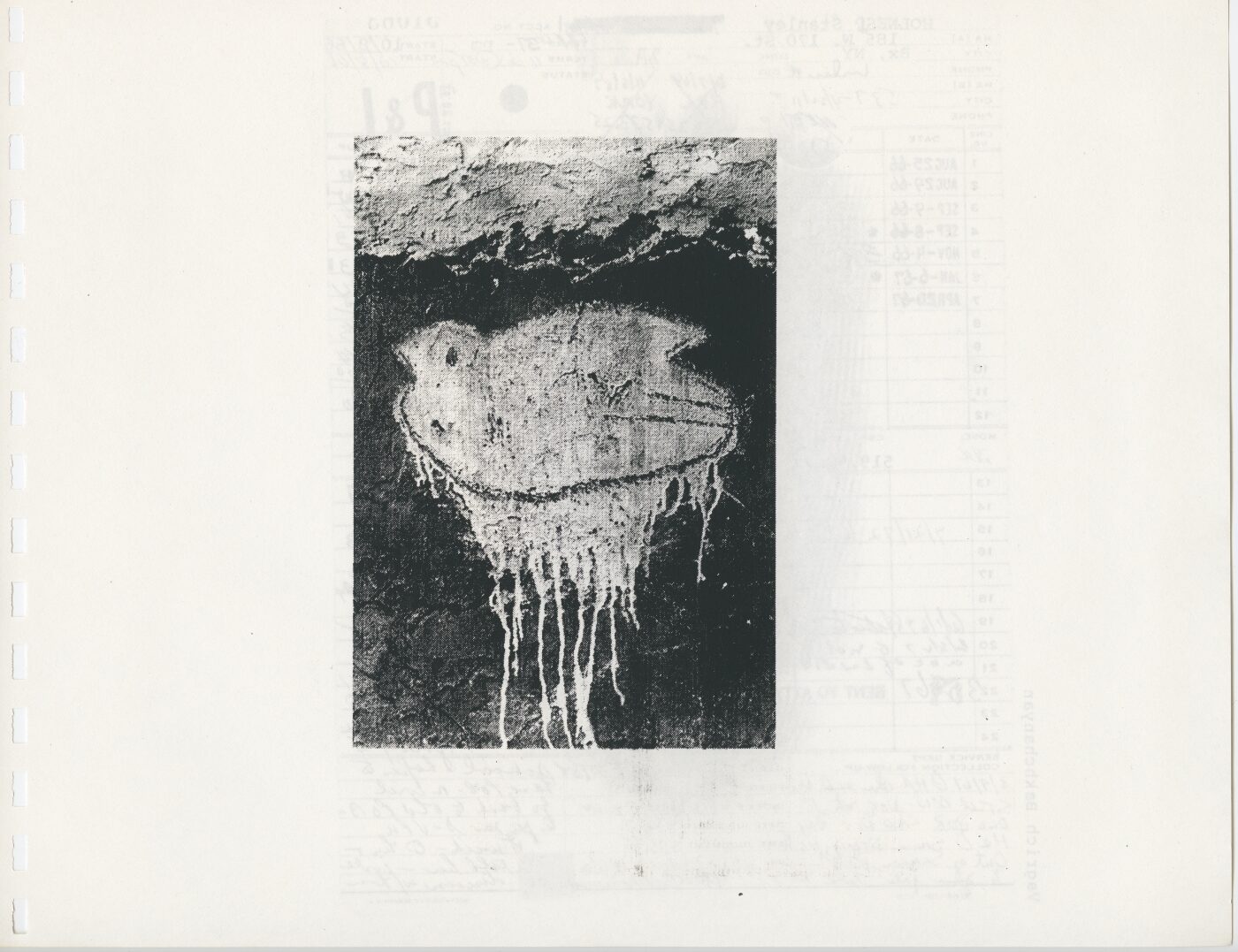

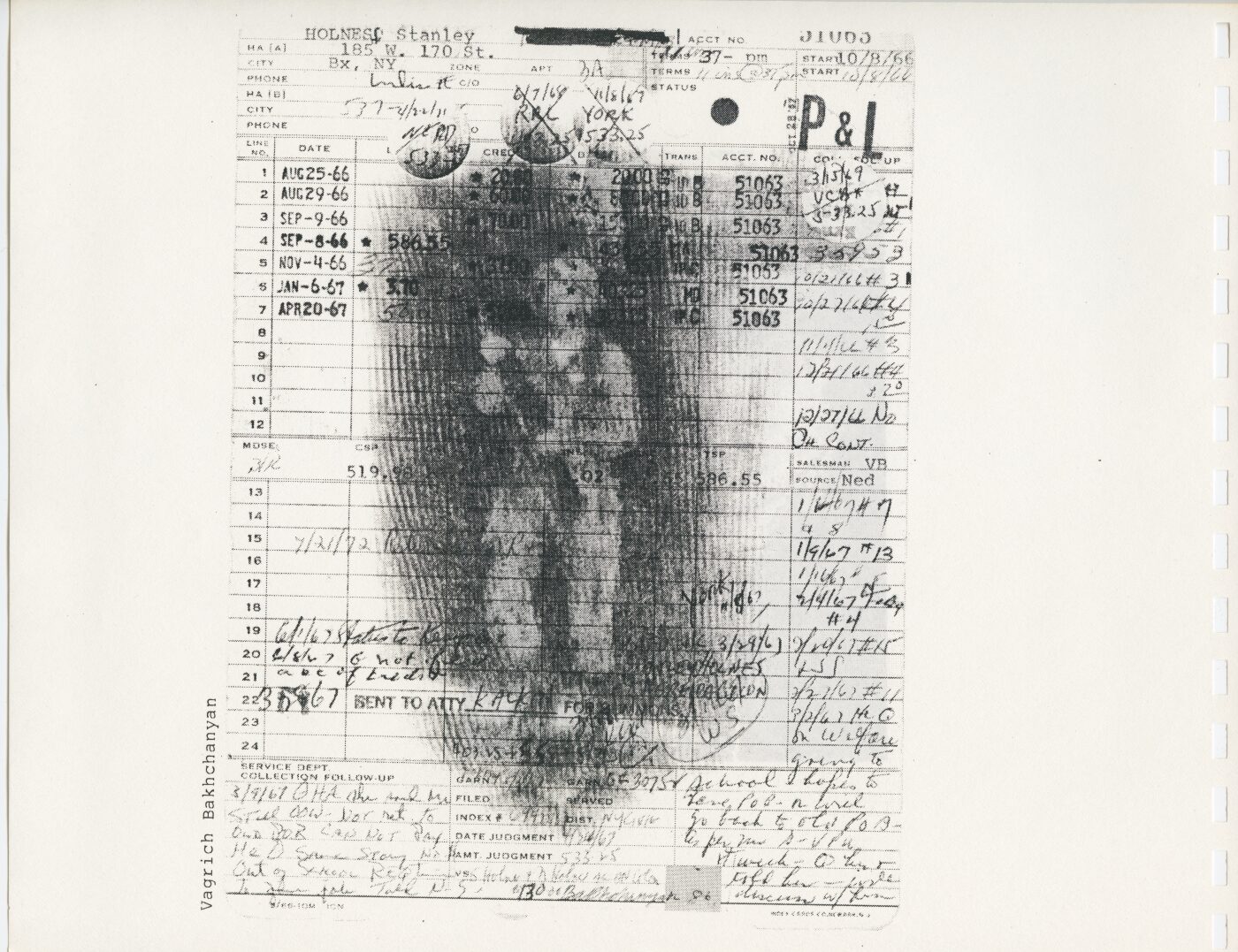

USSR: Rimma & Valeriy Gerlovin; Igor Makarevich; Vagrich Bakhchanyan

Liget Gallery page:

http://www.ligetgaleria.c3.hu/dupla8390.htm

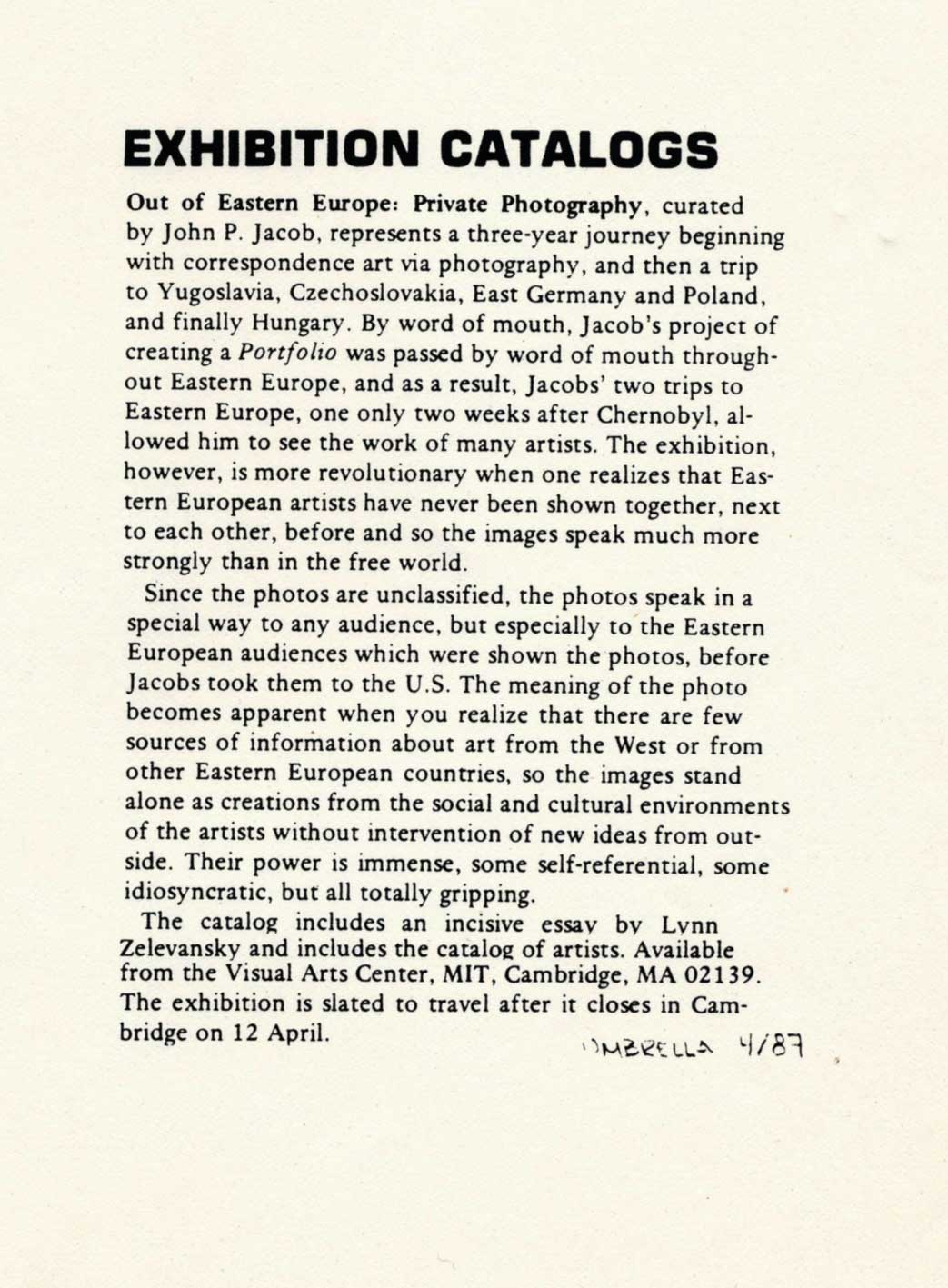

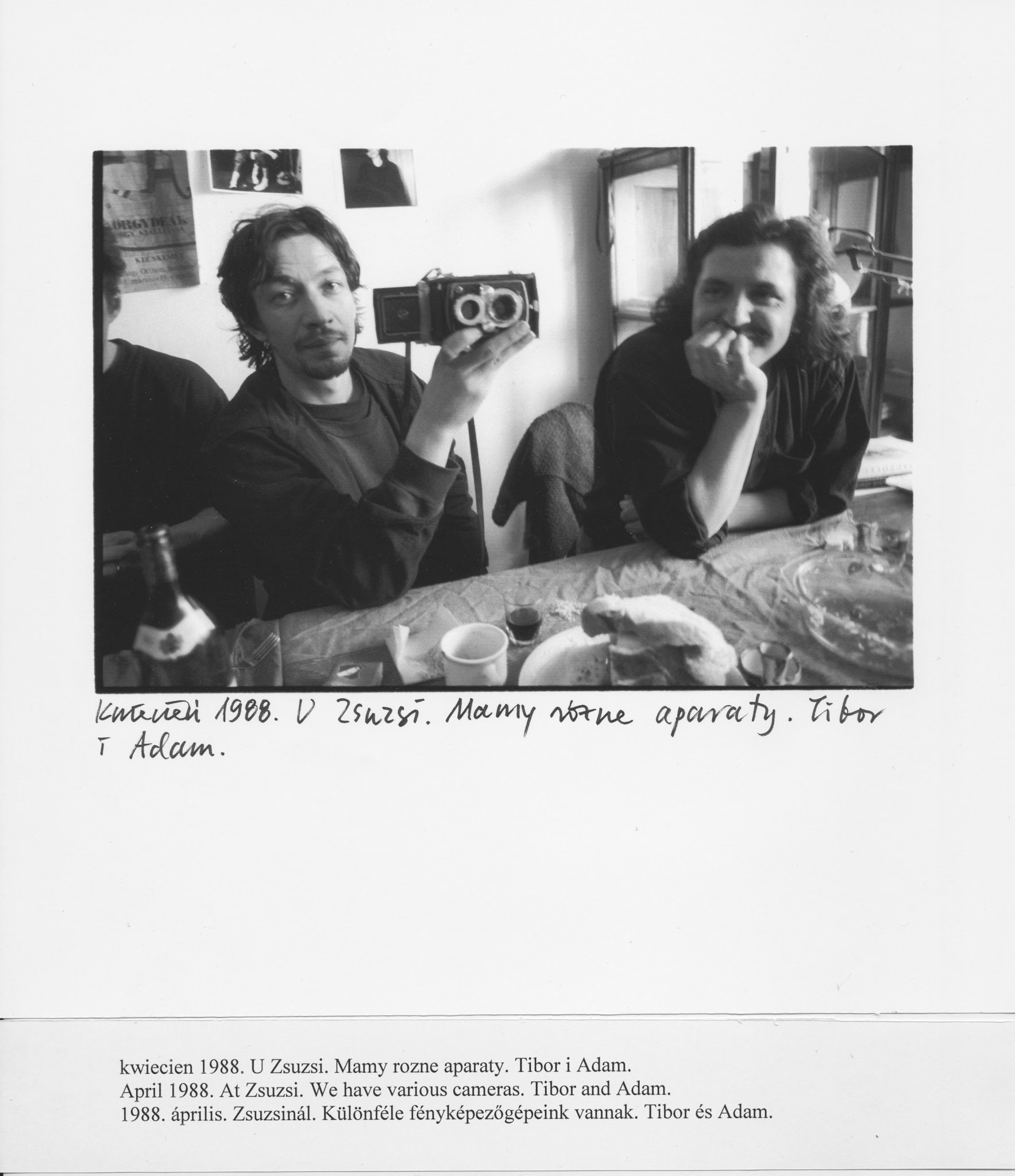

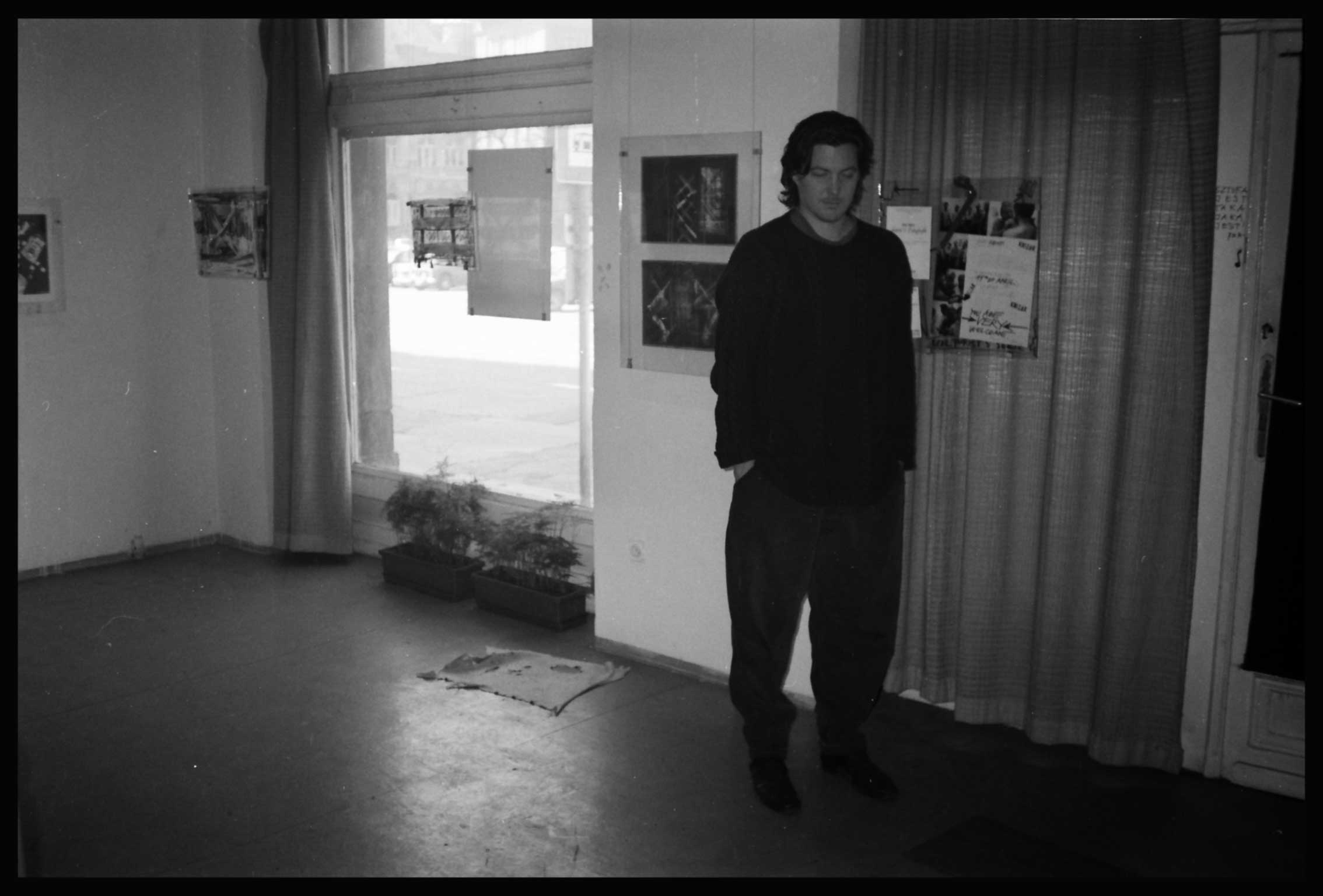

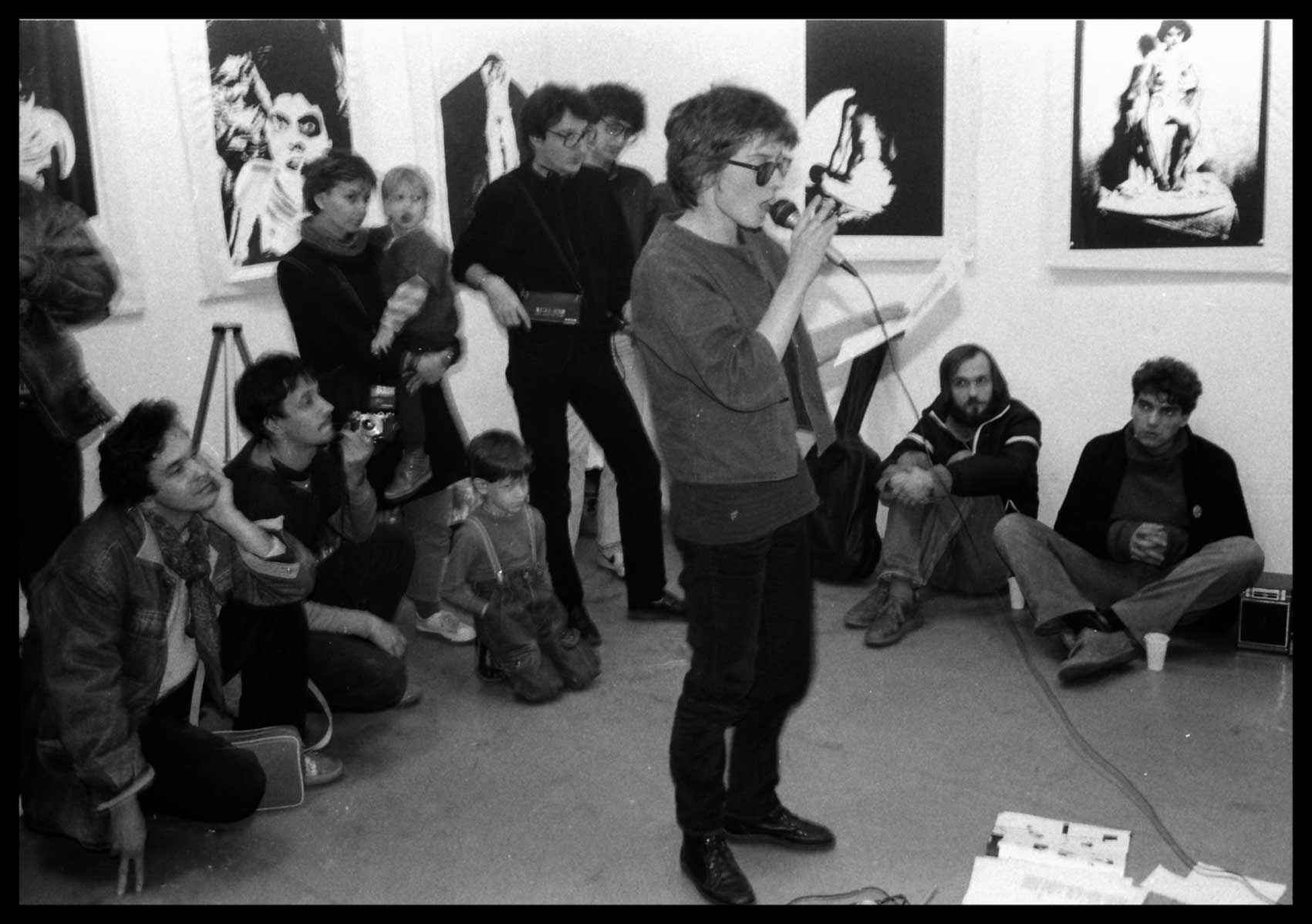

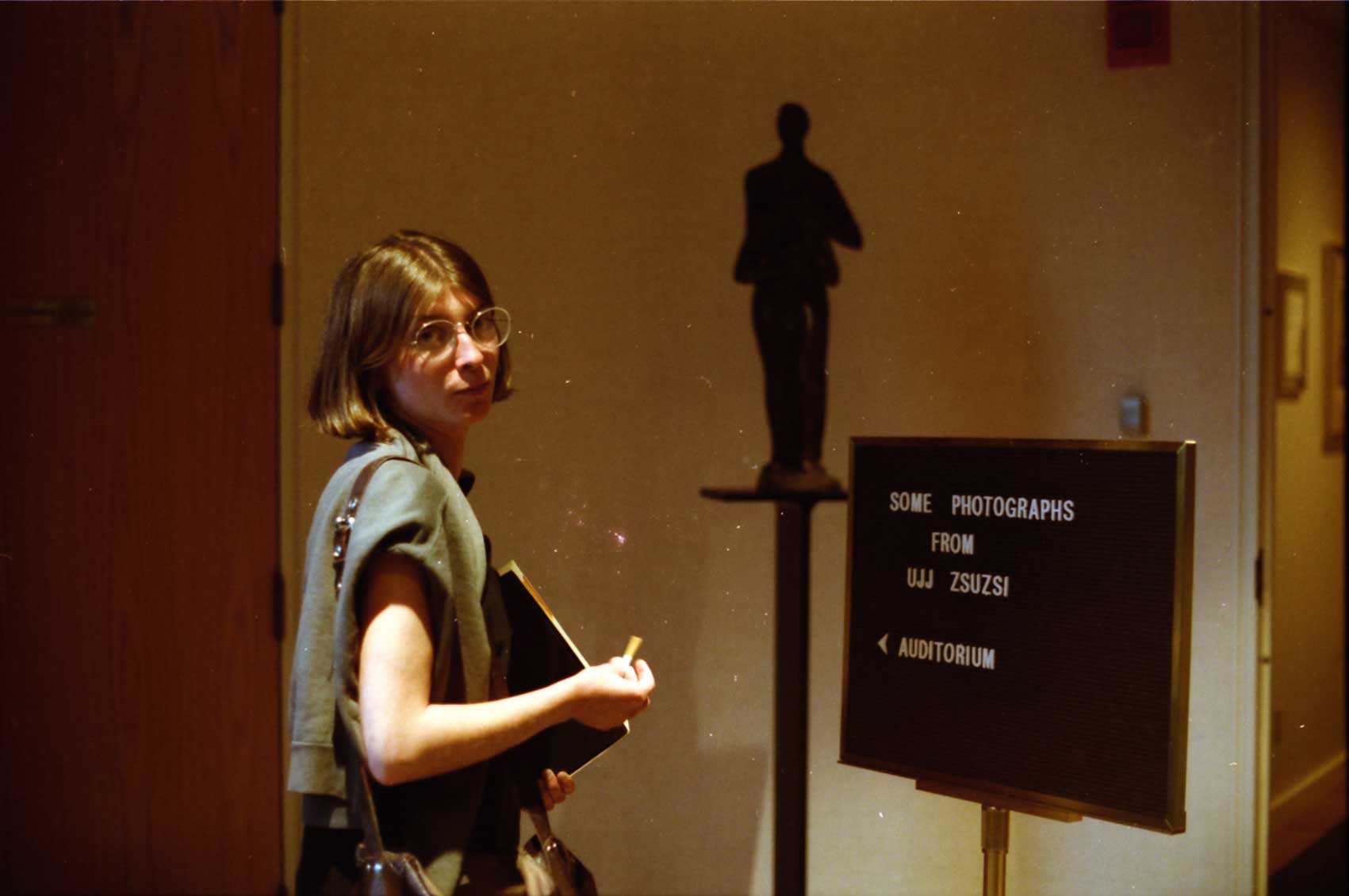

Out of Eastern Europe: Private Photography

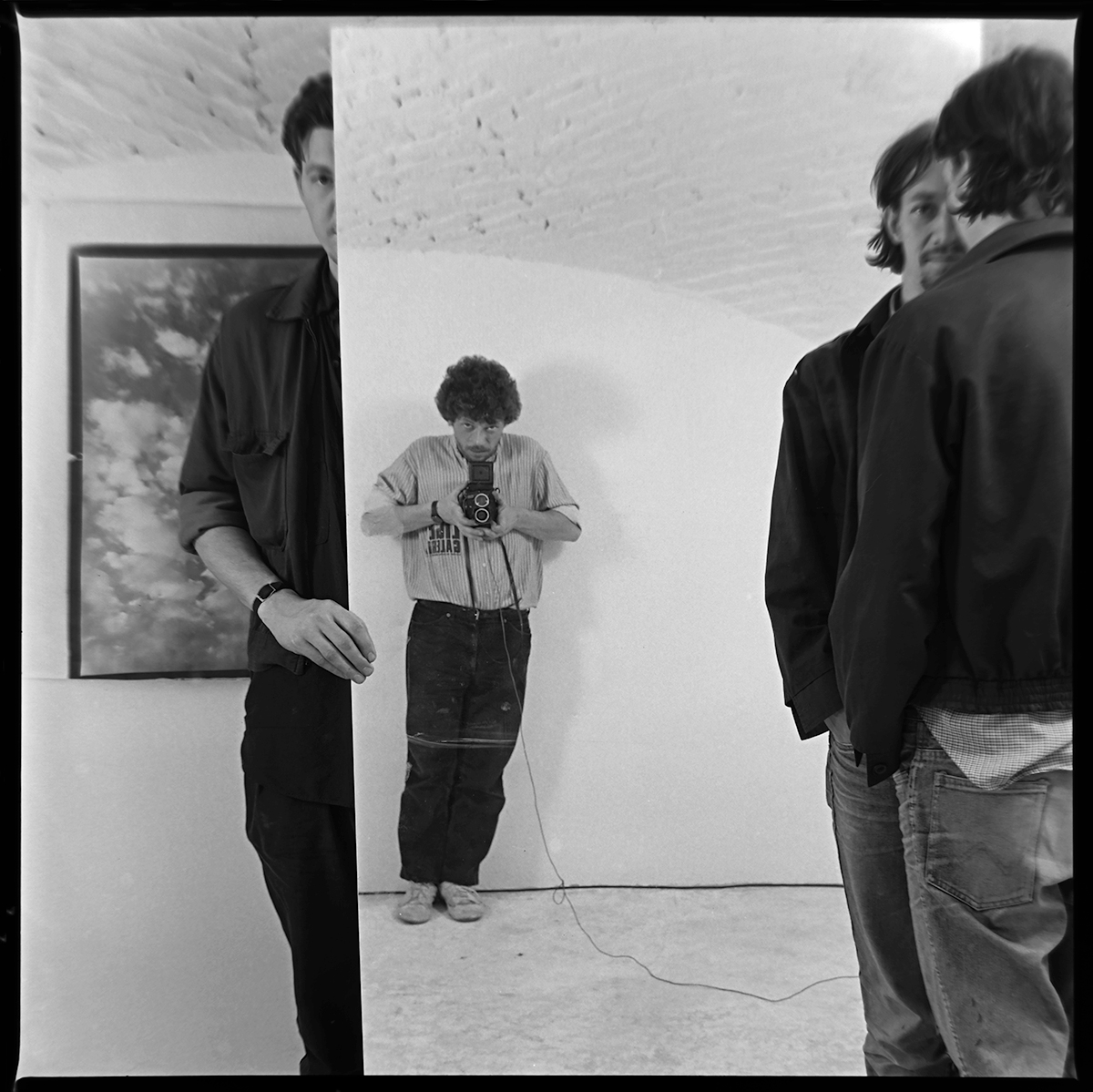

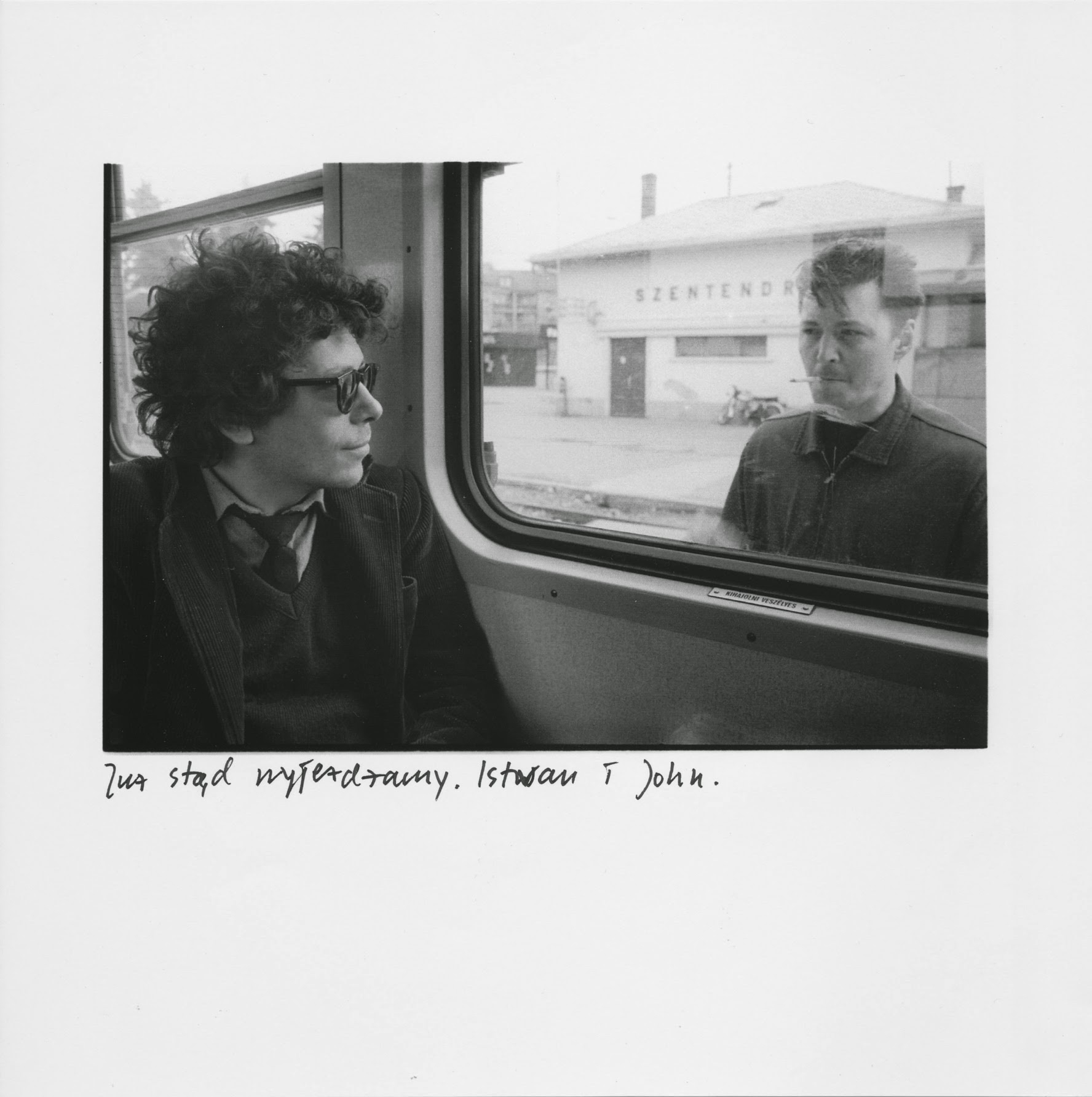

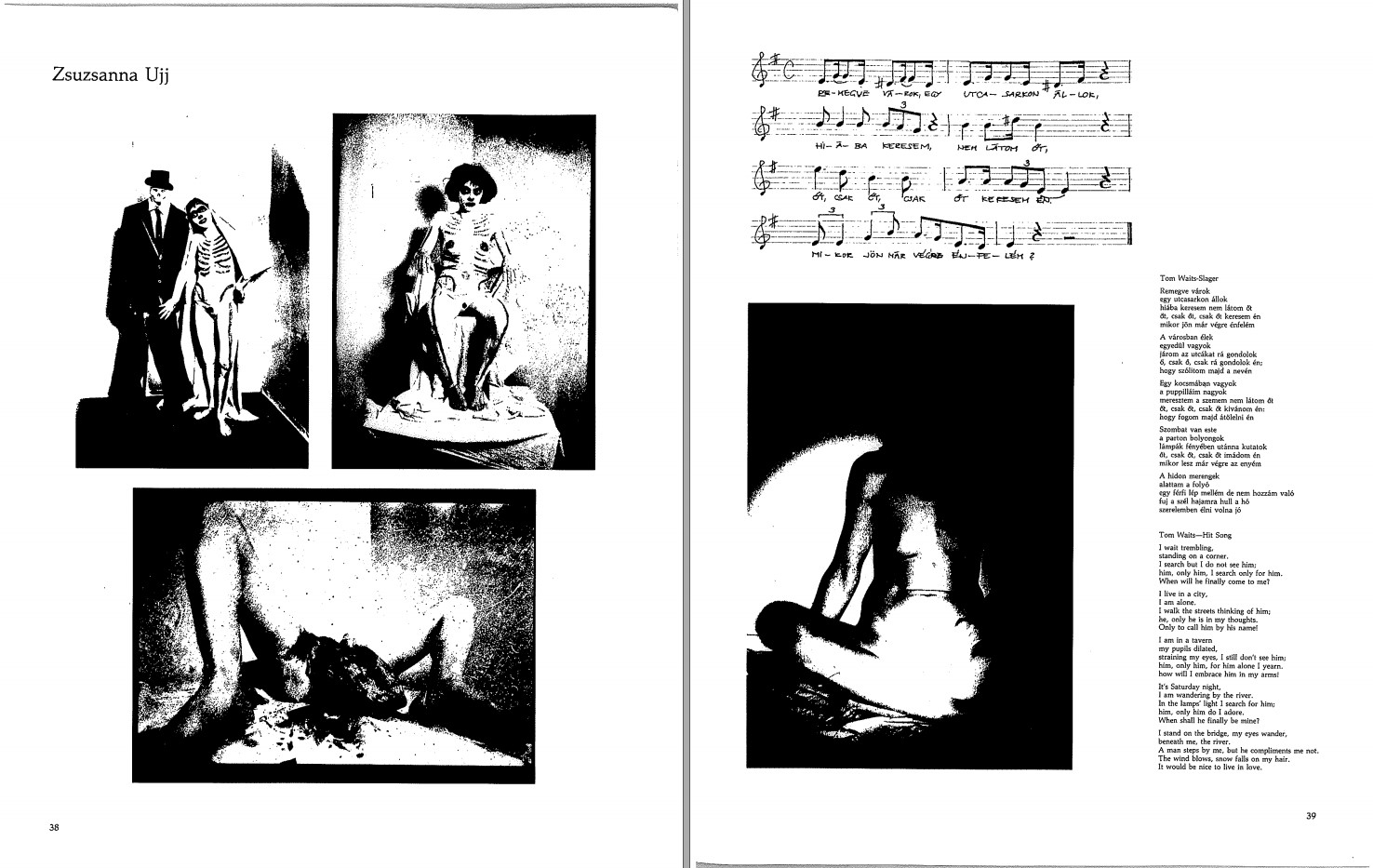

After returning to the US from his first visit to Eastern Europe, Jacob was invited by Dana Friis-Hansen, then a curator at the List Visual Arts Center at MIT, to submit a proposal to guest-curate an exhibition there, based on the Second Portfolio. Remarkably, considering Jacob’s lack of experience, the proposal was approved. Altogether unexpectedly, for himself and the artists he met earlier that year, Jacob returned to Eastern Europe in October 1986, and traveled to the Soviet Union for the first time. In Budapest, Várnagy organized a parallel exhibition at the Liget Galeria of the Hungarian photographers under consideration, not all of whom were ultimately included in the MIT exhibition. Jacob met István Halas, who had been abroad during Jacob’s first visit. Zsuzsanna Ujj, in the meantime, had begun work on a series of staged photographs. Halas, Ujj, Várnagy, and Jacob formed a close and enduring bond at this time.

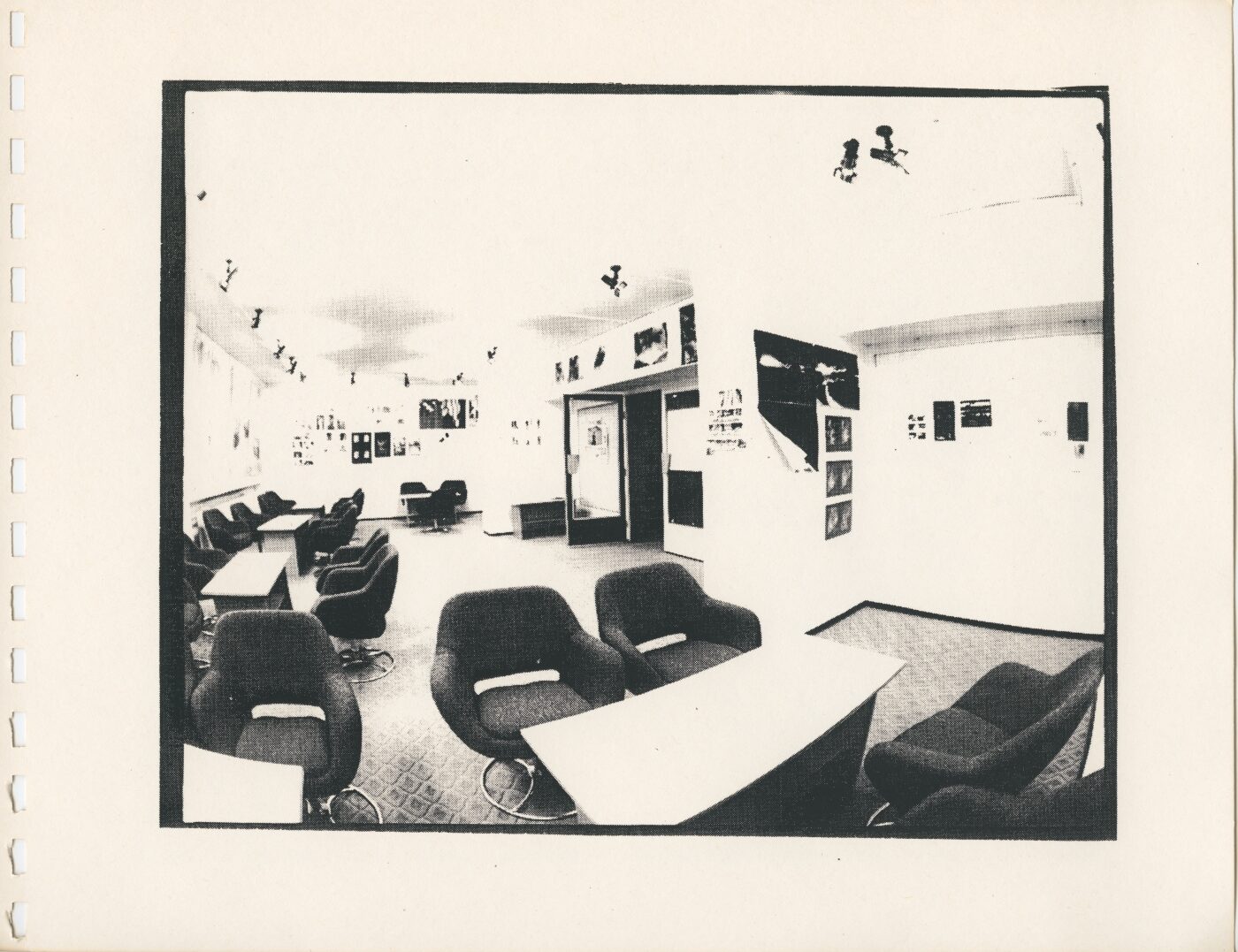

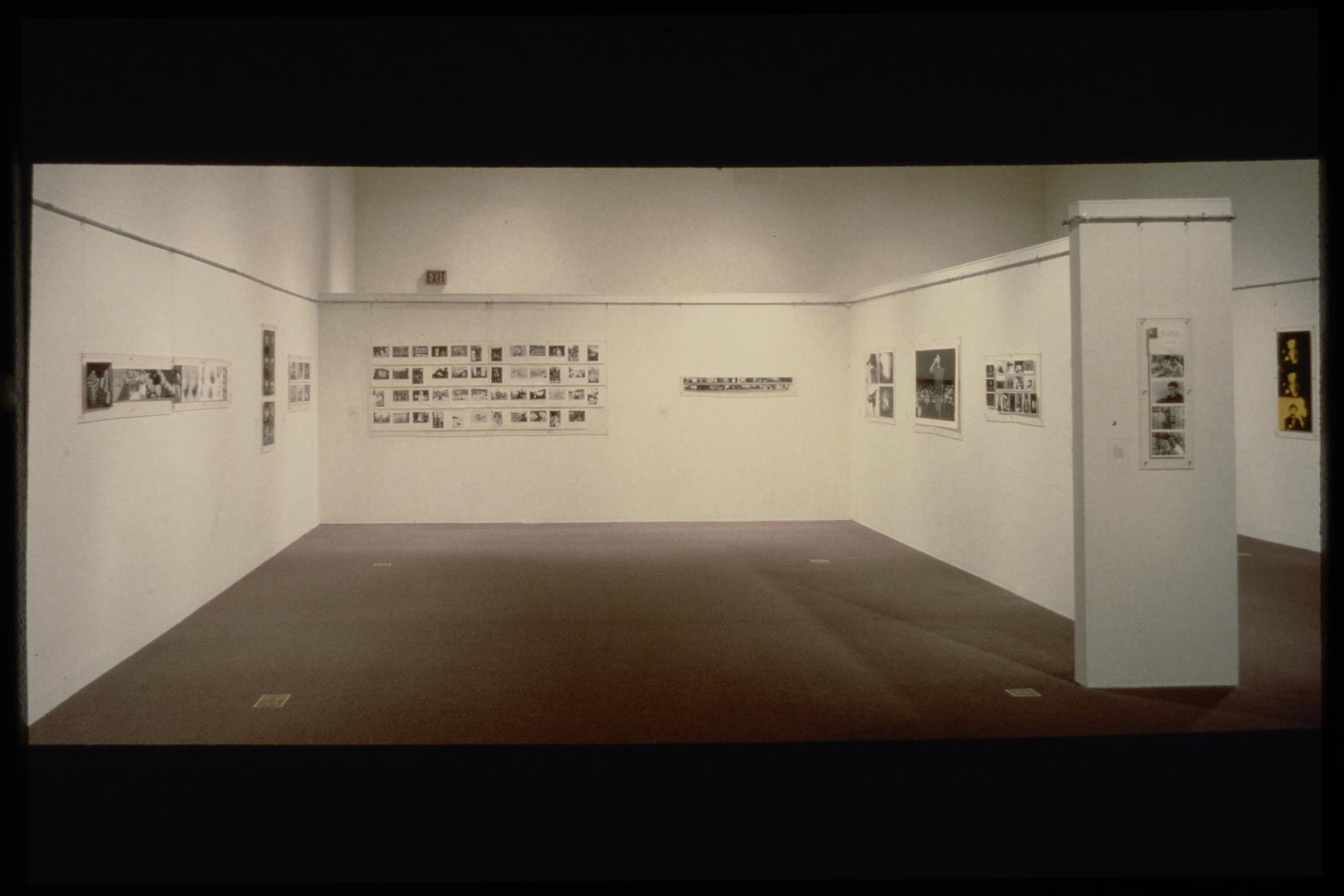

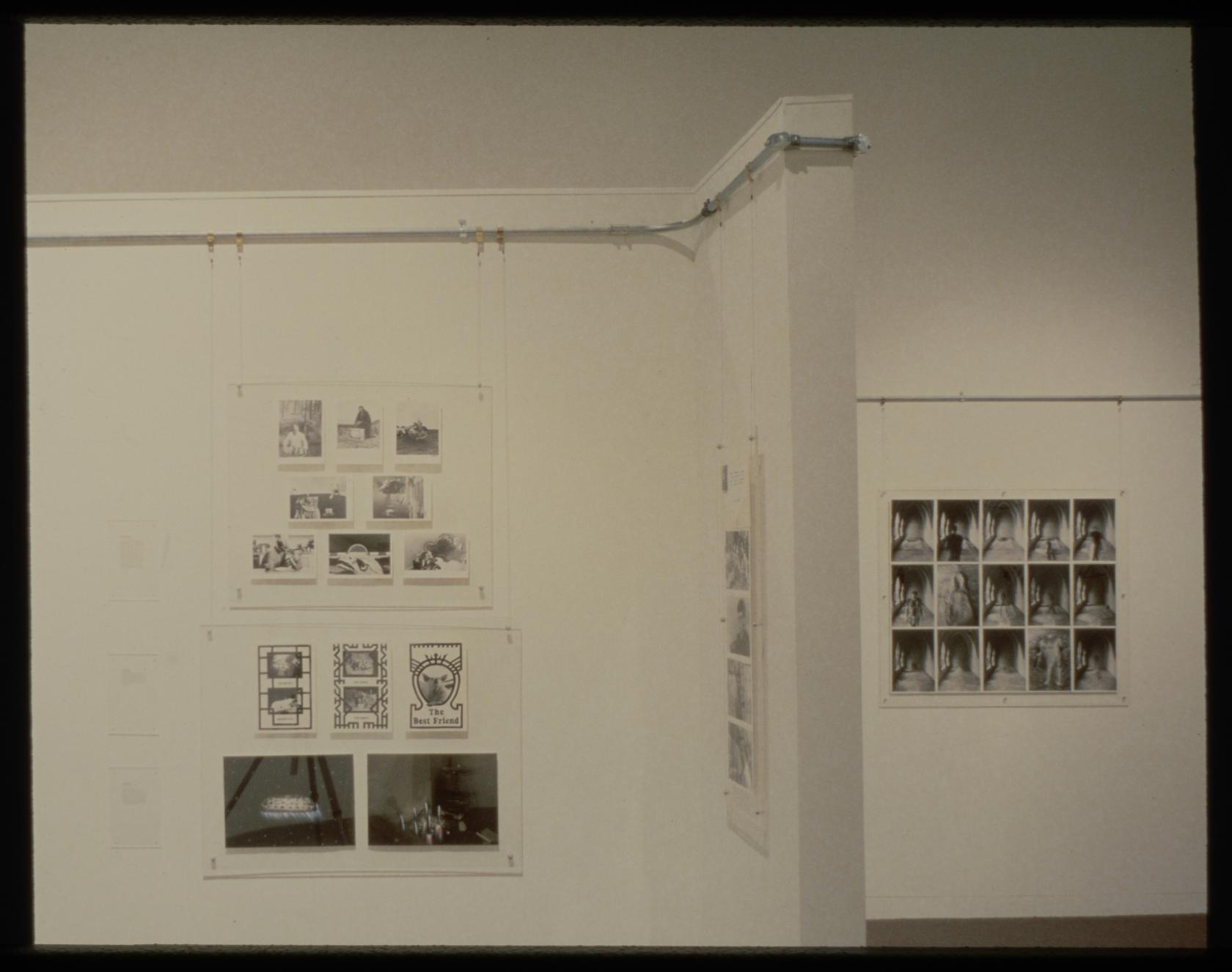

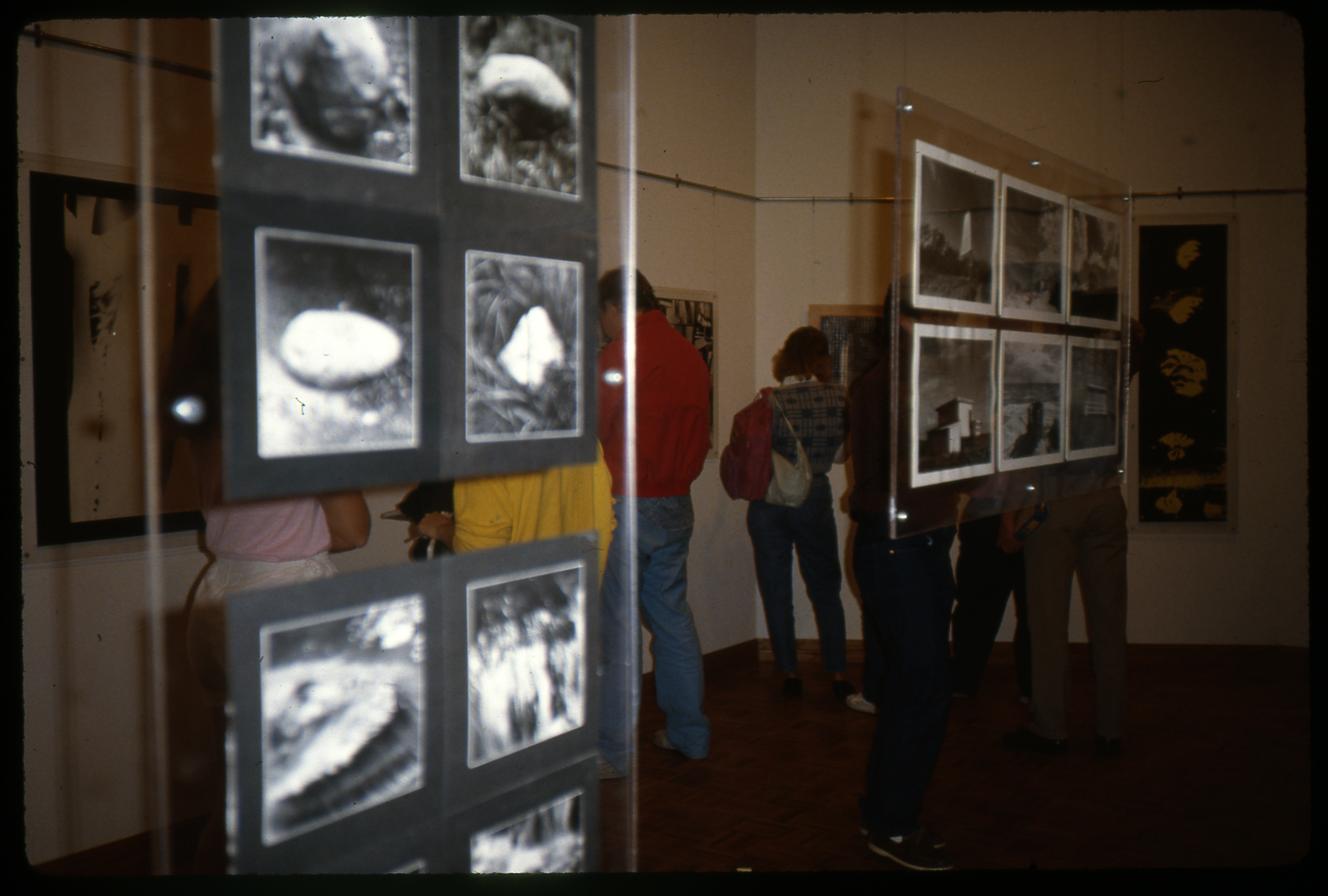

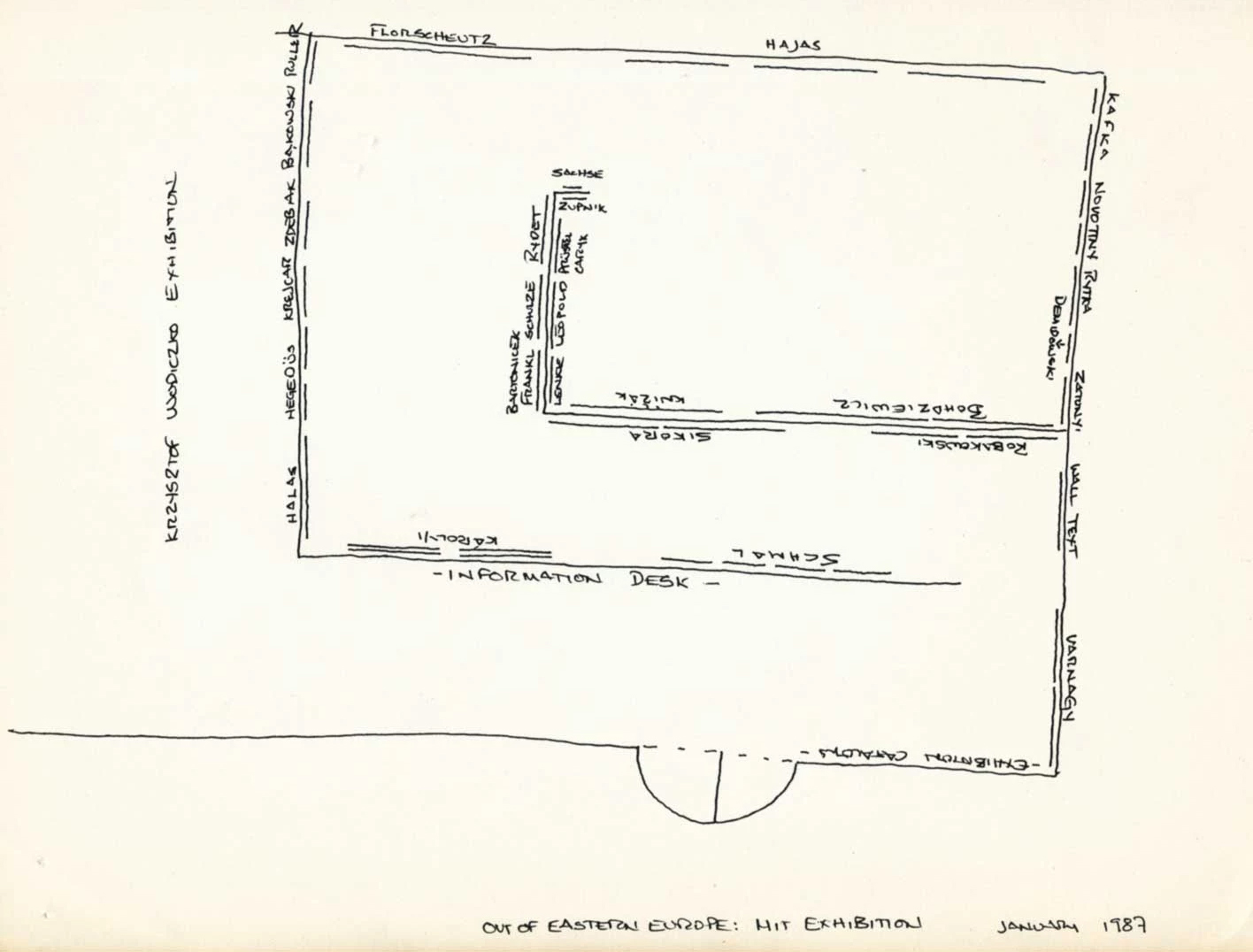

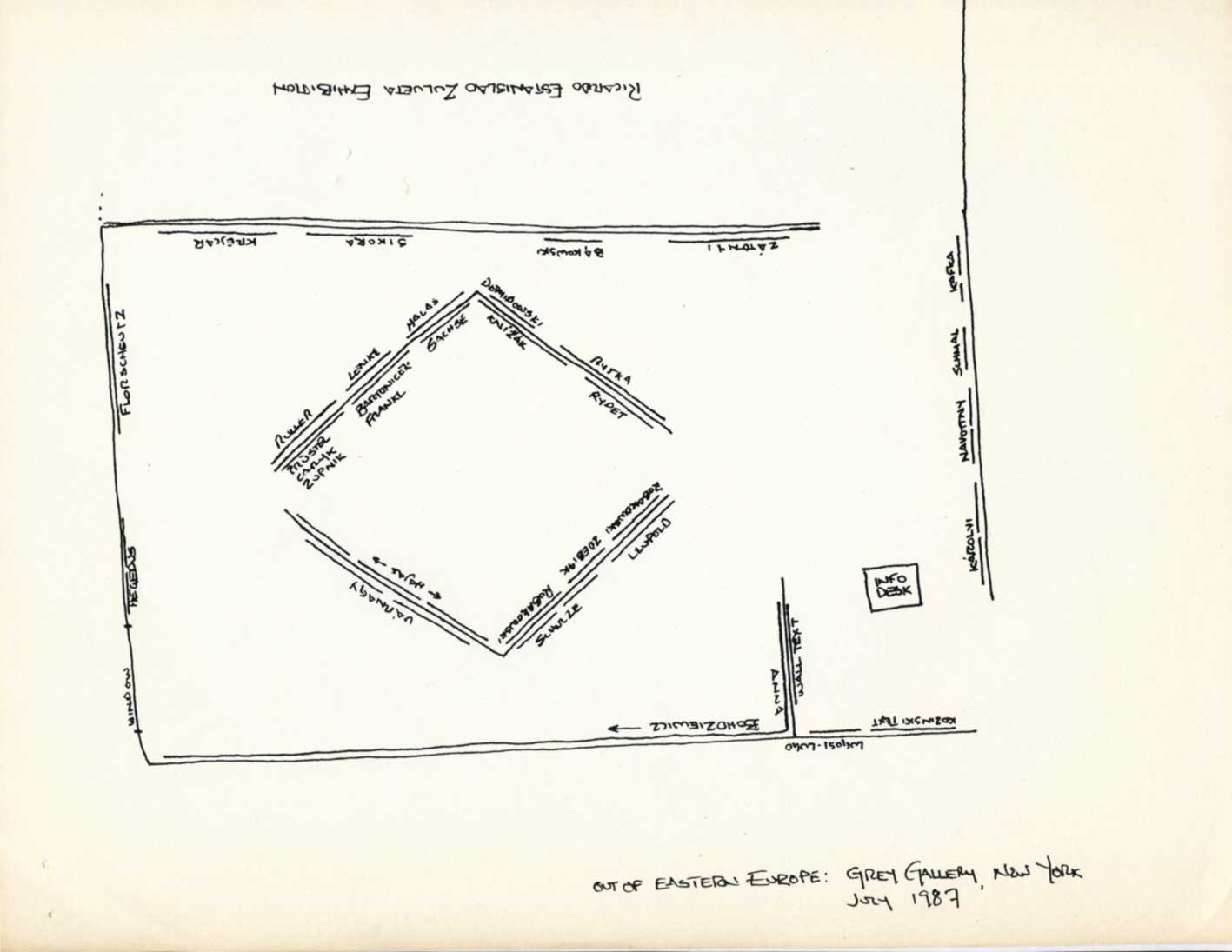

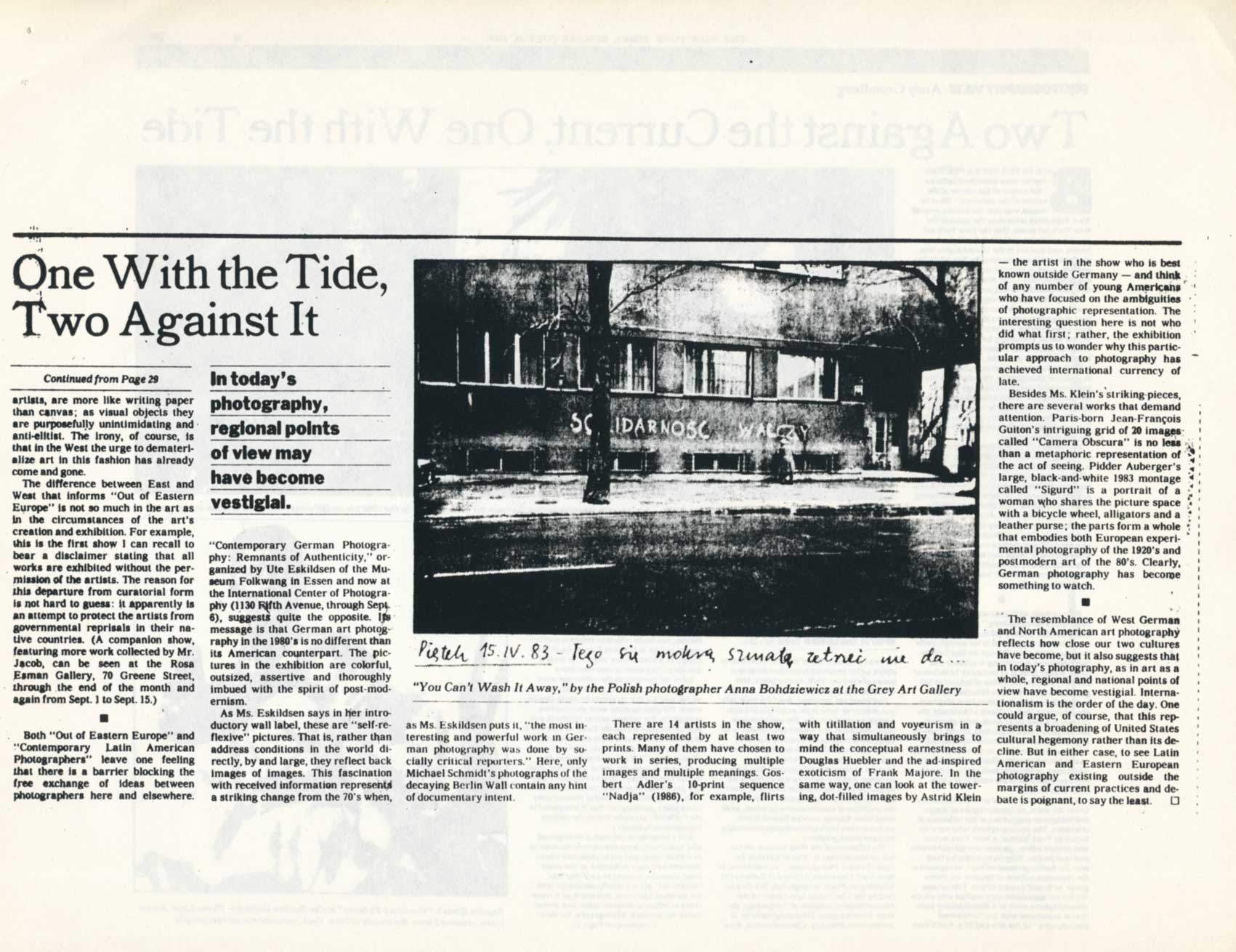

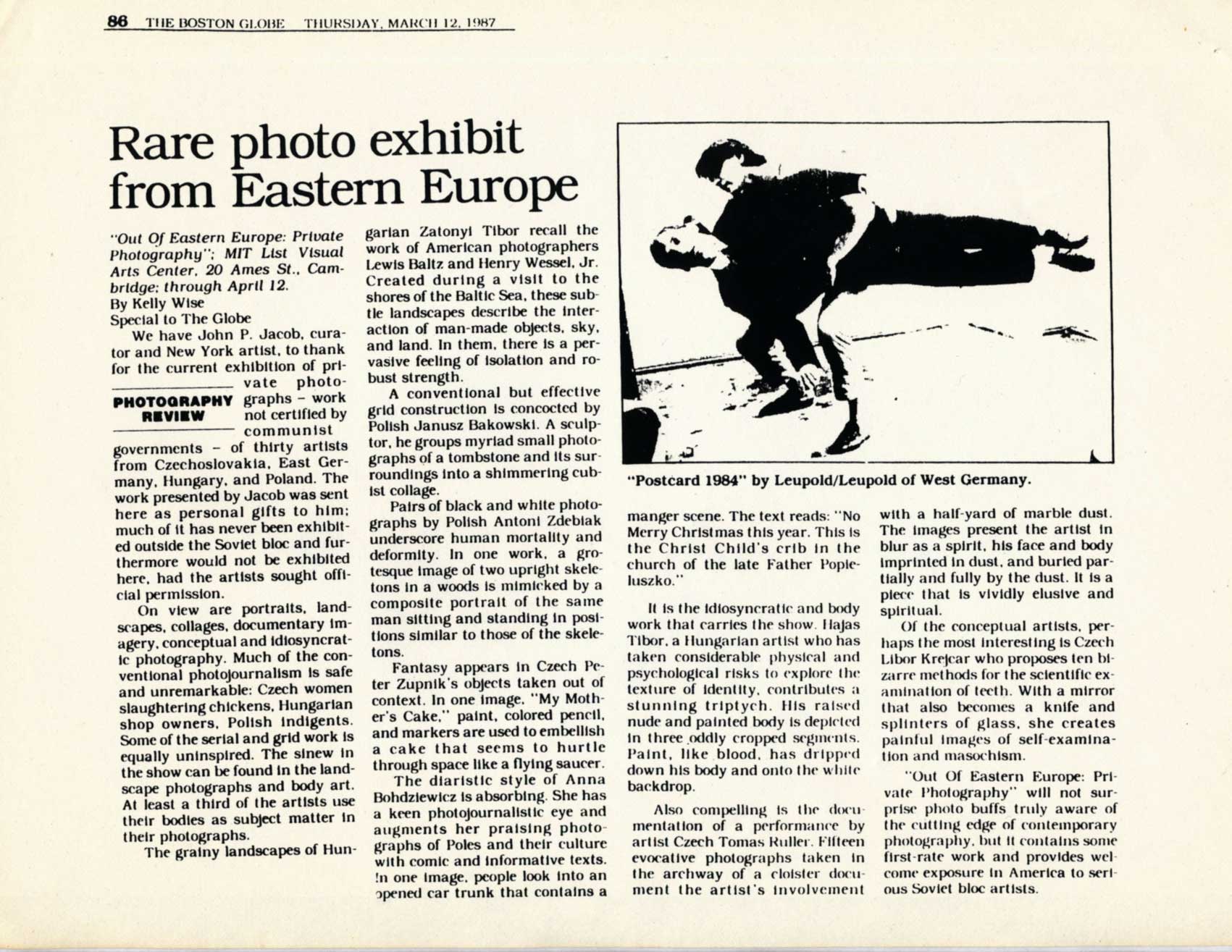

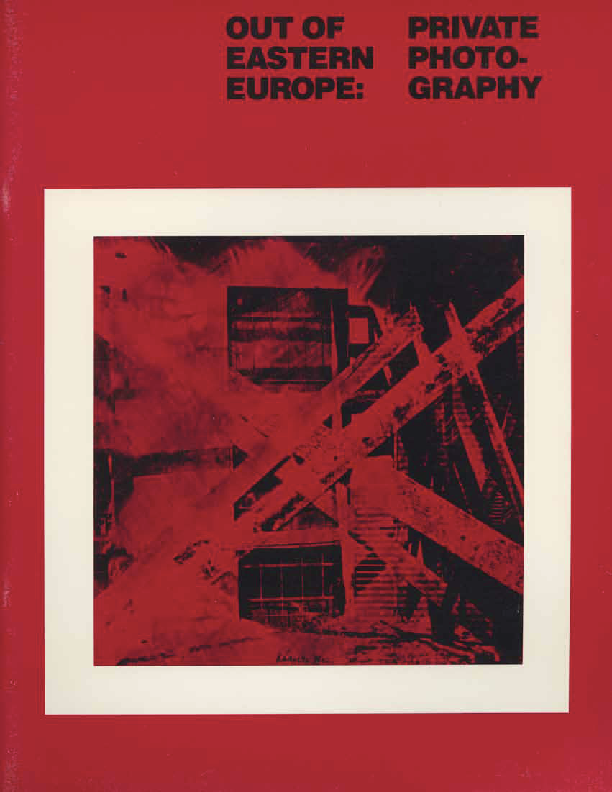

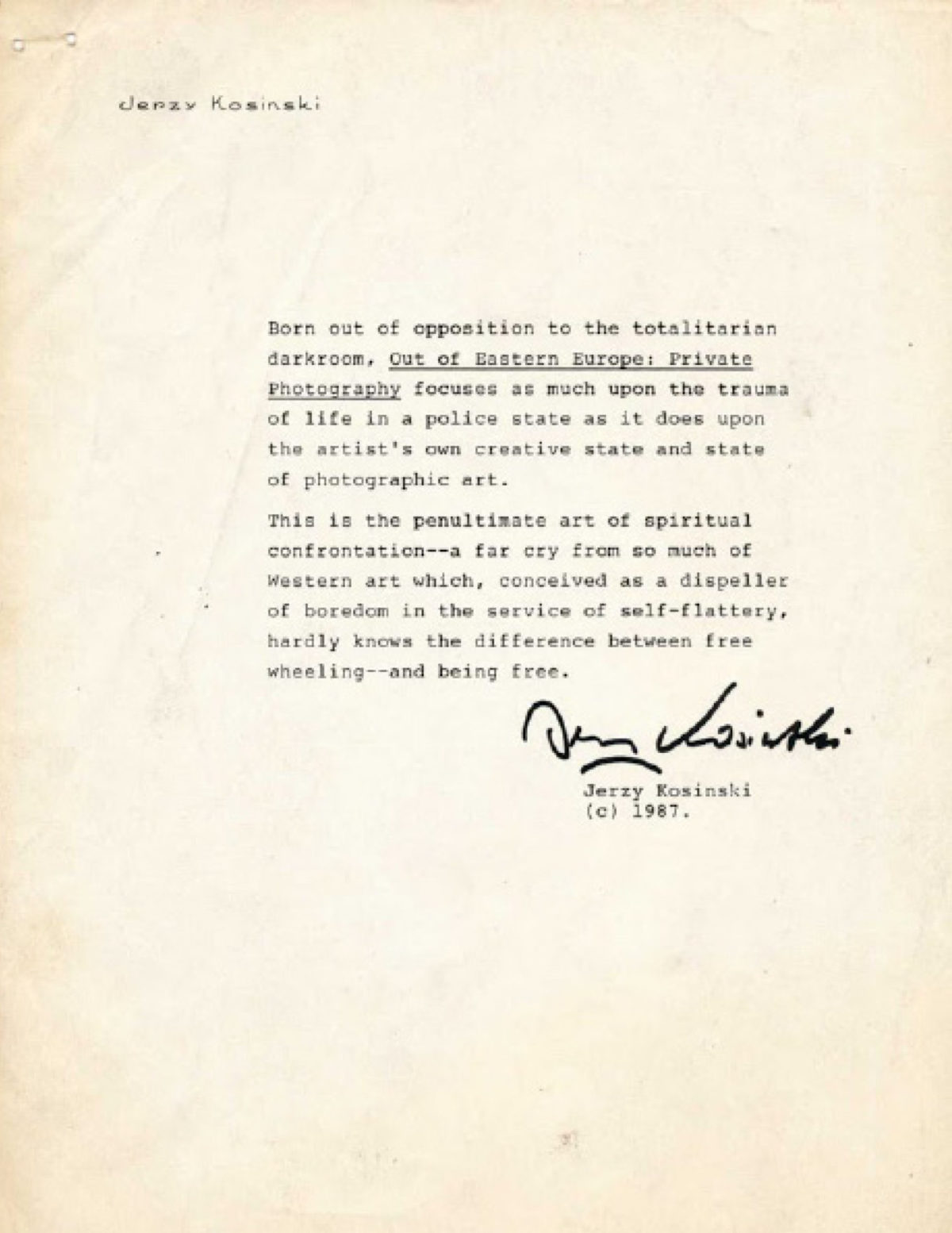

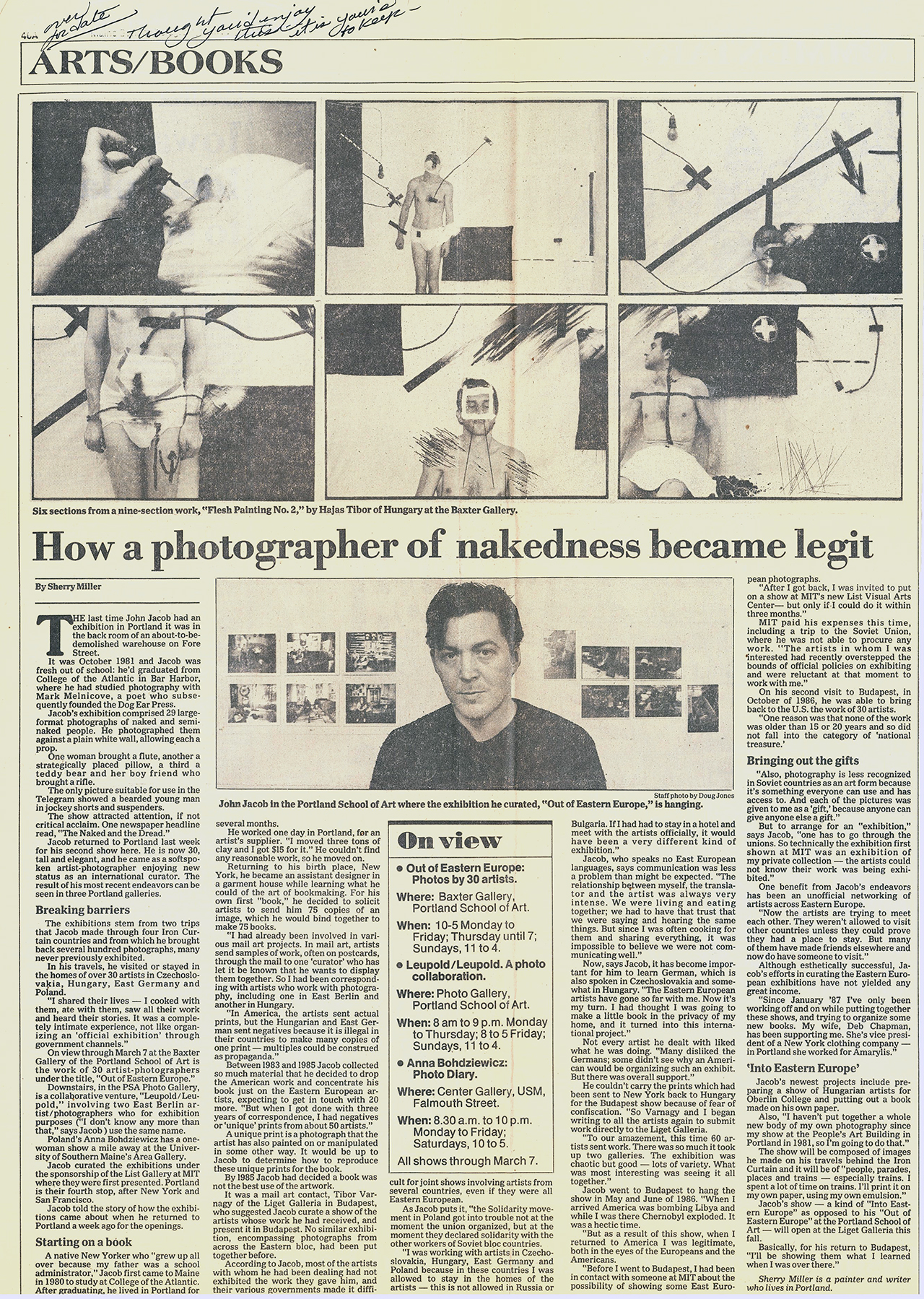

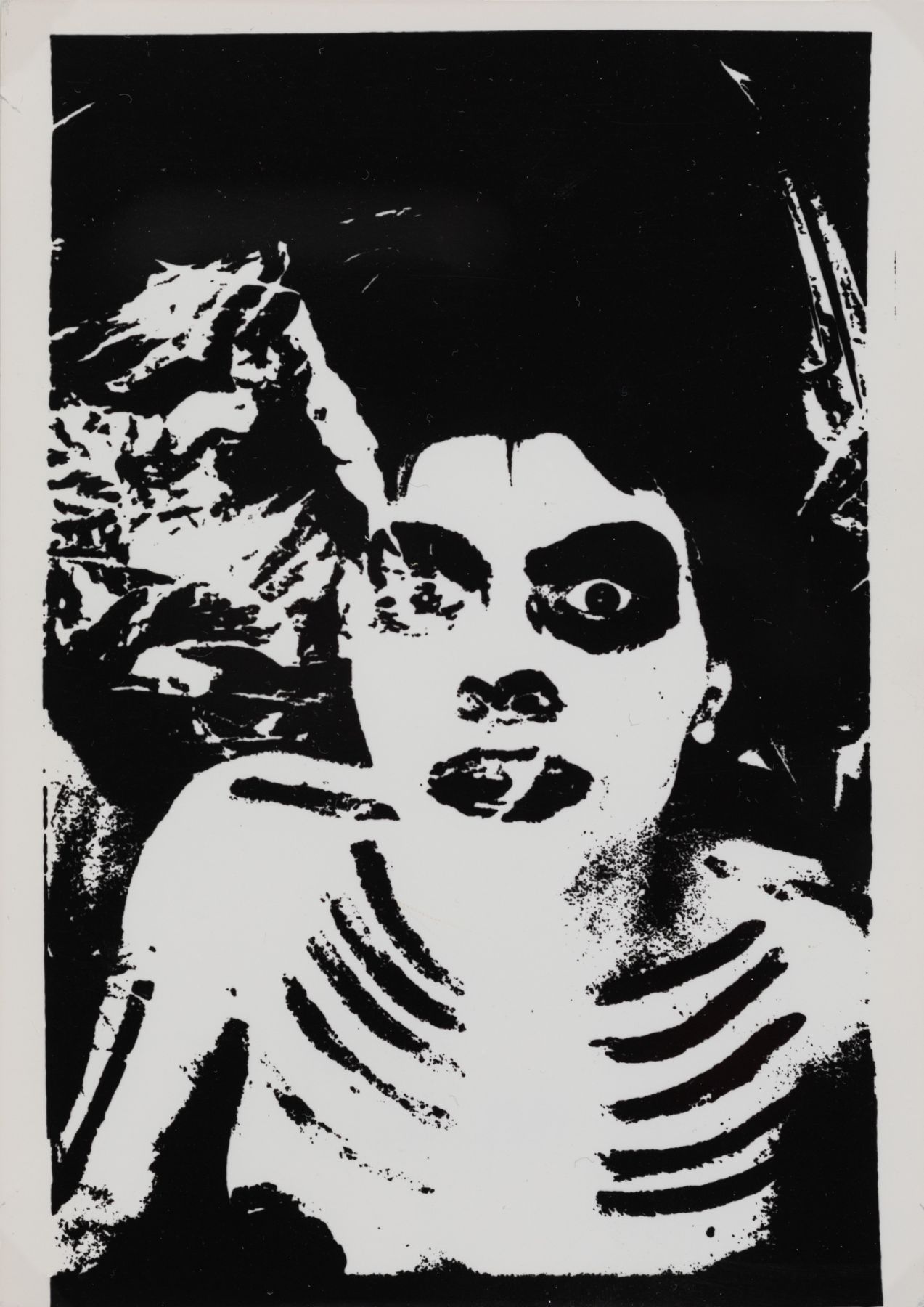

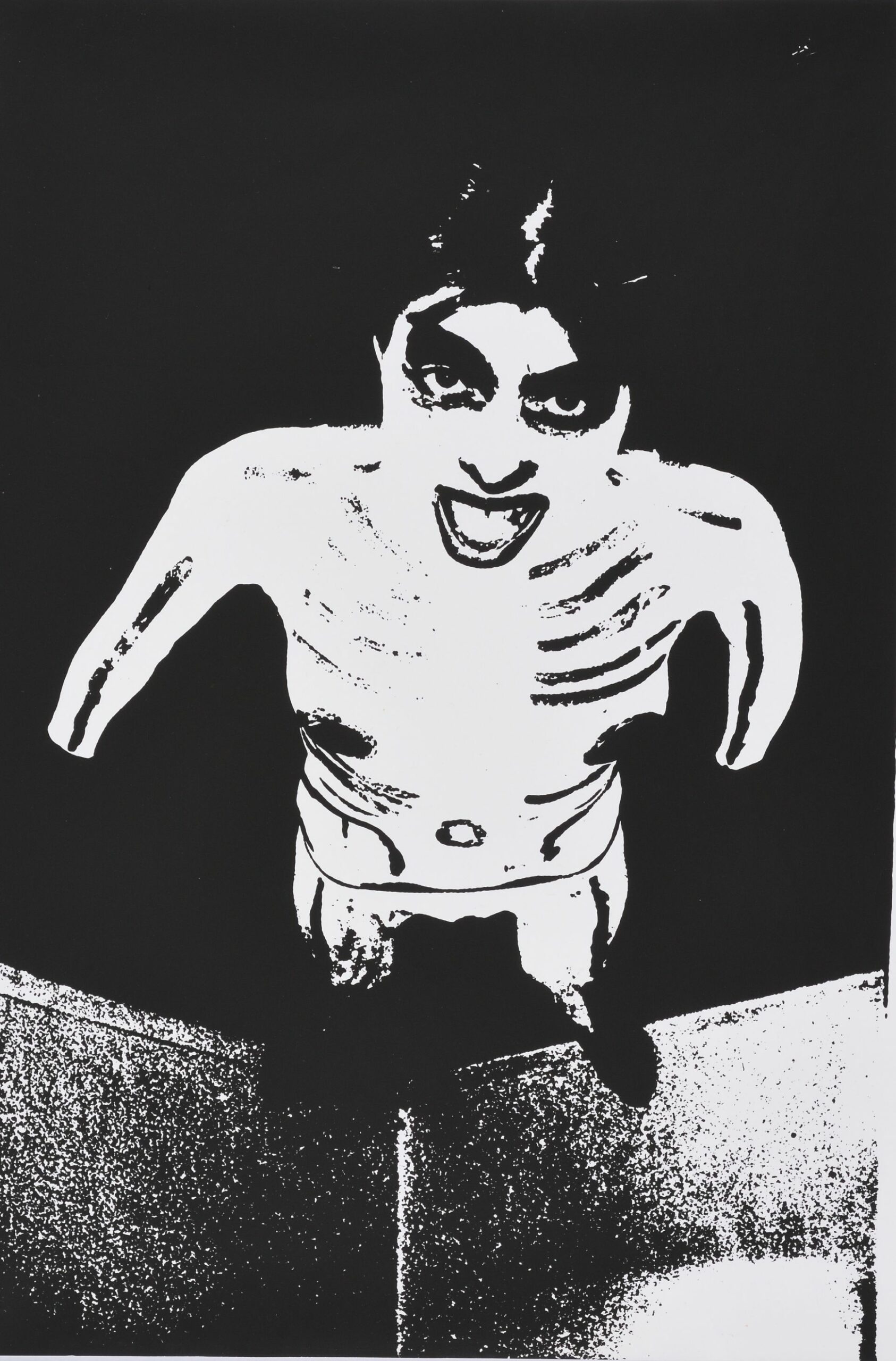

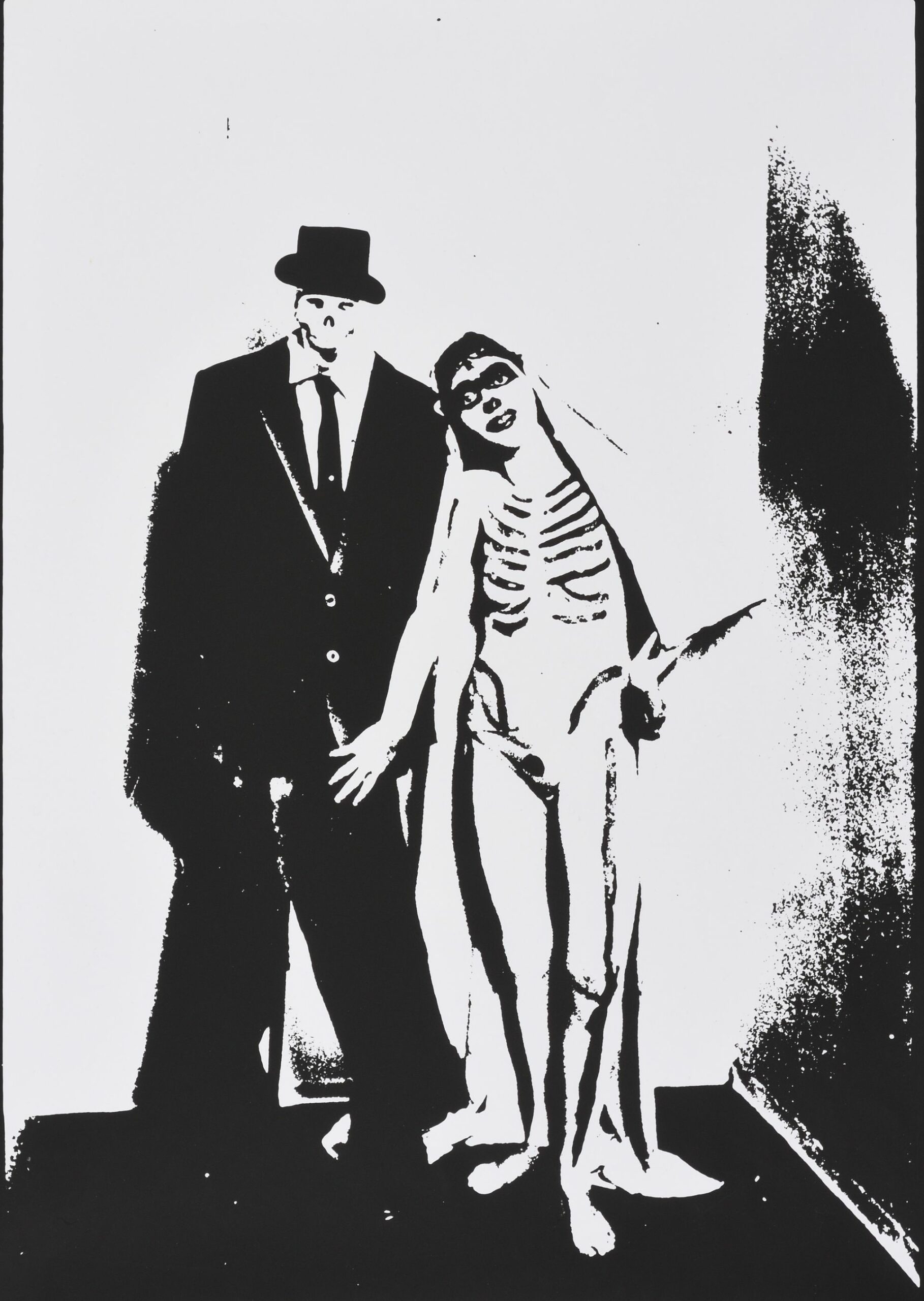

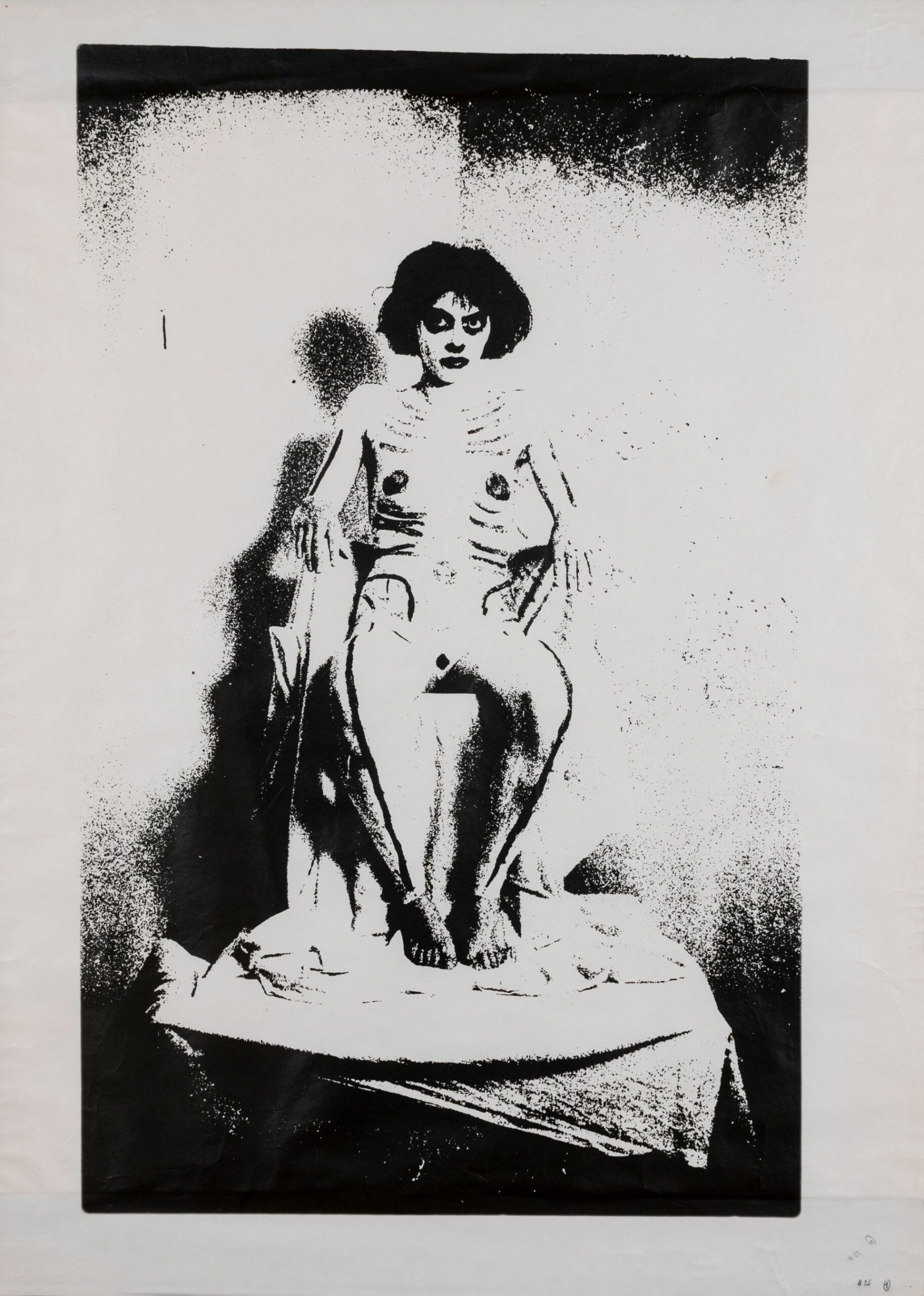

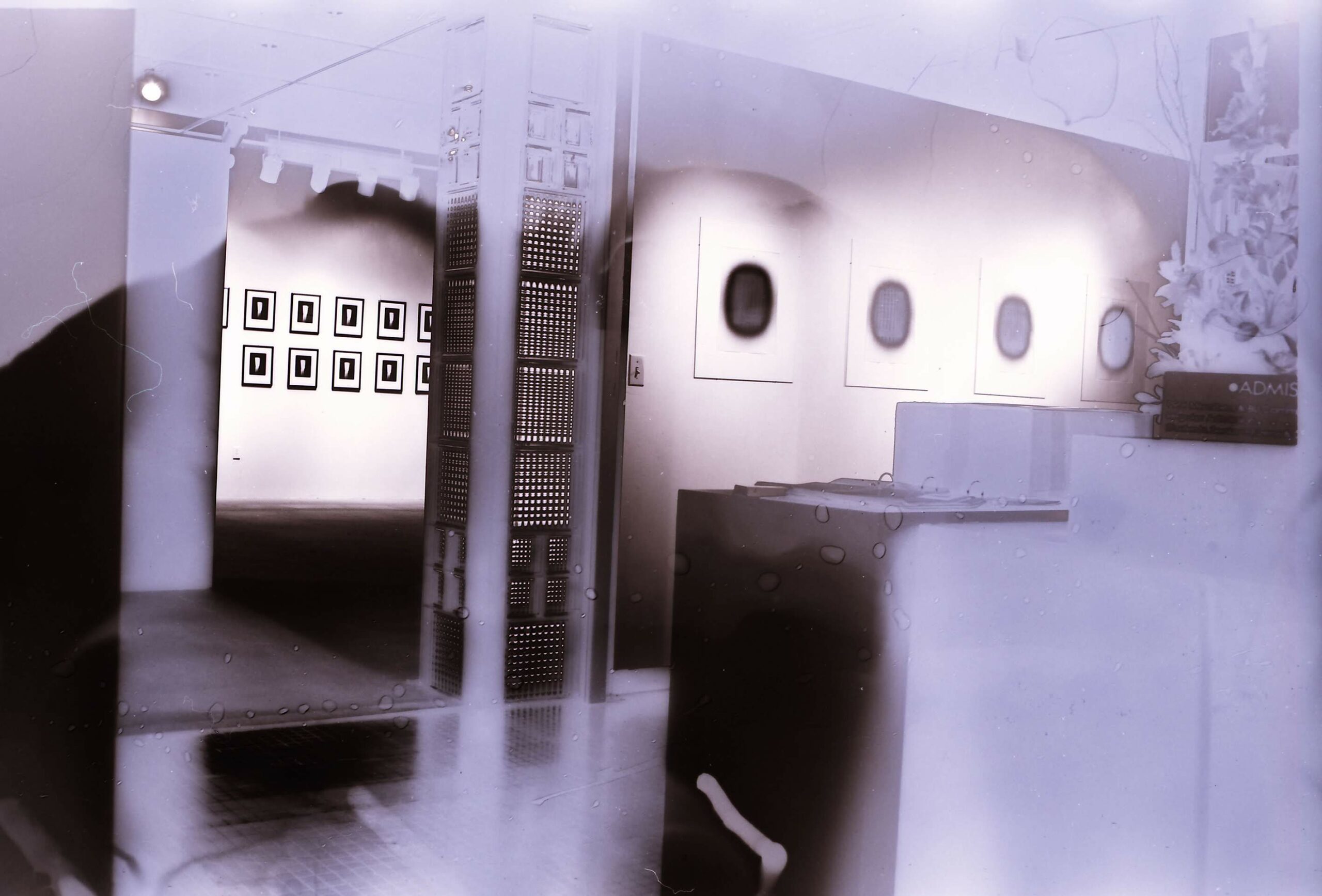

Out of Eastern Europe: Private Photography opened at the List Center in January, 1987. It was presented in conjunction with the exhibition Counter Monuments: Krzysztof Wodiczko’s Public Projections. Wodiczko, then living in New York, was an early advisor for the Second Portfolio project, and Jacob had introduced him to the List Center. A more concise selection than the Second Portfolio, Out of Eastern Europe focused on artists working in the Soviet Bloc nations Jacob had visited. The exhibition included works by thirty artists from Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, and Poland, and was accompanied by a catalog with essays by Jacob and Lynn Zelevansky. Repeating the security measure used in Budapest, the catalog included a disclaimer that the works presented were from Jacob’s personal collection, and were exhibited without permission of the artists. For its presentation in New York City, at the Grey Art Gallery at New York University, then directed by Tom Sokolowski, émigré writer Jerzy Kosinski contributed an introductory statement describing the exhibition as “the penultimate art of spiritual confrontation.”

In retrospect, Out of Eastern Europe was a transitional event for Jacob. All earlier exhibitions, including the presentation of the Second Portfolio in Budapest, had been guided by the mail art principles “No fee, no jury, all works shown, none returned.” All earlier printed works, particularly the multi-volume International Portfolio project, were guided by the principle of assembling. In his text for the First Portfolio, Jacob declared that principle “perhaps the most important advancement in the curatorial arts during this century,” because it denied the curator her traditional authority and placed it in the hands of artists. Though he wore his authority lightly and with visible discomfort in Out of Eastern Europe, it was a curated exhibition. It was a first, with real consequences for Jacob.

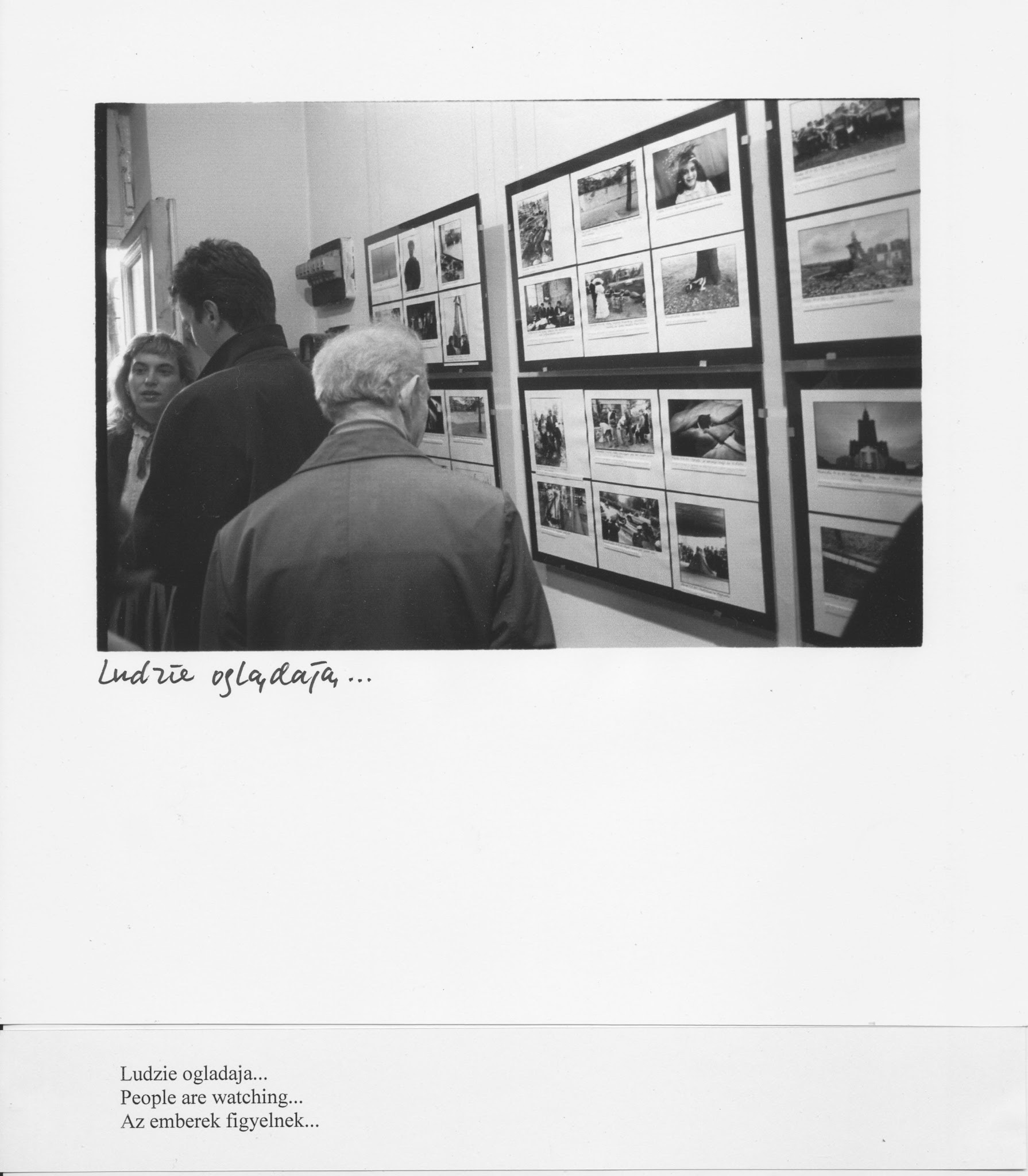

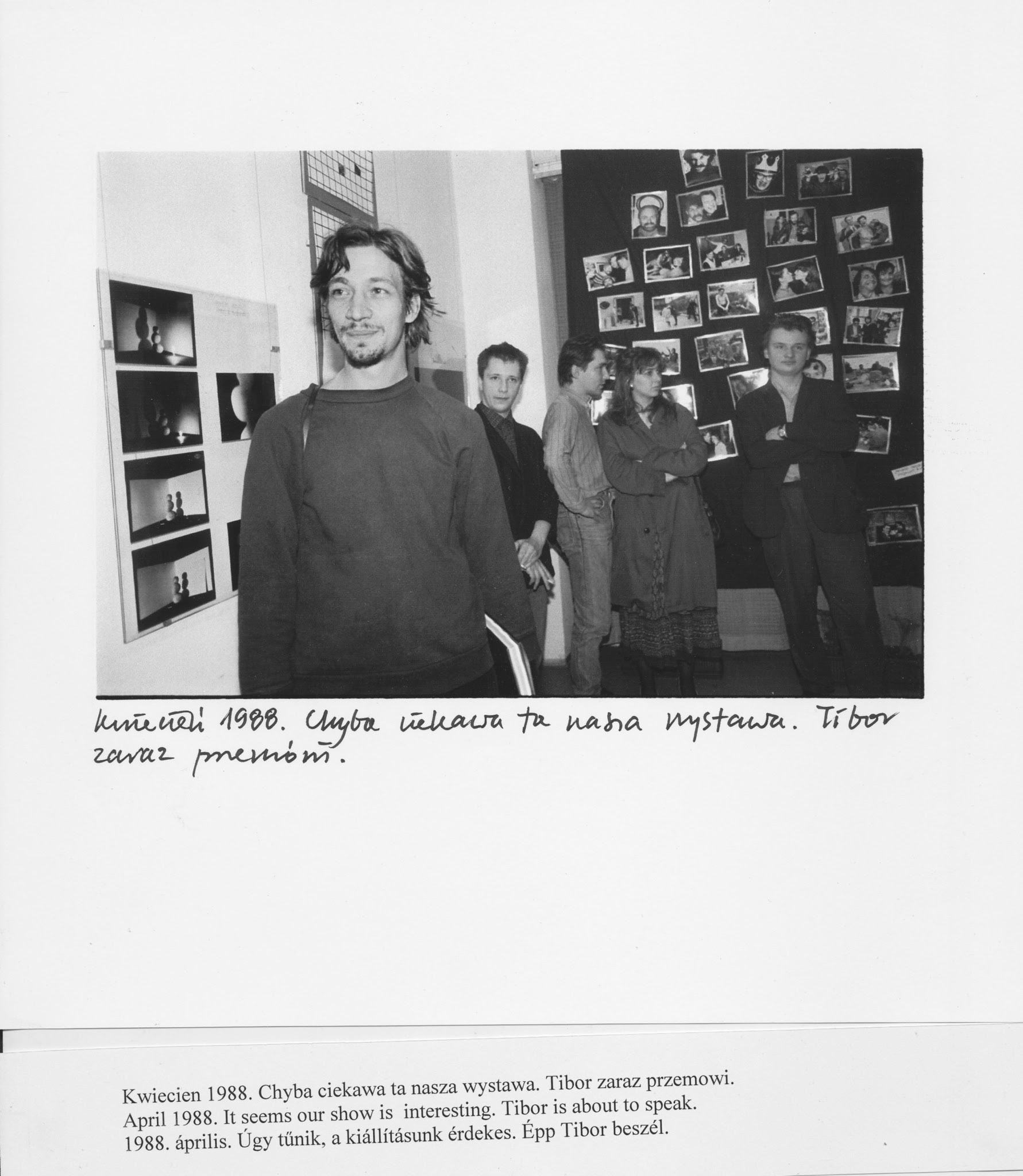

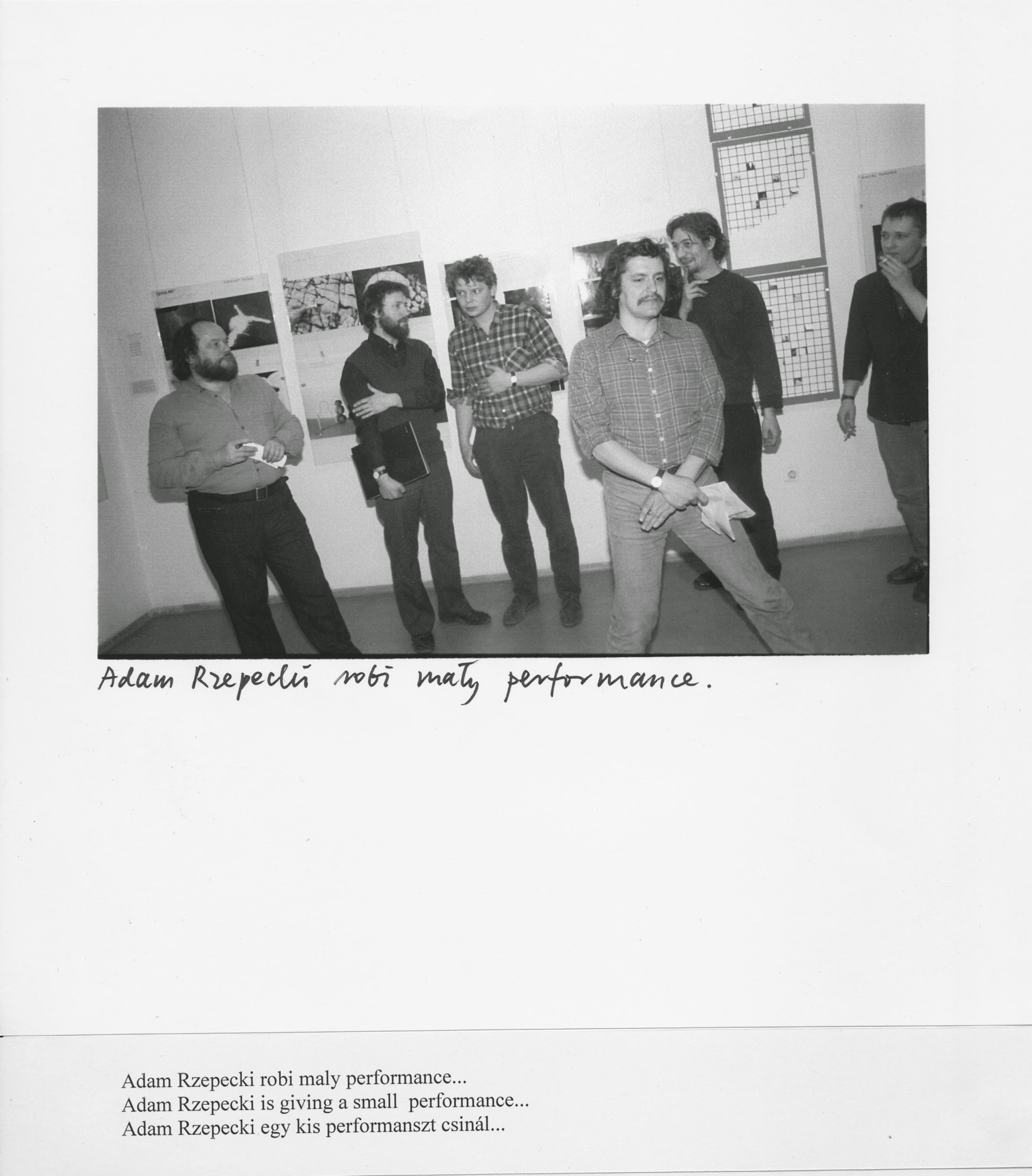

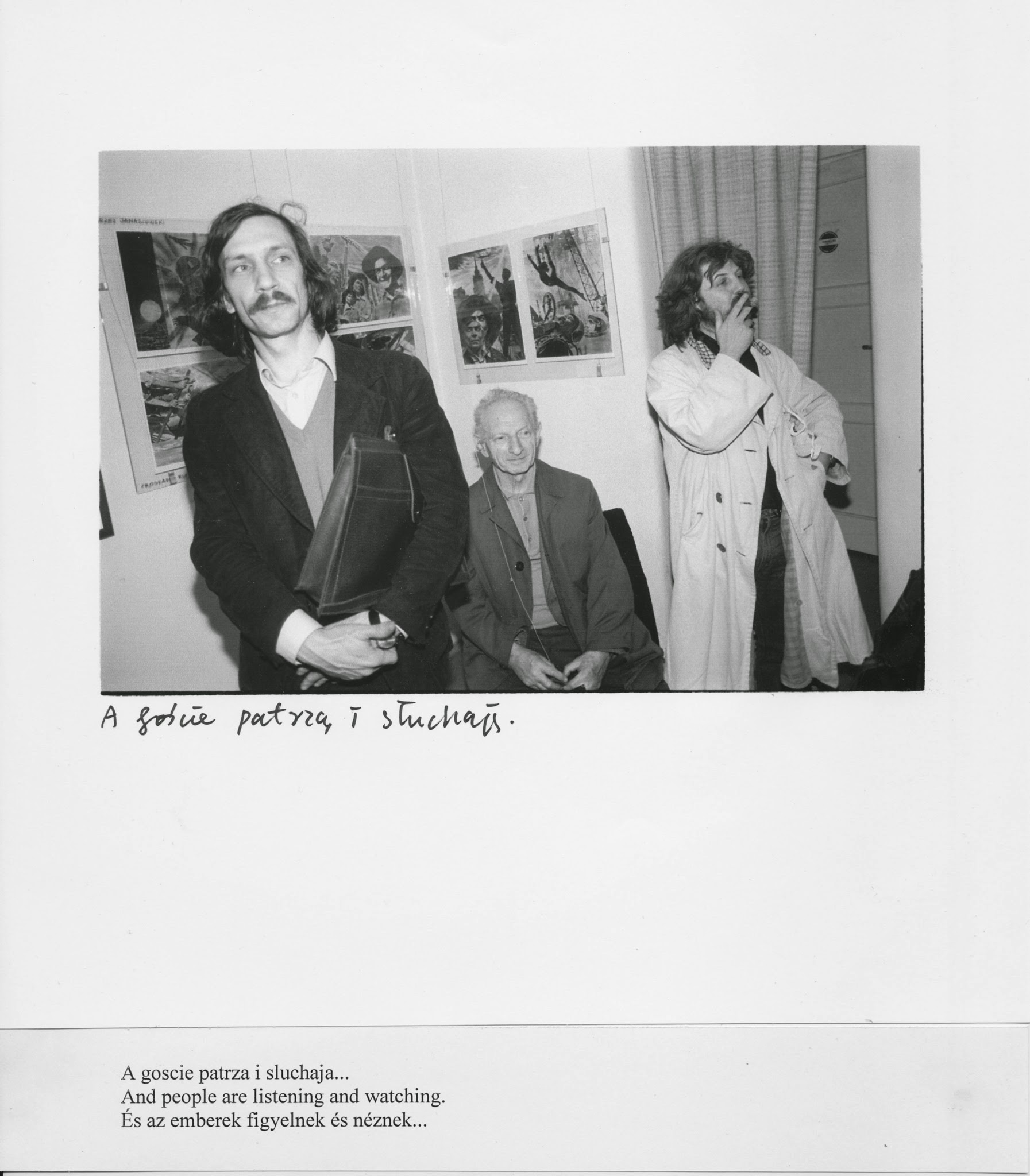

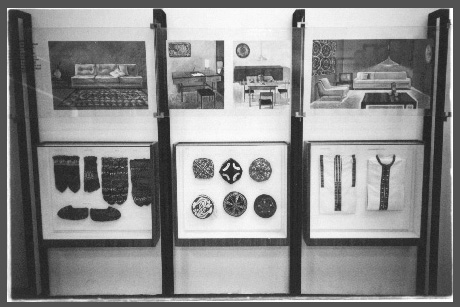

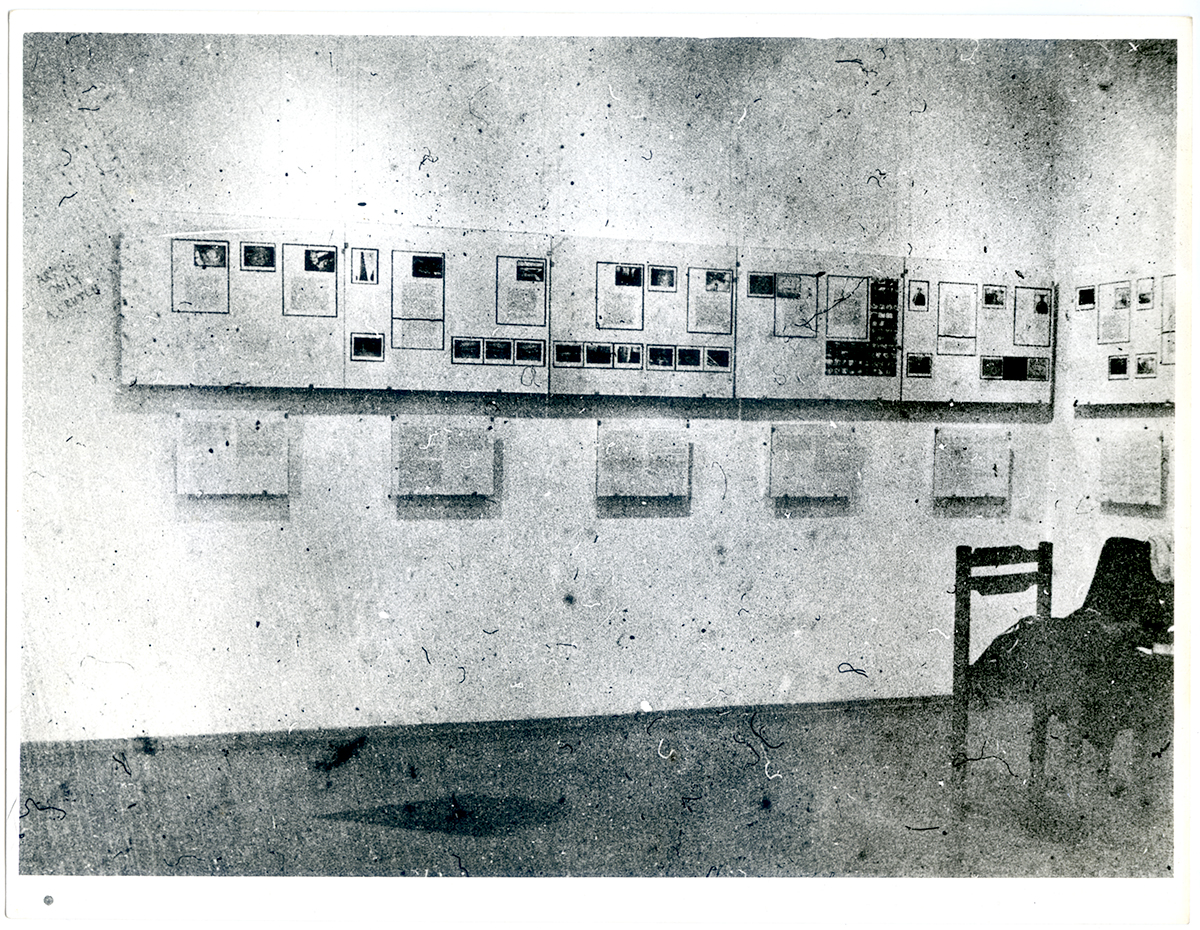

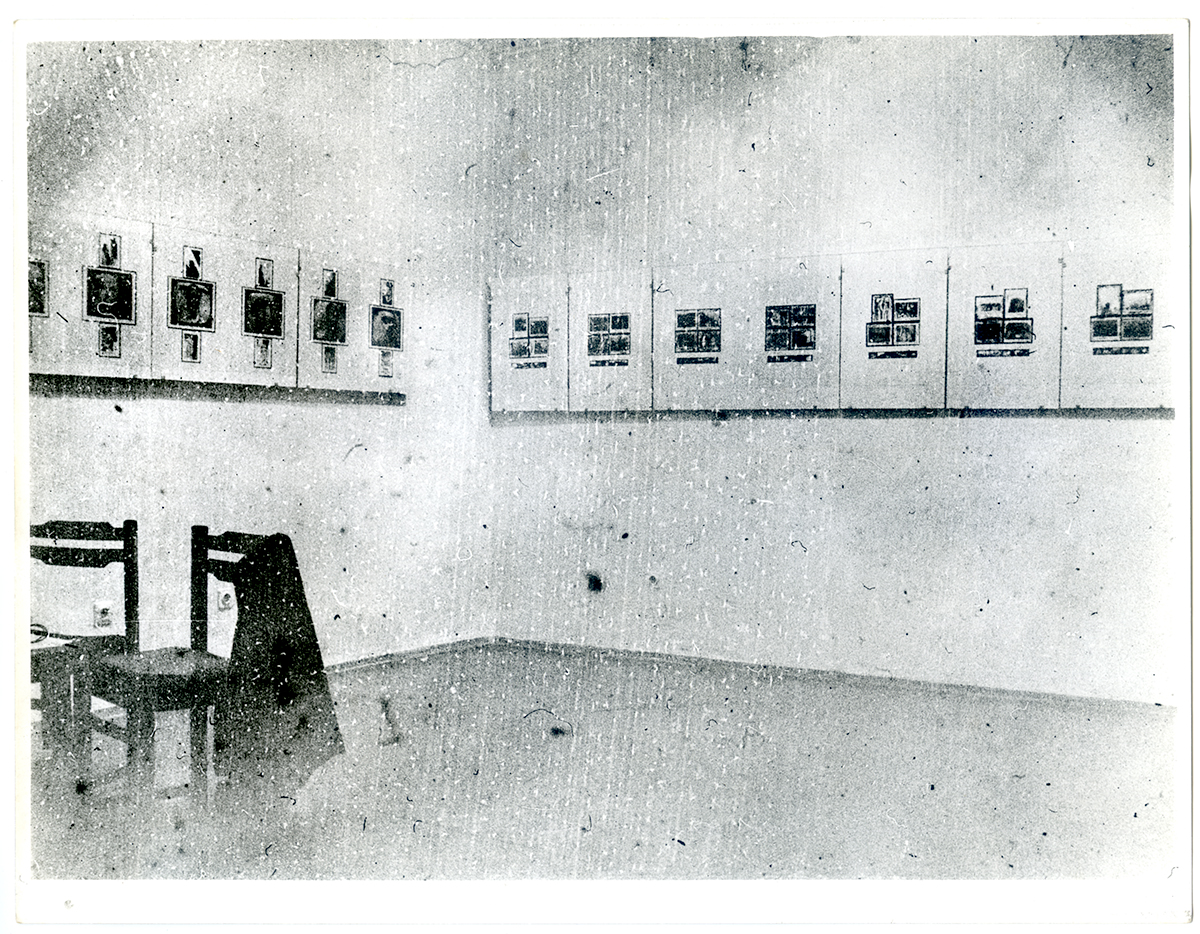

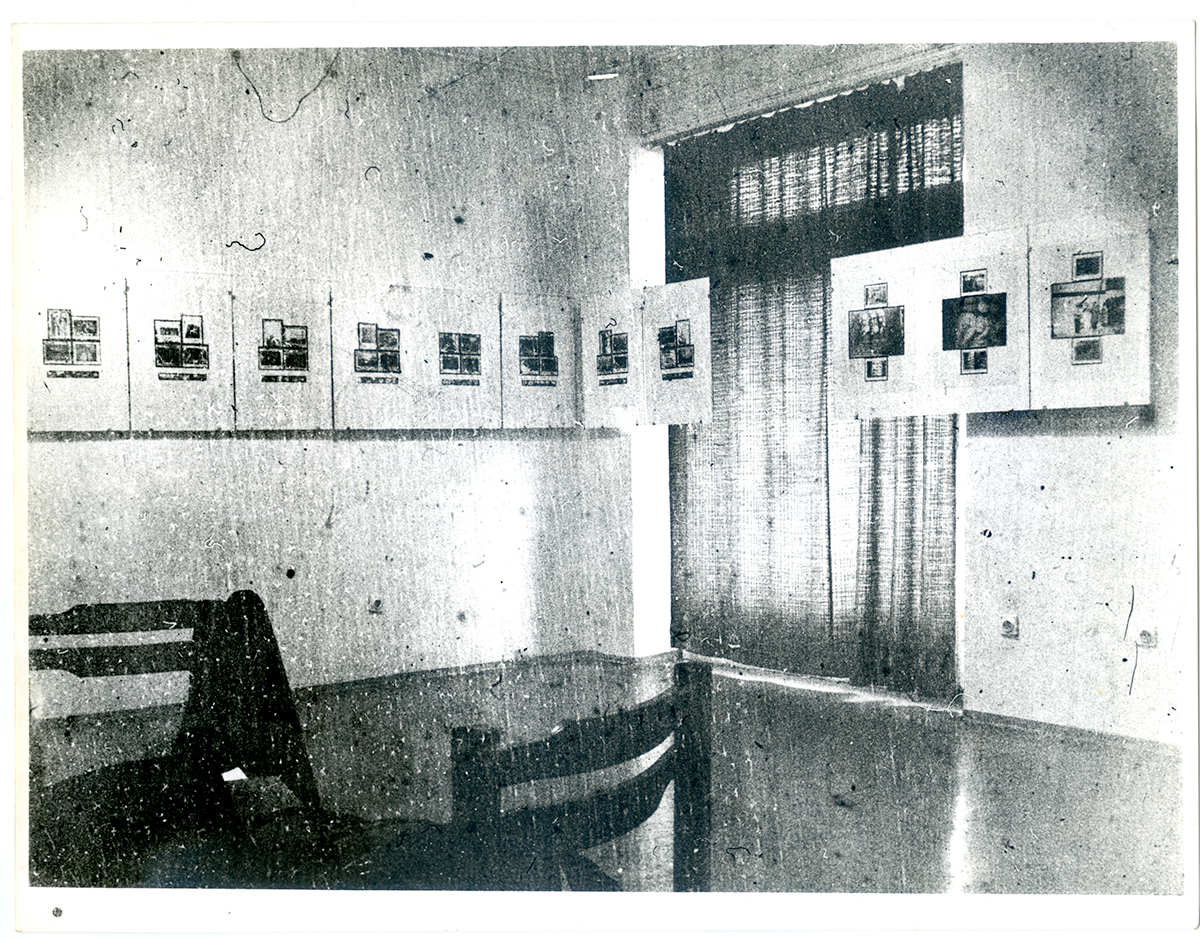

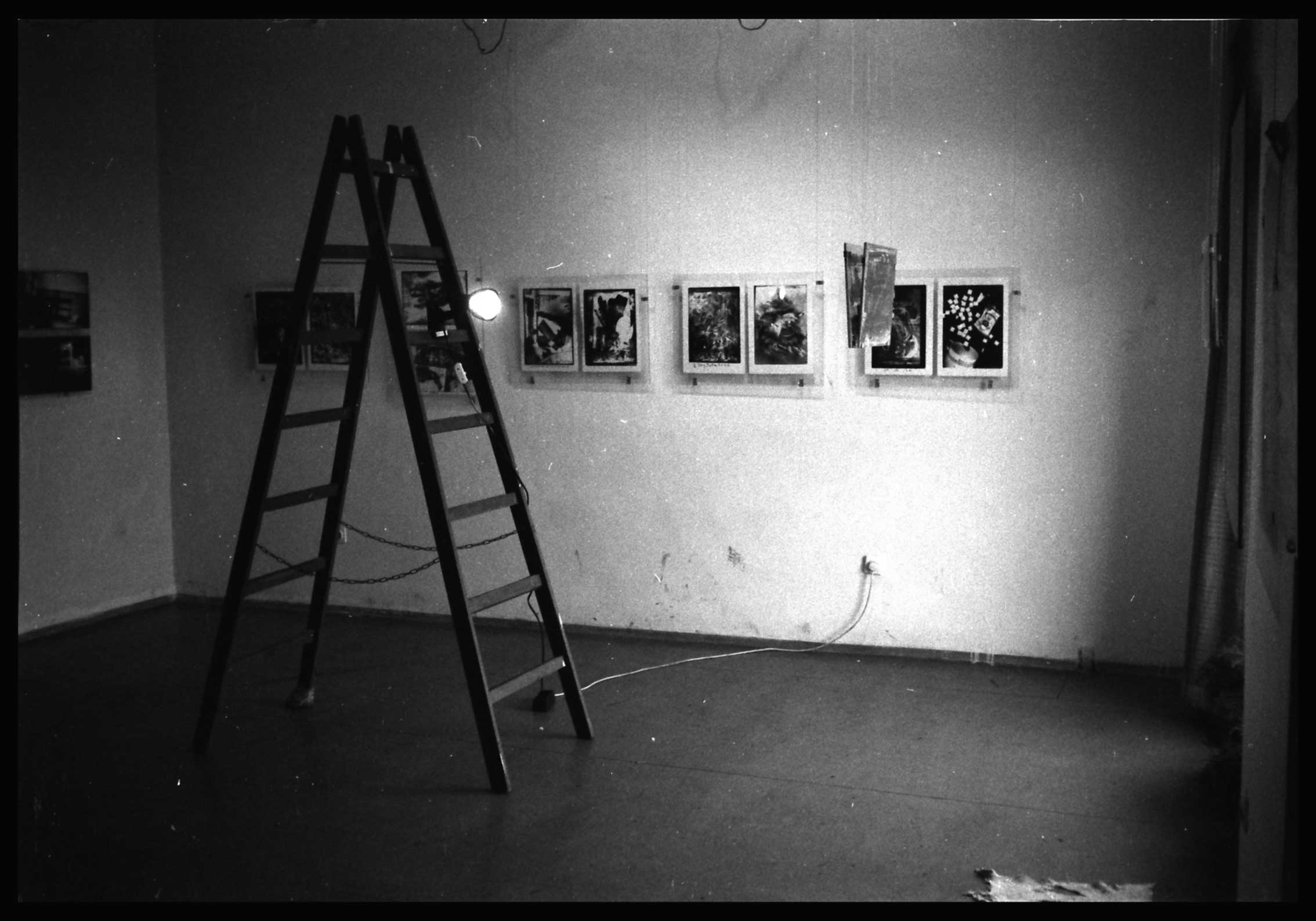

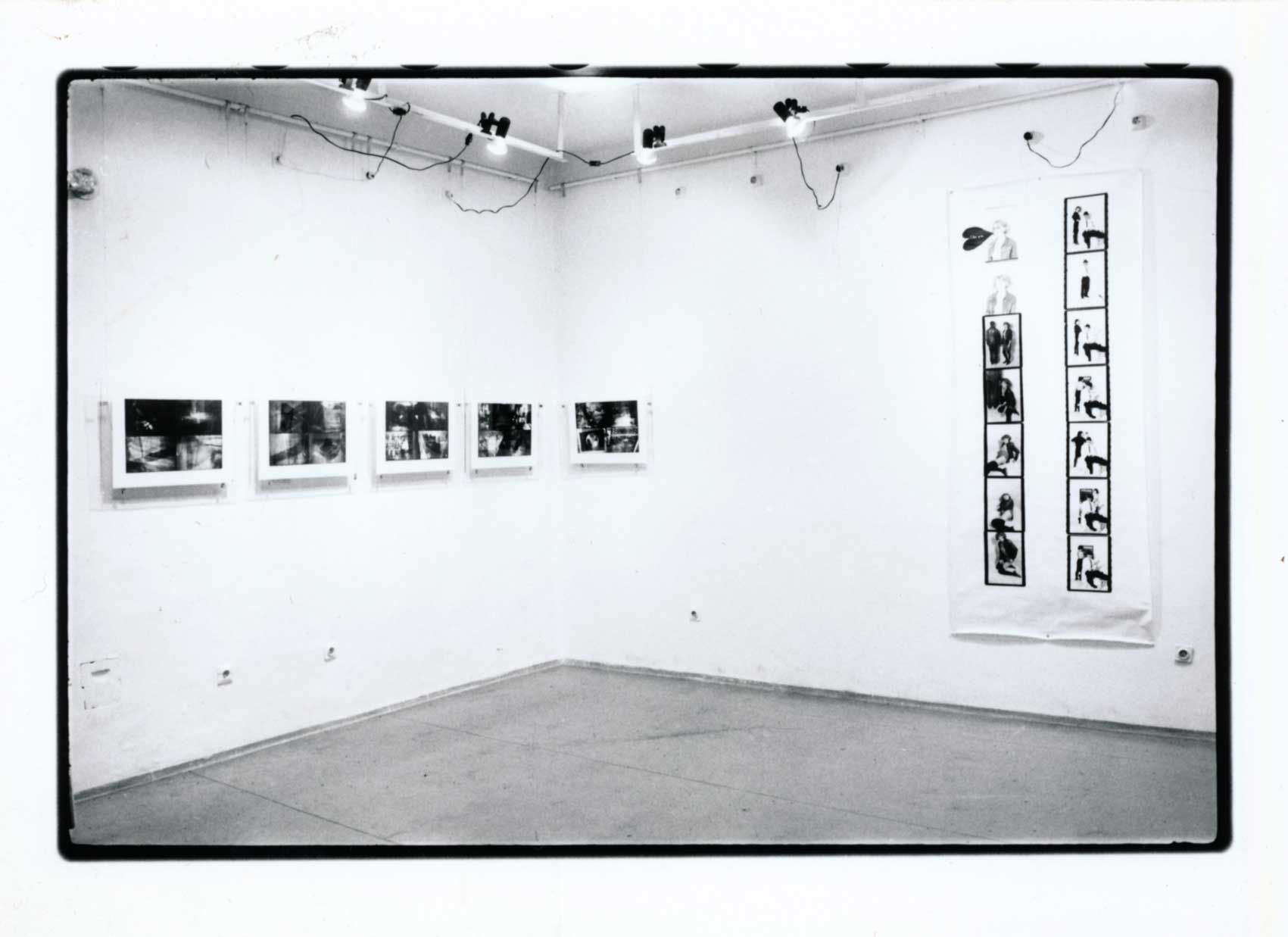

Installation Photos

Floorplans

From the Exhibition

Jacob was utterly unprepared for the attacks, personally and in the press. Out of Eastern Europe traveled widely in the US, and received extensive media coverage. In an article for AfterImage, artist/writer Deborah Bright critiqued the exhibition as paying homage to “the Greenbergian aesthetic and the culturally dominant liberalism it serves.” During a presentation (his first ever) for the annual national conference of the Society for Photographic Education, Ute Eskildsen, curator of photography at the Museum Folkwang, Essen, personally attacked Jacob, repeatedly interrupting him and accusing him of misrepresenting the art of Eastern Europe. In San Francisco’s Artweek, artist Mark Alice Durant wrote of the “knee-jerk, paranoid reaction [with which] some politically correct left-wing academics” were responding to the exhibition.

In a review for the New York Times, photography critic Andy Grundberg observed the exhibition’s relatedness to “Conceptual, Fluxus, Earth, Performance and Correspondence art forms,” making it different more in circumstance than in kind from Western art. For those who accepted its curatorial premise, as being directly related to Jacob’s work as an artist and his interactions with Eastern European artists, the exhibition offered opportunities for revelation. For those who brought to it another set of art historical or geopolitical expectations, it could feel frustratingly neutral. Already in its title, Jacob’s use of the descriptor “private photography” sought to isolate his work and Out of Eastern Europe from the false binary of official/unofficial art and culture. Viewers seeking a stronger political stance by its curator or its artists were disappointed.

The simple premise, that an art of the everyday flourished in Eastern Europe sustained by the enthusiasm of its makers, was the central and most challenging contribution of Out of Eastern Europe. This was an exhibition of works by non-professional artists, made, shared, and exchanged among private or semi-public networks. Visitors who affiliated with conceptual, Fluxus, earth, performance, and mail art saw themselves in the exhibition because, in the West as in the East, those practices were still marginalized in the mid-1980s, operating largely outside the art market. For most visitors, however, what Vaclav Havel labeled Eastern Europe’s “parallel cultures,” distinct to the Soviet Bloc nations but also distinctive from one to another, was unthinkable. An artistic practice not motivated by politics or the marketplace was beyond their experience or their capacity to imagine. Moreover, the inevitable self-positioning of Western viewers as the originators of conceptual, Fluxus, earth art, etc., made anything coming from elsewhere seem duplicative of the West, a copy. Jacob, too, frequently responded from bias. “You [also] had to face up to the preconceptions that American critics had about Eastern art at the time,” Várnagy reminded him in 1995, referring to the criticism of Out of Eastern Europe.

Press

The typewriter was central to Jacob’s early mail art practice. As an artist presenting the work of other artists, he felt compelled to respond to each critic, typing long letters to the editors of newspapers and journals, accepting criticism where it was due and detailing where their writers were misinformed or wrong. Few of the letters were published but, though he did not yet recognize it as such, his dialogue with the public media initiated a process of self-criticism that was transformative. It was a kind of critical thinking that he had never learned at home or in school, that, in time, he developed into an artist-centered curatorial practice. It was this that made Out of Eastern Europe such a transitional event in his career. If he was to continue as a curator, as he had by then decided affirmatively, he would need to wear his authority less lightly. This put Jacob at odds with both the free-for-all principles of mail art and the neutral editorial principles of assembling, which until then had guided his work on the Portfolios. It meant finding a different path for future editorial and curatorial work.

It also put him at odds with some of his colleagues in Eastern Europe, for whom the state was the ultimate editor. Though things differed from one Soviet Bloc nation to another, under state socialism everyone worked for the same boss. The museum curator, the magazine editor, the street cleaner, and the artist all served common professional objectives by all serving the state. Those who chose to work as professional artists received the benefits and endured the limitations of their profession. Others, like Várnagy and Sachse, worked in art related fields (gallerist and teacher, respectively). They did not receive the perks that professional artists enjoyed, such as easy access to inexpensive art supplies. But they were not prohibited from making and sharing art. An active amateur culture was a benefit of living under state socialism. There was no art marketplace, but there were periodicals for amateurs and professionals, different stores for them to obtain supplies, and lively cultural organizations, like the Liget Gallery, that supported non-professional artists with exhibitions, competitions, and other opportunities.

The Liget was among the earliest such spaces to become international in its programming, when Várnagy invited Jacob to present the Second Portfolio in Budapest. For Várnagy, the primary role of the gallerist was to hand the keys of the gallery to an artist, and help facilitate whatever she wanted to do there. It was a deliberately undirected space in an otherwise highly directed culture. Out of Eastern Europe was a slight narrowing of the door that was opened to Jacob in Budapest. He excluded emigre artists altogether, and limited contributors to those working in the Soviet Bloc nations (which eliminated Yugoslavia) where he was able to travel freely (which eliminated Romania, Bulgaria, and the USSR). He deferred Soviet photography to its own exhibition, should that prove possible. And he sought to feature artists whose conceptual and media-based work with photography arose as an art of resistance within an evolving socialist aesthetics, but who did so as outsiders through their non-professional status, through the freedoms and limitations on amateur artists. Ultimately, the core of Out of Eastern Europe was the material originally exhibited in Budapest. It was the first of three large survey exhibitions that Jacob organized related to Eastern Europe. The second was Chimaera: Aktuelle Photokunst aus Mitteleuropa (1997), and the third/last Recollecting a Culture: Photography and the Evolution of a Socialist Culture in East Germany (1999), both organized with the Staatliche Galerie Moritzburg Halle. Between them, he focused on individuals and small groups of artists, working in and responding to an Eastern Europe transformed by the political changes of 1989.

In anticipation of its thirtieth anniversary, in 2016 Jacob and Várnagy proposed a re-hanging of Out of Eastern Europe at the Ludwig Museum, Budapest. Tentatively titled Long Journey: Re-Staging Histories, the effort was not successful. Nevertheless, work on that proposal resulted in Jacob and Várnagy drafting a timeline of their corresponding projects in the 1980s and 1990s.

Out of Eastern Europe: Private Photography (Open/Download PDF)

January 17 – April 12, 1987

List Visual Arts Center at MIT, Cambridge, MA

Contributors (by country):

Czechoslovakia:

Karel Bartonicek, Ivan Kafka, Milan Knizák, Libor Krejcar, Tomás Ruller, Rudolf Sikora, Peter Zupnik

East Germany:

Thomas Florschuetz, Leupold/Leupold, Andreas Prüstel, Karla Sachse, Gundula Schulze

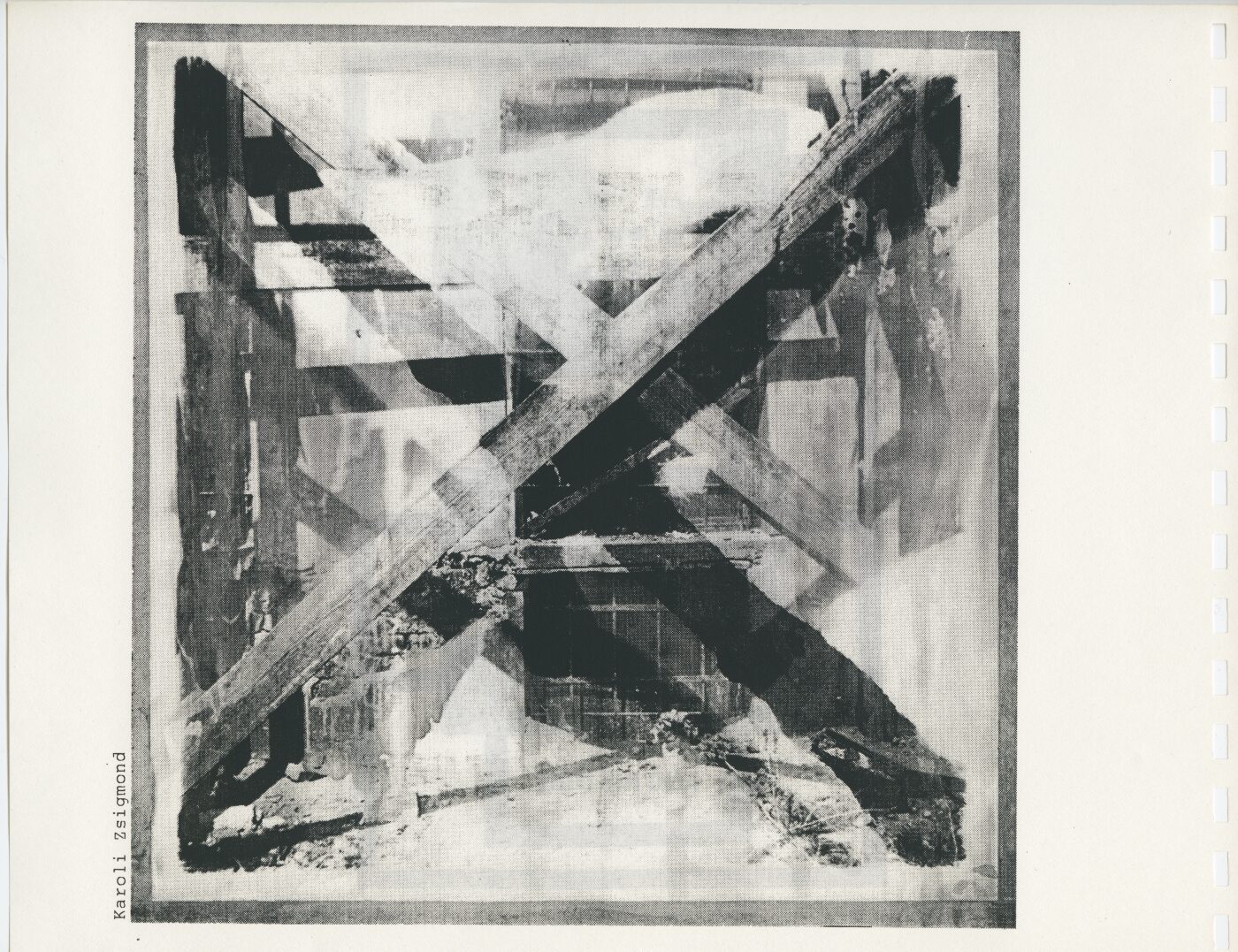

Hungary:

Frankl Aljona, Hajas Tibor, Halas István, Hegedüs 2 László, Károlyi Zsigmond, Miklós Novottny, Schmall Károly, Szilágyi Lenke, Várnagy Tibor, Zátonyi Tibor

Poland:

Janusz Bakowski, Anna Bohdziewicz, Jerzy Caryk, Lucjan Demidowski, Józef Robakowski, Zofia Rydet, Zygmunt Rytka, Antoni Zdebiak

Texts: Katy Kline, JP Jacob, and Lyn Zelevansky

Exhibition Venues:

List Visual Arts Center, MIT, Cambridge, MA; Grey Art Gallery at New York University, New York, NY; Art Space, San Francisco, CA; Salina Art Center, Kansas City, MO; Painted Bride Art Center, Philadelphia, PA;

Baxter Art Gallery, Maine College of Art, Portland, ME

Parallel Exhibitions, US:

In conjunction with Out of Eastern Europe, Jacob organized one-person exhibitions by Anna Bohdziewicz at the Photographic Resource Center, Boston, MA, the Area Gallery, University of Southern Maine, Portland, and the Red Eye Gallery, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence; by Matthias Leupold (GDR) at the Maine College of Art, Portland; and by Thomas Florscheutz (GDR) at the Anderson Art Gallery, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA.

During its presentation in New York, Jacob organized a parallel exhibition at the Rosa Esman Gallery, introducing works by Klaus Elle (GDR) and Krzysztof Pawela (PL).

Parallel Exhibitions, Hungary:

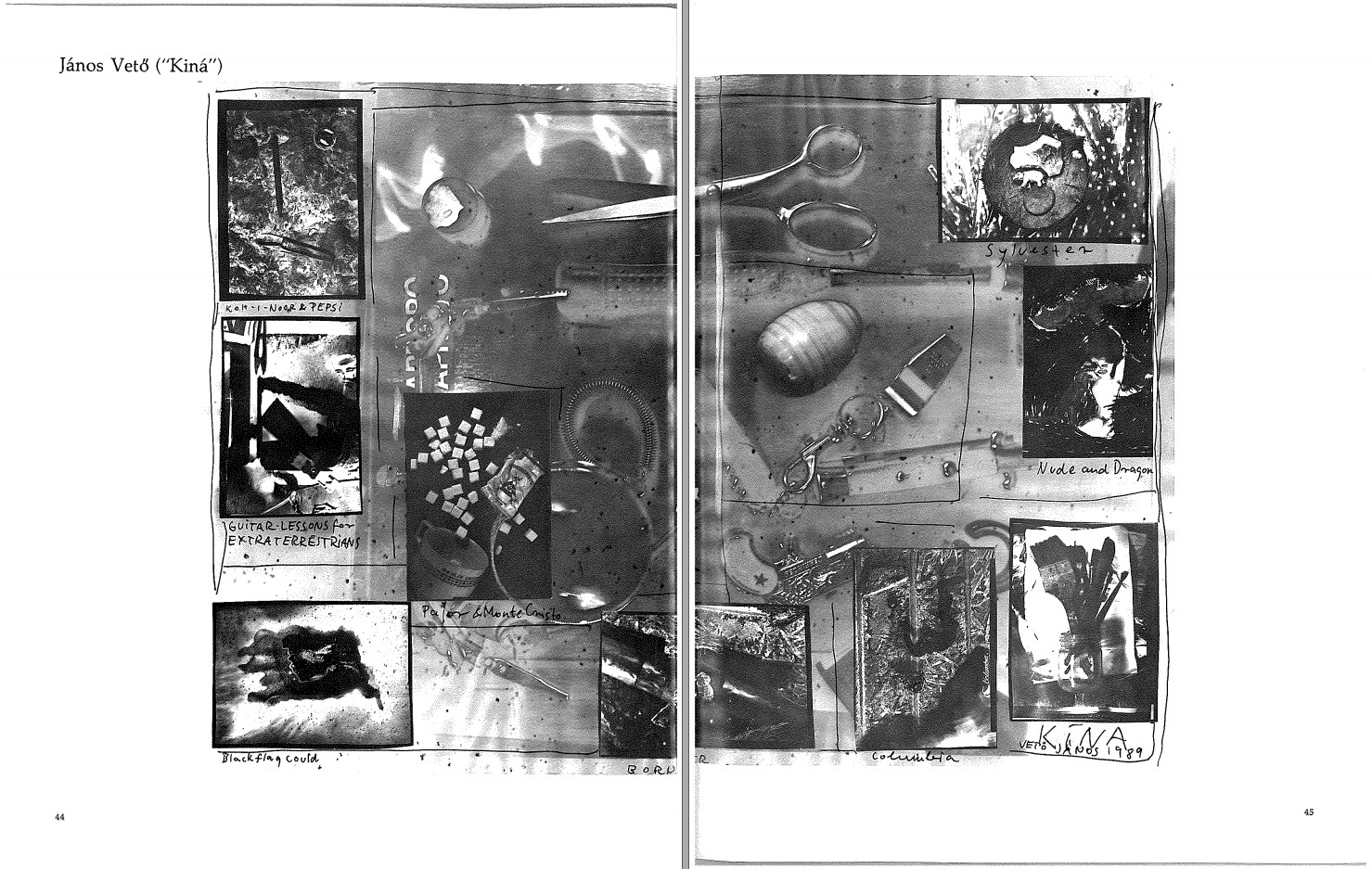

In Budapest, Várnagy organized a parallel exhibition of the Hungarian artists selected for Out of Eastern Europe (including several who were excluded from it: Bálint Flesch, Zoltan Hajtmanszki, Zsuszanna Ujj, and Janos Veto) in October, 1986.

In 1987, Várnagy organized exhibitions by several Second Portfolio participants, including Fireprints by Milan Knizák (CZ), Egotizm by Krystina Ziach (PL), and Fahnenappel by Matthias Leupold (GDR).

Parallel Exhibitions, Poland:

In 1988, Várnagy also organized the first exchange exhibition of Hungarian photo-based works at the Mala Galeria, Warsaw, led by Marek Grygiel. One year later, Grygiel organized an exhibition of Polish works for the Liget Galeria.

Related:

Sherry Miller, Portland Telegram, DATE

Poland

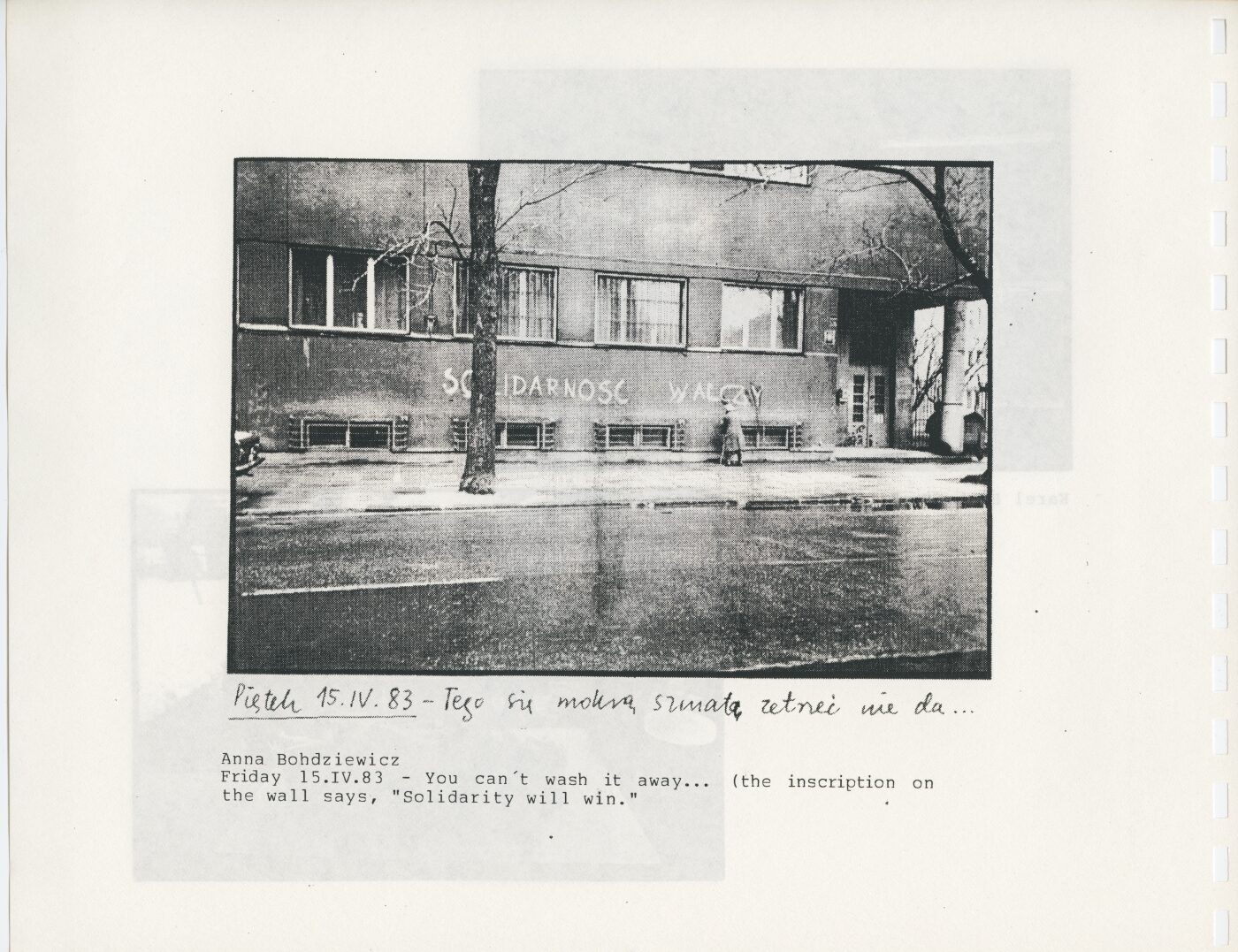

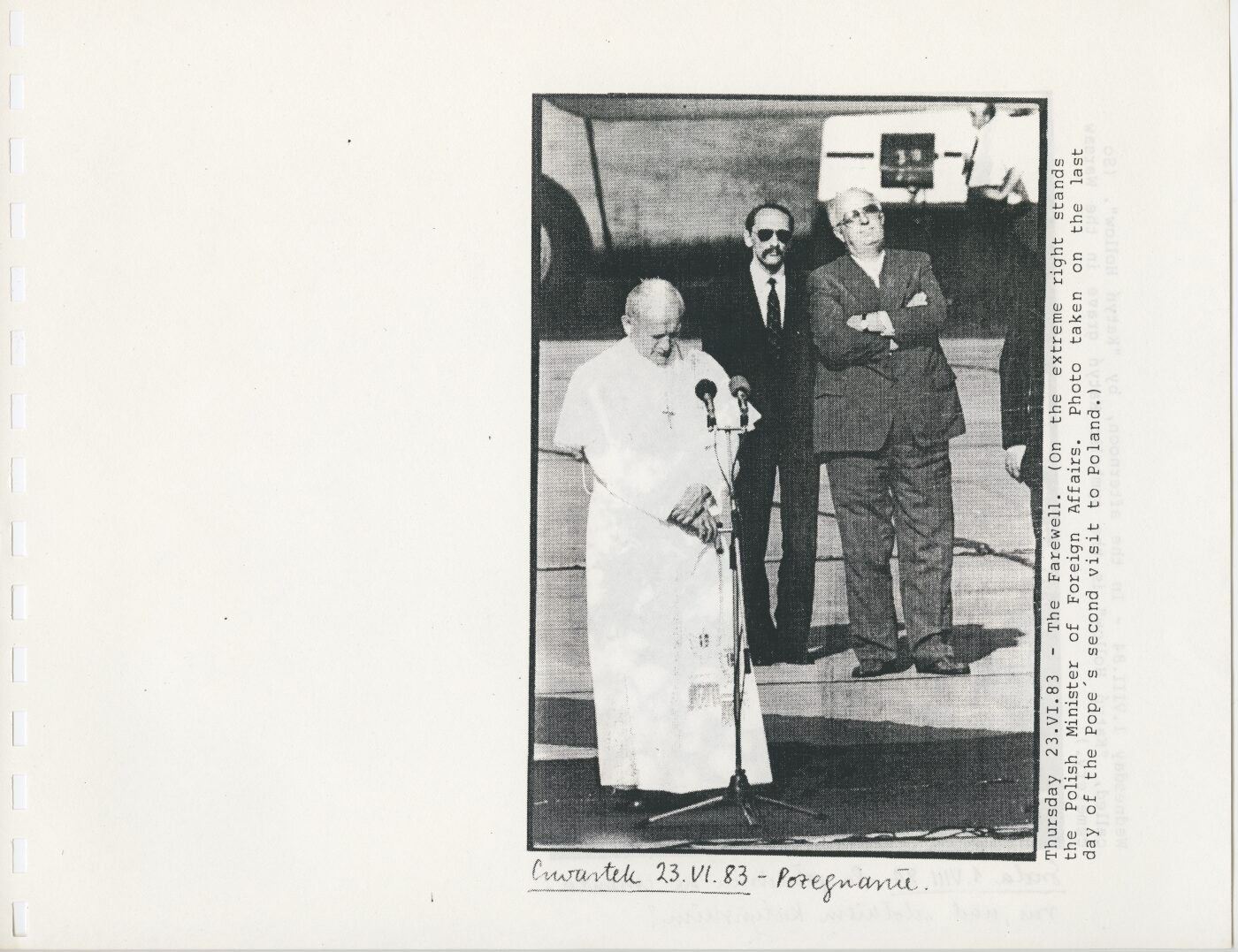

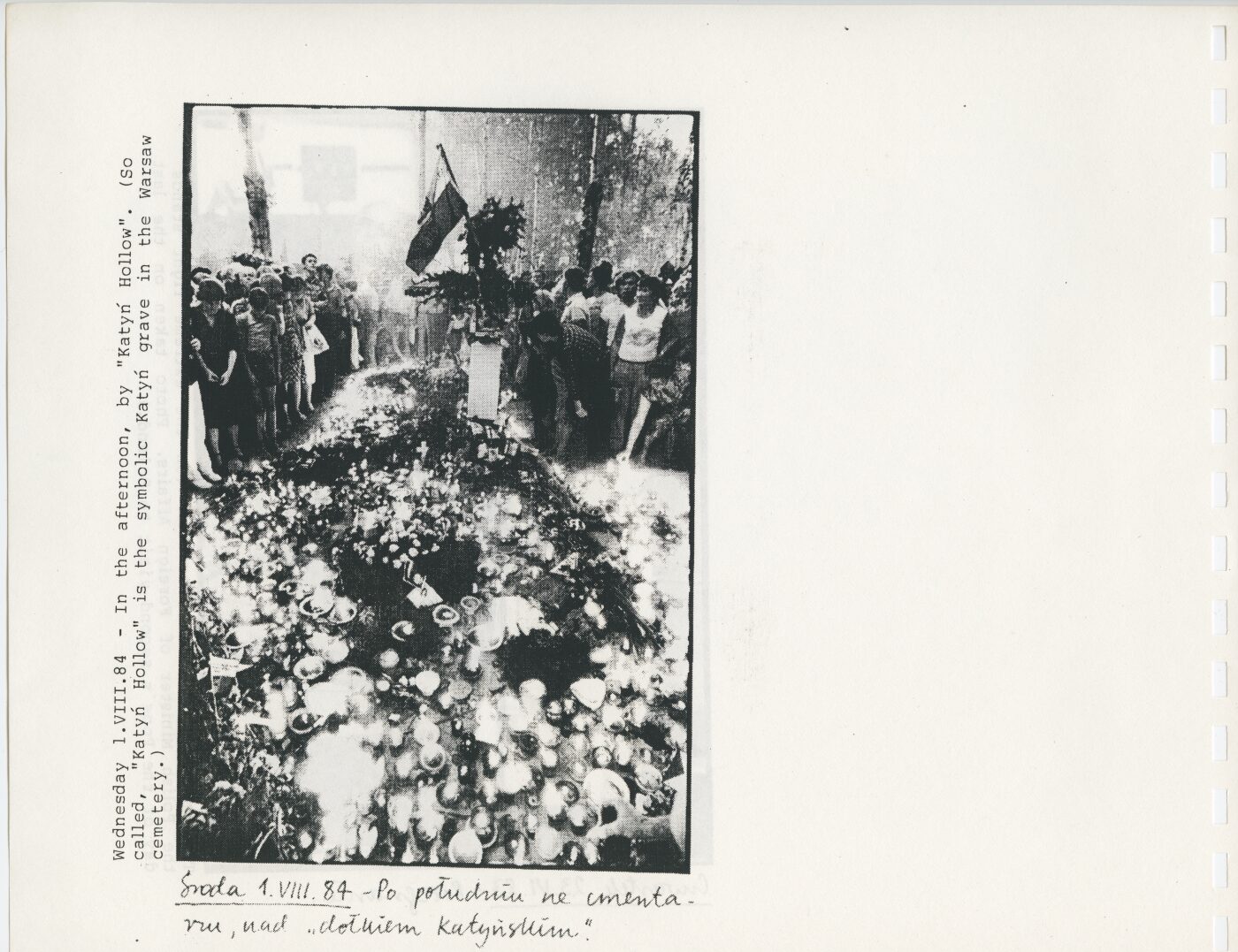

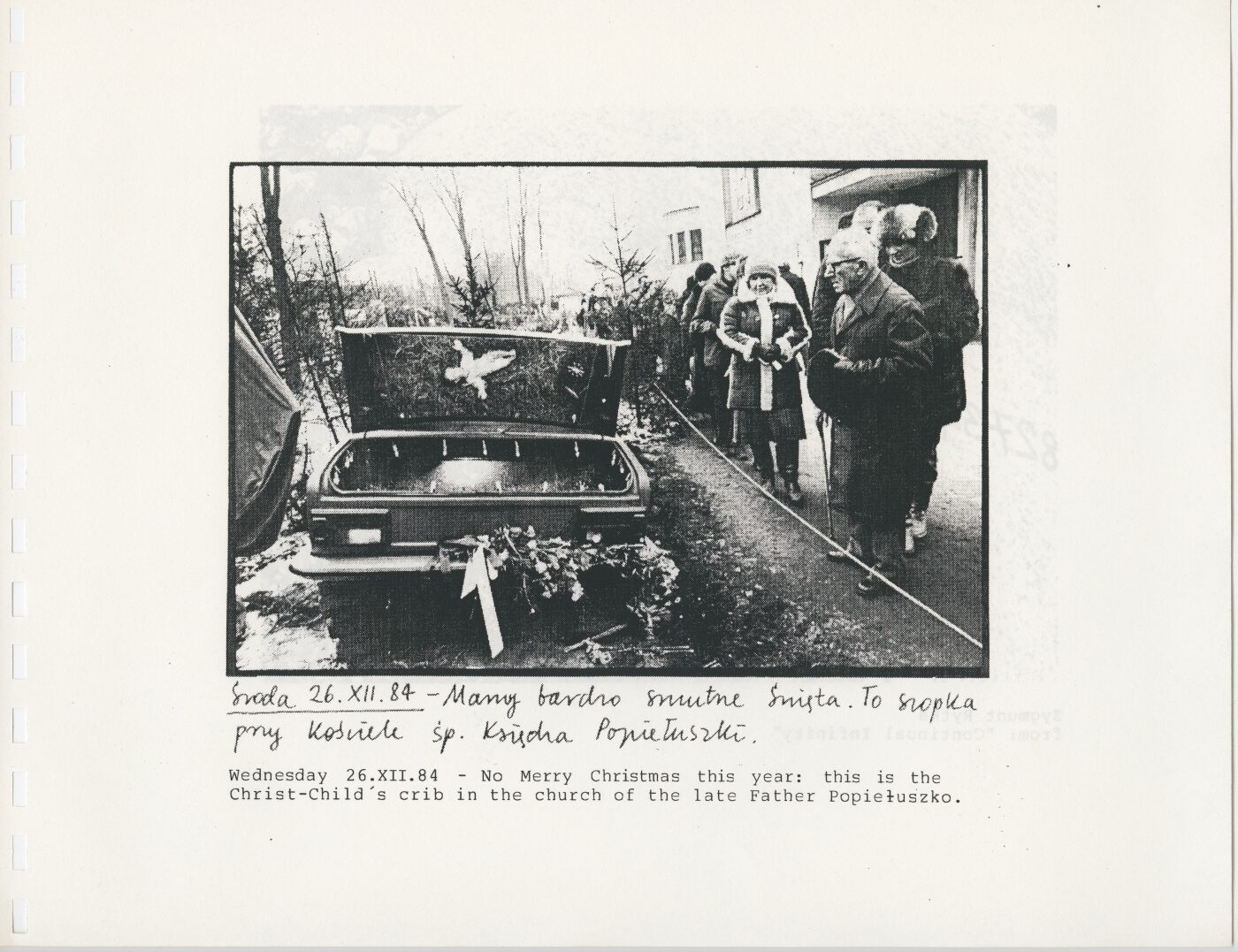

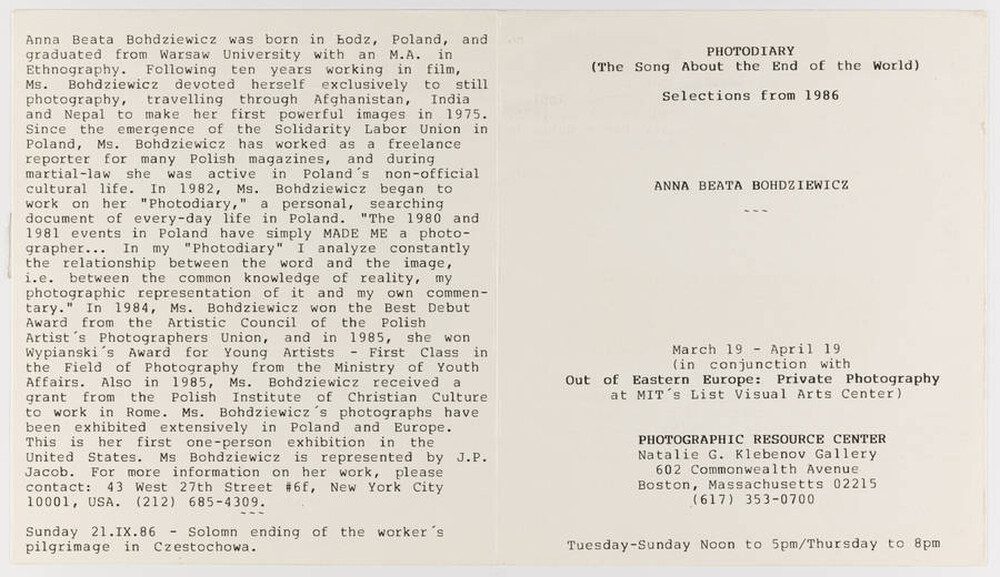

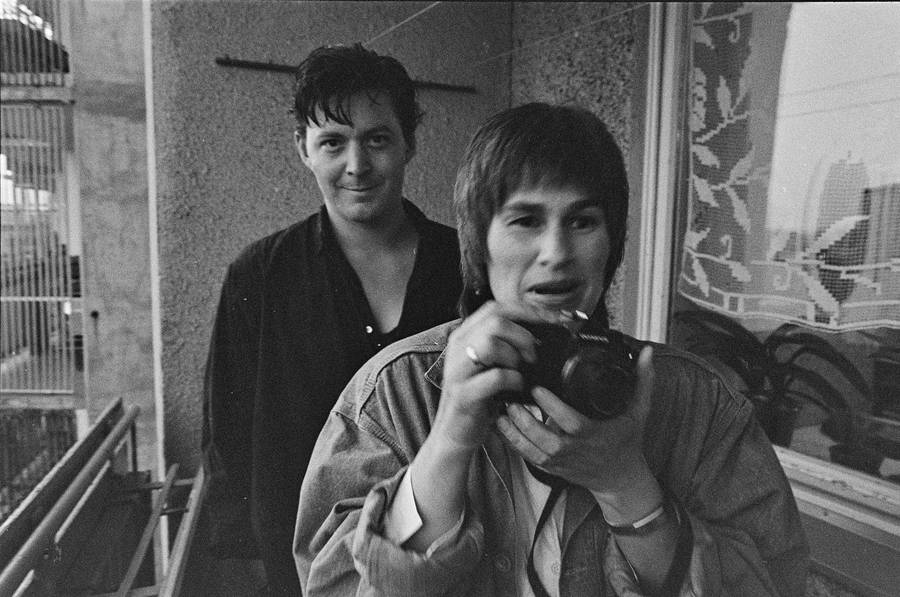

Anna Beata Bohdziewicz: The Photo Diary, or the Song About the End of the World

In Budapest, In September

Marek Grygiel, Warsaw, 2014

Budapest is always a great pleasure to return to. Not only because it is a beautiful and interesting city. It is always a bit of a return to the past.

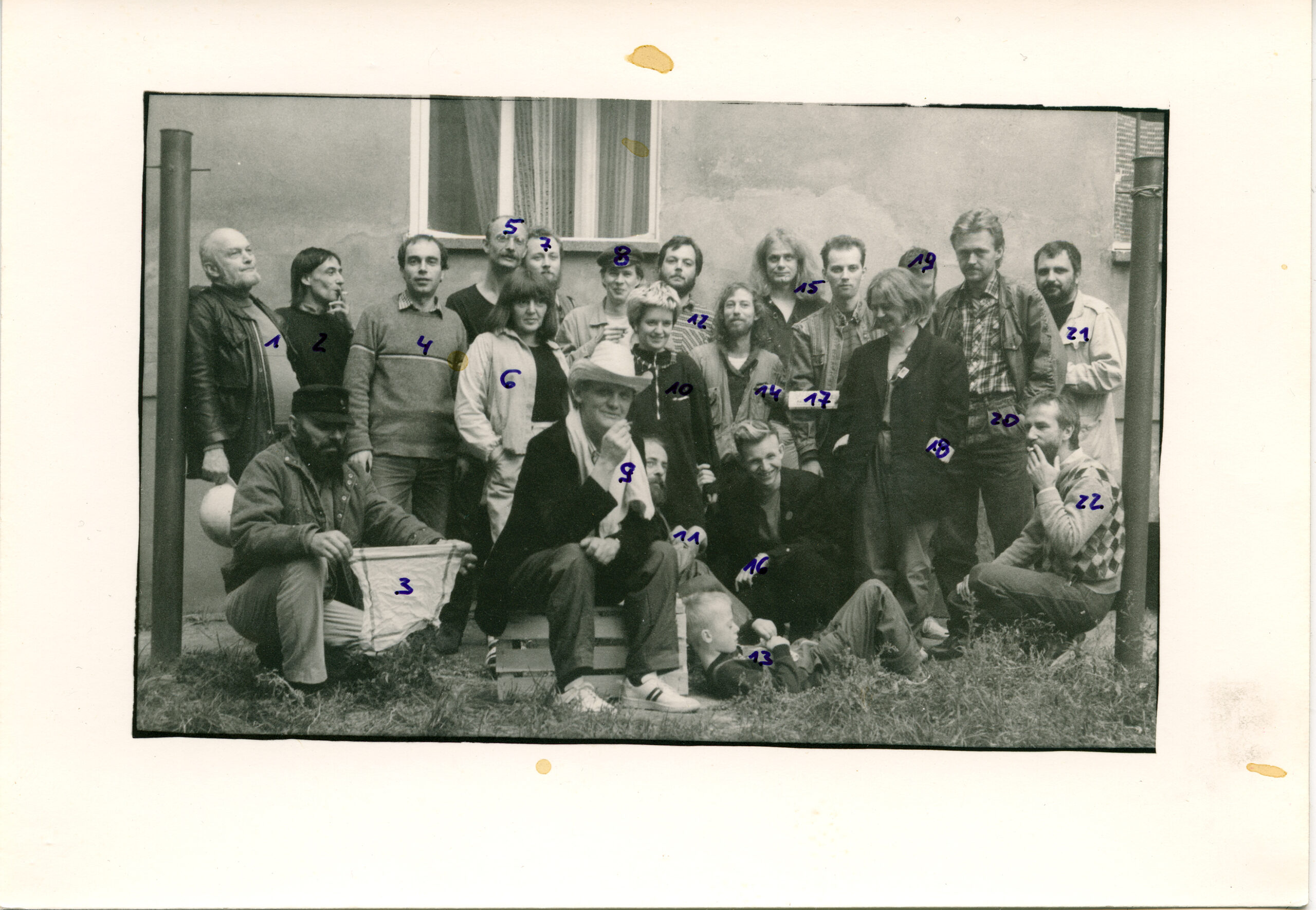

In the late 1980s, a group of Hungarian artists centered around the Liget gallery came with the young American critic and curator John Jacob and Tibor Varnagy to Warsaw and Lodz. The result of this visit was an exhibition that Jacob organized in the U.S. – in short, an exhibition of independent art from Eastern European countries. It was also then that the first contacts and cooperation between Liget Gallery and Mala Gallery in Warsaw began. In June 1987, during the visit of Pope John Paul II to Poland, an exhibition of Liget Gallery artists was held at Mala, and already in the spring of 1988 the first exhibition of Polish artists was held at Liget.

In the years that followed, there were many mutual contacts and artistic endeavors in which many participants took part. A large international group exhibition FOTOANARCHIV, with the participation of Austrian artists as well, the famous happenings of Lodz Kaliska, a trip to Transylvania or the Hungarian province to Szombathely, Miskolc, Szekesfehervar, Zala, which was later reported in Mala Gallery. An exhibition by Gabor Kerekes, a prominent Hungarian photographer who died this year, or the celebration of the Lodz Kaliska exhibition “Let Men Die” at the Center for Contemporary Art in Warsaw with a performance by Zuzsi Ujj and the underground group Csokolom four years ago.

There were many such events. We are adding more to them: Ania Bohdziewicz’s Photo Diary exhibition, which opened in mid-September at Liget Gallery. A gallery that managed to survive the recent period of administrative and political crisis and which, unlike the Mala Gallery (closed by ZPAF in 2006), continues its very rich and interesting program.

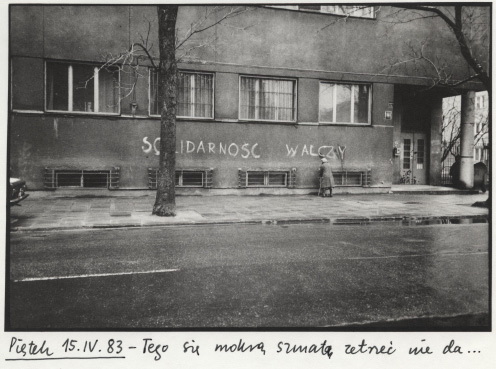

The Photo Diary is a project that the author has been carrying out continuously since 1982. To date, it has already produced 10,000 photos. It is a very authorial, own, sometimes intimate record of everyday life, but also of landmark events that changed the course of history. The author was in the circle of anti-communist democratic opposition, she photographed all the major events, strikes, transformations we have witnessed over the years.

It can be said that this is such a civic-social record, sometimes very lyrical when describing private reality, family, friends, and sometimes sharp and critical, getting into the most heated events of the era. All the photos, accompanied by the author’s own written commentary, constitute a very personal document of the times we live in.

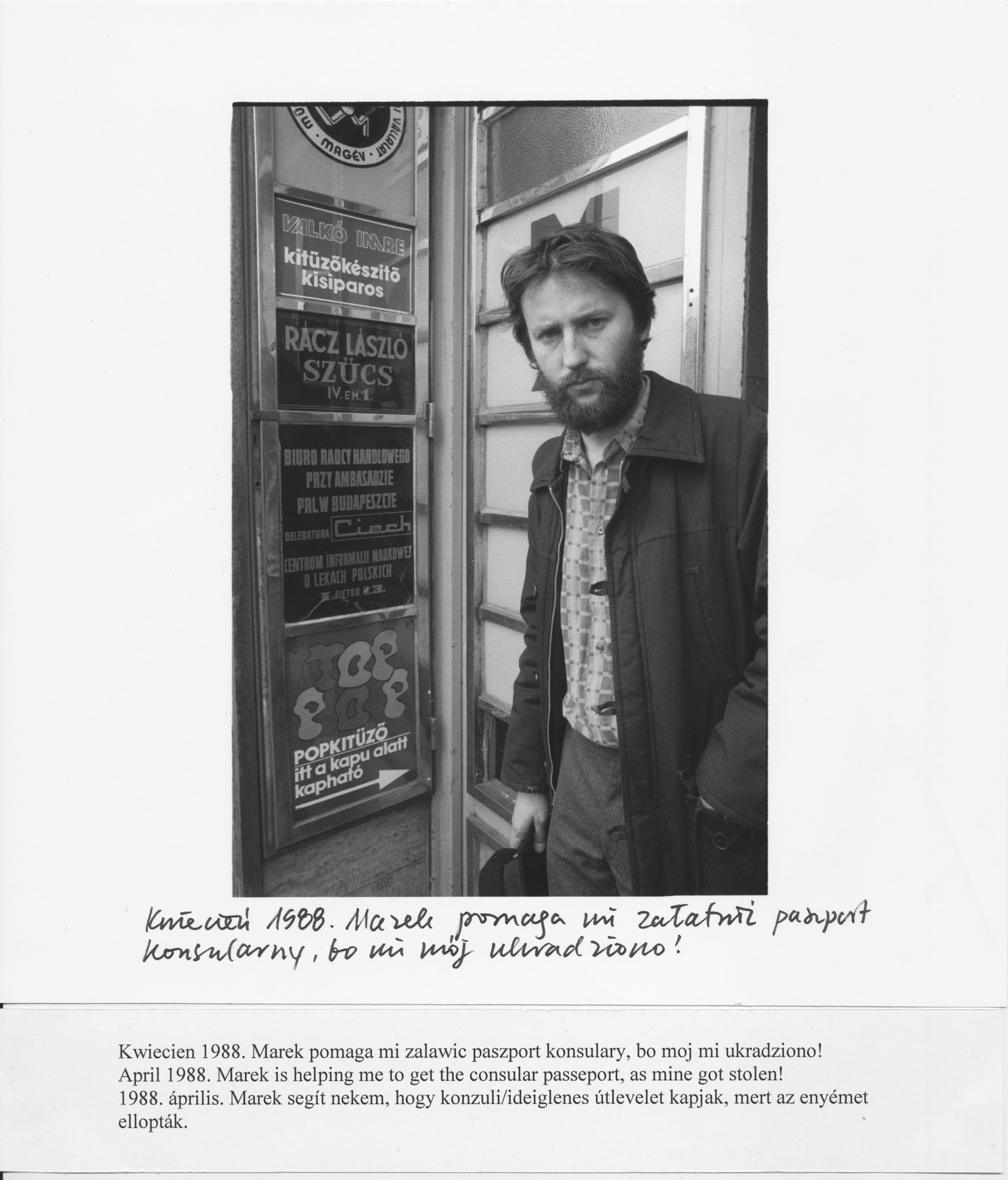

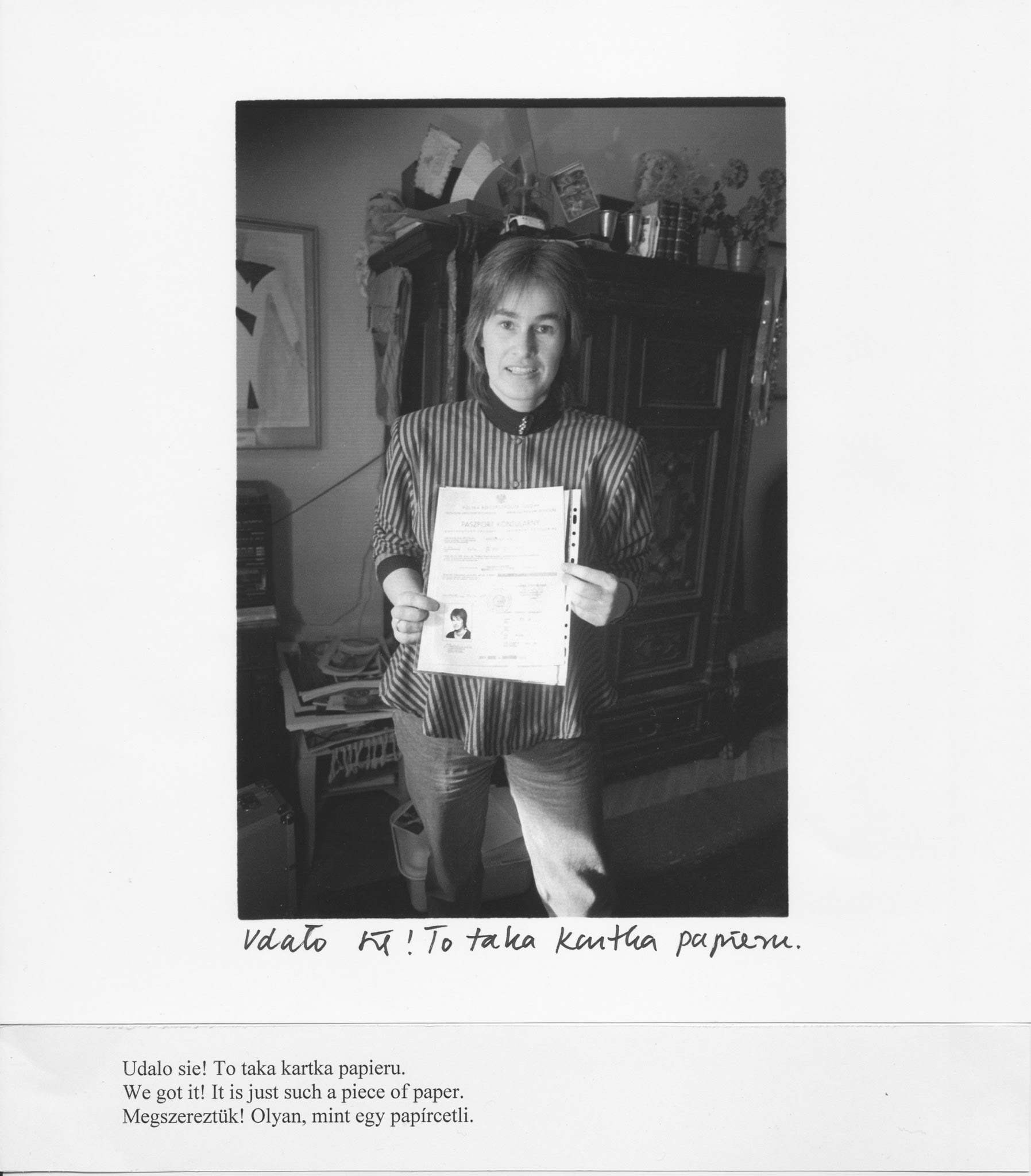

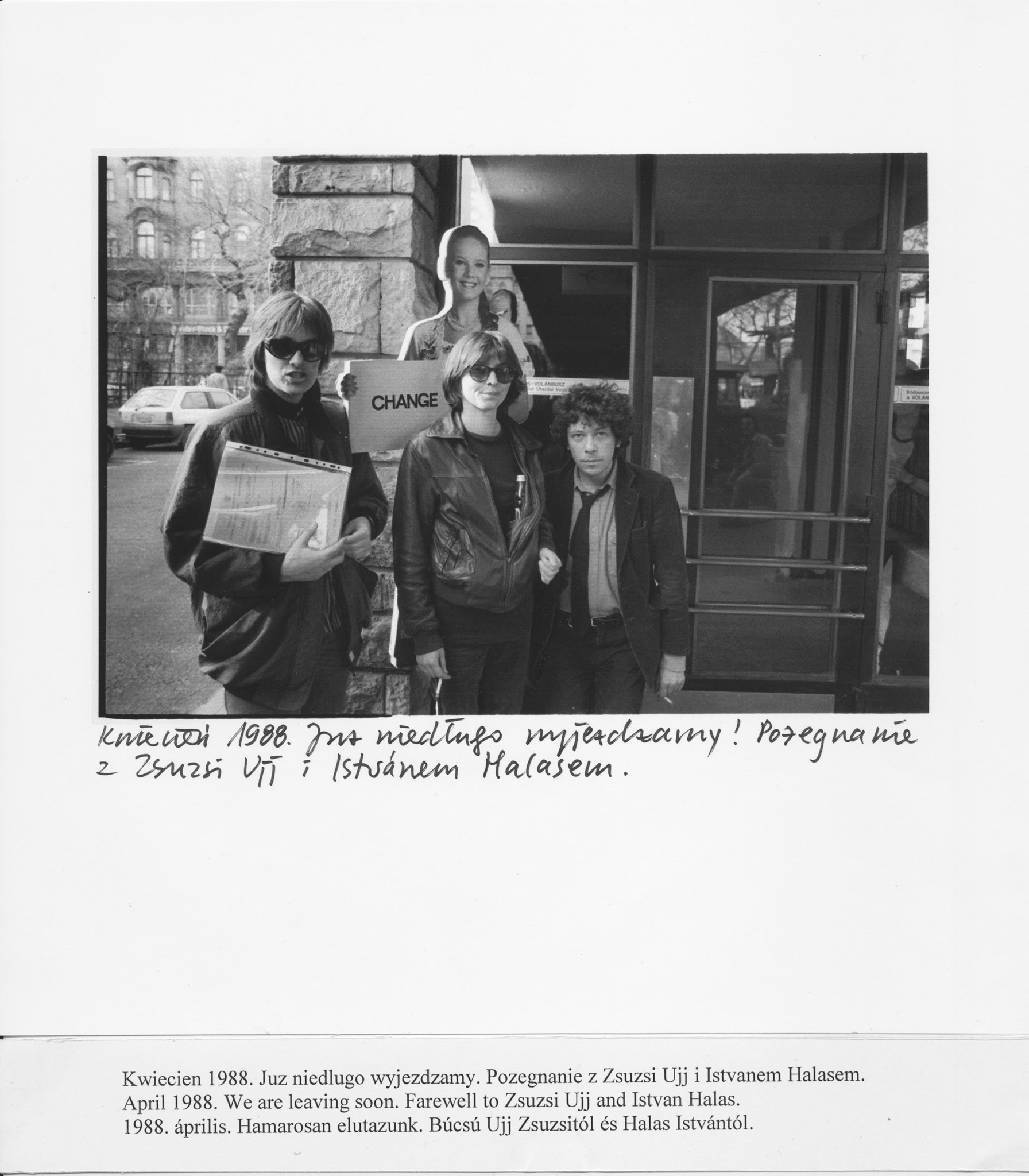

To the 48 selected photographs from these more than 30 years – and it must be said that such a narrow selection is not easy – the author has added an excerpt from her Budapest Photo Diary from 1988, when she was with a group of artists at the Liget Gallery for the first time.

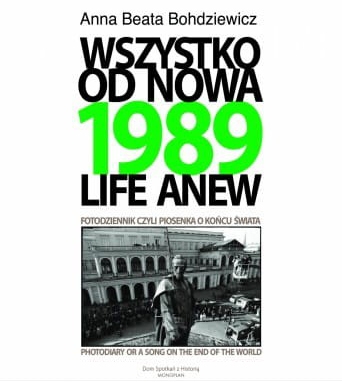

Also on display during the exhibition was an album entitled “Wszystko od nowa/Life anew, 1989,” which will launch a whole series of such publications. Anna Beata Bohdziewicz intends to collect all the yearbooks and publish them in separate volumes. An extremely ambitious, labour-intensive and future-oriented intention. But it will be a priceless record for future generations.

Fototapeta, 2014

https://fototapeta.art.pl/2014/bbu.php

The Photo Diary, or the Song About the End of the World

1987:

Photographic Resource Center, Klebenov Galery, Boston University, Boston, MA

Grey Art Gallery, New York University, New York, NY

1988:

Center Gallery, University of Southern Maine, Portland, ME

Randolph Street, Chicago, IL

1989:

Red Eye Gallery, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, RI

Related:

1986

The Second International Portfolio, Liget Galeria, Budapest

1987

Out of Eastern Europe: Private Photography, List Visual Arts Center at MIT, Cambridge, MA

Private Photography from Eastern Europe, Rosa Esman Gallery, NYC

1988

Polish Experimental Photography, Liget Galeria, Budapest

1997

Chimaera: Aktuelle Photokunst aus Mitteleruopa, Staatliche Galerie Moritzburg Halle

2014

Anna Beata Bohdziewicz: The Photo Diary, Liget Galeria, Budapest

Liget Gallery page:

GDR

Jacob also worked extensively in East Germany in the late 1980s. He was less successful there because American institutions were skeptical that a parallel culture could exist in the repressive GDR, and unwilling to support projects that rejected the binary of official/unofficial art.

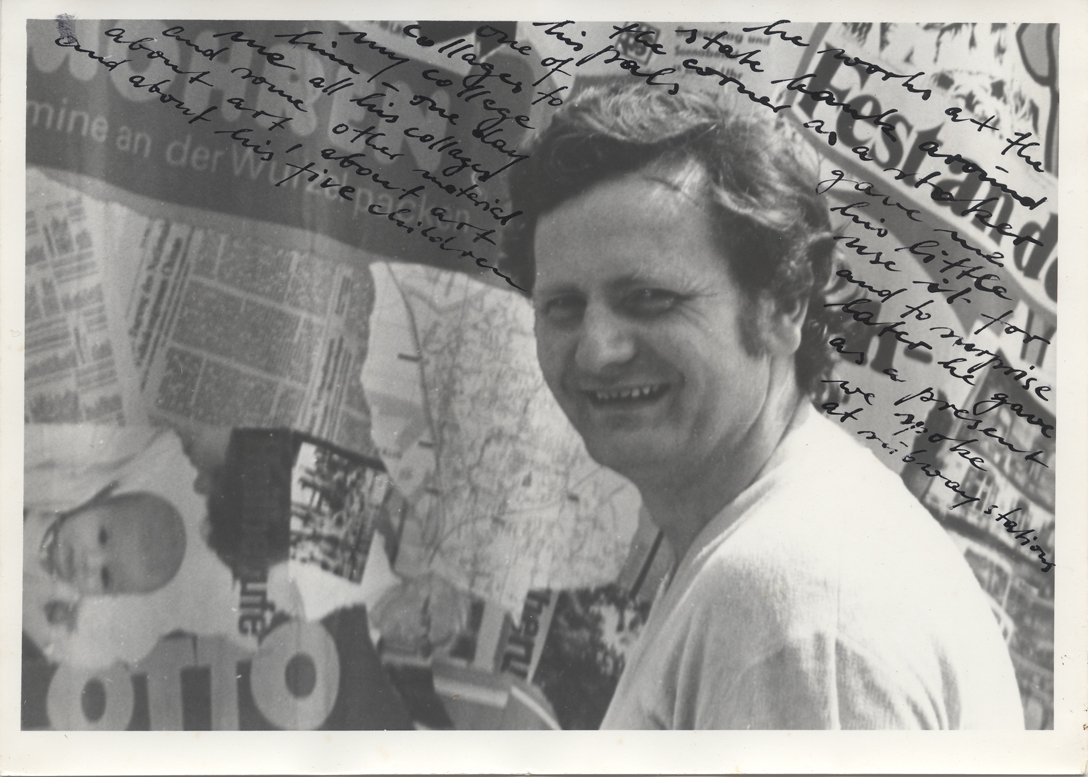

Jacob’s earliest contacts in the GDR were Robert Rehfeldt and Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt. He invited them to contribute to the 1st Portfolio, and, though correspondence with Robert, he learned of the limits on East German artists, prohibited by law from making multiples over a certain number without authorization. It was not prohibited to mail Jacob a negative, however, so Robert did just that, and Jacob printed Rehfeldt’s contribution of seventy-five prints to his specifications. That elegant solution was applied directly to Jacob’s concept for the 2nd Portfolio, for which artists were invited to send a negative or series of negatives that he would print and assemble for them. When Jacob first traveled to East Germany in 1986, he made plans to stay with Robert and Ruth in Berlin. A change of schedule for them resulted in Jacob staying with Joseph Huber and Karla Sachse, with whom he became close friends. Jacob had already corresponded with Huber, and included his work in PostHype 3.1 and the artist’s book Unsolicited Hype. Like Várnagy in Budapest, Sachse became a partner in Jacob’s ongoing work in Eastern Europe.

Jacob was introduced to Thomas Florscheutz, Matthias Leupold, and Gundula Schulze during his first visit to the GDR, by Sachse and Huber. All were included in Out of Eastern Europe. When it traveled to its second venue, the Grey Art Gallery at New York University, Jacob organized a parallel exhibition at the Rosa Esman Gallery, with them, montage artist Andreas Prüstel, and Klaus Elle, whom Jacob had met too late to include in the MIT exhibition. Florscheutz won First Prize for New Photography by European Photography magazine in 1987, and was among the first East German photographers to receive international recognition. Jacob introduced him to Jeffrey Hoone at Light Works in Syracuse, NY, and to Steven High at the Anderson Art Gallery, Richmond, VA. High had hosted Out of Eastern Europe at the Baxter Art Gallery, Portland, ME, where Jacob also organized a parallel exhibition of staged photographs by Leupold/Leupold. Florscheutz was later invited for a residency at Light Works, and, after High moved on to the Anderson, a one-person exhibition there; Jacob contributed a catalog essay to the latter. (In 1989, Florscheutz was included in New Photography V at the Museum of Modern Art, NY.) On his second trip in 1986, to prepare for Out of Eastern Europe, Schulze entrusted Jacob with a portfolio of her prints to carry to Robert Frank, who had recently met with photographers in East Berlin and would become an active supporter of her work.

The photography of Gundula Schulze, one of Germany’s most famous and acclaimed photographic artists, first appeared in Poland in the mid-1980s. It was then that American John P. Jacob and Hungarian Tibor Varnagy visited Warsaw and Lodz. Their visit was connected with collecting and searching for works of independent photographers for a large exhibition of photography and art of Central European countries. This exhibition was later presented at M.I.T/Cambridge Mass. and was one of the first presentations of independent, actually underground art photography of the countries of the so-called People’s Democracy in America. Work on this exhibition resulted in numerous contacts and friendships that have endured to this day ( e.g., regular contacts between artists centered around the Small Gallery in Warsaw and the Liget Gallery in Budapest). A specific reminder and reference to that situation was the recent (1997) exhibition titled “Chimaera – Aktuelle Photokunst aus Europa” in Halle (reported in Foto Tapeta), also curated by John P. Jacob.

Marek Grygiel, Foto Tapeta, 1999

https://fototapeta.art.pl/fti-gseldowy2.html

Joseph Huber & Karla Sachse

Jacob and Sachse cooperated on several prospective projects. In addition to contributing an essay to Jacob’s unpublished manuscript for the MIT Press, and helping coordinate with other GDR writers (Wolfgang Kil, Christoph Tannert, and Gabrielle Muschter), Jacob and Sachse co-edited a collection of texts and portfolios of East German photography for VIEWS, the journal of the PRC. The collection, Out of Control: Photography from East Germany, included a Foreword by Sachse; “Ostkreuz – An Origin in Stopped Time” by Wolfgang Kil with a portfolio of by Ostkreuz photographs (Sibylle Bergemann, Harald Hauswald, Ute Mahler, Jenz Rotzsch, and Harf Zimmerman); “The Work of Evelyn Richter” by Andreas Krase with a portfolio by Richter; and “The Near Distance – Cultural Otherness in the Two Germanies” by Susanne Klengel with a portfolio by Matthias Leupold. It was published online in 1993, an early web-based publication that Jacob himself coded.

They also worked on one successful and three unrealized exhibitions in the late 1980s and early 1990s, including an ill-fated presentation of I Am Trying to See in East Berlin after it was shown in Budapest. The photographs were confiscated by border police at Friedrichstrasse. The ransom Jacob paid for their return, when he exited the GDR after that visit, was the most ever paid for his photographs. In 1991, Sachse and Jacob were participants in Montage als Kunstprinzip: Colloquium zur John Heartfield, a conference celebrating Heartfield’s centennial at the Akademie der Kunst in Berlin. At that time, they co-curated Photomontage Heute, an exhibition for the Fotogalerie Berlin-Friedrichshain, Berlin.

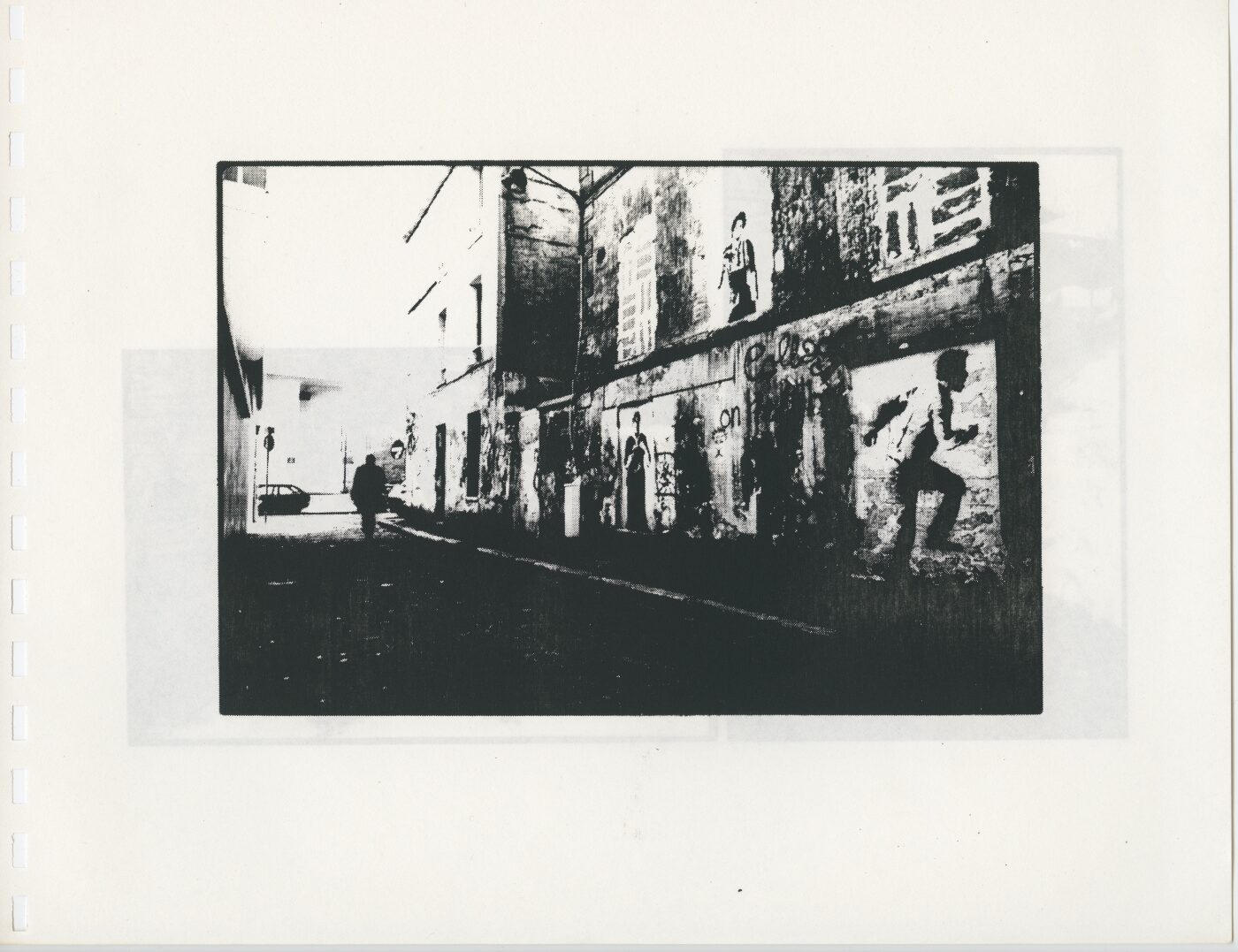

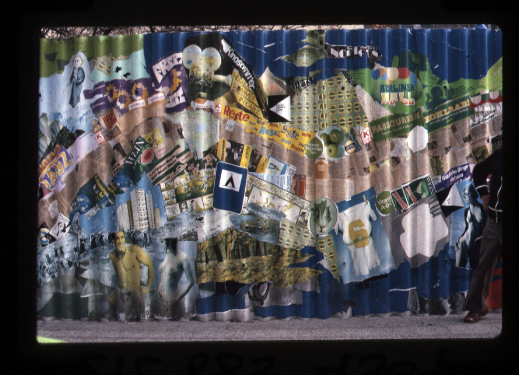

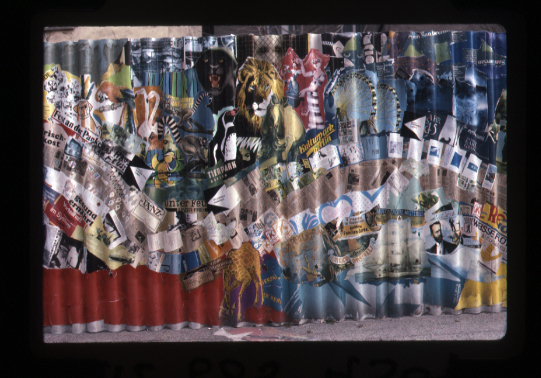

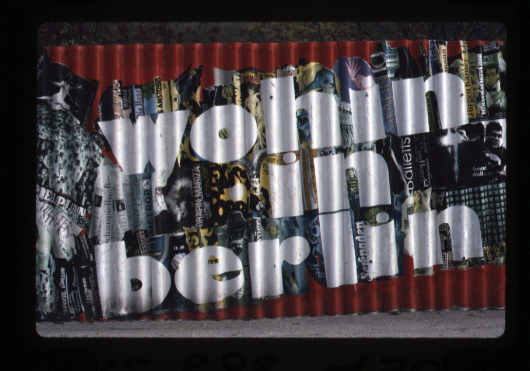

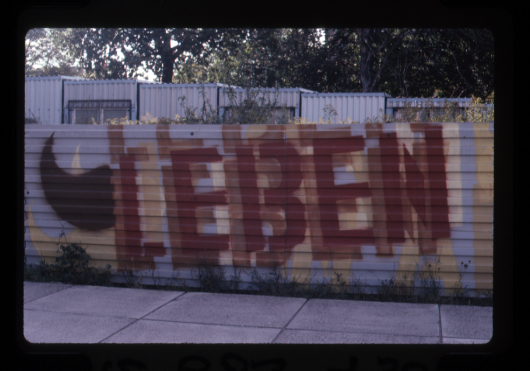

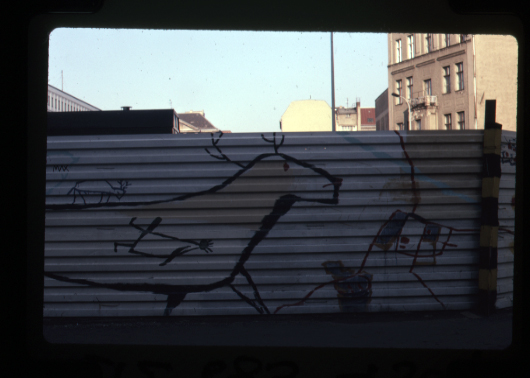

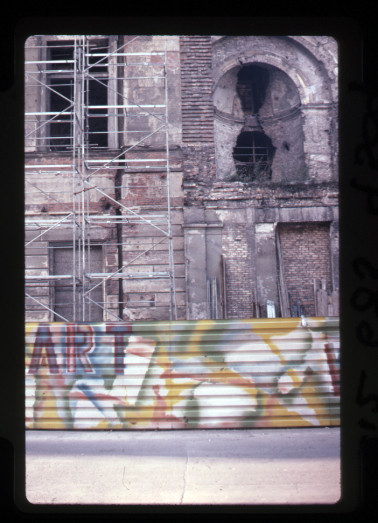

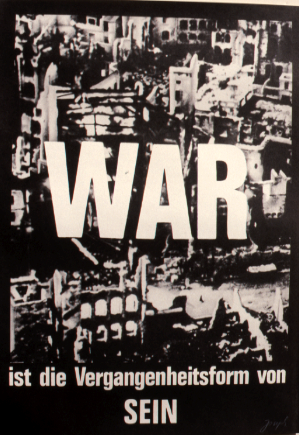

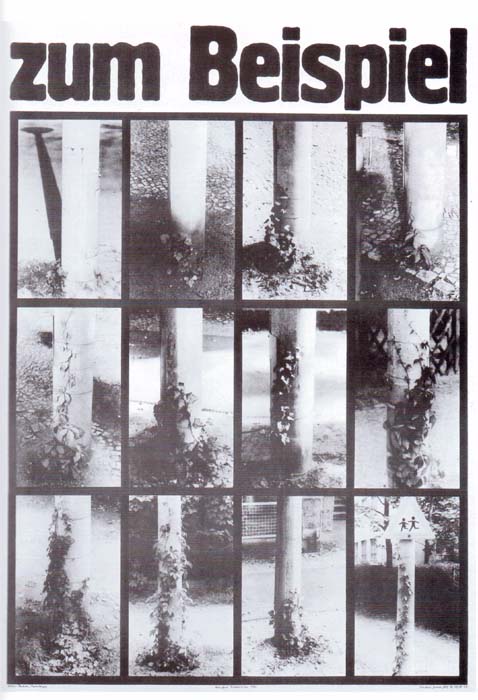

Jacob’s and Sachse’s unrealized exhibition proposals examined Public Murals in East Berlin and East German Artists Working in the Tradition of John Heartfield. Sachse and Huber were active internationally as mailartists and locally as public artists, leaders of a group of artists who took advantage of East Berlin’s unused advertising kiosks, on the street and in the U-Bahn, to show their work. Some brought works from their studios, such as paintings, and hung them in the empty spaces. Others, like Sachse, created unique installations. Sachse documented some of this activity, but Jacob never found a taker for the exhibition, so it never advanced beyond a very preliminary stage of development. The Tradition of Heartfield proposal was fully developed and presented to the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, which ultimately declined it. The artists included Huber and Sachse, as well as Manfred Butzmann, Martin Hoffmann, Andreas Prüstel, Wolfgang Janisch. The exhibition materials (138 objects in total) are held with the John P. Jacob/Riding Beggar Press Papers at the Beinecke Rare Books Library, Yale University.

Joseph Huber

1984

PostHype 3.1

1985

Unsolicited Hype

1986

Second Portfolio (NYC & Budapest versions)

1991

Photomontage Heute, Fotogalerie Berlin-Friedrichshain, Berlin (contributor)

1999

Recollecting a Culture: Photography and the Evolution of a Socialist Aesthetic in East Germany

Karla Sachse

1986

Second Portfolio (NYC & Budapest versions)

1987

Out of Eastern Europe: Private Photography, List Visual Arts Center at MIT, Cambridge, MA

1991

Photomontage Heute, Fotogalerie Berlin-Friedrichshain, Berlin (co-curator)

1993

“Out of Control: Photography from East Germany” online anthology, Photographic Resource Center, Boston, MA

Related

Jacob’s and Sachse’s unrealized exhibition proposals examined Public Murals in East Berlin and East German Artists Working in the Tradition of John Heartfield

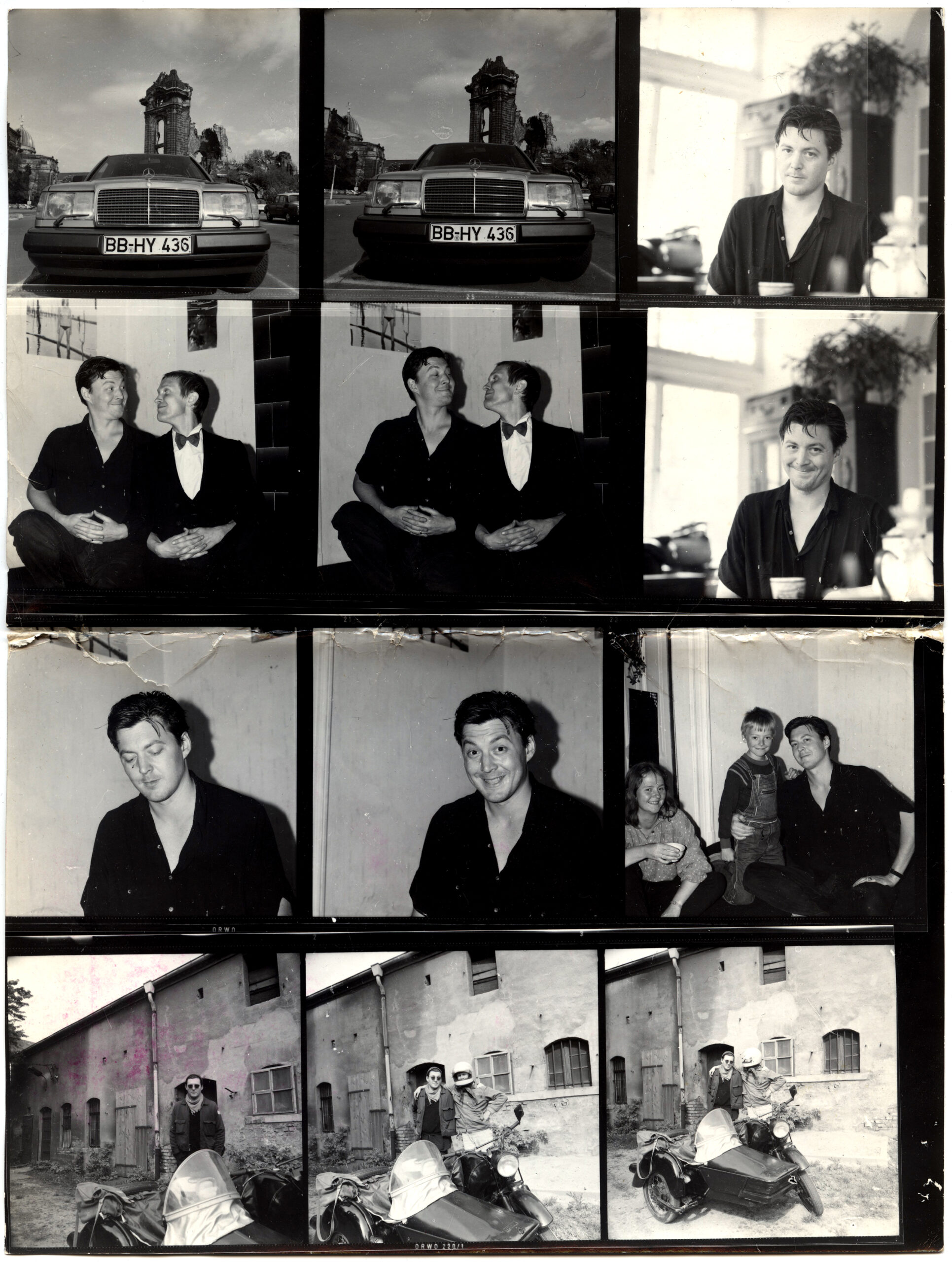

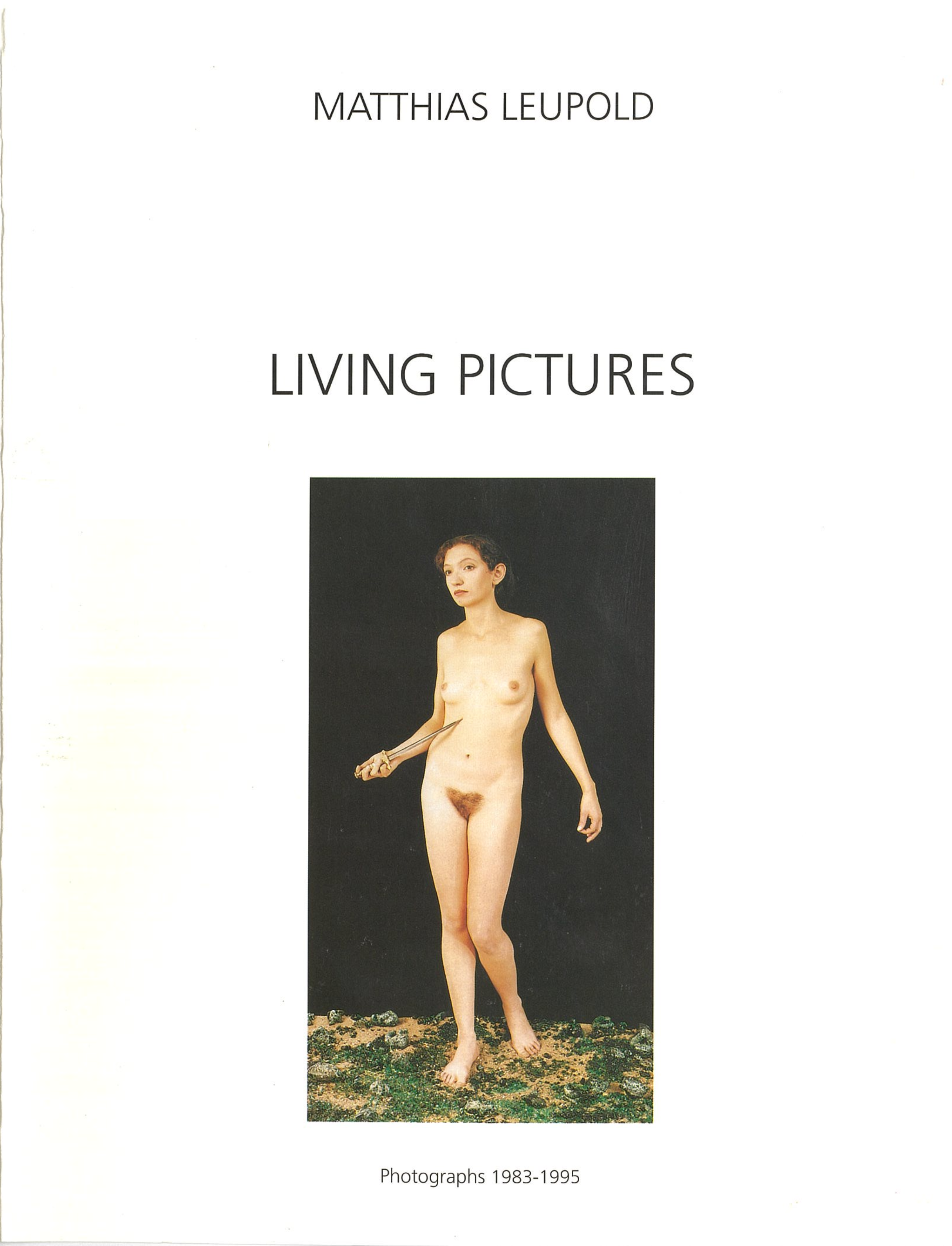

Matthias Leupold: Staged Photographs

Jacob formed immediate and enduring friendships with Matthias Leupold and Andreas Leupold, two unrelated artists who shared the same family name, then collaborating with a third friend, Andreas Hentschel, as Leupold/Leupold. Days before Jacob’s first visit to East Berlin, Matthias Leupold received approval to emigrate to West Berlin; Andreas had emigrated some months earlier. Coming late one night to Sachse’s apartment, Matthias entrusted Jacob with a portfolio of oversized prints. Matthias and Andreas visited Jacob in New York City in 1987, leaving a crate of large prints with Jacob to work with before traveling on to New England to experience “Indian Summer.” Following an idea they’d picked up watching American movies, they bought a used car for a few hundred dollars and, before returning to Berlin, abandoned it on the New Jersey Turnpike.

In late 1988, Jacob drove from Berlin to Budapest with Leupold, Leupold, and Hentschel, for an exhibition of Leupold/Leupold’s Fahnenappell organized by Várnagy at the Liget Gallery. Jacob also presented Leupold’s series Gartenlaube and Fahnenappell at the Photographic Resource Center (PRC) at Boston University in 1995, and contributed an essay to the exhibition catalog for Leupold’s Living Pictures in 1997. Leupold was also included in Jacob’s exhibition CHIMAERA: Aktuelle Photokunst aus Mitteleuropa, in 1997, for the Staatlichte Galerie Moritzburg Halle, and in Recollecting a Culture: Photography and the Evolution of a Socialist Aesthetic in East Germany, in 1999 at the PRC. Both exhibitions were organized with T.O. Immisch, photography curator for the Staatlichte Galerie Moritzburg Halle, to whom Jacob was introduced by Sachse and Huber in the 1980s. Immisch would be a key collaborator with Jacob in the 1990s.

Staged Photographs

1988

Maine College of Art Gallery, Portland, ME

Related:

1987

Out of Eastern Europe: Private Photography, List Visual Arts Center at MIT, Cambridge, MA

Private Photography from Eastern Europe, Rosa Esman Gallery, NYC

1995

Leupolds Gartenlaube & Fahnenappell. Leupold’s Allotment & Flag Raising Ceremony. Photographic Resource Center at Boston University, MA

1996

“Introduction” (catalog essay for Matthias Leupold: Living Pictures 1983-1995, Stipendiat im Künstlerdorf Schöppingen, Germany)

1997

Chimaera: Aktuelle Photokunst aus Mitteleruopa, Staatliche Galerie Moritzburg Halle, D

1999

Recollecting a Culture: Photography and the Evolution of a Socialist Aesthetic in East Germany. Photographic Resource Center at Boston University, MA

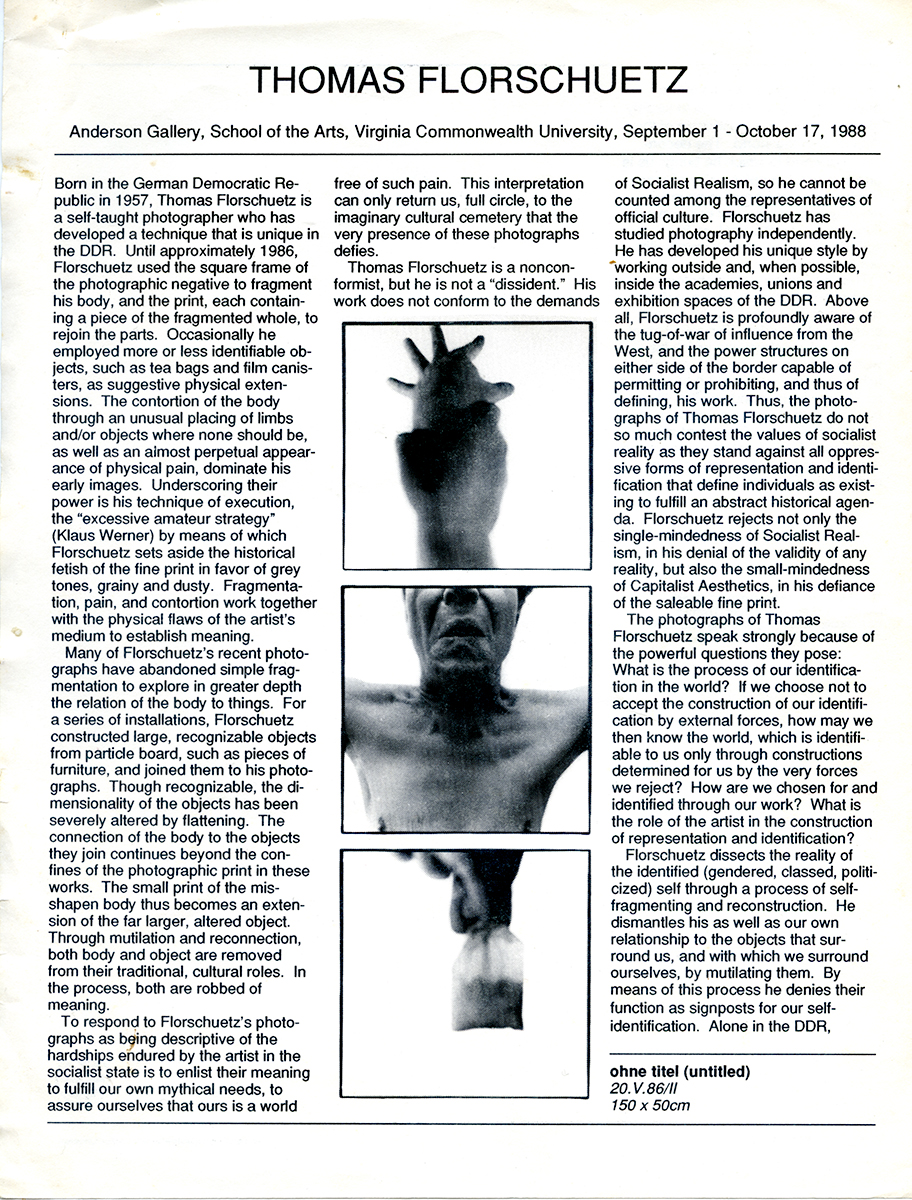

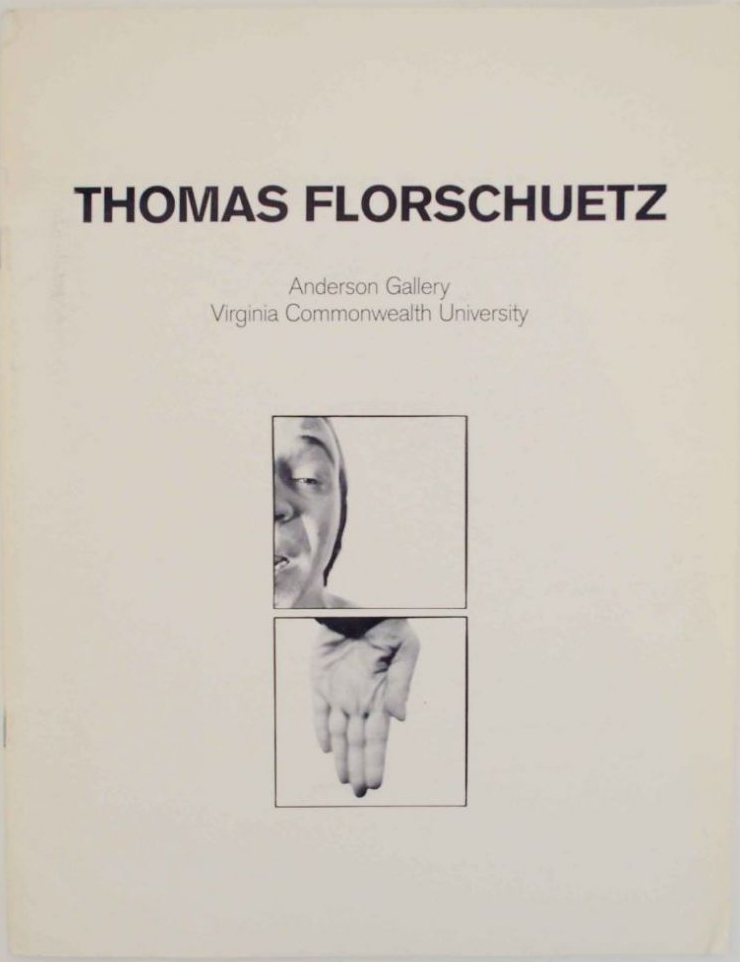

Thomas Florscheutz: Extracting Meaning from Myth

John P. Jacob, Austin, TX, 1988

Western audiences may be surprised to learn that many of the younger generation of artists from the nations we know as “Eastern Europe” regard their attentions with wariness. Frequent past misuses have damaged not only the artists’ self esteem but often, too, the artists’ future possibilities for exhibitions. Little better serves the sentimental purposes of Western propaganda, however, than the enigmatic and disquieting images these artists produce. Isolated from their original intentions by the walls of the museum or gallery, these works appear to offer a profound reinforcement of the gothic spectres of censorship and the “cultural cemetery” (Heinrich Boll), which are our comprehensive understanding of artistic possibility in these nations.

But censorship is no longer the lethal force that it was in the days of Stalin, and Eastern Europe no longer the cultural cemetery of our imagination. Indeed, the artist has become an important and privileged member of the socialist state, and is allowed freedoms unimaginable even a few short years ago. Today, “independent spaces” or “workshops” exist in most Eastern European nations where younger artists (artists of all ages who have not been admitted to either the art academies or unions) are encouraged to exhibit and perform unsanctioned works. The best of these artists receive awards and commissions from the state. Later, they may receive official recognition, enabling them to enter the artists’ unions. The reward of membership is the shared responsibility of helping to build the state, of working toward the common good through the power of their medium. Such responsibility transforms the individual from an artist into a “cultural worker,” and the artist’s work from solipsistic to socially relevant, endowed with the powers of utility and influence. With such power is implied the potential of the artist to effect change within his or her culture.

Given these opportunities, it is difficult to understand why so many young Eastern European artists prefer that their works not be classified as referring to social and/or political circumstances, or as representative of their nation’s cultural interests. Instead, these artists regard themselves as engaged in the struggles of the individual within a dominant culture, of identity struggling against identification. What we must understand, they ask, is that the struggle of the self against the immensity of all forms of oppression, such as may be found in all political and economic systems, is the only valid expression of, and witness to, truth.

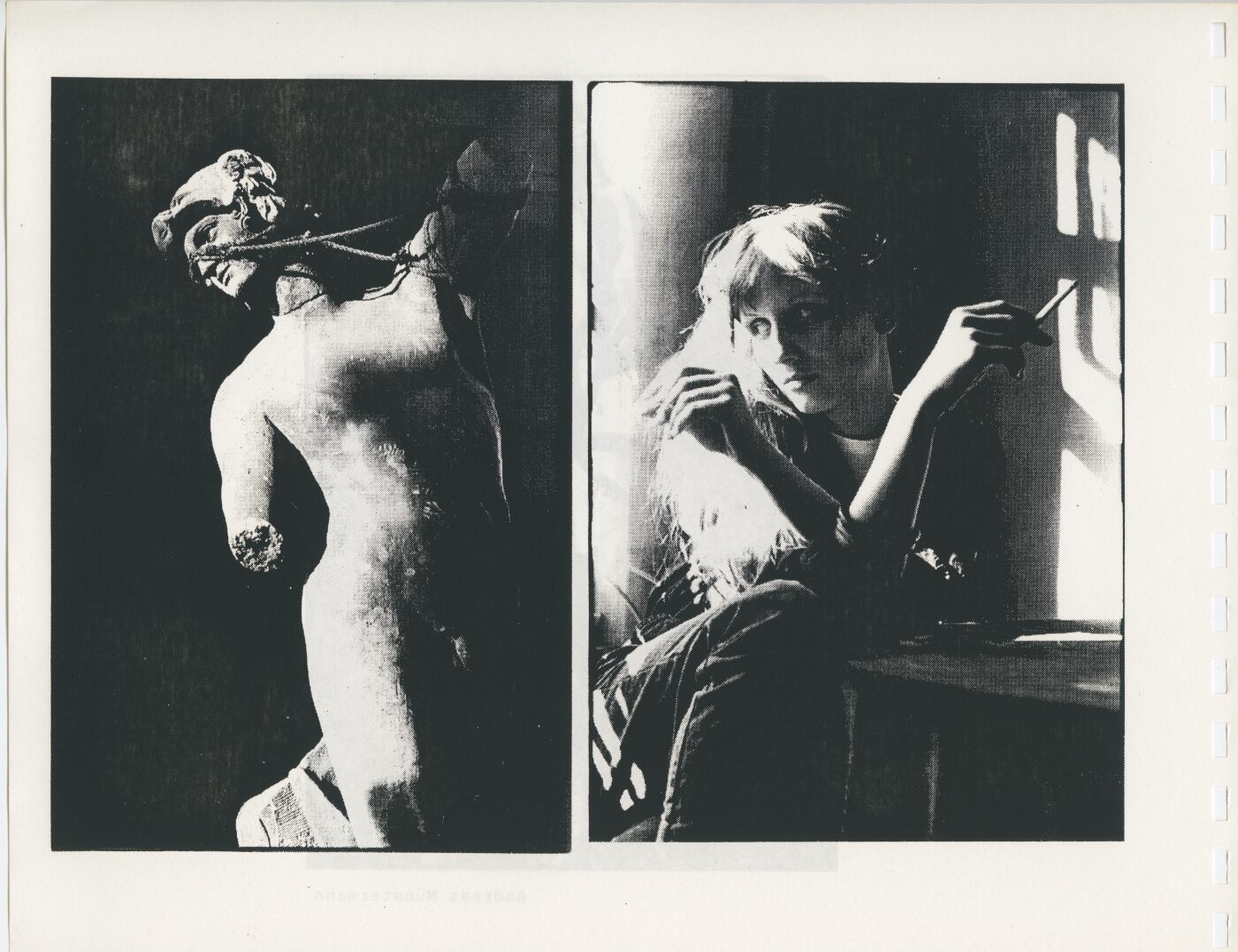

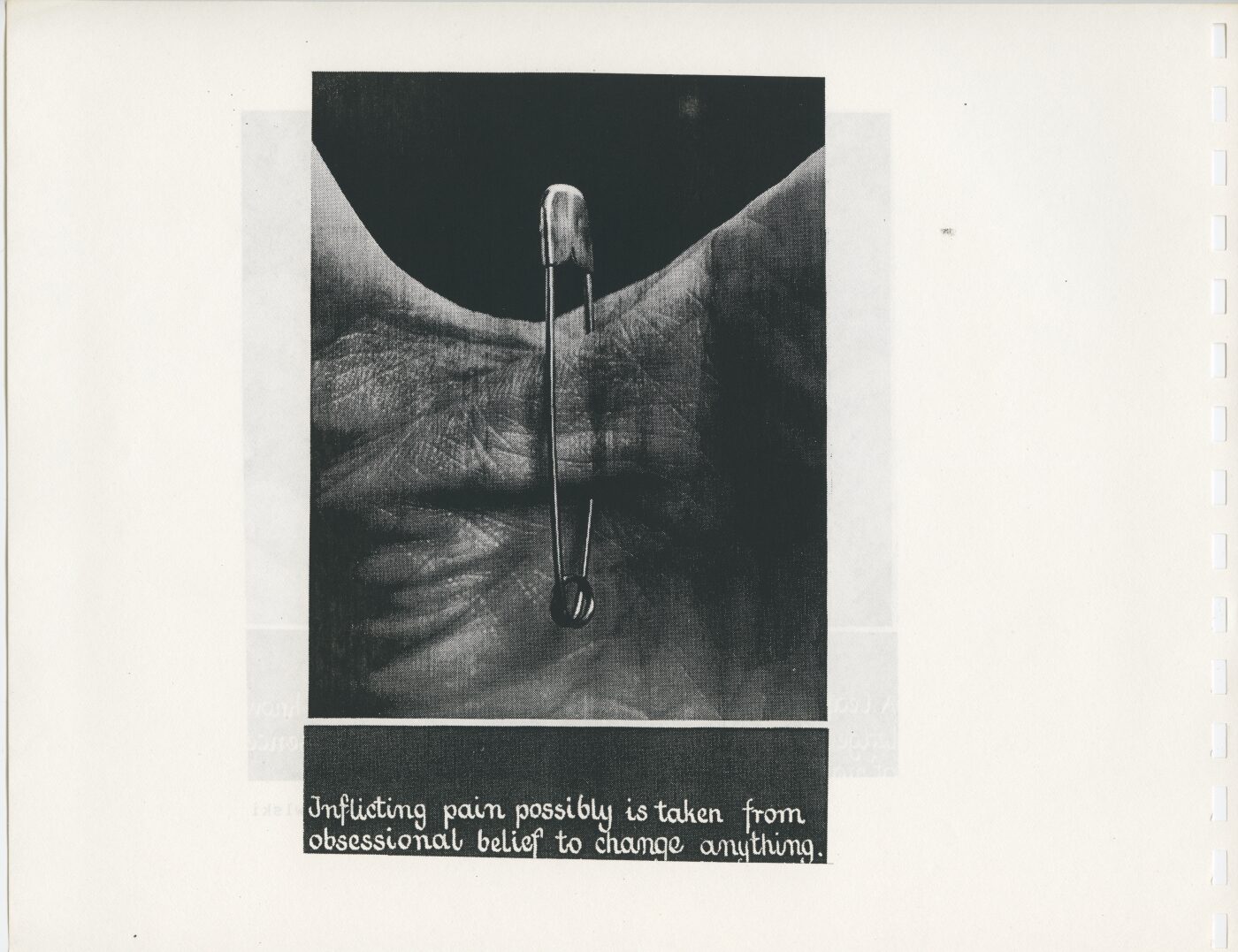

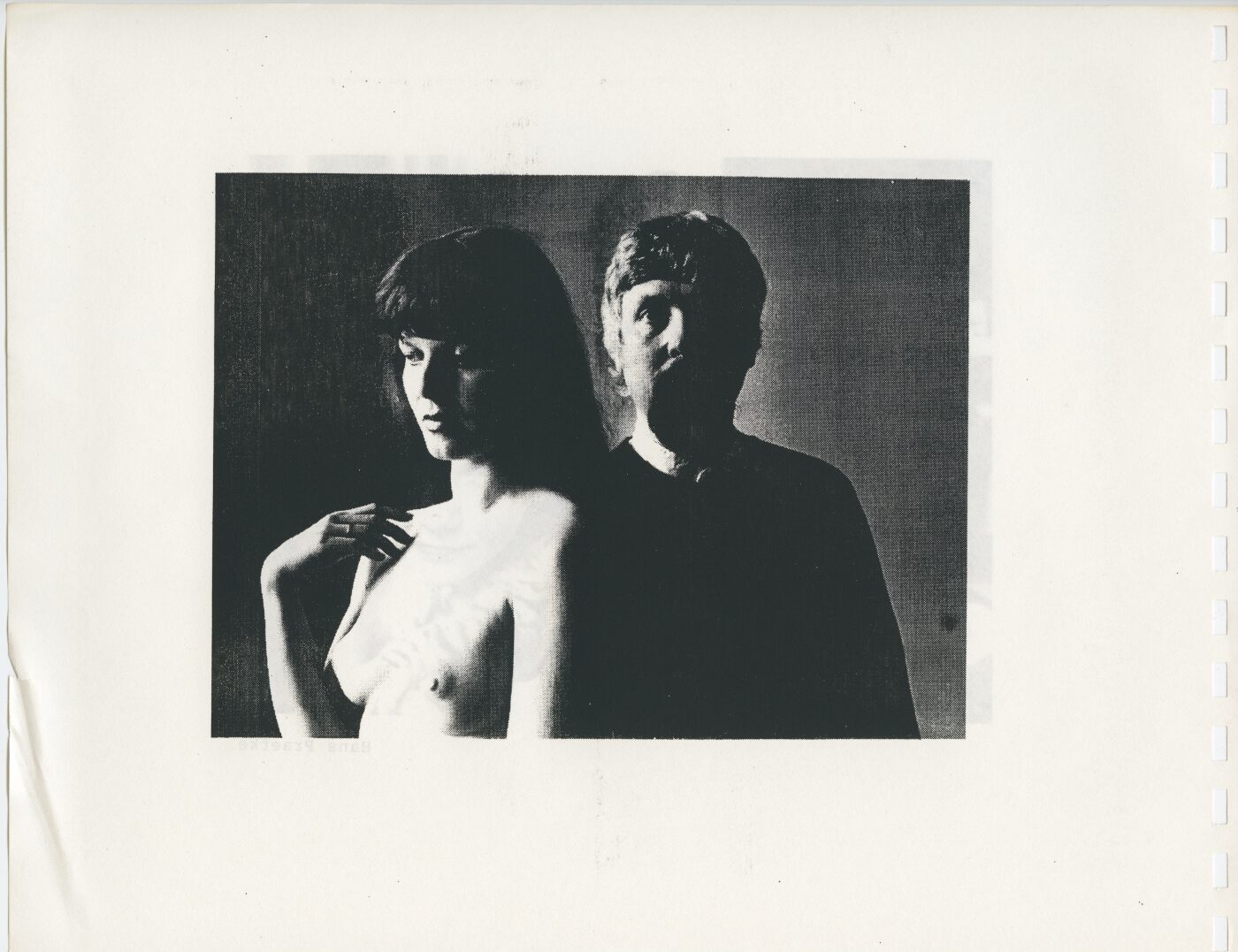

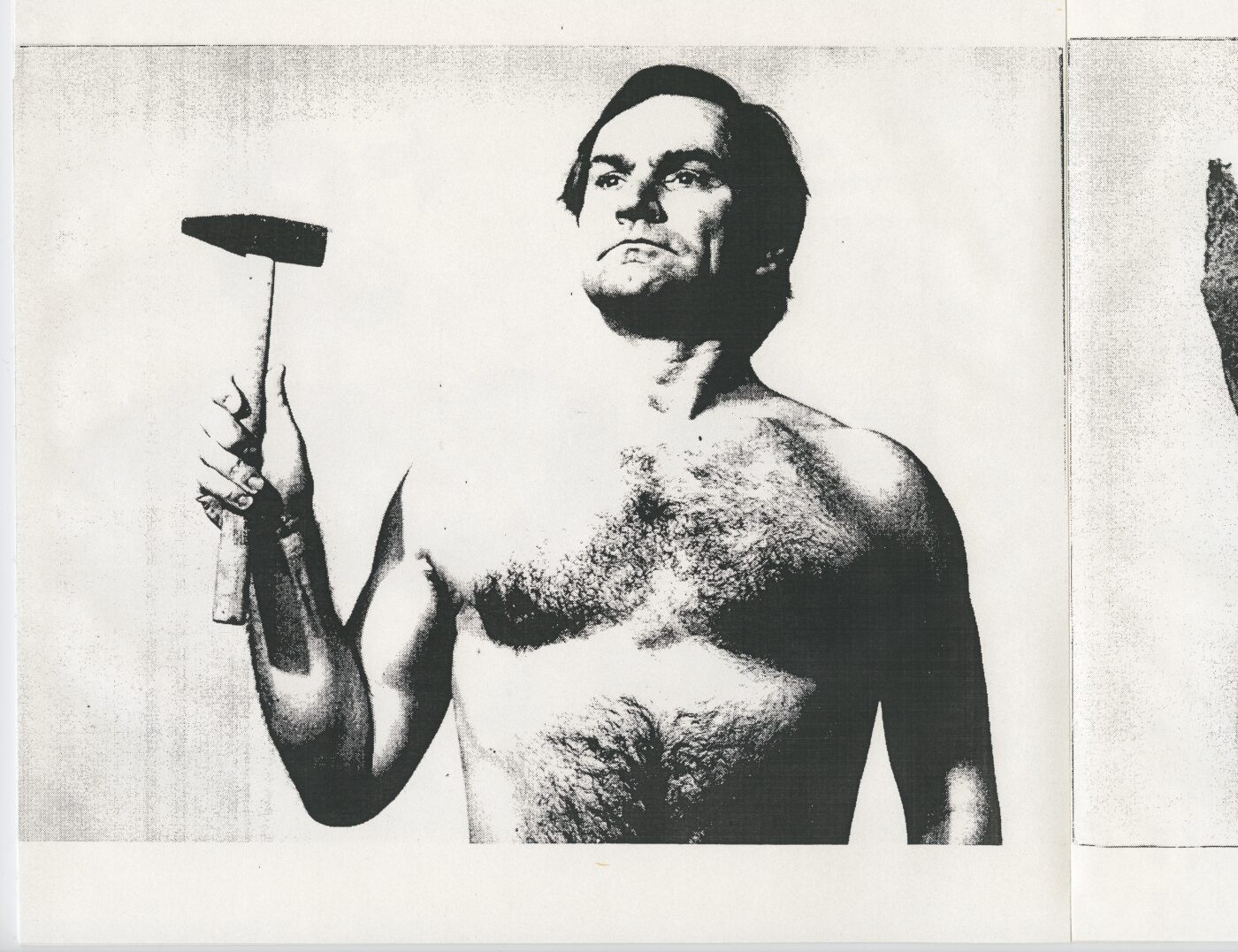

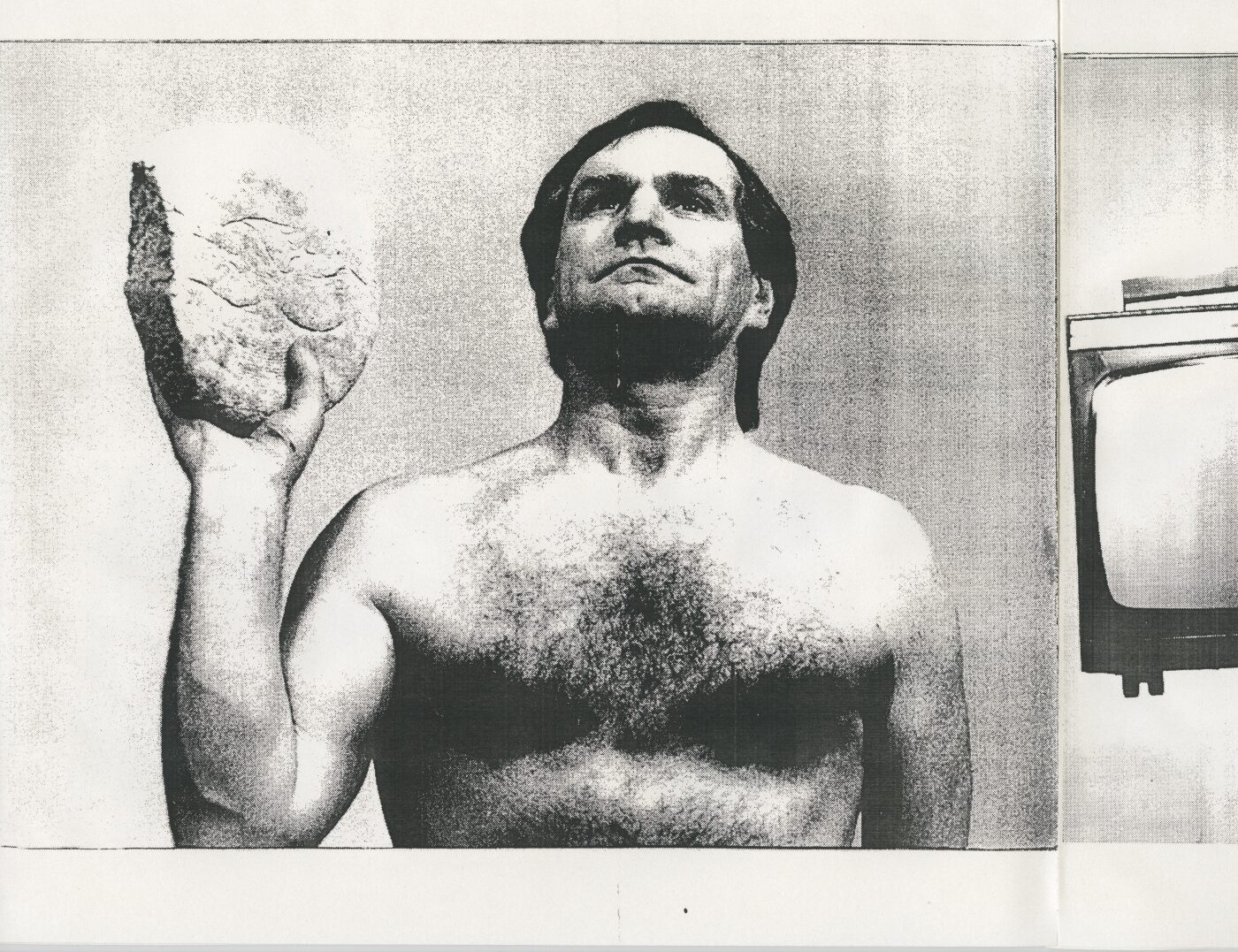

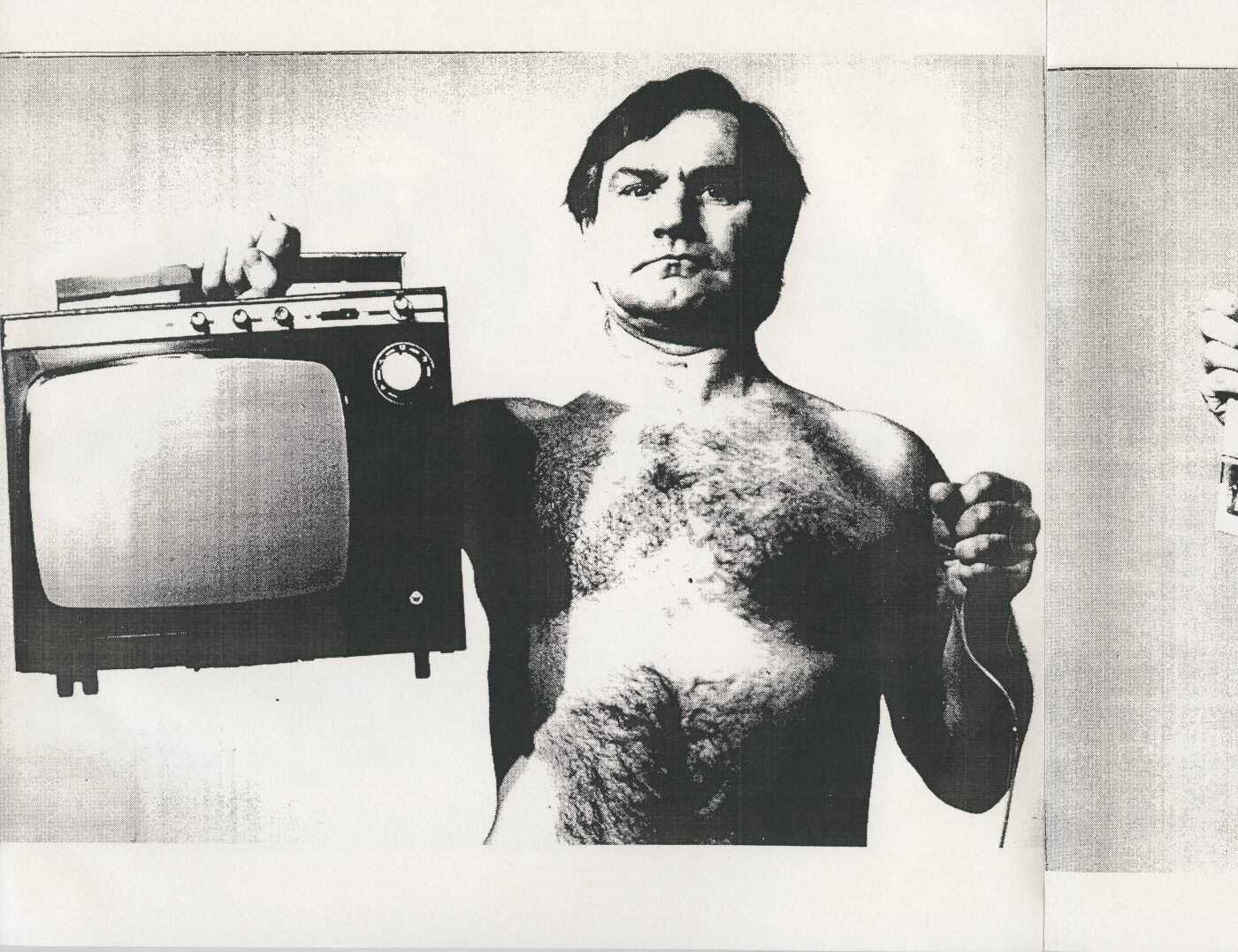

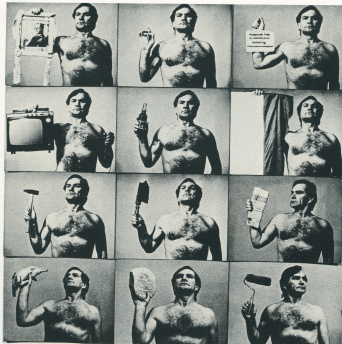

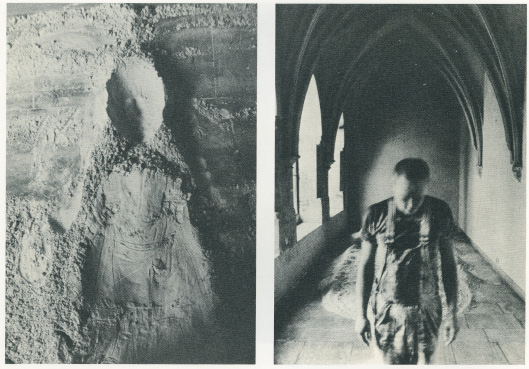

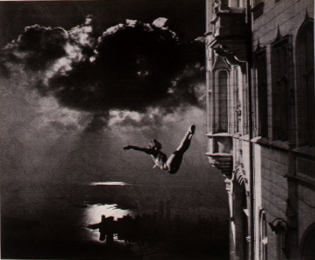

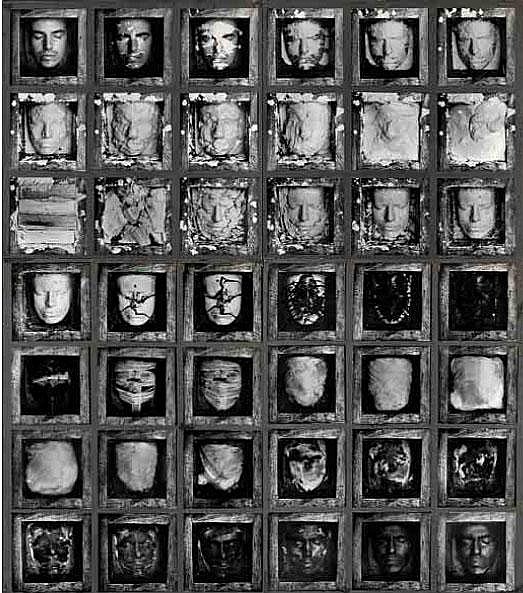

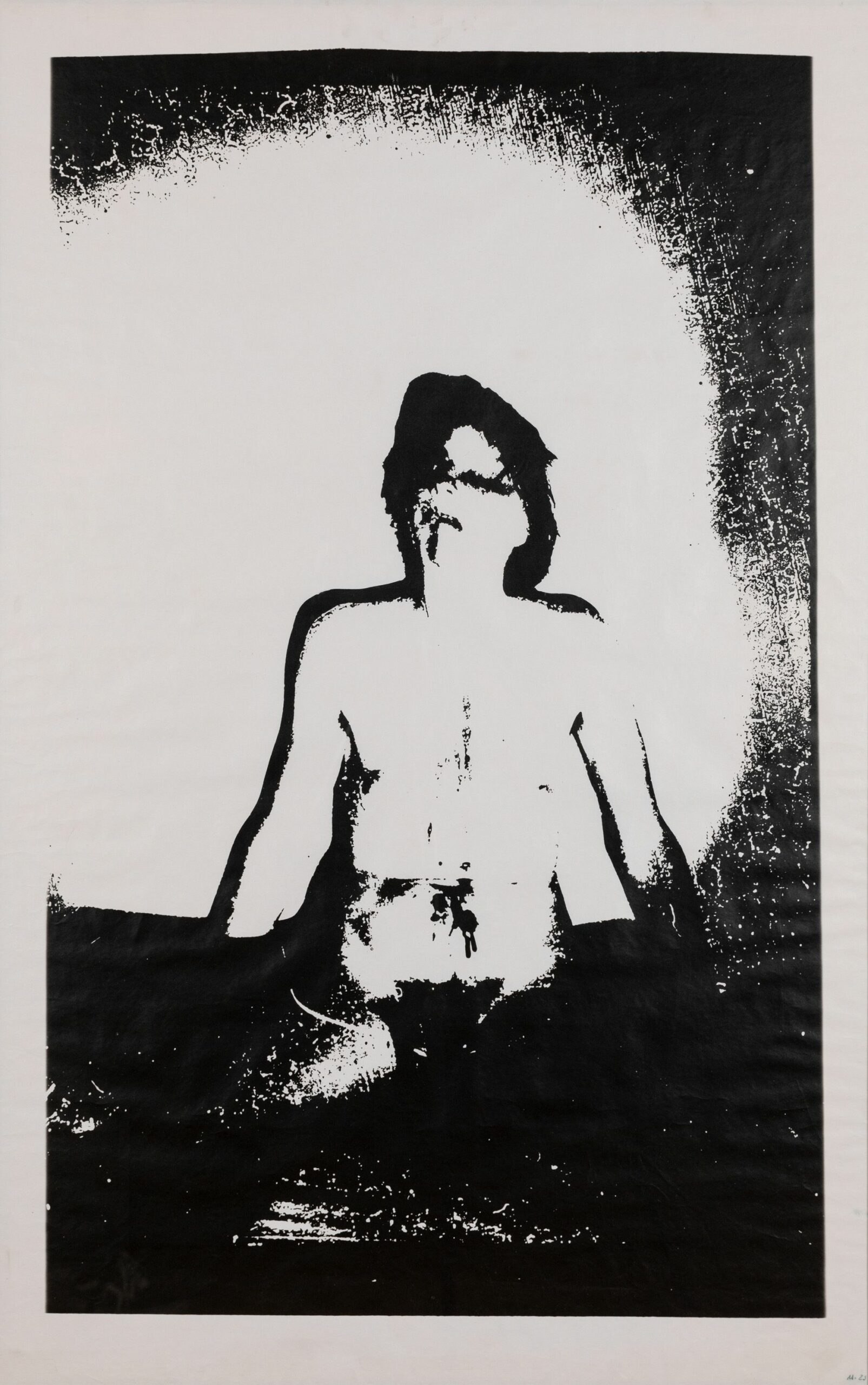

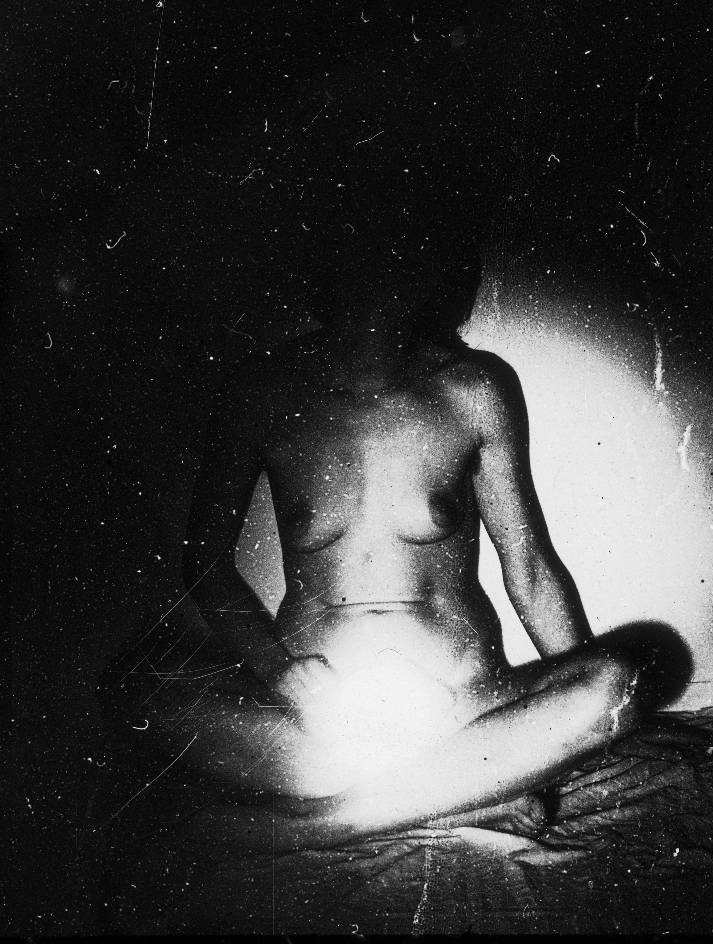

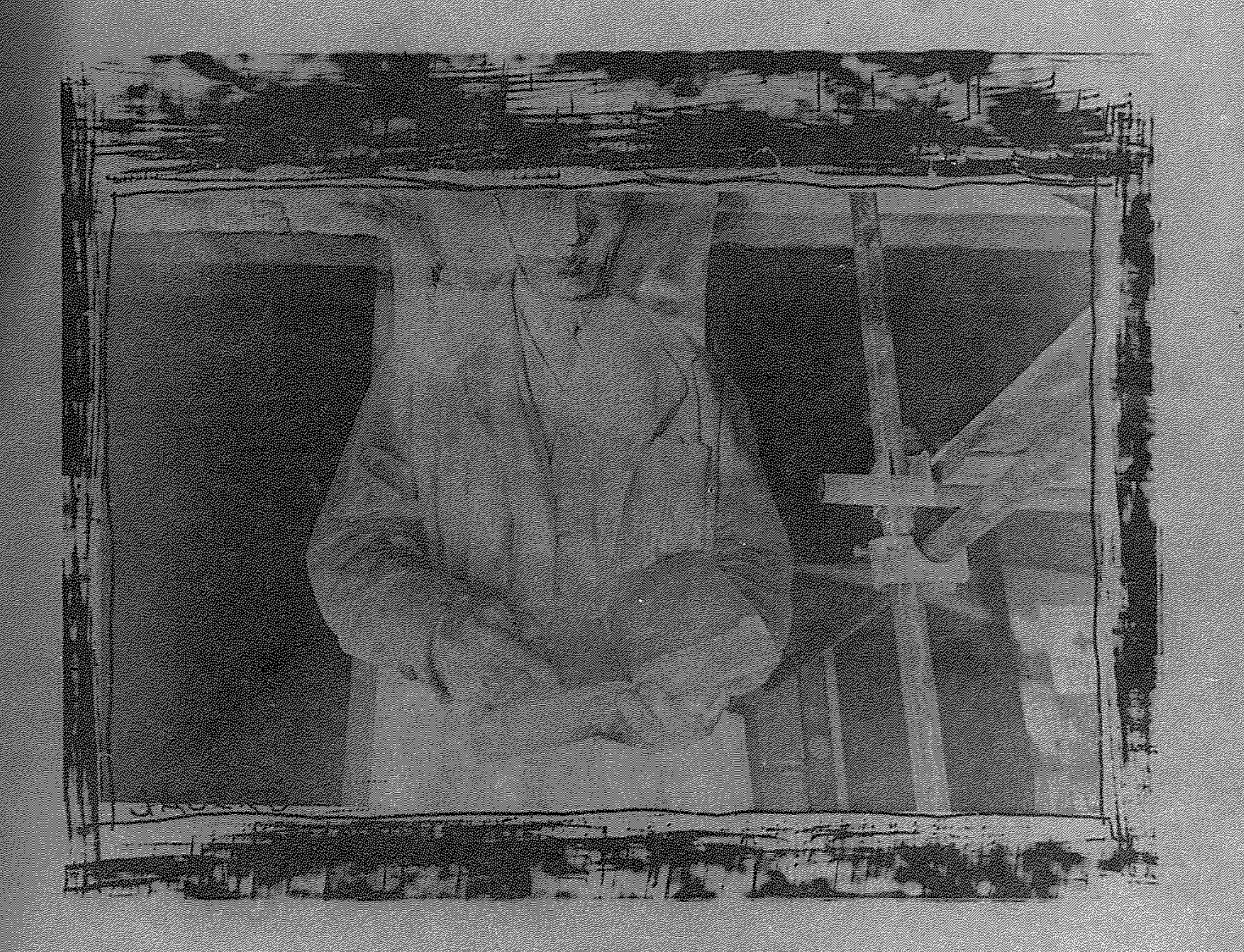

The work of Thomas Florschuetz exemplifies this apparent contradiction. Born in the German Democratic Republic in 1957, Florschuetz is a self-taught photographer who has developed a technique that is unique in the DDR. Until approximately 1986, Florschuetz used the square frame of the photographic negative to fragment his body, and the print, each containing a piece of the fragmented whole, to rejoin the parts. Occasionally he employed more or less identifiable objects, such as tea bags and film canisters, as suggestive physical extensions. The contortion of the body through an unusual placing of limbs and/or objects where none should be, as well as an almost perpetual appearance of physical pain, dominate his early images. Underscoring their power is his technique of execution, the “excessive amateur strategy” (Klaus Werner) by means of which Florschuetz sets aside the historical fetish of the fine print in favor of grey tones, grainy and dusty. Fragmentation, pain, and contortion work together with the physical flaws of the artist’s medium to establish meaning.

Many of Florschuetz’s recent photographs have abandoned simple fragmentation to explore in greater depth the relation of the body to things. For a series of installations, Florschuetz constructed large, recognizable objects from particle board, such as pieces of furniture, and joined them to his photographs. Though recognizable, the dimensionality of the objects has been severely altered by flattening. The connection of the body to the objects they join continues beyond the confines of the photographic print in these works. The small print of the misshapen body thus becomes an extension of the far larger, altered object. Through mutilation and reconnection, both body and object are removed from their traditional, cultural roles. In the process, both are robbed of meaning.

To respond to Florschuetz’s photographs as being descriptive of the hardships endured by the artist in the socialist state is to enlist their meaning to fulfill our own mythical needs, to assure ourselves that ours is a world free of such pain. This interpretation can only return us, full circle, to the imaginary cultural cemetery that the very presence of these photographs defies. To extract meaning from myth, it is necessary to reexamine the role of the artist in the contemporary socialist state.

Rigid censorship in the arts is no longer practiced in many Eastern European nations. Artists, who have long been courted by the state for greater participation in official culture, have been rewarded with this lessening of control for their acceptance of self-censorship. As increasingly influential styles of creative production, such as those originating in the West, are tried and approved by Cultural Ministers for their value to socialist culture, broader expanses of expression have opened to Eastern European artists with which they are free to work. To be of value in the socialist state, however, the art work must be constructive; its meaning must possess a value beyond that of self-reference. Self-censorship, by means of which the artist transcends his or her own interests for the good of the state and community, implies an acceptance of the specific realities of socialist culture. For the artist who participates in official culture, self-censorship means the necessity of finding the social context of his or her work such that the values of socialist culture are promulgated. Although a diversity of interpretations are now acceptable, and artists wishing to may now directly influence the look of state culture by their participation in it, the historical relationship of the Eastern European artist to the demands of Socialist Realism has not changed.

In the practice of Socialist Realism today, only one taboo remains: the acknowledgement of more than one reality, including a reality of one’s own. To recognize the existence of more than one reality is to devalue the concept of reality itself, for clearly there can be no “real” reality when more than one exists. With the devaluation of reality, the construct of history, shaped of the political and economic chain of events by which a culture is defined, is shattered. Without history, the “givens,” by means of which we recognize ourselves at home in the world, disappear. Thus, art works that construct their own reality reject the dictum of Socialist Realism that all art, if it is truly art, exists for the social good. Such art works possess no value for the community, and are prohibited for their failure to support the structures of socialism.

Thomas Florschuetz is a nonconformist, but he is not a “dissident.” His work does not conform to the demands of Socialist Realism, so he cannot be counted among the representatives of official culture. Florschuetz has studied photography independently. He has developed his unique style by working outside and, when possible, inside the academies, unions, and exhibition spaces of the DDR. Above all, Florschuetz is profoundly aware of the tug-of-war of influence from the West and the power structures on either side of the border capable of permitting or prohibiting, and thus of defining, his work. Thus, the photographs of Thomas Florschuetz do not so much contest the values of socialist reality as they stand against all oppressive forms of representation and identification that define individuals as existing to fulfill an abstract historical agenda. Florschuetz rejects not only the single-mindedness of Socialist Realism, in his denial of the validity of any reality, but also the small-mindedness of Capitalist Aesthetics, in his defiance of the saleable fine print.

The photographs of Thomas Florschuetz speak strongly because of the powerful questions they pose: What is the process of our identification in the world? If we choose not to accept the construction of our identification by external forces, how may we then know the world, which is identifiable to us only through constructions determined for us by the very forces we reject? How are we chosen for and identified through our work? What is the role of the artist in the construction of representation and identification?

Florschuetz dissects the reality of the identified (gendered, classed, politicized) self through a process of self-fragmenting and reconstruction. He dismantles his as well as our own relationship to the objects that surround us, and with which we surround ourselves, by mutilating them. By means of this process he denies their function as signposts for our self-identification. Alone in the DDR, Florschuetz’s photographs move beyond the study of the self in society to deconstruct the relationship of the individual to the world. The deconstructed world to which he brings us is one in which the universality of recognizable signs has been removed, where we must discover our own solutions, reconstruct ourselves to our own specifications, create our own reality, our own history.

Thomas Florschuetz’s photographs are not so naive as to propose that reality may be altered by the simple crossing of a border. The rejection of ideological constructions which his work proposes may be understood fully only when we accept that our own reality, our history and self-identification, our mythology as a united people, is fraught with equally virulent constructions. Florschuetz’s photographs demand we extract ourselves from mythology, East and West.

The Fragmented Universe Within Us

Christoph Tannert, Berlin, DDR, 1988

Thomas Florschuetz, traveler between worlds, moving from Germany to Germany to spur his ego, sees where the fissures of this world lead. We first perceive them between the two social systems. But the torpedoes of ideological curses come, first of all, from ourselves. Their firing devices have left their dispersed traces within us, long before we become aware of them. A key picture that reminds me of this is one he simply titles Head I; and he dates it, as usual, as a diary entry: 4.5.1985.

Florschuetz comes from Saxony, lived for a long time in East Berlin, and now, since freedom of thought did not give him enough fulfillment without freedom of action, he has moved to West Berlin.

He sees that desolation and isolation surround him, that communication in mass society is failing, and that hopes for mutual exchange and closeness are shattered. Yet his intention is not didactic or literary. When he places his body in front of the camera, he does so to inject his fever into our blood and not because he is obsessed with self-sterilization. Notice his decision against the extravagant use of staging with models in selected locations and for the simple utilization of whatever is at hand: heads, arms, legs, hands, feet, as well as whatever everyday objects are found on or under the table; also trash, leftovers from a meal, and debris from civilization. This shows him to be an artist with an eye for whatever is out of place, unnoticed, unsightly, unspectacular. Florschuetz can be compared to his friend and fellow artist Klaus Hahner-Springmuhl, an “excessive amateur strategist” who also “breaks through strict autism and, acting contrary to his contemporaries, makes his way down in his career” (Klaus Werner). Likewise, Florschuetz is not concerned with professionalism, which, with surface gloss and a fetish for neatness, kills the suggestibility of insignificant things. To be not a zoom-lens voyeur but an archaeologist in remote fields—here, perhaps, is photography’s chance to escape its role identification and the emphasis on technique. The individual photographs (50 x 50cm each), arranged in rows, a block or cross, or other configurations, strike me as a nightmare dreamer’s playground. The photographs project the power that must have been present at their creation, the emotion that Florschuetz possessed. It is certainly possible that Florschuetz executed the shot just when his venturing head (daring to go too far?) hit against the lens. Such a risk in art, as in life, is not without wounds. We see that the medium always tries to escape from the viewer’s desired view of reality. Florschuetz exploits this uncertainty that arises when one doubts the veracity of a photograph by confusing the viewer, accustomed to documentary or eyewitness account photography, with an aesthetic reminiscent of that kind of painting in which the fragmentation, the controlled cracks, and the picture’s sensuality override the motivation of content. Yet the photographs of Thomas Florschuetz also visualize something that is particularly significant in John Cage’s thinking and his “Music of Silence,” namely, unmeasured time, nonknowledge, nonsharpness, chance; in short, “anarchy where it works” (Cage), (not that Florschuetz has done an exhaustive study of Cage’s work). What stands out, however, is that calculating what is intuitive means a lot to him, whereas the subsequent processing of prints means nothing at all. While photography in the DDR, Florschuetz’s homeland, was becoming deadlocked, Florschuetz loosened the fetters of impartial object-orientation with the help of a vigorous emotion that shatters objective calculation. Florschuetz denounces “the shit of being and its language” (Artaud). For him, dependencies do not exist except for the bondage of having his own ego coerce him. With co-op projects organized in East Berlin between 1984 and 1986, some of which he organized with the painter Wolfram A. Scheffler, Florschuetz clearly expressed this claim of independence from society. Just as body parts strike the edges of his pictures in revolt, Florschuetz’s psychical disposition resists norms and shows itself the exploitation of space for making a personal decision. Formal disarrangements, whether the anatomical peculiarities of a cuttlefish or the entangled legs of a kitchen chair saving itself from functional use (nailed to the wall as a particleboard cut-out), these are the platforms for the Florschuetz difference. He stumbles up the platforms into the hall of fame but always lands back down into the disarranged sidelines of role assignments.

Since his first photographs in 1982, Florschuetz has continued to develop his style. From the very beginning he ventured beyond the boundaries of photographic organization and experience and established a new approach to reality. Whether “genial dilettantism” (Wolfgang Mueller) or a threat aimed at the photographic domain which surrounds him, his work is still characterized by long exposure and a flexible camera arm that can judge degrees of focus and nonfocus. First, there are the portraits of his friends. They register moods, perceptions, and conditions in a manner that expresses the incidental movement of the camera toward the face, as well as a hint of incompletion suggesting possible completion. His later inclusion of body parts clearly proves what motivated his early portraits: Florschuetz breaks off where unclear impulses begin to be clear. Process-oriented thought and action acquire form in complex images which, with illusion shattering impact, put our existence on a pillory. This is an existence which, fragmented in time and space, gets lost in high-security buildings, crumbling reactors, and rivers of money, searching for the certainty of life’s continuation after realizing the limitations on our grand hopes for change.

More recently, Florschuetz has been working to create contrast with the forms he discovered. Entangled bodies clash with extravagant particleboard silhouettes of chairs and tables as if to simulate interior design. Rooms exist only in the imagination. Outreached arms are empty promises. Florschuetz mobilizes our senses so that we become aware of our atrophied brains. Other works based on an image-within-an-image drive us further into uncertainty. The principle of embodiment joins that of juxtaposition. Photos of hands holding some sort of objects (bones, a photograph, a withered rose) combine with photos that show photos of hands holding some sort of objects … Florschuetz disorients us, making us doubt the reality of the photographic reality. What is inside? What is outside? Beyond the prints of the prints is there perhaps no reality, no world? Has Florschuetz discovered Hegel or Lyotard or… ? A dash of philosophy taken from the stocked supply of forms of a spontaneous artist interested in the overemphasis of form spikes his works with an even more potent dose of selfassurance. First the primitive images of a man trembling with palsy who splits open his heart; then, a catharsis. After the display there is registration in a state of new sublimity.

Translated from the German by Mil Norman-Risch.

Thomas Florscheutz (Open/Download PDF)

September 1 – October 17, 1988

Anderson Gallery, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA

JP Jacob

Thomas Florscheutz: Extracting Meaning from Myth

JP Jacob is an artist and independent curator who works extensively with artists in Eastern Europe.

Christoph Tannert

The Fragmented Universe Within Us

Christoph Tannert is a writer and critic who lives in East Berlin. He has written several essays on Thomas Florschuetz.

Th. Florscheutz Bio

Born in Zwickau, East Germany (DDR), 1957

Lives and works in Berlin

1987 First prize for Young European Photographers in Frankfort am Main

1988 Stipend from the Senators for Cultural Affairs in Berlin

Solo Exhibitions

1983 Jugendclub W.-Pieck-Strasse, Berlin (East)

1984 Privat-Galerie (with Wolfgang Scheffler), Berlin (East)

1985 Galerie Herrmannstrasse, Karl-Marx-Stadt, DDR

1987 Atelier V. Henze, Berlin (East)

Museum Folkwang, Essen, BRD

Rencontres D’Arles ’87, Arles, France

Galerie Neue Raume, Berlin (West)

Mary Porter Gallery, Santa Cruz, California

1988 Galerie du jour agnes b., Paris, France (cat)

Anderson Gallery, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia (cat)

Group Exhibitions

1984 Kunstler fotografieren—Fotografierte Kunstler, Galerie Mitte, Dresden; Galerie

Oben, Karl-Marx-Stadt, DDR (cat)

1985 Junge Fotografen der achtziger Jahre, Galerie Mitte, Dresden; Galerie Oben, Karl-Marx-Stadt, DDR (cat)

1986 Der Hang zum Pathos, Stollwerckumenta, Koln, BRD (cat)

1987 Junge europaische Fotografen, Frankfurter Kunstverein, Frankfurt am Main, BRD

Out of Eastern Europe: Private Photography, List Visual Arts Center, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts (cat)

1988 Figur & Zeichen, Staatliche Museen Cottbus, Cottbus, DDR (cat)

Young European Photographers, Houston Foto-Fest ’88, Houston, Texas

entgrenzungen, Hahnentorburg, Koln, BRD (cat)

Bibliography

DDR FOTO. Edited by W. Koenig and G. Adler, Berlin (West), 1986.

Tiefe Blicke—kunst der achtziger Jahre aus der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, der DDR, Osterreich und der Schweiz. Koln, 1985.

Thomas, Karin. Nahe und Feme—Zweimal deutsche kunst nach 1945. Koln, 1985.

Thomas, Karin. “Korperbilder,” European Photography 32 (October/November/December 1987): 16-17.

“Young European Photographers ’87,” European Photography 33 (January/February/March 1988): 18, 40-41.

Portfolios

Thomas Florschuetz. Edition Karin Thomas, Koln, 1985. Series of six photographs with story by Stefan Doring. Edition of 30.

zweite sekunde eines schrittes. Berlin (East), 1987. Series of 17 photographs and text by Christoph Tannert. Edition of 11.

Czechoslovakia

Milan Knizák

USSR

Jacob travelled to the Soviet Union the first time in 1986, during his second visit to Europe of that year (his first trip to work on Out of Eastern Europe: Private Photography). He traveled with a tourist visa and visited Moscow, where he stayed at the historic Hotel National on Red Square, and Leningrad. Jacob and Katy Kline, new as director of the List Visual Arts Center (LVAC) at MIT, agreed that, depending on what Jacob found there, he might guest-curate a subsequent exhibition, following Out of Eastern Europe.

In Moscow, Jacob travelled with a contact list given by Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin. His primary contact there was Igor Makarevich, a conceptual artist and member of the Collective Actions group who was active in Moscow’s underground art scene since the 1970s. Makarevich was a contributor to Second Portfolio exhibition in Budapest (along with the Gerlovins and Vagrich Bakhchanyan). He introduced Jacob to other members of the Collective Actions group, and also connected Jacob with Alexey Shulgin, whose English language skills made him central to Jacob’s work with Soviet artists. Jacob was less successful in Leningrad. During his week there he mostly walked and visited museums.

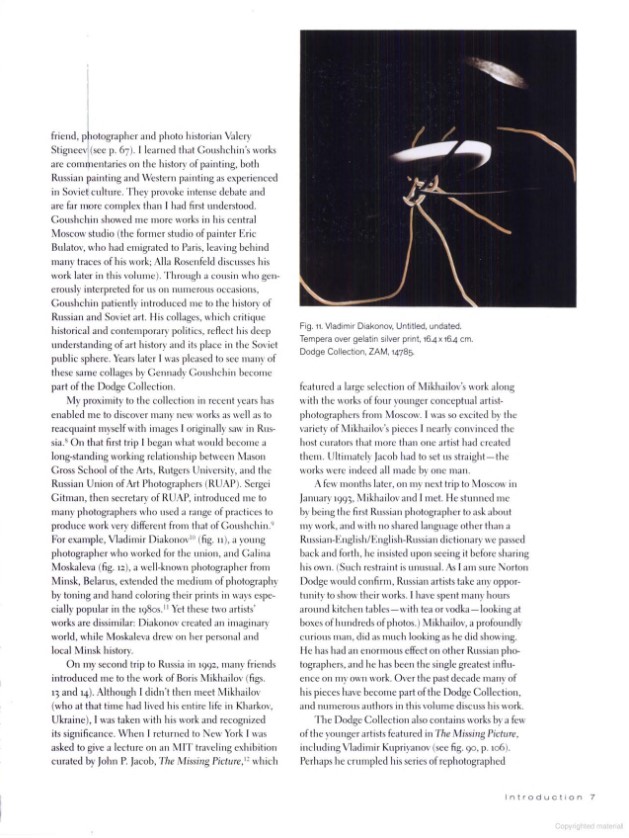

Jacob initially planned to organize a large survey exhibition of Soviet photography for the LVAC, mirroring his work on Out of Eastern Europe. That plan was scrapped, due in part to the vast geographic scale of the USSR and the difficulty of traveling there for a foreigner. More importantly, Jacob came to identify a small, Moscow-based circle of photographers influenced by the Ukrainian photographer Boris Michailov as a strain of Moscow Conceptualism. When The Missing Picture: Alternative Contemporary Photography from the Soviet Union opened at MIT in 1990, it offered a one-person exhibition of works by Michailov and a separate group exhibition of works by four young Soviet photographers inspired by him, Vladimir Kupreanov, Ilya Piganov, Maria Serebrjakova, and Shulgin.

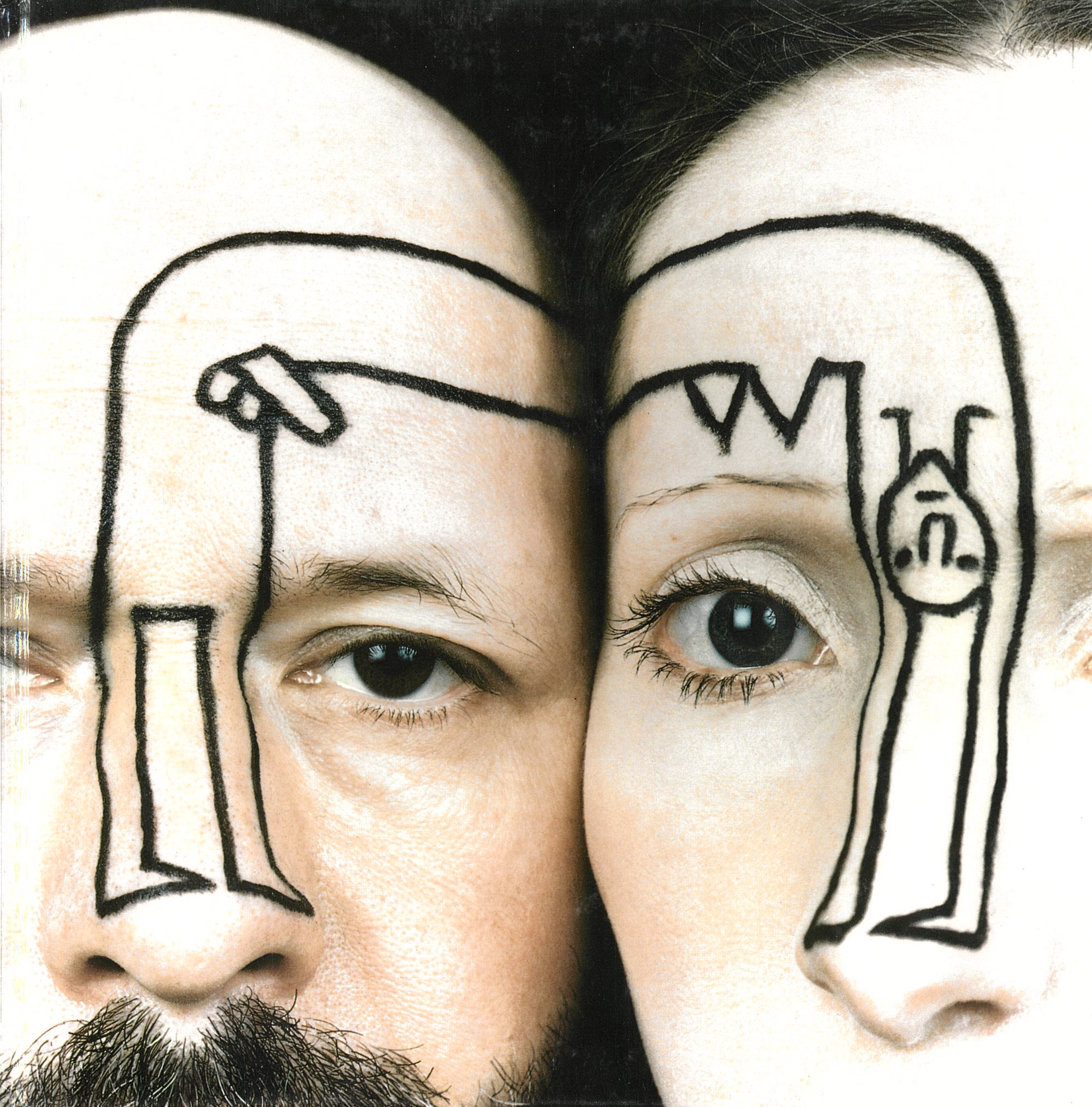

Metamorphic Game: The Art of Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin

John P. Jacob, Austin, TX, 1989

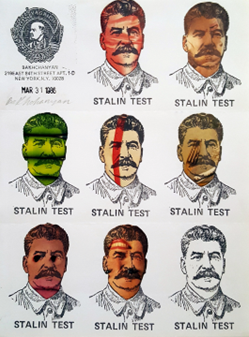

The Moscow School of artists, from which Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin emerged in the late 1960s, originated in the trauma of de-Stalinization. In 1956, in a secret session at the 20th Party Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Khrushchev denounced the memory of Stalin, detailing his crimes against the Soviet State. Khrushchev’s attack on the former leader, and on the way of life that the period of his leadership had come to signify, had a profound and irreversible effect. In the years that followed, the Soviet Union experienced a liberalization of power that, in the field of the arts, came to be recognized as a cultural revolution. The “thaw,” as it came to be known, lasted into the early years of the Brezhnev regime. In 1968, as Soviet troops entered Czechoslovakia, crackdowns on the arts and culture resumed.1Portions of this text were adapted from an earlier essay “Photems, or: A History of the World in Five Parts,” CEPA Quarterly, Winter/Spring 1988, pp. 18-21.

Many young artists working in the early years of the thaw (1950s) sought to expand their education and practice beyond the stylistic offerings of the official Moscow Art Institute. They were among the first generation to learn of (though not necessarily to see) the long suppressed work of the early 20th century Russian avant-garde, and to feel the influence of Post-Impressionism and Surrealism. Vilified by Khrushchev and later suppressed by Brezhnev, Soviet artists continued to work in experimental styles despite official disapproval.2Gerlovina, Rimma and Gerlovin, Valeriy, “Samizdat Art,” Russian Samizdat Art, Charles Doria, ed. New York, Willis, Locker & Owens, 1986, p. 70.

By the late 1960s there had emerged from the Moscow School a loosely associated network of artists whose shared concern was the use and effects of language.3Gerlovina, Rimma and Gerlovin, Valeriy, “Samizdat Art,” Russian Samizdat Art, Charles Doria, ed. New York, Willis, Locker & Owens, 1986, p. 70. Recognizing language as the cornerstone in the social construction of reality, these artists sought to reveal the many functions — social, spiritual, and institutional — to which language has been harnessed. The linguistic experiments of artists working in this period, like those of artists working in pre-revolutionary Russia, were deeply rooted in social upheaval. Although they shared a common socioeconomic context for their experimentation, however, it is clear now that the artists working in the 1960s and 1970s formed distinct (if at times overlapping) groups, and that they worked toward radically different ends.

Central to the activity of artists experimenting with linguistic constructions in the thaw period was the proliferation of self-published materials. Though self-publishing had disappeared from the Soviet Union in the 1930s, it quickly returned following Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin in the form of memoirs of the victims of Stalin’s purges, and in numerous manuscripts of formerly suppressed literature and poetry.4Medvedev, Roy, op. cit., p. 214. The term samizdat, which has come to encompass the varieties of Soviet self-publishing activity, was coined in the late 1950s by the poet Nikolai Glaskov, and is an ironic adaptation of the term Gosizdat, meaning State publishing.

Two distinct variants of self-publishing, political and artistic, emerged in the thaw period. Political samizdat consisted largely of critical texts by authors whose writings, for political reasons, were banned. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago is a good example of a repressed political text available only in samizdat editions. Artistic samizdat, on the other hand, aimed at reflecting the problems and values of the creative community. Most artistic samizdat was apolitical; it addressed private rather than institutional concerns. “In the social and cultural climate of contemporary Russia, literary and artistic samizdat nonetheless took on a political flavor by virtue of its unofficial status and nonconformist position.”5Gerlovina, Rimma and Gedovin, Valeriy, op. cit., p. 69.

It is as emerging from the linguistic experiments of the period, and rooted in their activities with artistic samizdat, that the works of Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin may be traced. Through the artistic samizdat activity of the 1960s and 1970s the experiments of diverse artists may be examined as a unified whole. All were participants, either as readers or writers; many as both.6The Gerlovins’ Russian Samizdat Art brings to light the full extent of the Samizdat phenomenon. What distinguishes the work of Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin is their use of artistic samizdat as a cultural and aesthetic strategy extending well beyond the book form. Originating in the artists’ recognition that the meaning of any text is completed only through the participation of a reader, this strategy is effectively carried through to the Gerlovins’ work in all other media. By the early 1970s the Gerlovins had exploded the aesthetic of artistic samizdat by transforming whole rooms into interactive textual environments.

The Gerlovin’s early work together forms two interrelated uses of the book as an artistic medium. In the first, books were created as documentation of performances, collaborations, or actions. In the second, books provided the foundation for the creation of unique textual objects and environments. In either case, the book depended upon the collaborative participation of others. Documentation, while appearing to form a fixed text, depended initially upon the interaction of the performers and the photographer (documentor), and later upon the readers to whom it gradually circulated. Meaning was not considered as fixed in such texts, but rather as an open-ended process in which the book functioned simultaneously as a document of the artists’ experiments and guide for the reader. A good example is the series Trees, or How to Photograph Dreams, 1977, which the Gerlovins made using photographs by Igor Makarevich. In this conceptual series the viewer is instructed through diagrams, text, and photographic documentation how one or more persons may select and embody themselves within a dream image which, upon waking, may be recorded by a photographer.

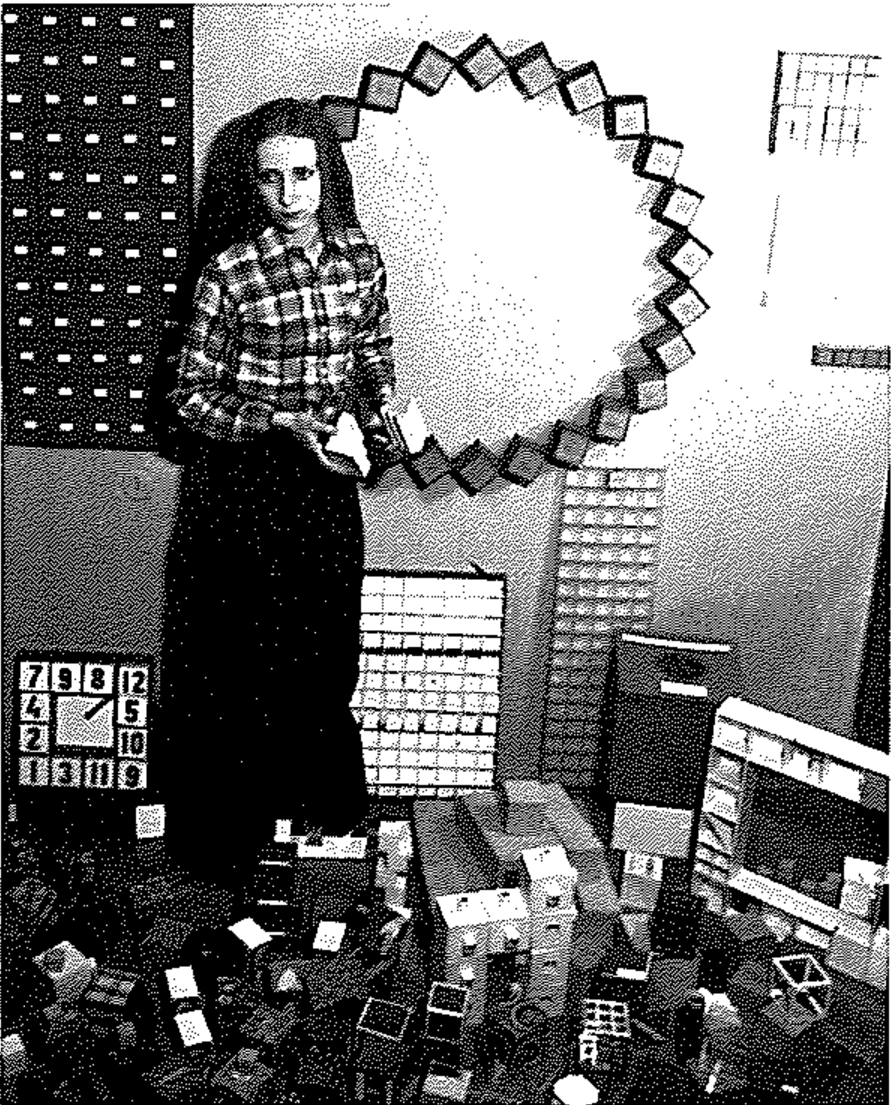

The construction of unique and one-of-a-kind textual objects and environments was the Gerlovins’ most influential work in the Soviet Union, and it was in such early conceptual projects that many themes common to their later work were developed. In the construction of conceptual texts, originating in Rimma’s series of cubic poems of 1973, the book format is transcended altogether. Among the earliest of the cubic poems was A Depraved Element, 1974, an eight centimeter square white cardboard cube containing a smaller, red cube with the words “a depraved element” typed on all sides. The white cube represented a unit of perfect form; the red cube a cell in its overall structure. When the smaller cube was removed from the larger, however, the unity of the whole was destroyed. Thus, just as the depraved element was necessary to complete the perfect form, it simultaneously depicted the element of potential error present in all concepts of perfection.

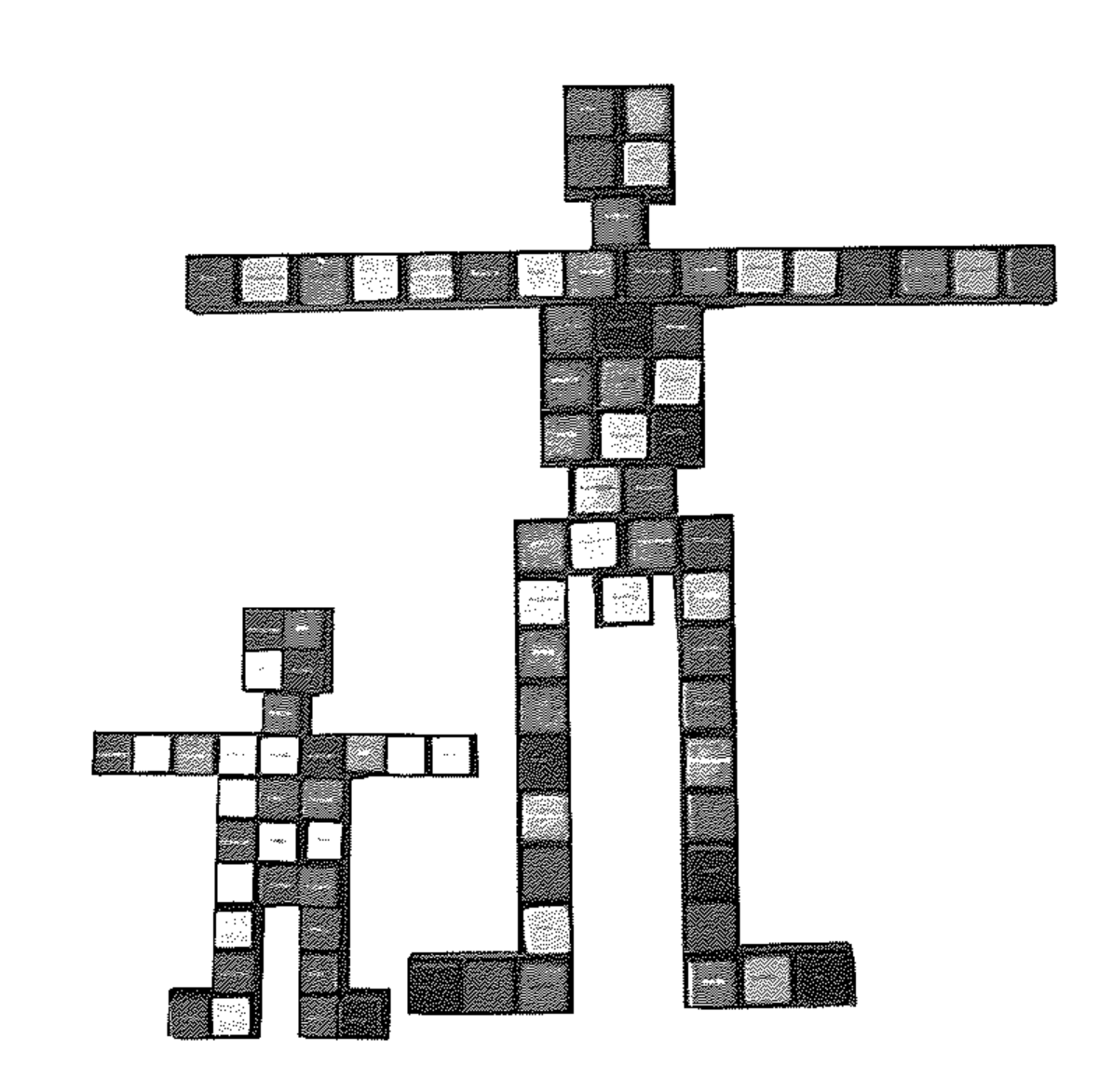

The cubic poems evolved from individual cubes to figurative and environmental cubes. Each cube represented a single cell within a larger structure. Each opened and unfolded to tell its own story through an ambiguous dialogue between inside and outside. “You think,” reads the outside of the cube; “But I am,” reads the inside. “There is a sphere inside me,” reads the outside of another; “He’s a sphere, I’m a cube,” reads its inside. Just as each cube represented a complete unit of time and space, however, each was also contained within a larger form which, by extension, was further contained within the larger universe. Each unit from the individual cube to the universe in which it existed as a single cell, depended upon the totality of all other units, and on the dialogue established among them, for perfection.

The extension of the cube from the private universe of the individual to the larger universe was manifested in a series of environmental constructions titled Spaces, 1975-76, which often incorporated elaborate performances. Viewers entering into the cubic Spaces became participants in the installation and action, and integrated elements within a complex whole. One such environmental cube transformed a single room by dividing a wall into three sections marked “Paradise,” “Purgatory,” and “Hell.” A grid of small cubes was constructed in each section, and each cube contained the name of a historical personality, such as Galileo, Jeanne D’Arc, The Beatles, etc. Visitors to the room moved the cubes randomly from one section to another, in some cases re-writing history and in others predicting the future. Through their participation, viewers grappled with the moral decision of whom should go to heaven and whom to hell, and why. The constructed environment suggested that the actions and judgments of individuals do not occur in isolation, but possess profound influence for the larger universe of which one is but a part.

The series Cubic Organisms, begun in Moscow in 1975 and completed in New York in 1982, was constructed in the figures of living forms. “A two-meter-high man made of cubes with inscriptions covering single concepts (from genius to lack of talent, or from saint to devil, and so on) is formed by the viewer himself, who at that moment is, in a sense, writing his own random poetry. This series also includes a ‘Calendar of 100 Years’ in the form of a dog sphinx, which the viewer uses to predict the future by means of movable cubes… In her cubes poems, Rimma developed her theory of ‘Transfism’ with the following theses:

1. Interchangeability (of time, space, sex, etc., as a basic principle of life and the unity of opposites)

2. Co-creativity and Pluralism (of the spectator, who completes the idea, changing the elements in the frames of the author’s form)

3. Metamorphic game (as a symbolic modeling of the world, as an a priori part of human nature)

4. Archetypal units (cubes together make a perfect unity)”7Ibid., p. 165.

It is through the collective and participatory aspects of the Gerlovins’ early work that Rimma arrived at her theory of “Transfism.” And it is through the development of the three theses of “Transfism” — Interchangeability, Co-creativity and Pluralism, and Metamorphic Game — that the recent work of Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin has emerged.

Fundamental to “Transfism” is the idea of oppositional unity; for every force there exists a counterbalancing oppositional force. Thus, in Rimma’s cubic poems the concept of angel is always balanced by the concept of devil, and so forth. In Valeriy’s early sculptural works the co-existence of the natural with the artificial was expressed through the construction of objects using mechanical elements (such as the metal pieces contained in children’s “erector sets”), and organic substances (notably brown bread). One such mechanical structure, Party Meeting, 1974, now sits provocatively in a window of the Museum of the Berlin Wall, overlooking Checkpoint Charlie. Many of Valeriy’s mechanical sculptures from this period, such as Spermatazoid, 1974, and Leaf, 1974, brought organic concepts together with mechanical materials. These sculptures were often welded to the tops of music stands. His project Bread Insects Community, 1976, combined such media to form a colony of mythological bugs molded from brown bread to create “a mystification of the life of organisms.”8Ibid., p. 168.

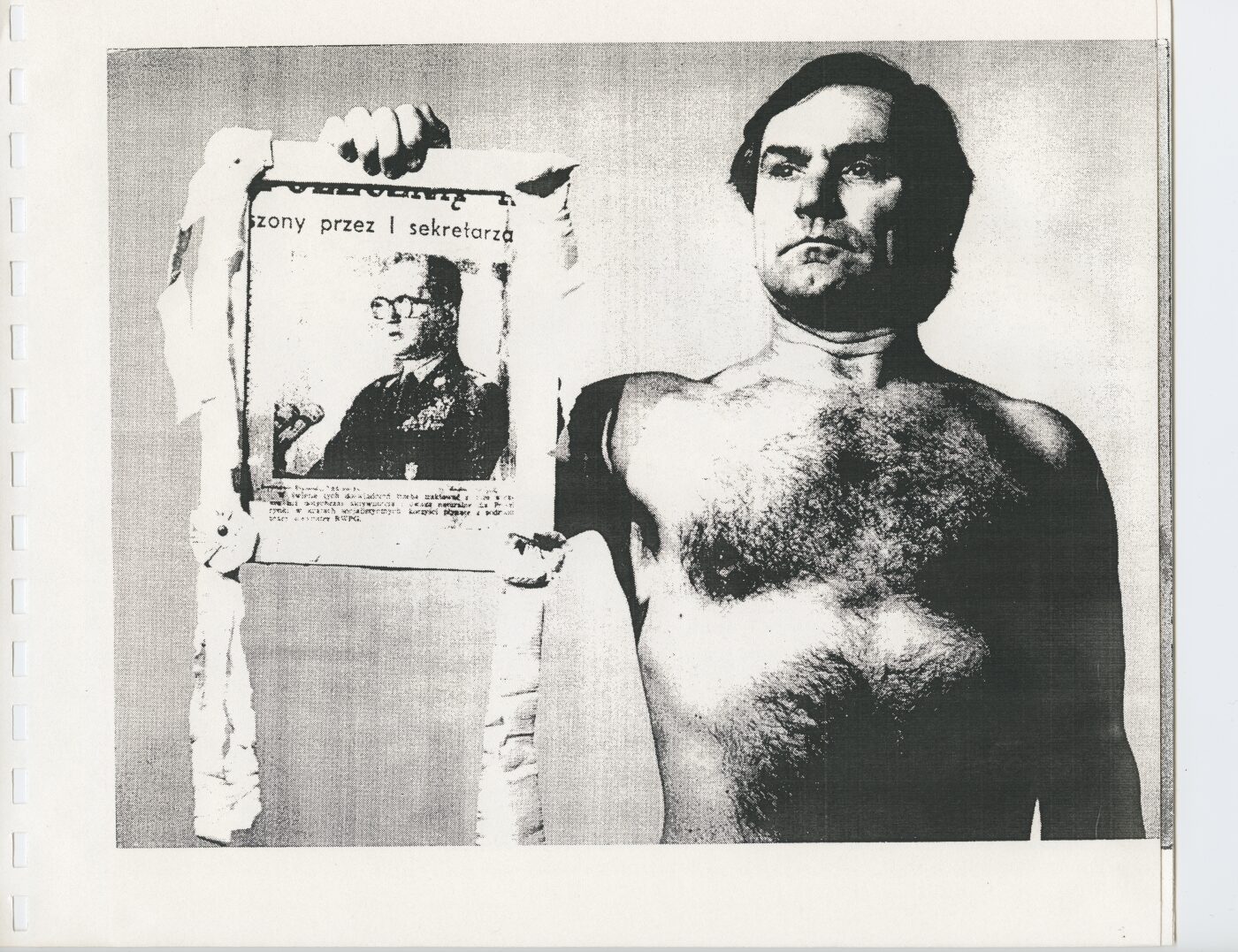

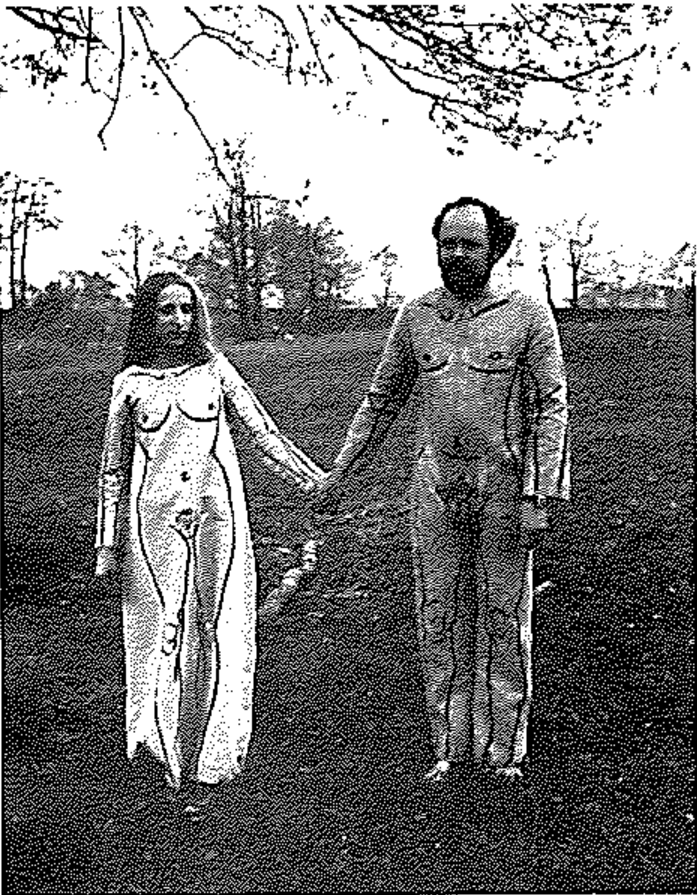

Oppositional unity is critically expressed in Mirror Game, 1977, a book documenting the Gerlovins’ performances in Moscow. Originally constructed in Moscow and later re-constructed using the original photographs in the United States, Mirror Game is composed of a series of photographs pasted to pages of a Soviet newspaper printed in the USA. As the book is opened, the individual photographs facing each other on each page present conceptual oppositions. For example, in one pair of photographs Valeriy stands half naked in trousers and Rimma wears a fur coat and hat. In the first photograph the landscape is covered with snow; in the second it is summer, and trees are in full bloom. They stand in exactly the same places, in the same attire, in both photographs. Implicit in the opposition is a game of time.

Another page of Mirror Game opens to show two shots of Valeriy, once again only in trousers. On the left page the abbreviation “CCCP” is written across his body. On the right page Valeriy’s body reads “USA.” This seemingly simple opposition extends to the actual construction of the book. The newspaper represents the official logic, thinking, and historical record of the Soviet citizen. The photographs pasted to each page of the newspaper in Mirror Game represent a conceptually opposite logic, thinking, and historical record. Mirror Game is also one of the artists’ first uses of their bodies as subject and object, a practice to which they returned ten years later.

Equally critical to the Gerlovins’ work is the pursuit of intellectual and spiritual development. This concern is exemplified in Valeriy’s Ages, 1975, a one-meter square metal book welded to a music stand and divided into four parts or chapters. The first part, marked “0 Age – 15 Age,” is an empty space. The second, marked “15 Age – 35 Age,” contains a transparent sheet of glass. The third, marked “35 Age – 60 Age,” contains a sheet of translucent glass. The fourth, marked “60 Age – 0 Age,” contains a mirror. Ages depicts the gradual transition of the self from invisible to transparent to translucent to reflective, and suggests that in the eventual return of “0 Age” the self becomes invisible once again as another stage of development is begun. In Ages, it is the self which passes, not time.

Central to the Gerlovins’ work is the development of linguistic and numerological systems. These systems are at once scientific and mystical, serious and playful. Their play with words and numbers also encompasses a profound awareness of their use in the construction and maintenance of ideological values in contemporary cultures. Quite different from artists who incorporate elements from semiotic theory into their work, however, they regard their linguistic and numerological systems as the source and substance of spiritual transformation. Words and numbers combine to form the key to their metamorphic games through which the spiritual consciousness is developed. Where semiotics offers viewers a glimpse of how language defines and systematizes the real world, metamorphic games propose participation in the universal.

For as long as man has been capable of speaking, the naming of things has been the primary structure used for ordering the environment. By means of language the objects of the natural world are identified for their use-value within a given culture. The natural is thus transformed into the cultural, and the world becomes recognizable within an ordered system of relationships that is perceived as “real.” Through language we come to identify reality.