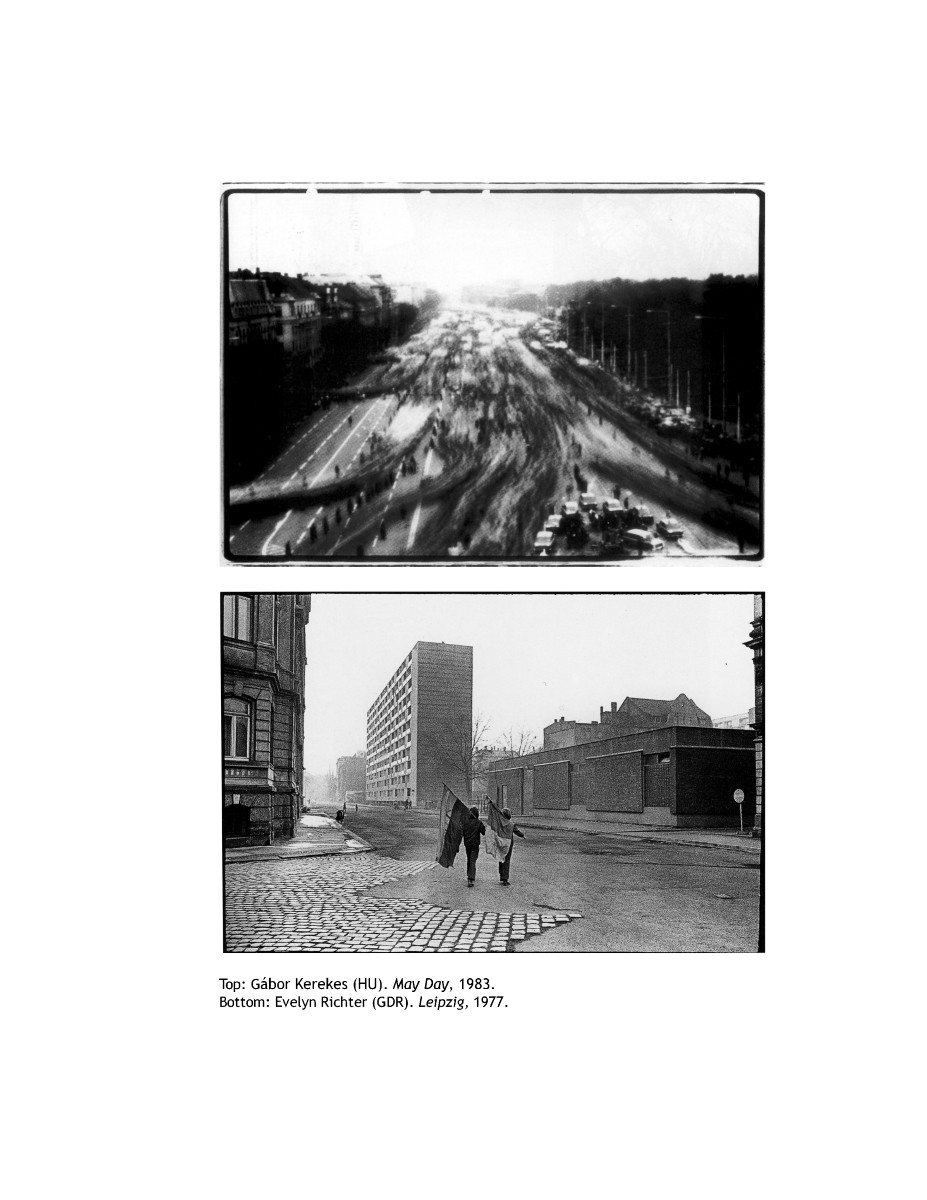

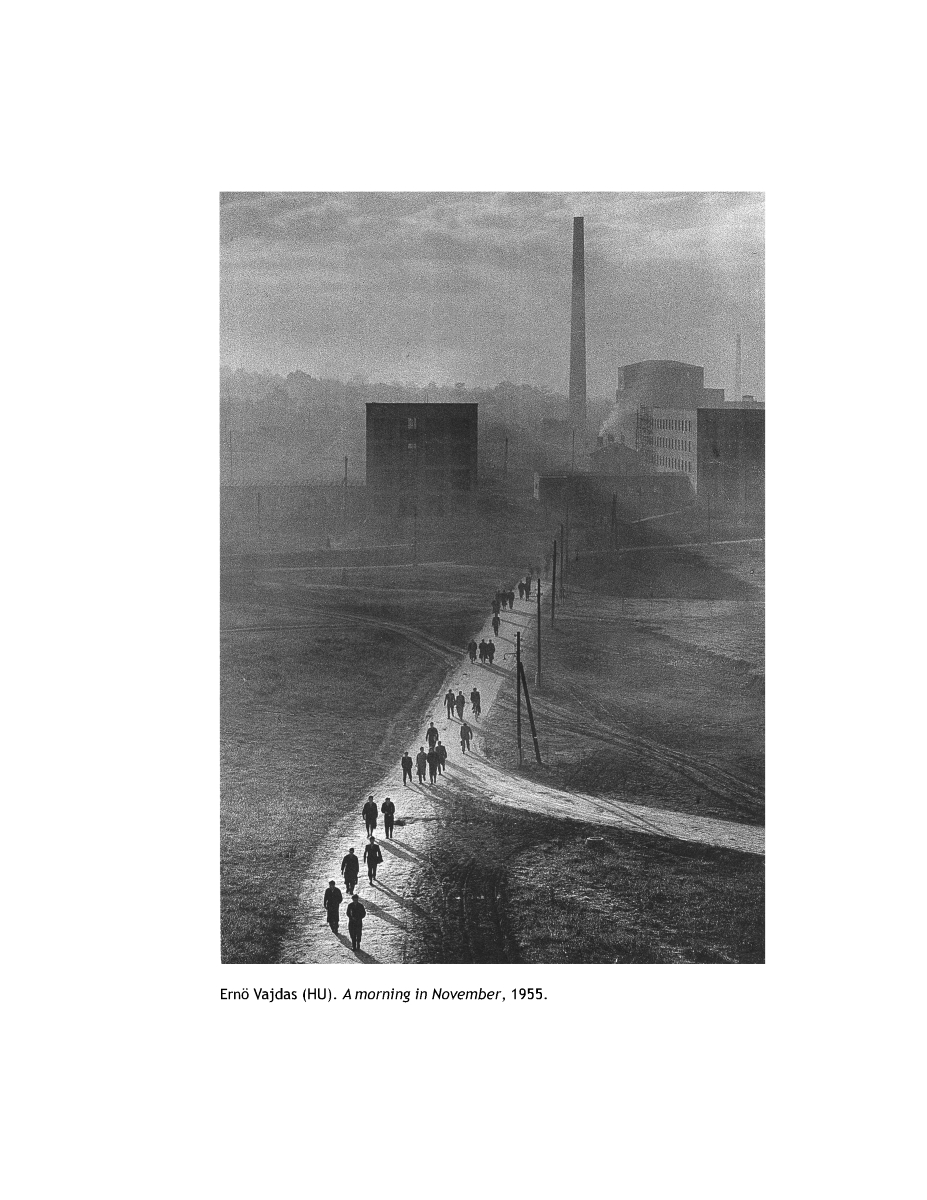

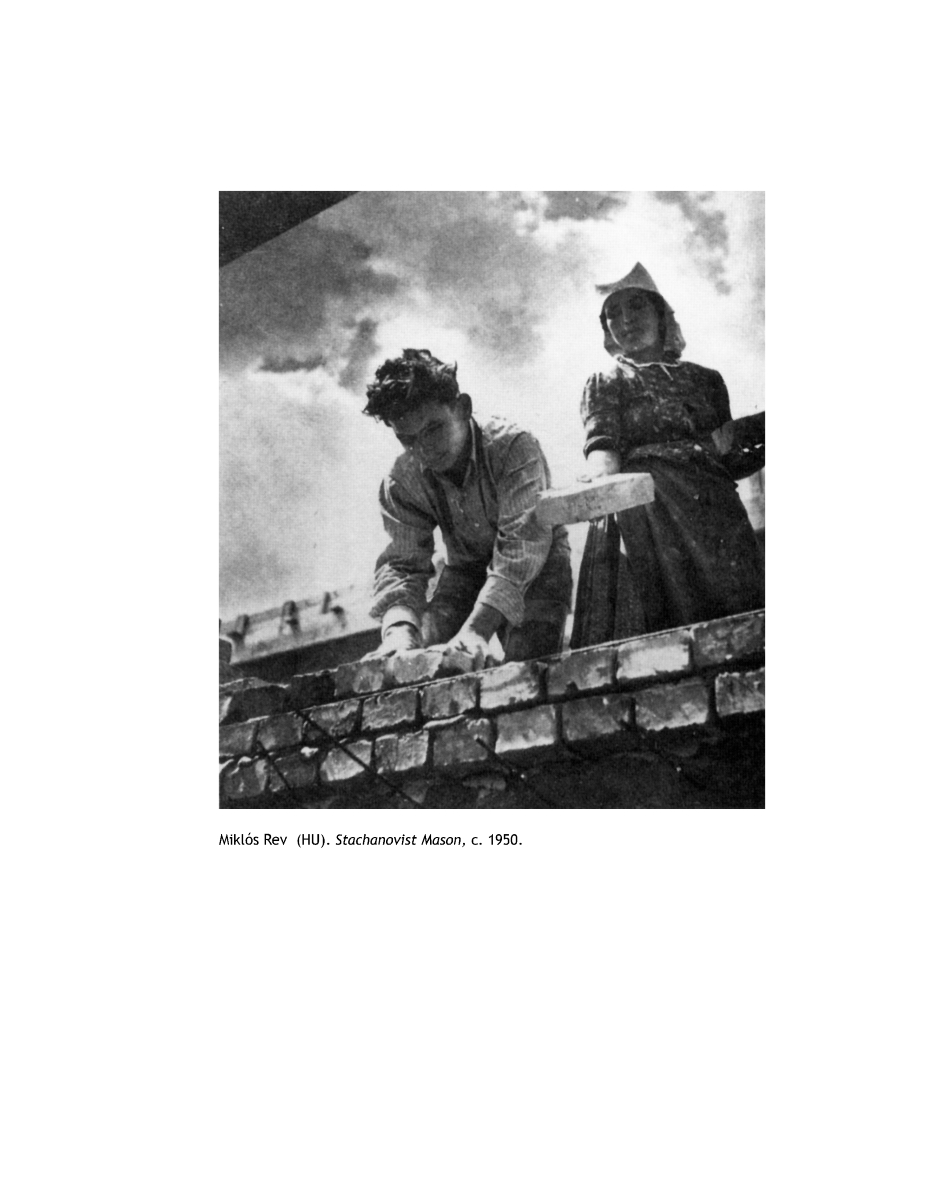

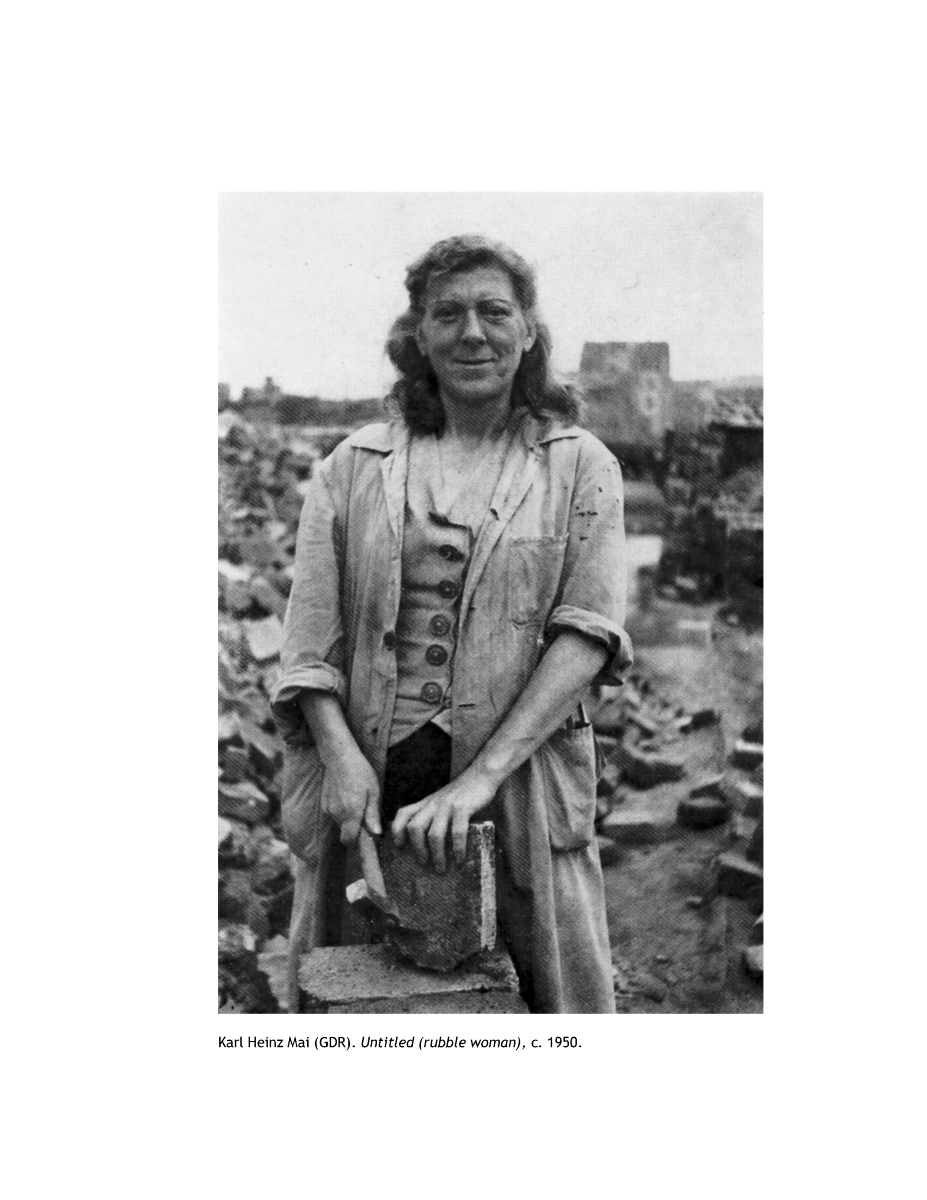

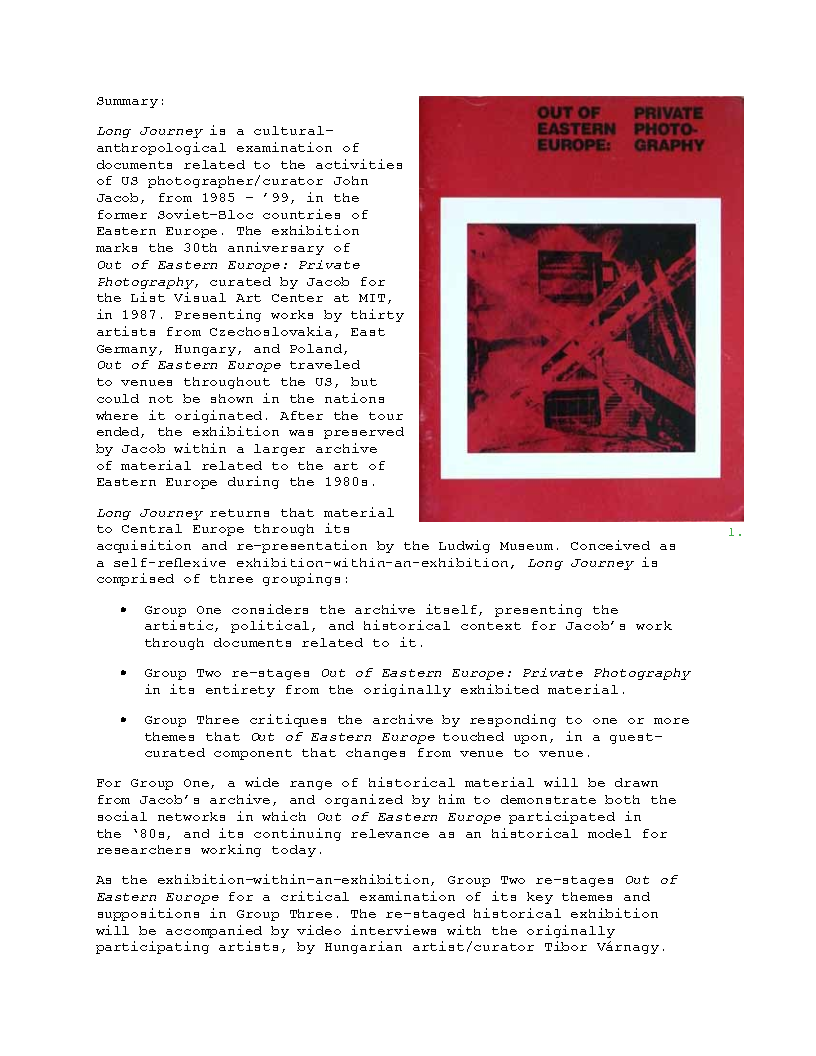

The idea went something like this: if you picture the perfect society, people will believe they are living in it and strive harder to make it come true. Photographers followed directions in order to work, but some circumvented them in whatever small ways they could. -- Vicki Goldberg, review of Recollecting a Culture, NY Times, 1999

Introduction

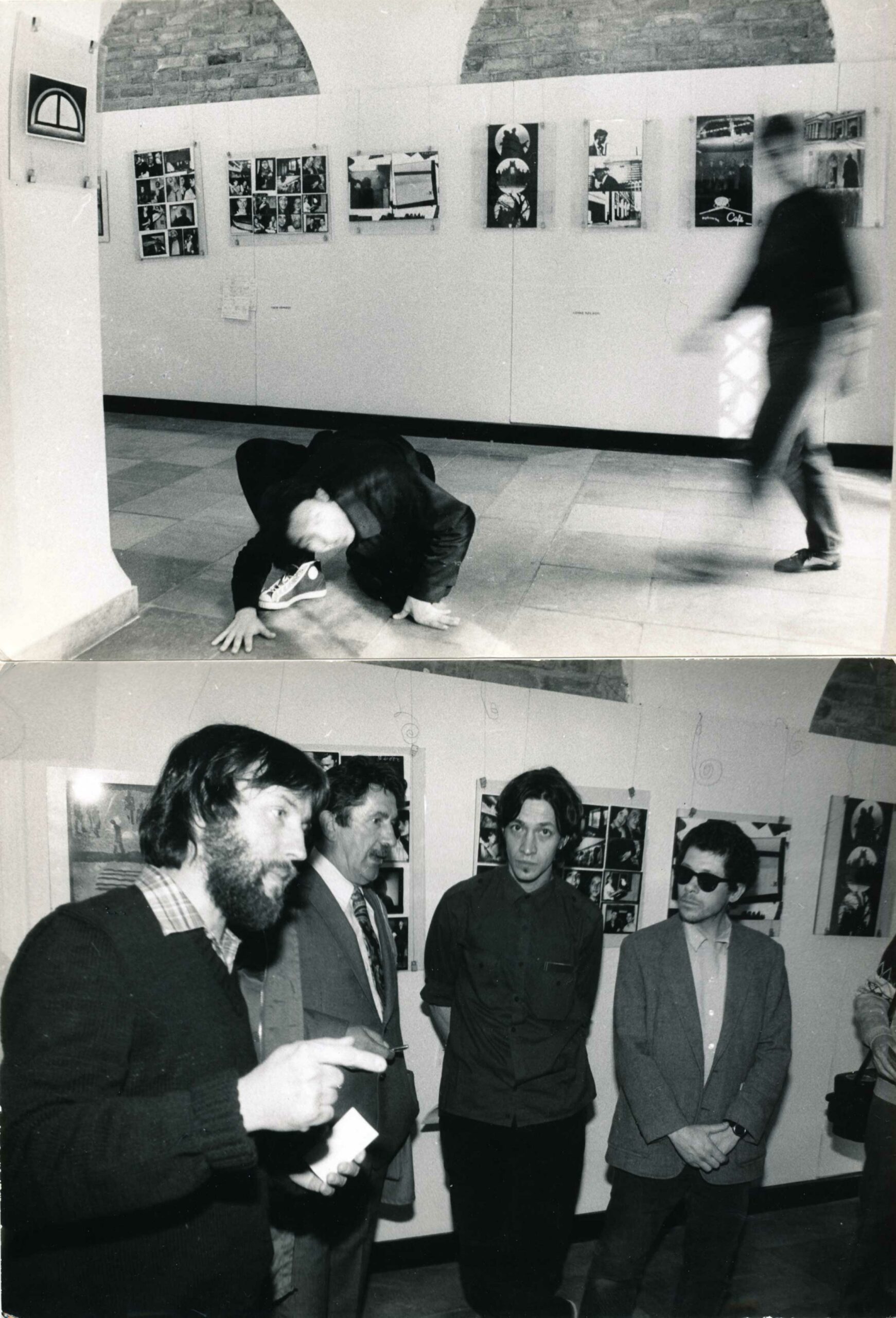

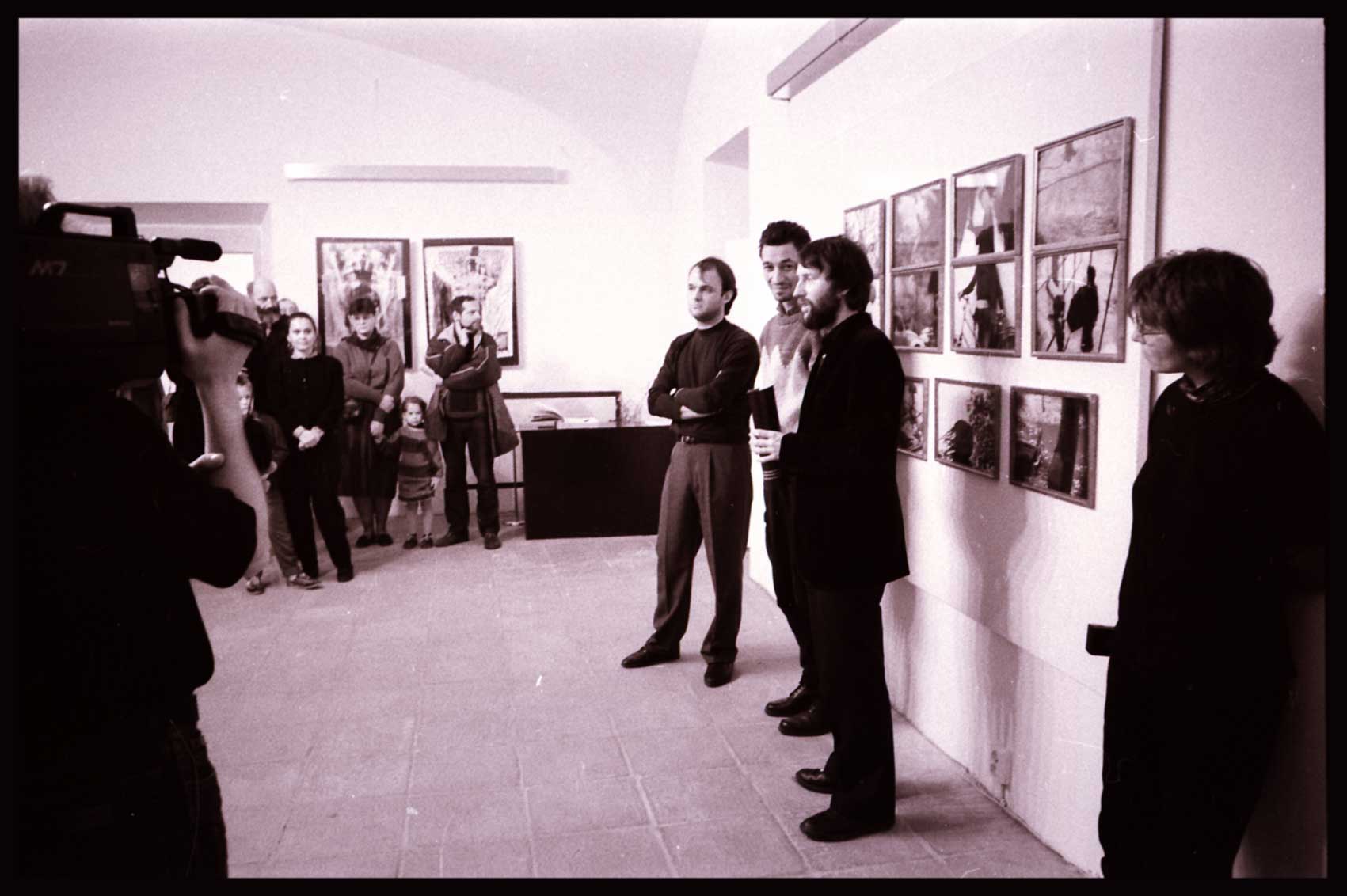

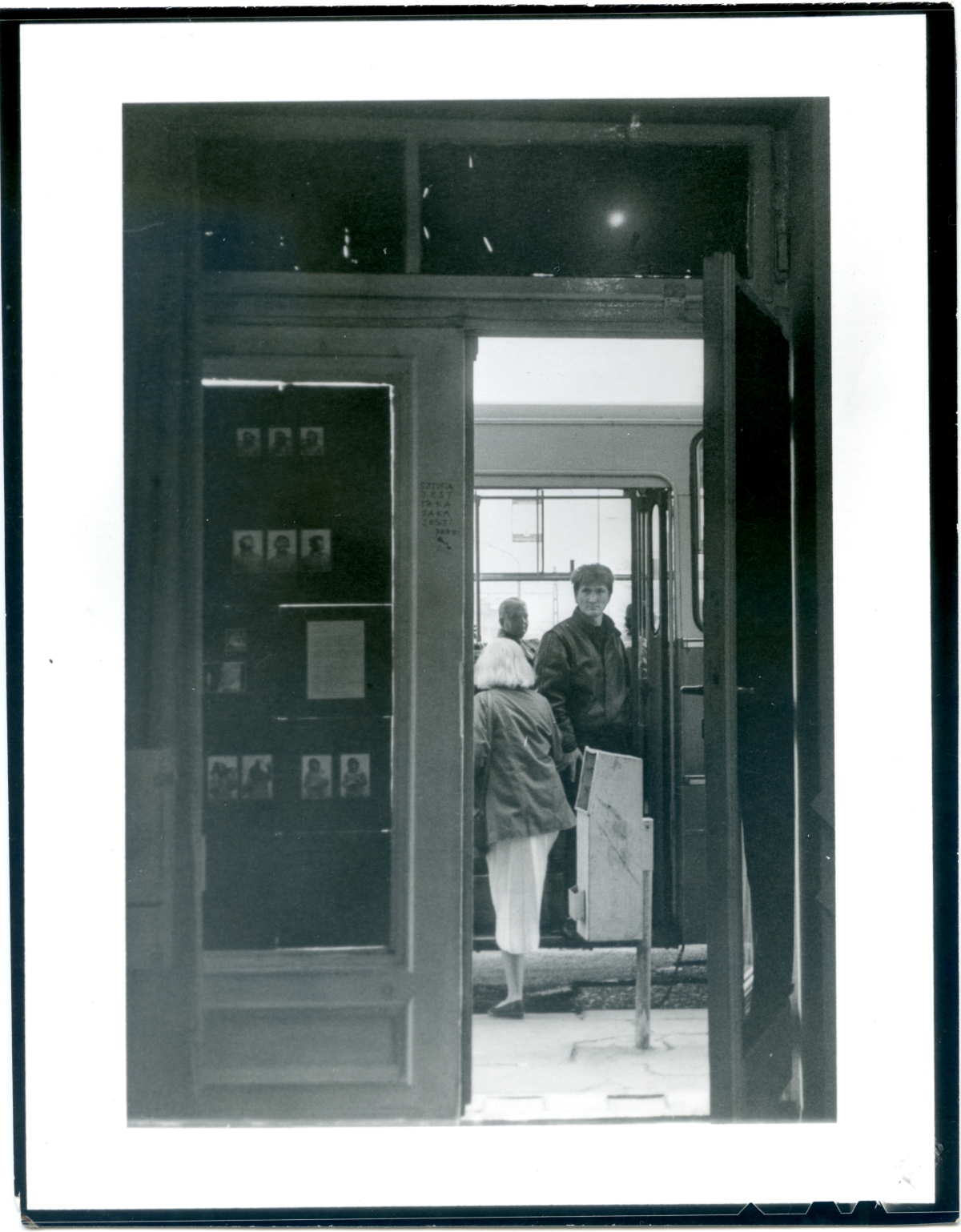

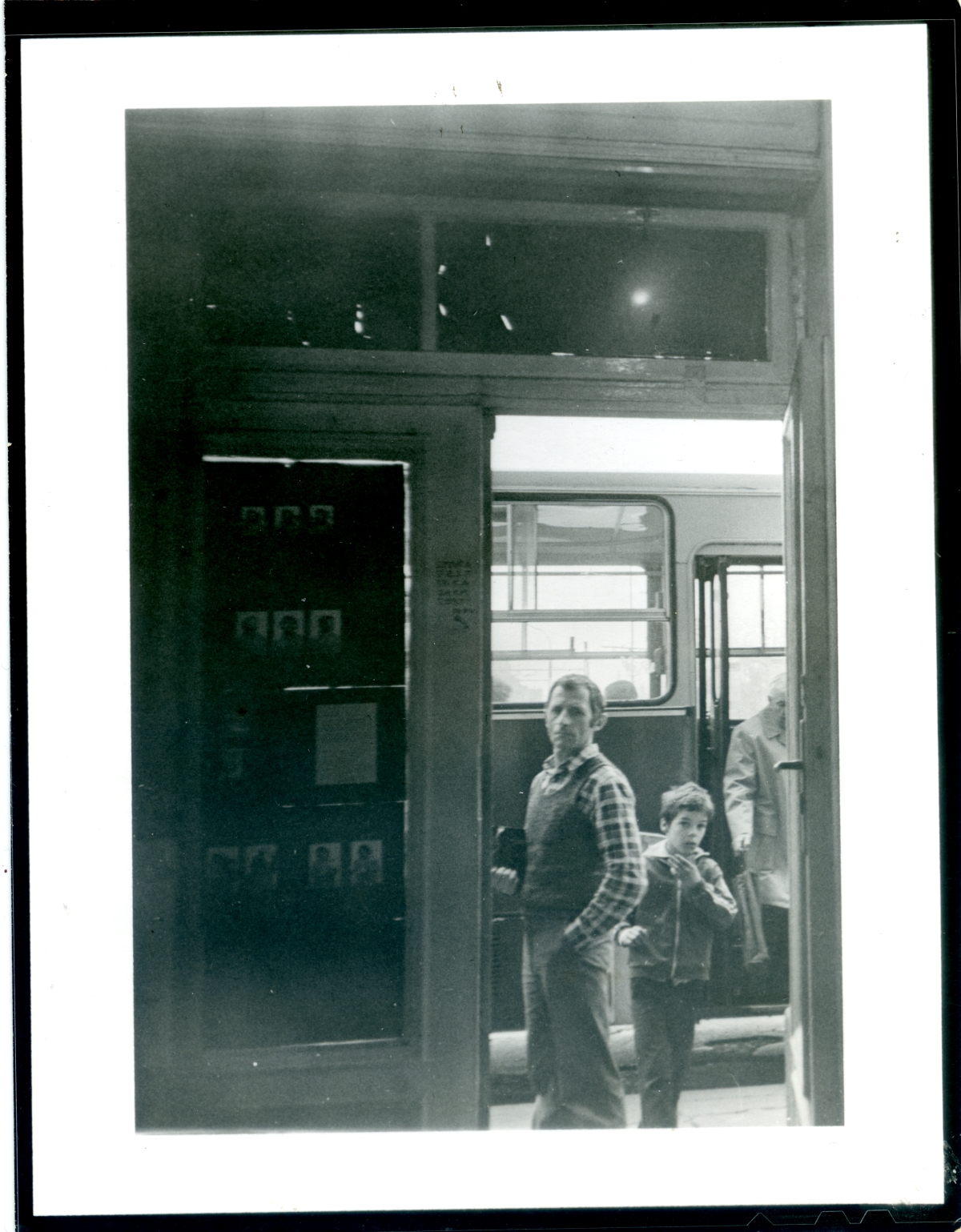

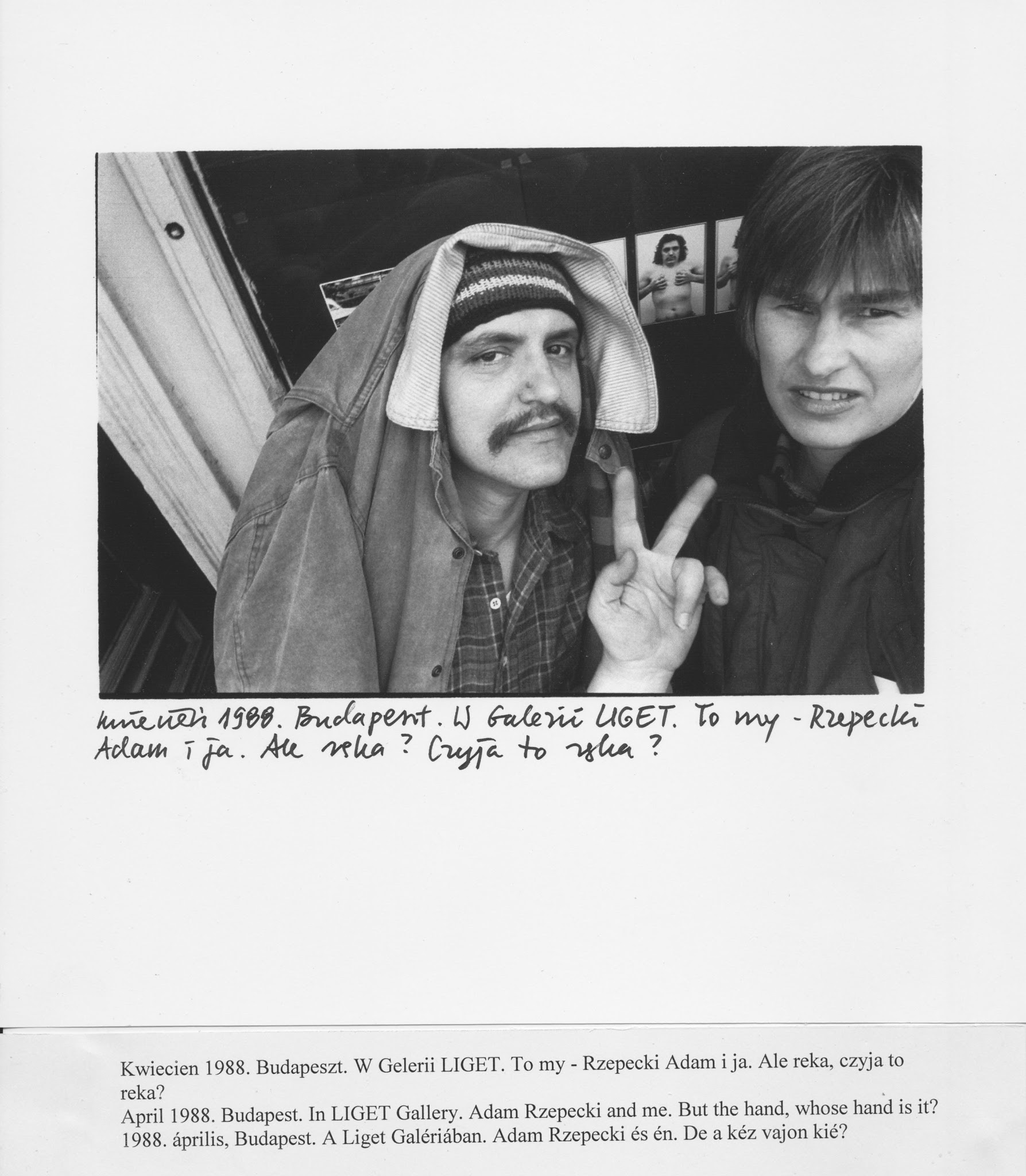

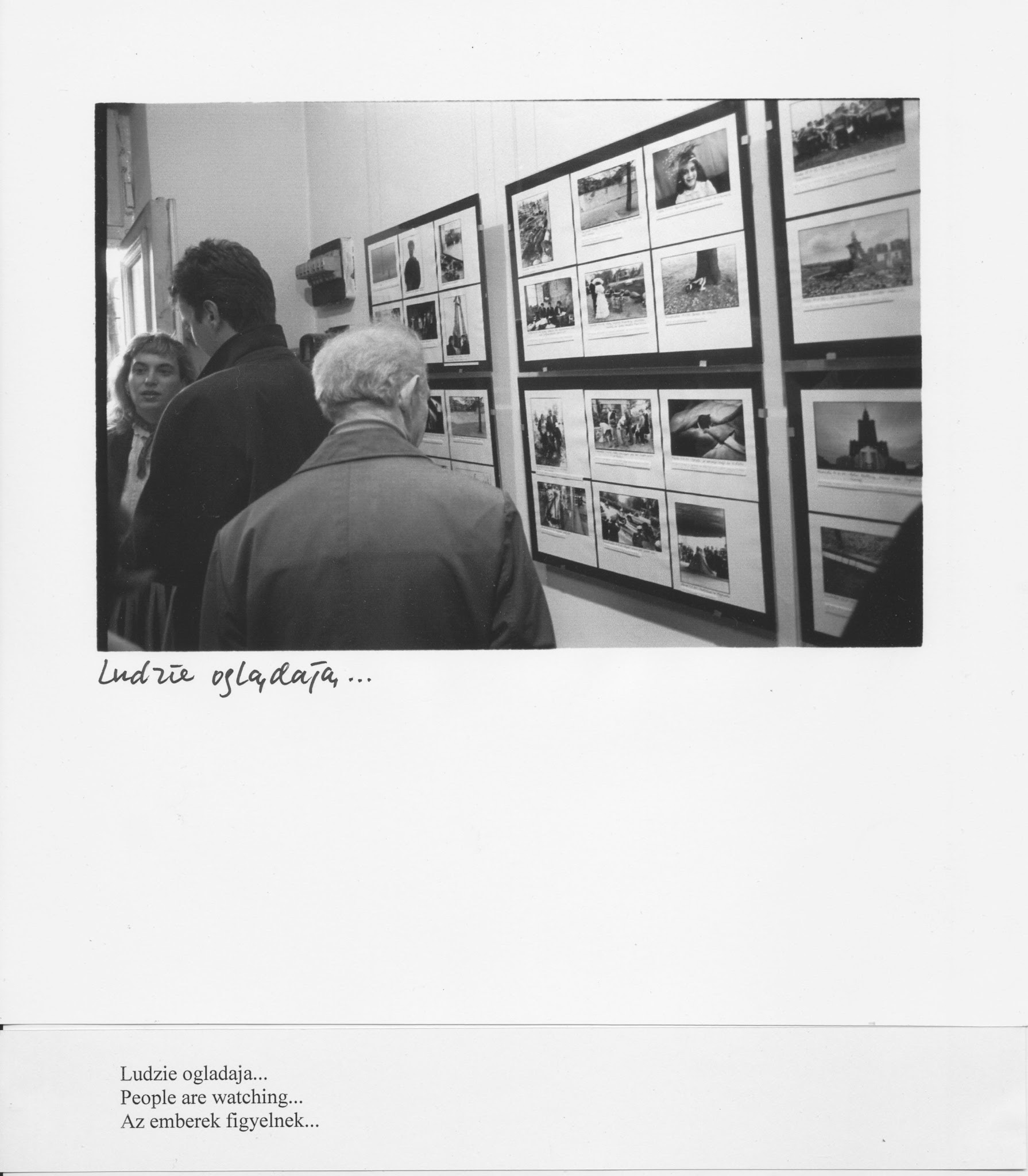

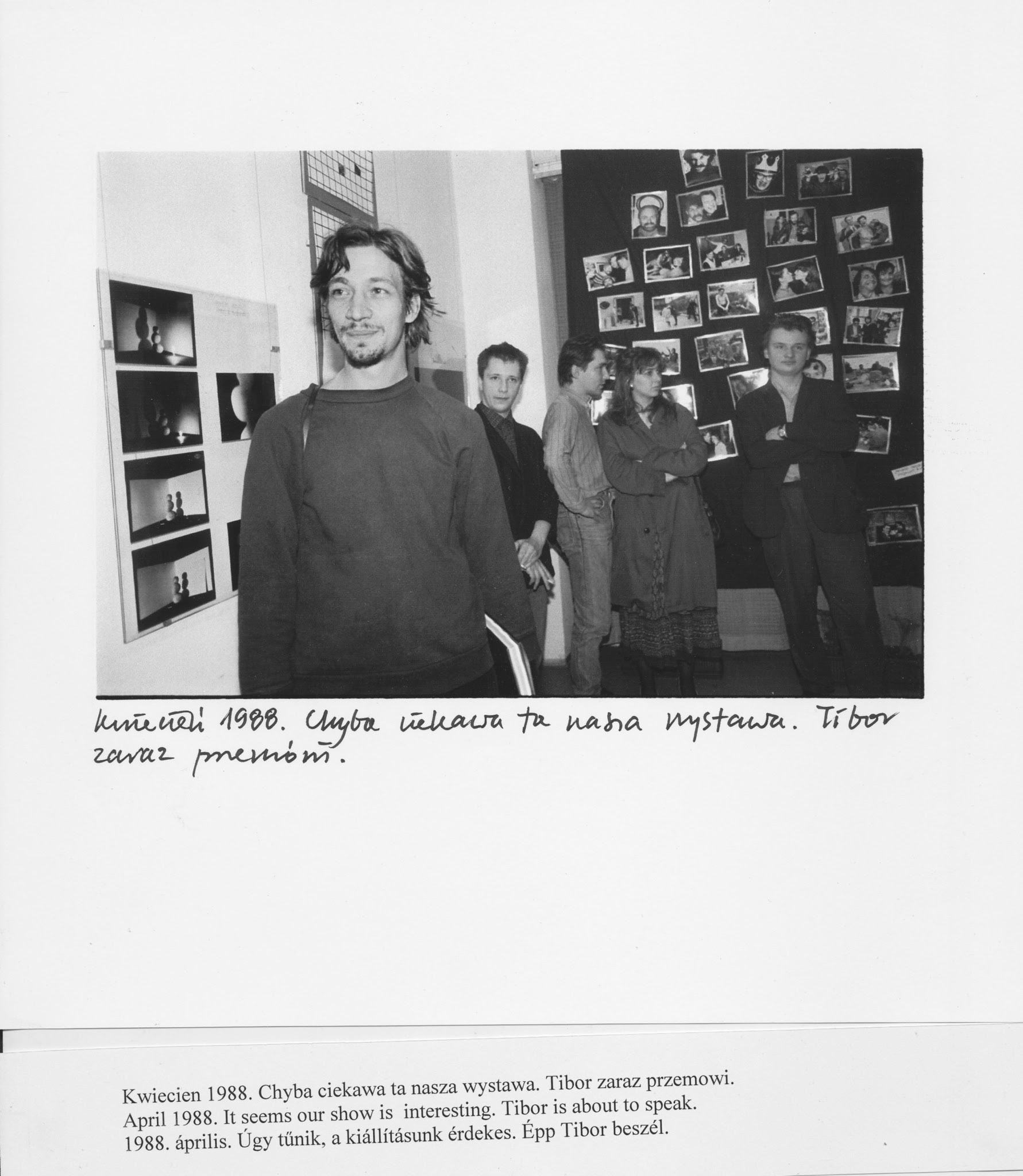

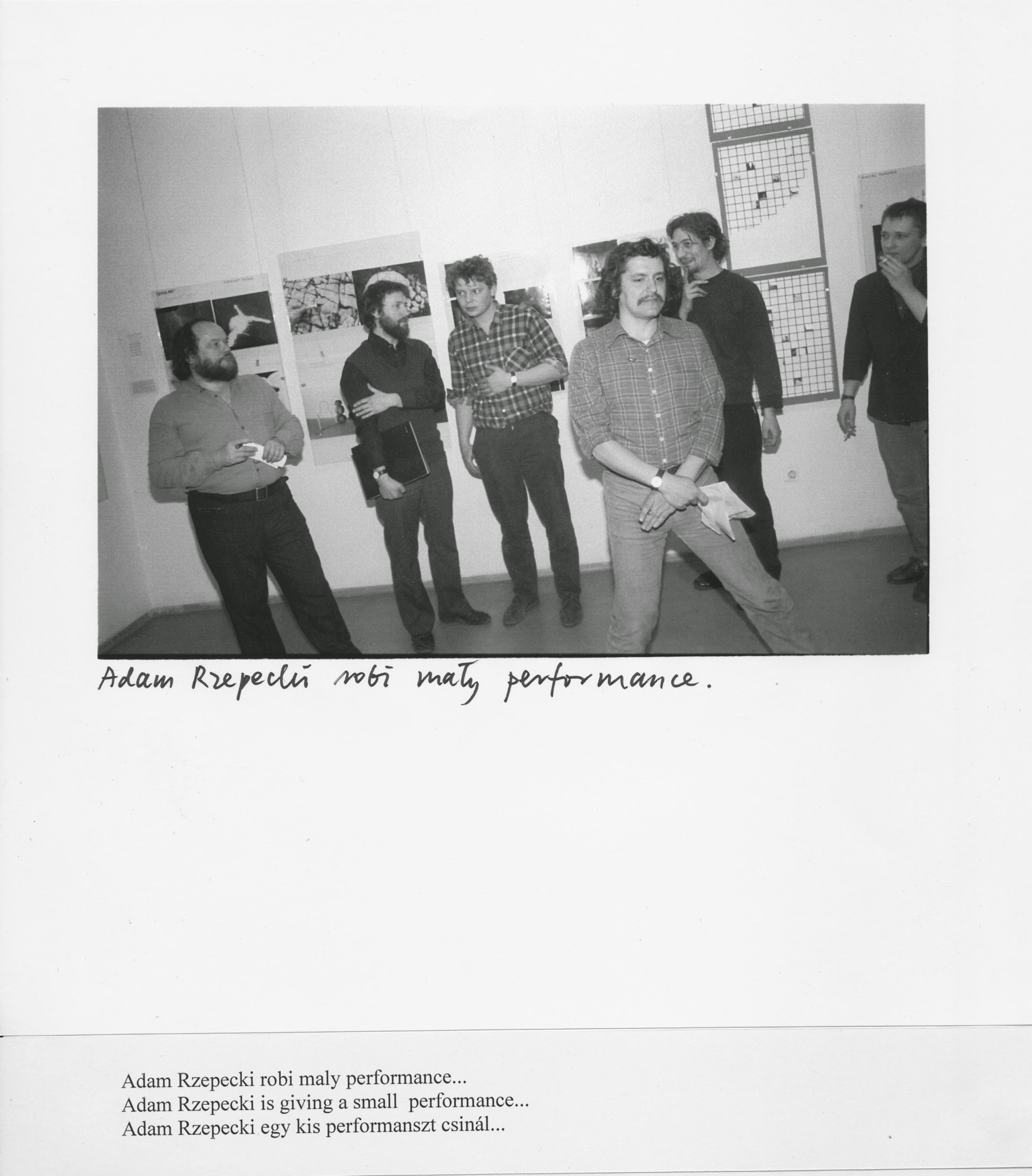

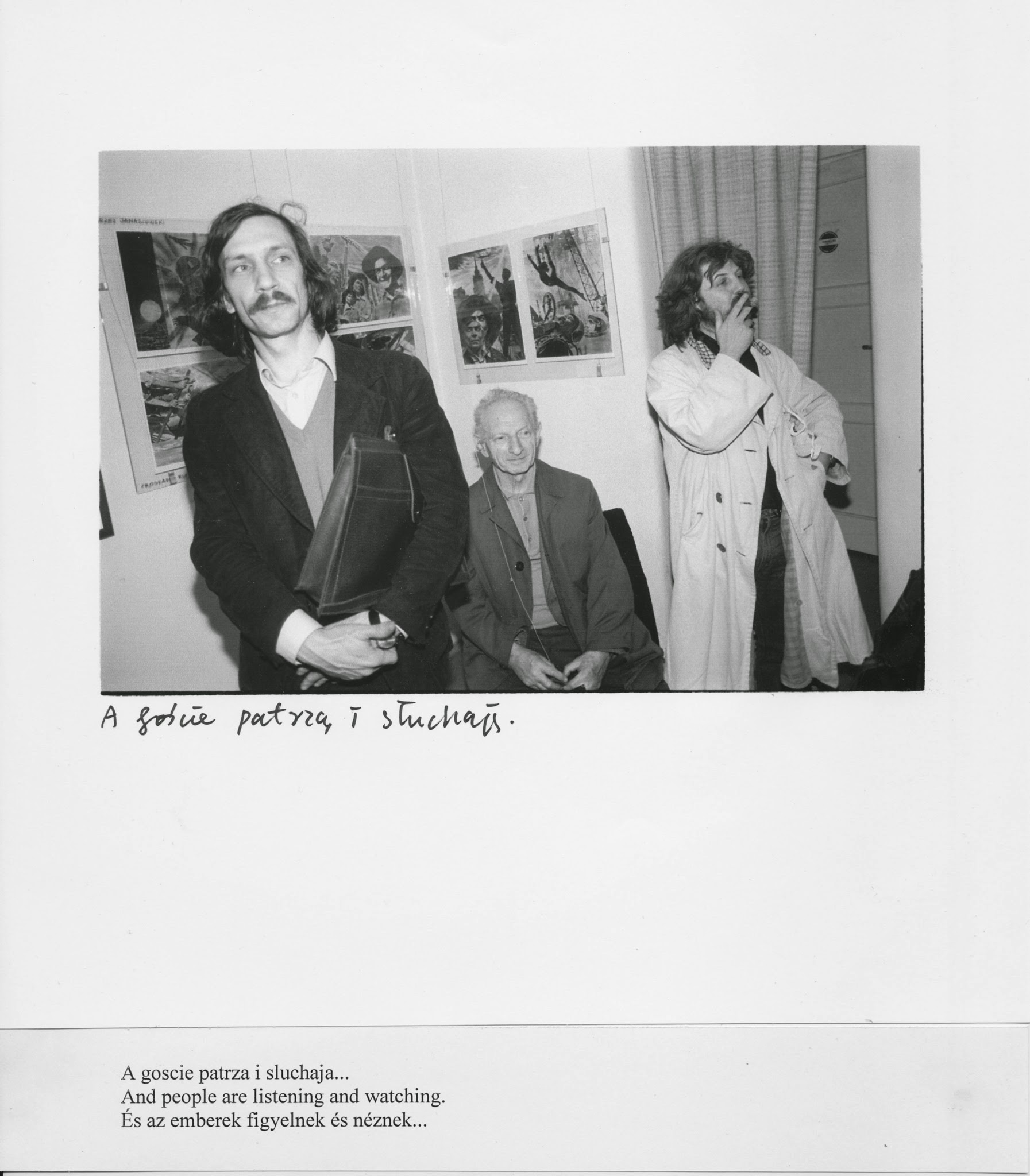

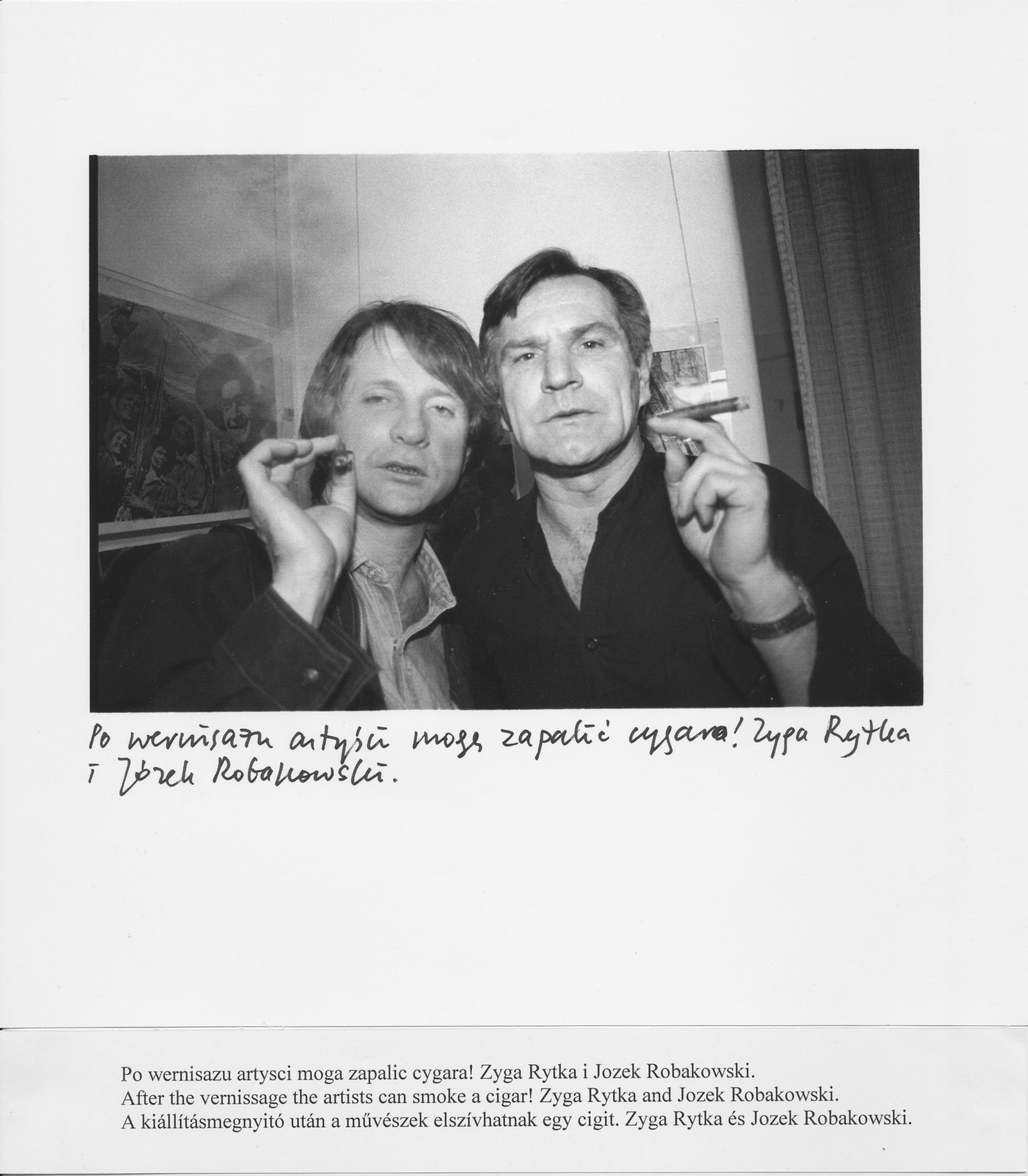

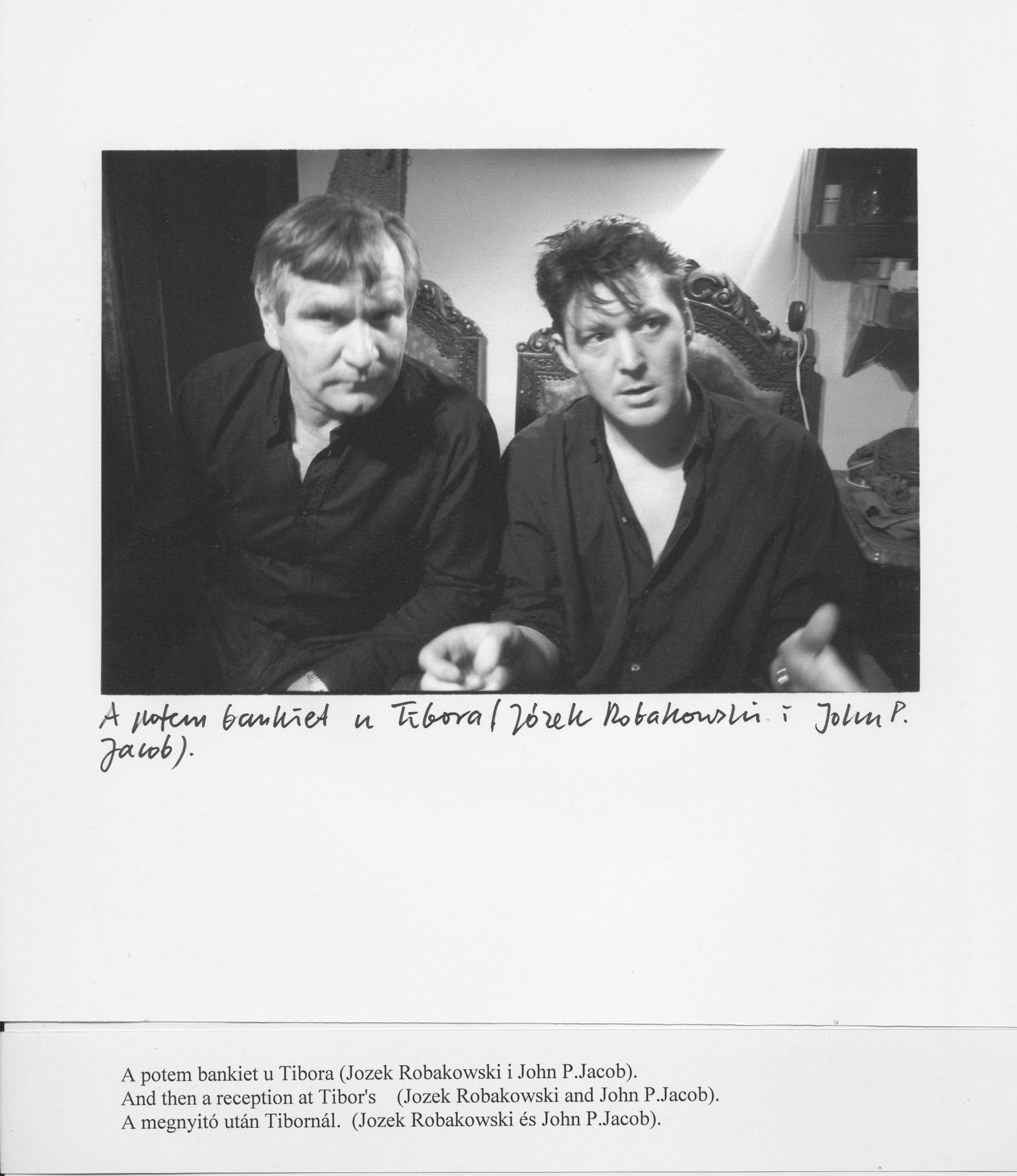

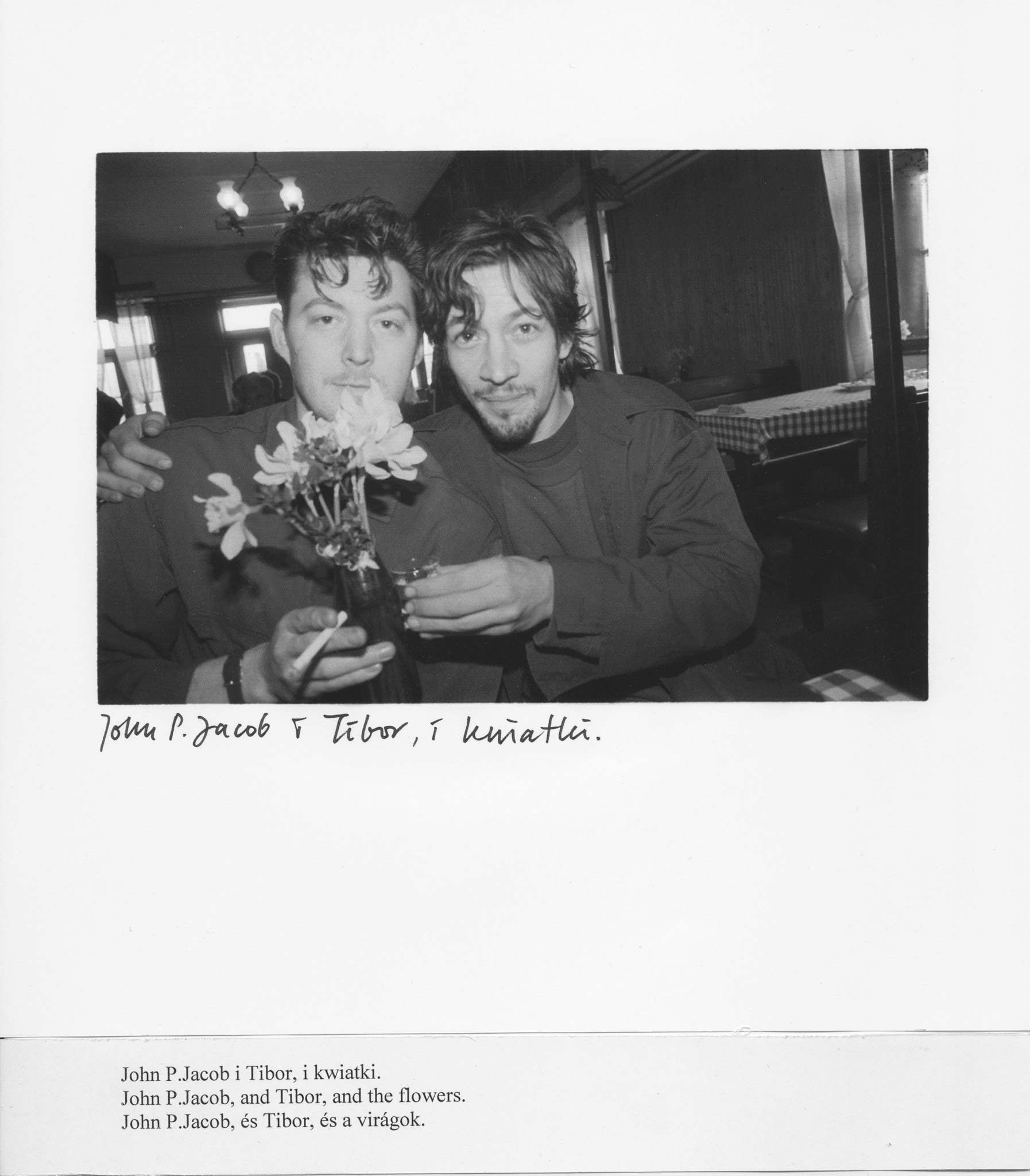

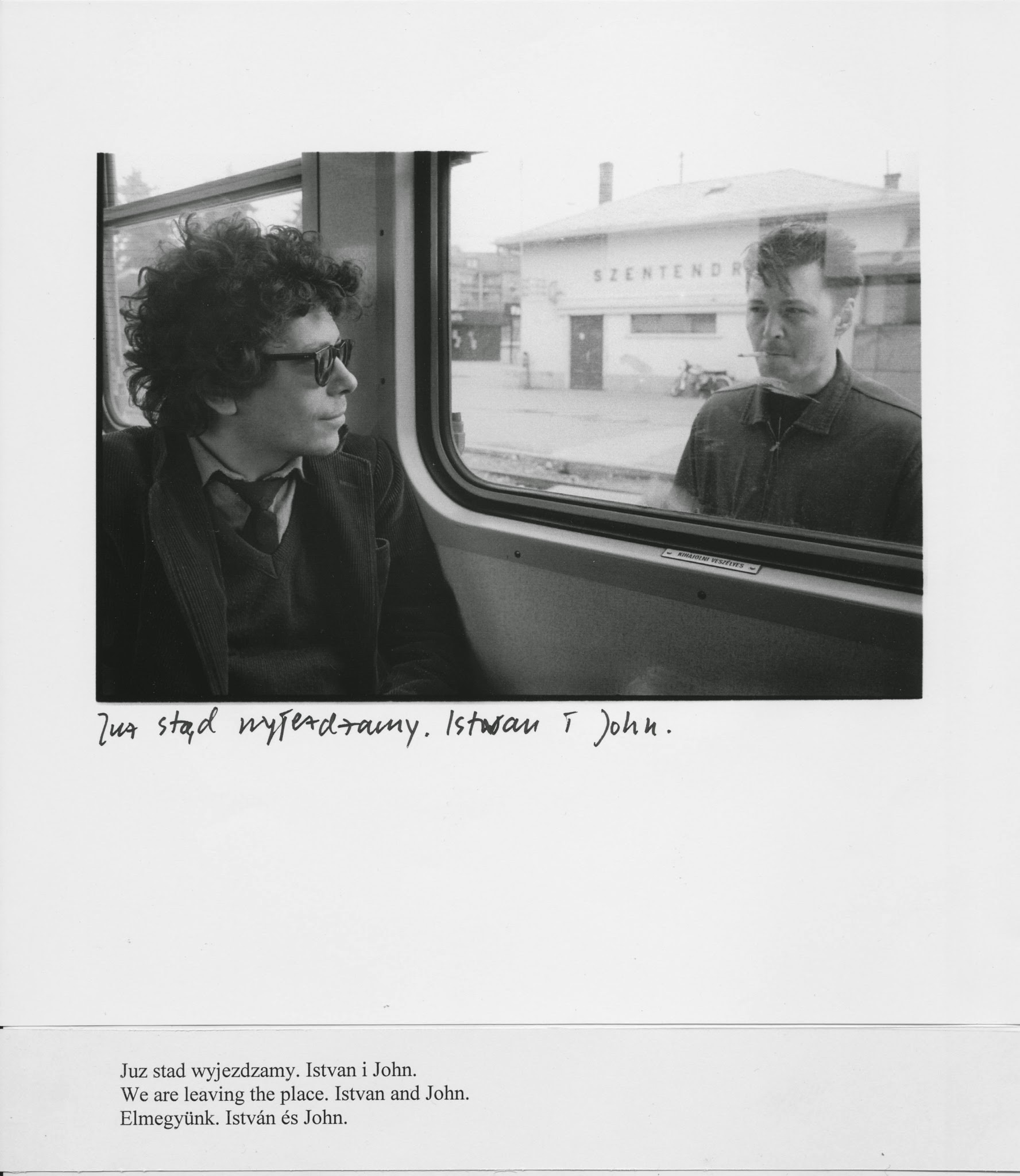

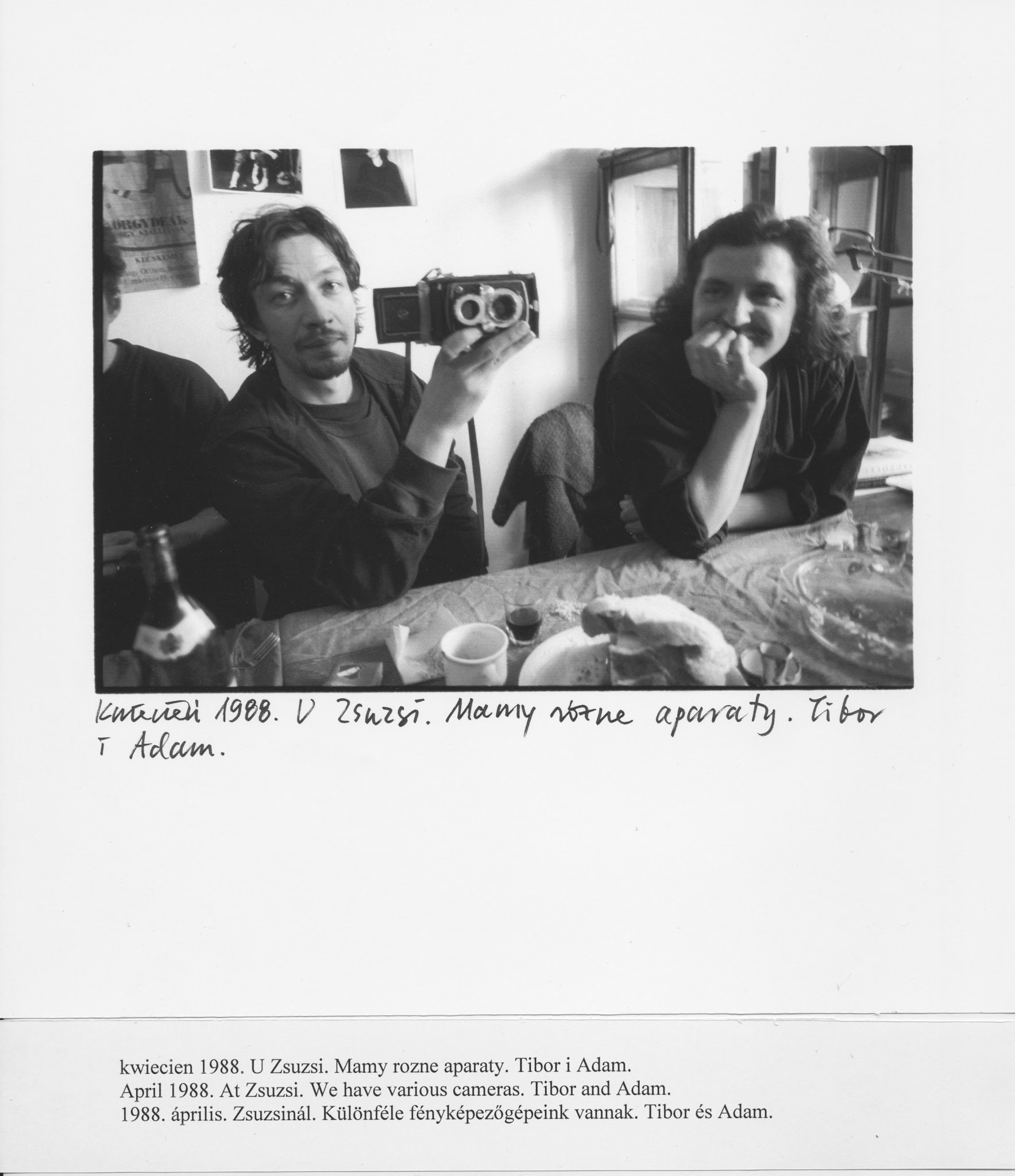

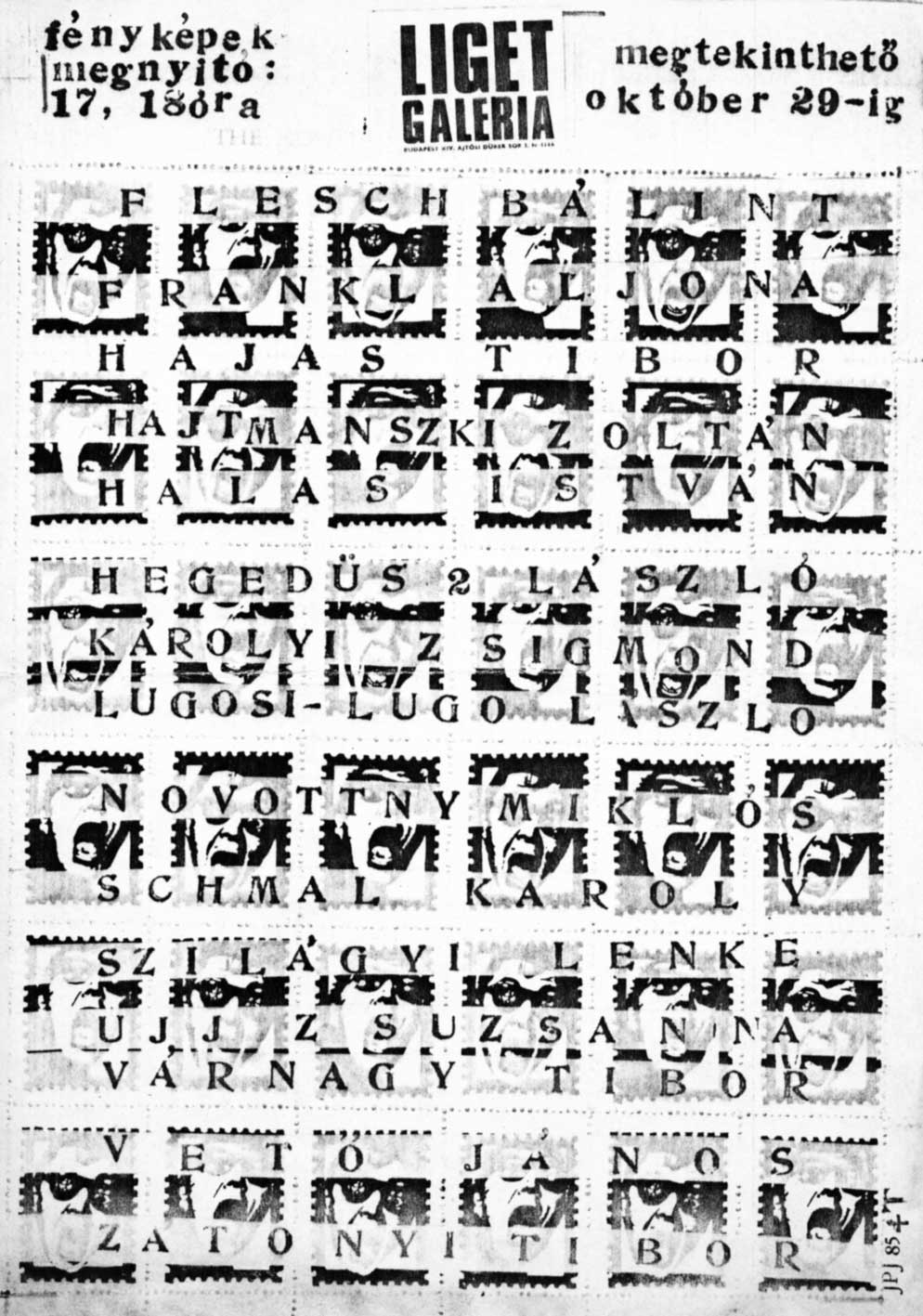

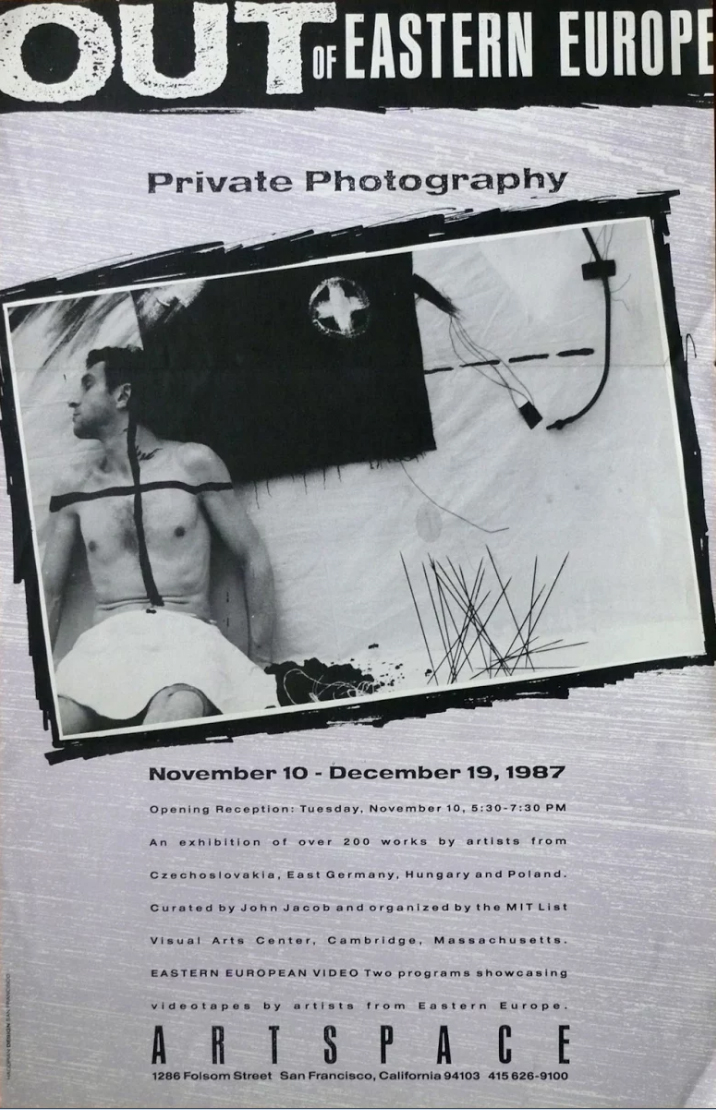

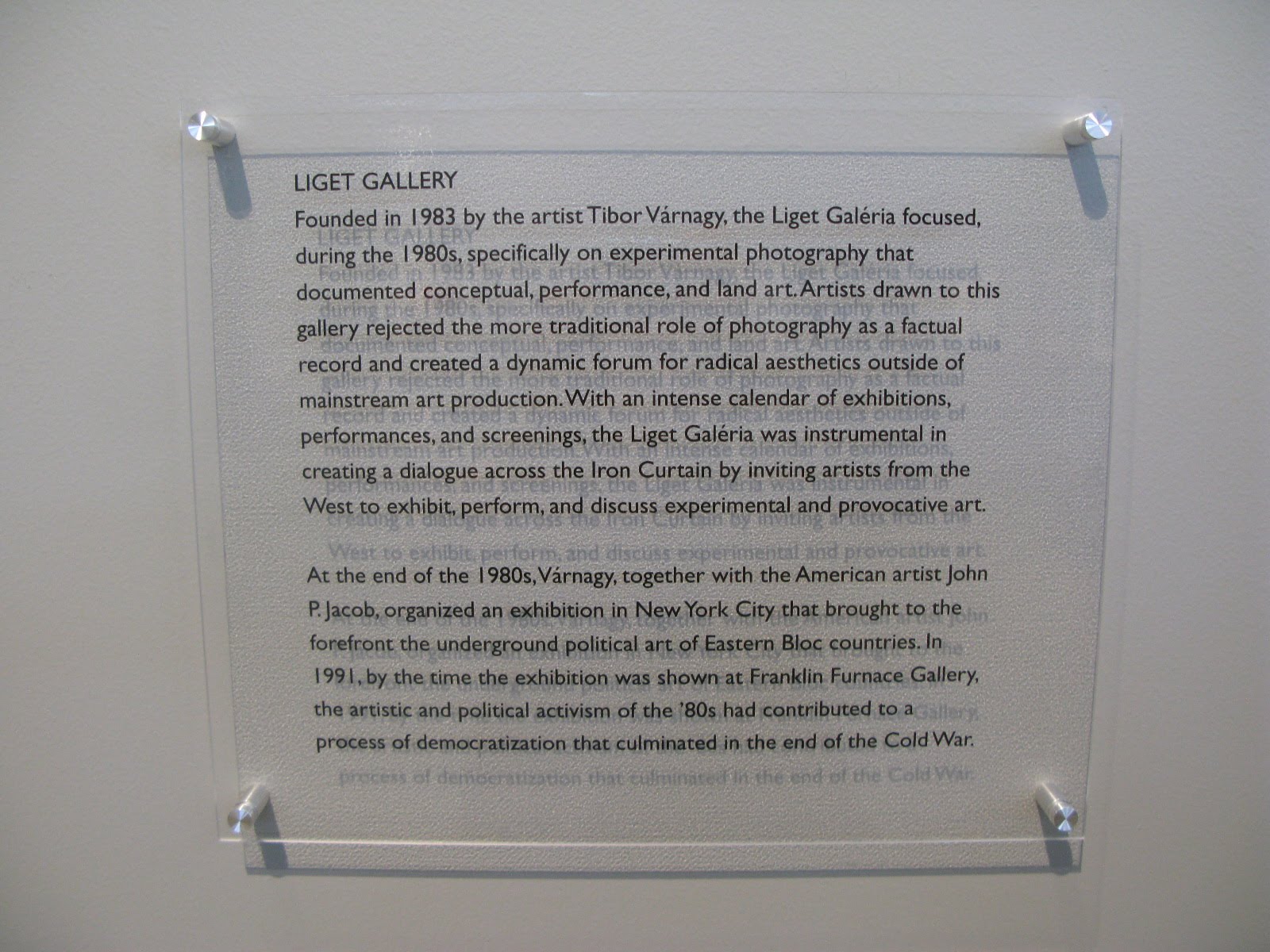

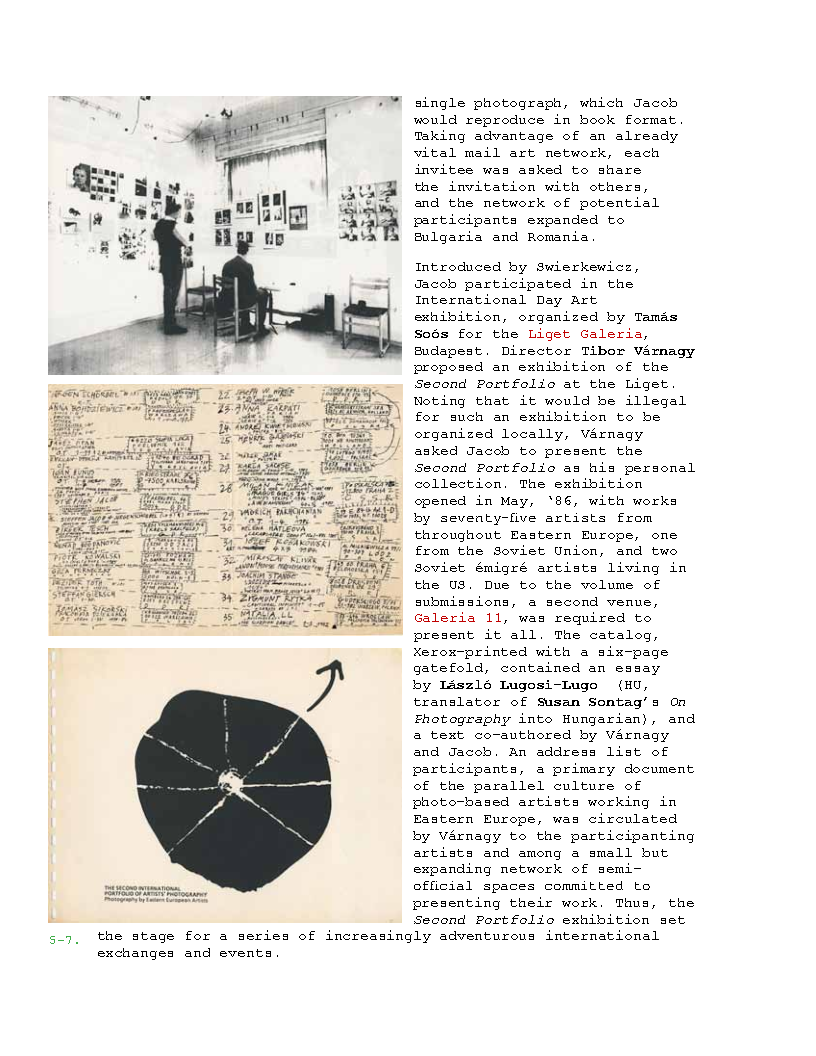

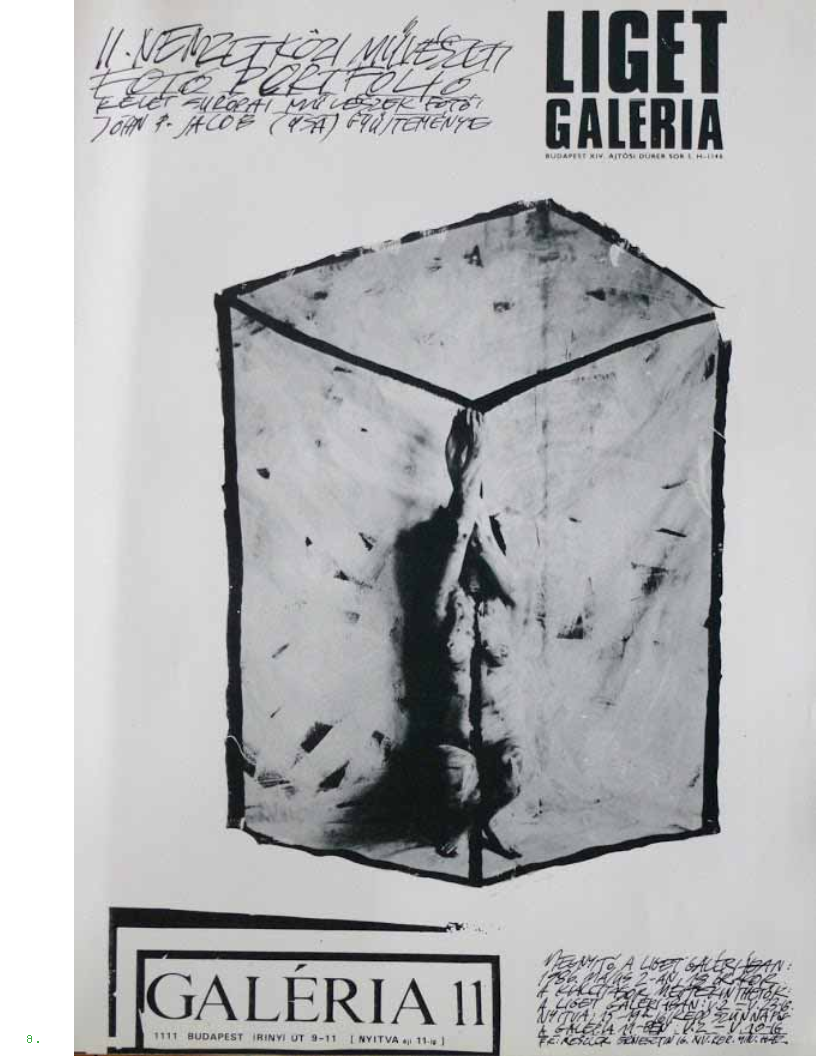

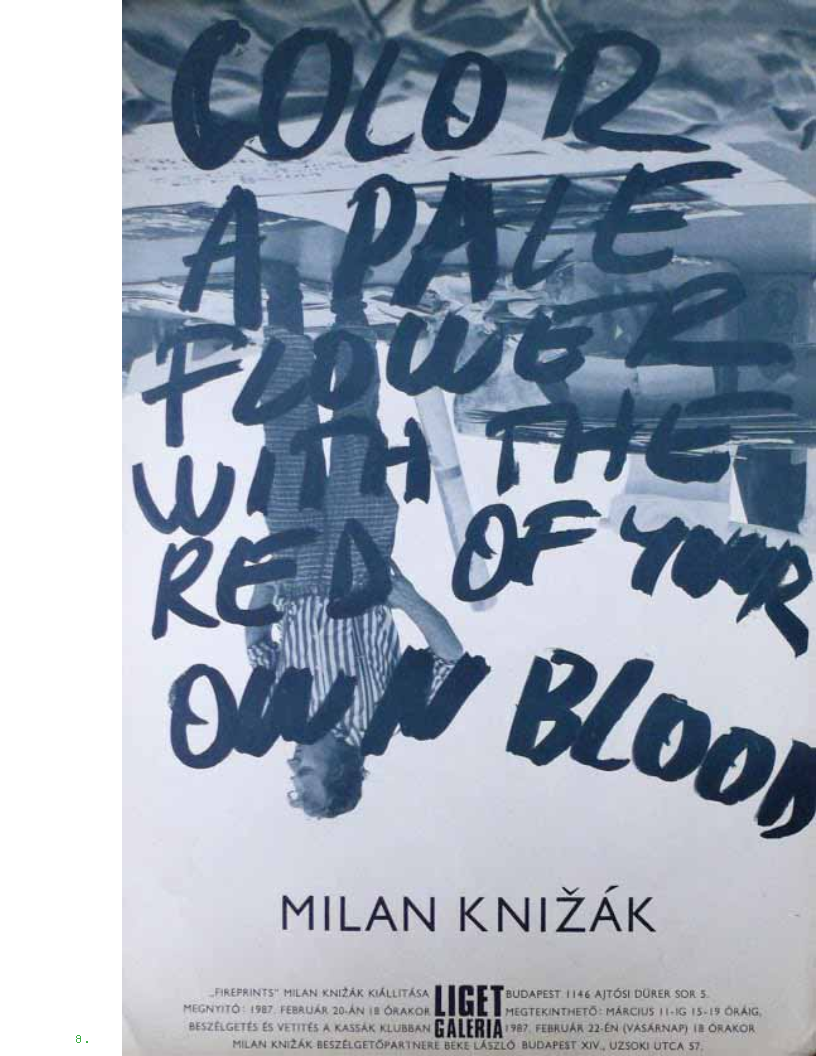

By 1989, with the opening of Eastern Europe, an international network of photo-based artists and of spaces dedicated to presenting their work was already well established. At the Liget Gallery, Várnagy presented one-person exhibitions by many of the international artists who had contributed to the Second Portfolio or Out of Eastern Europe, including Anna Bohdziewicz, Milan Knizák, Matthias Leupold, and Lodz Kaliska, and he expanded the international roster well beyond photography.

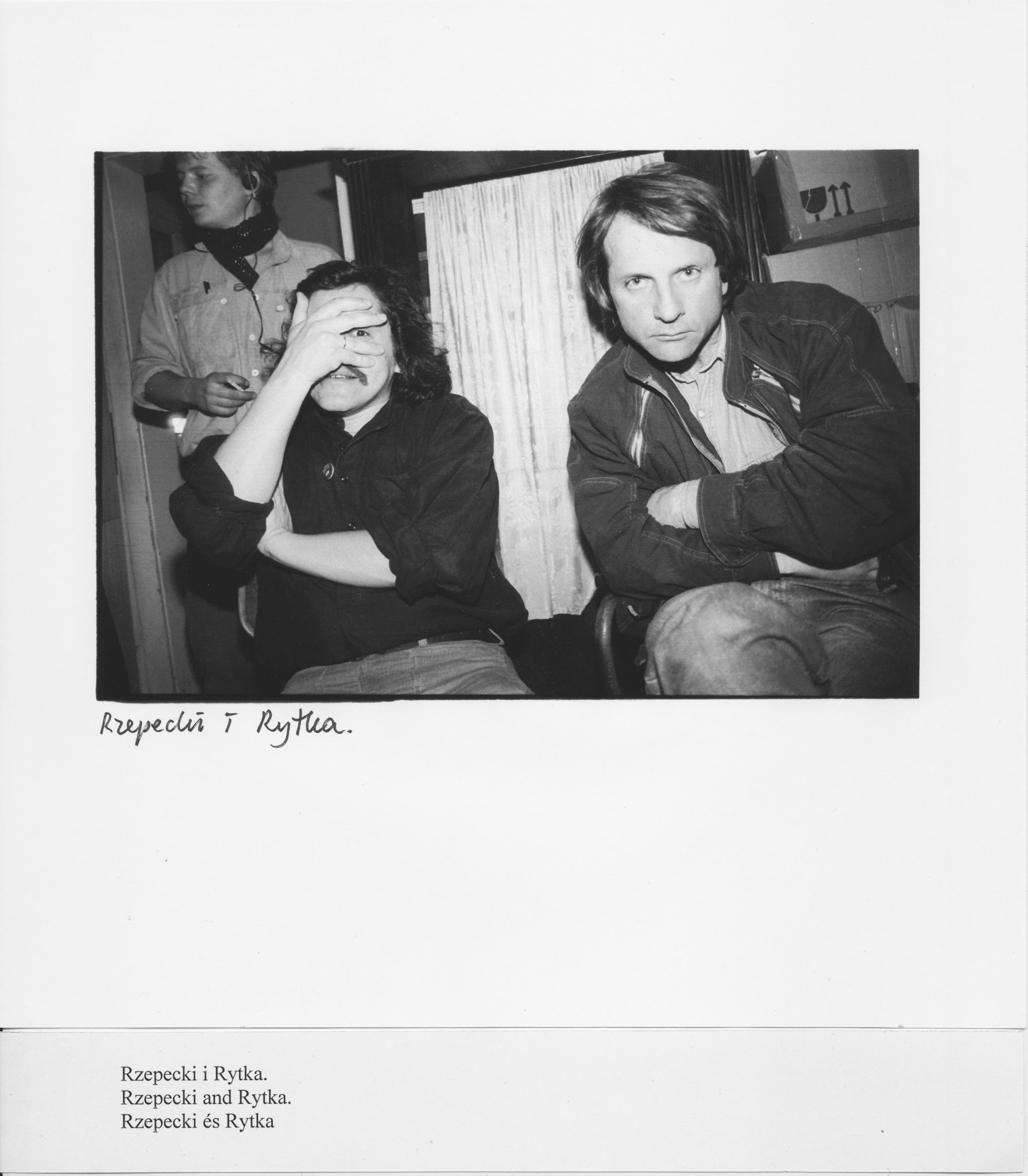

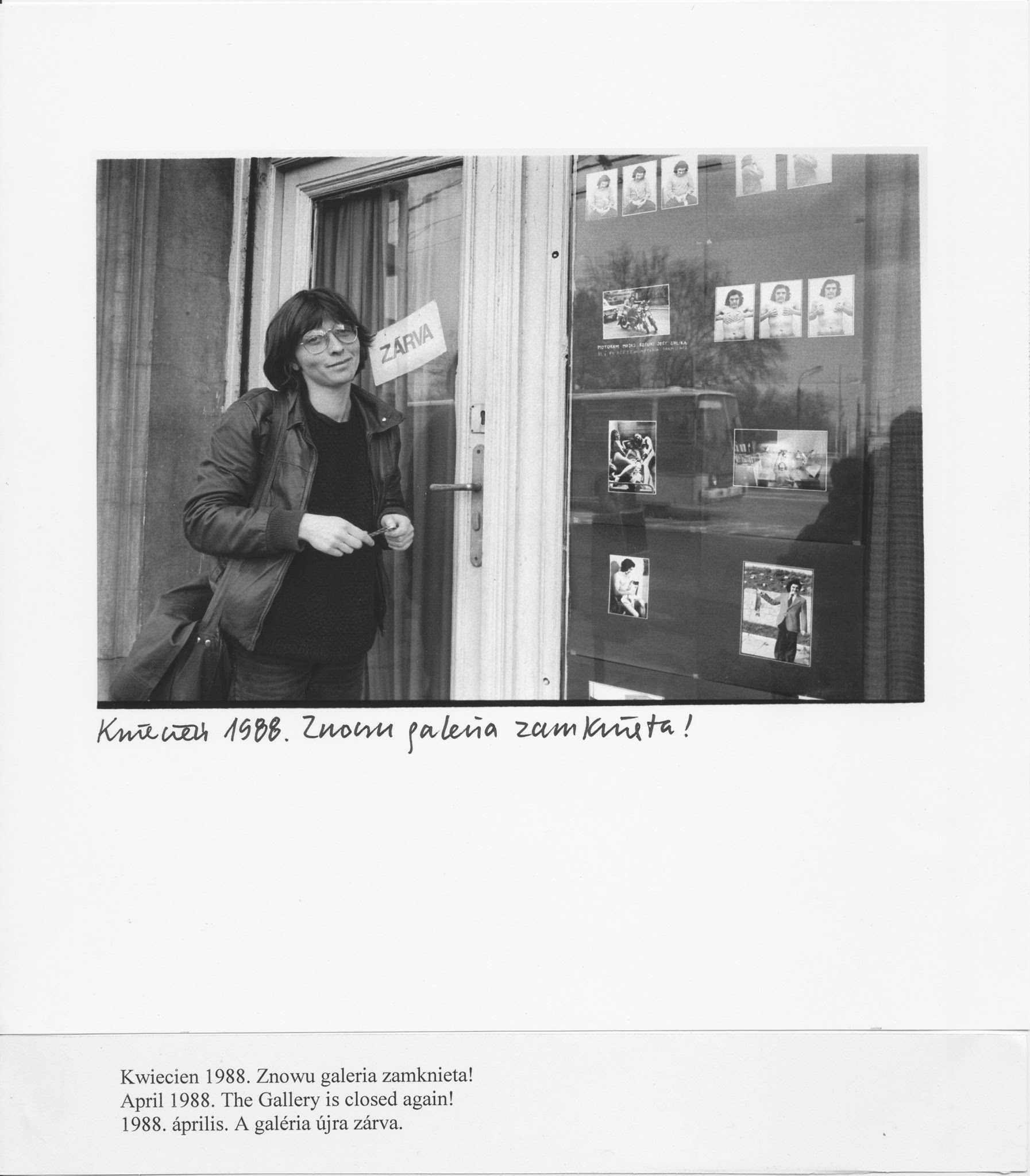

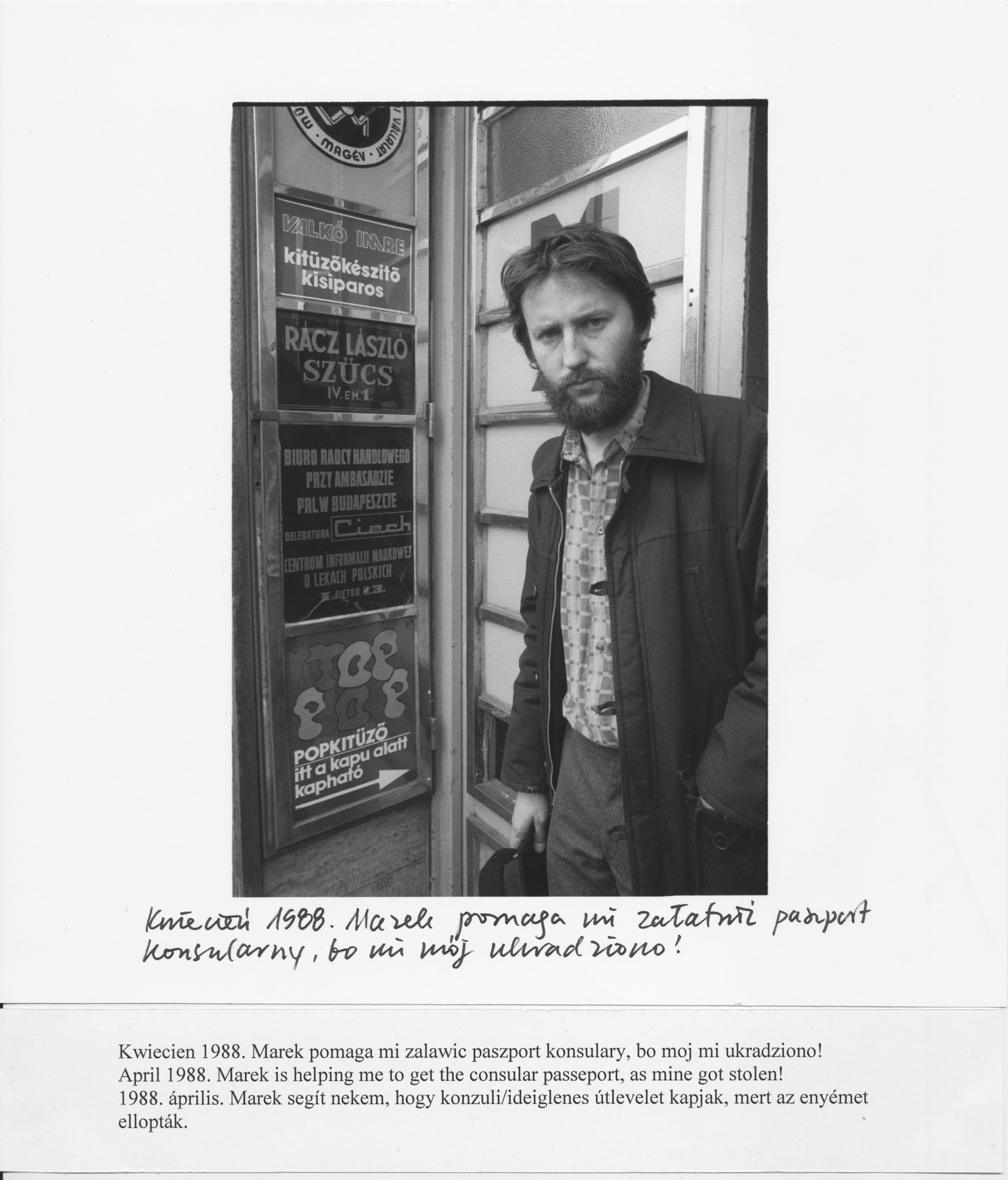

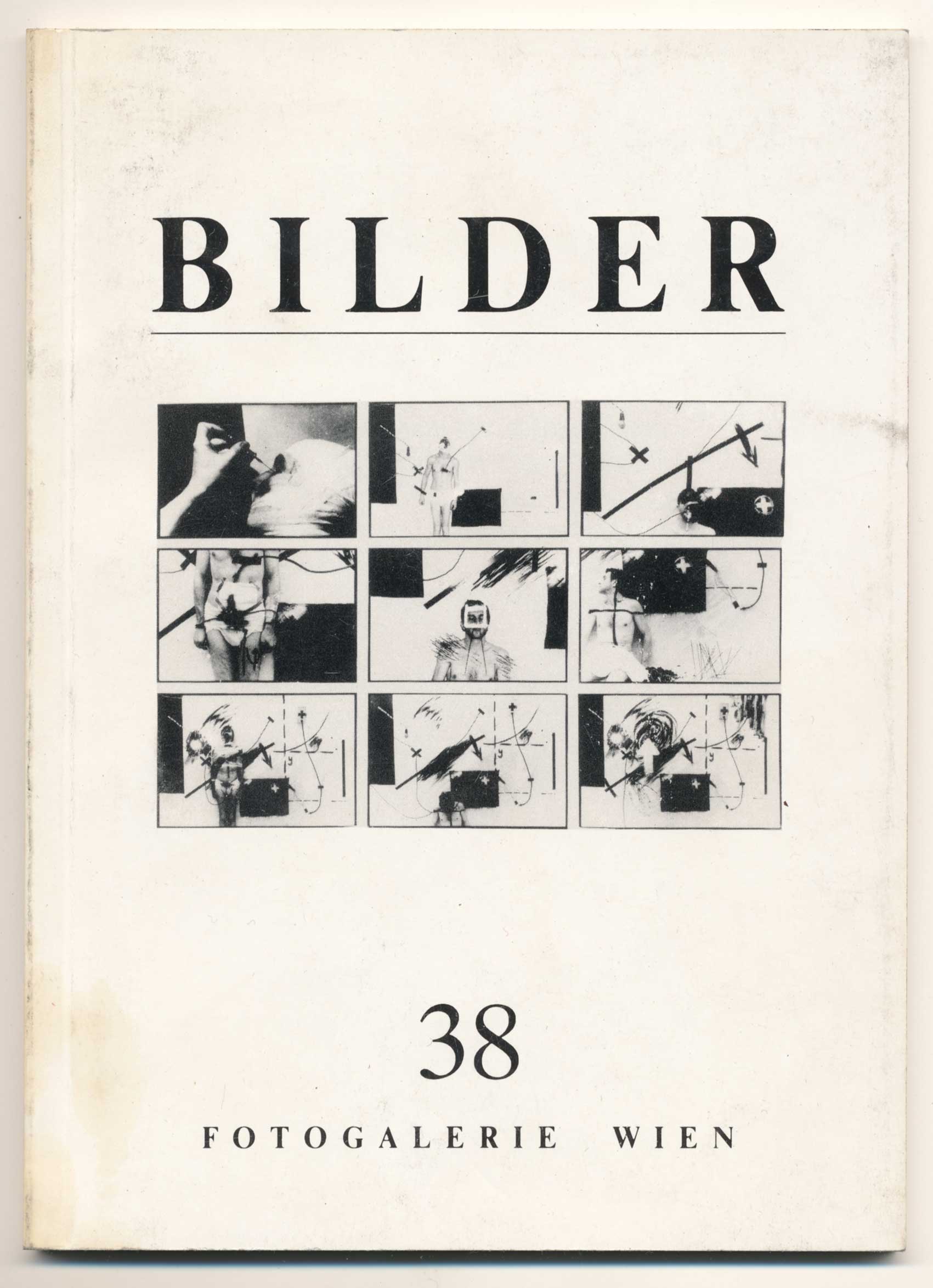

In 1987, the exhibition Fotografia (Frankl Aljona, Halas István, Hegedüs 2 László, László Lugosi-László, Szilágyi Lenke, Várnagy Tibor, and Zátonyi Tibor) was the first of several exchanges between the Liget and the Mala Gallery in Warsaw, led by Marek Grygiel. In 1989, Zeitgenossische Ungarische Fotografie was the first of several exchanges between the Liget and Fotogalerie Wien, curated by Dr. Gerlinde Schrammel and with an essay by Jacob. Also in 1990, Várnagy, with co-curators Marek Grygiel and Robert Waldl, organized the exhibitions Fotoanarchiv: New Photography from Austria and Hungary for the Centre of Contemporary Art, Warsaw, and, in 1991, Fotoanarchiv II: Creative Photography from Austria, Poland, and Hungary for Szombathelyi Képtár. The Fotoanarchiv exhibitions brought together Austrian media-based artists, including Heinz Cibulka and Michaela Moscouw, with their Polish and Hungarian counterparts. In cooperation with Austrian artist Josef Wais, Várnagy organized the Eastern Academy of Photography in Vienna, a series of workshops and exhibitions introducing Czech artists Rudo Prekop, Kamil Varga, and Peter Zupnik, among others.

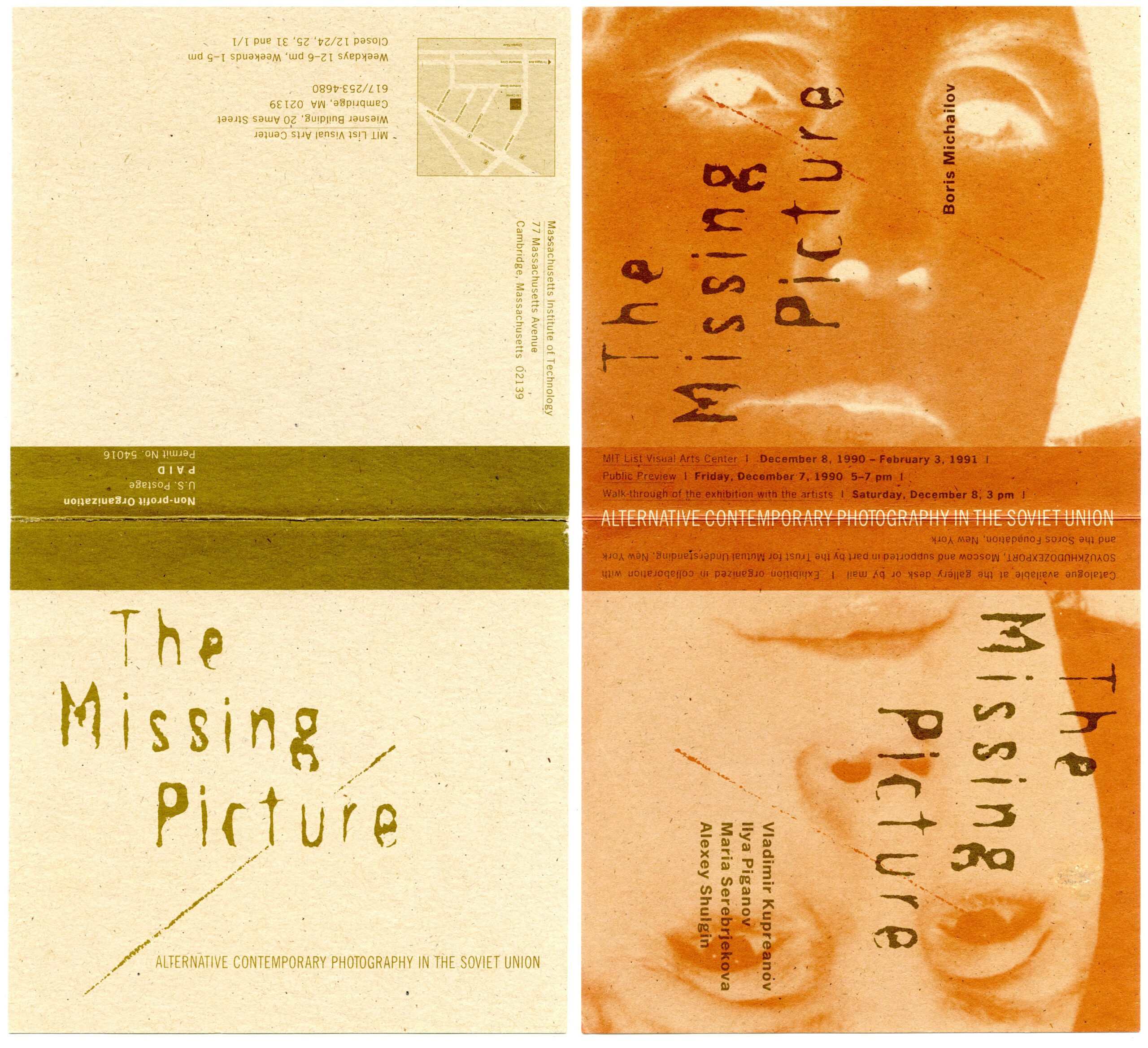

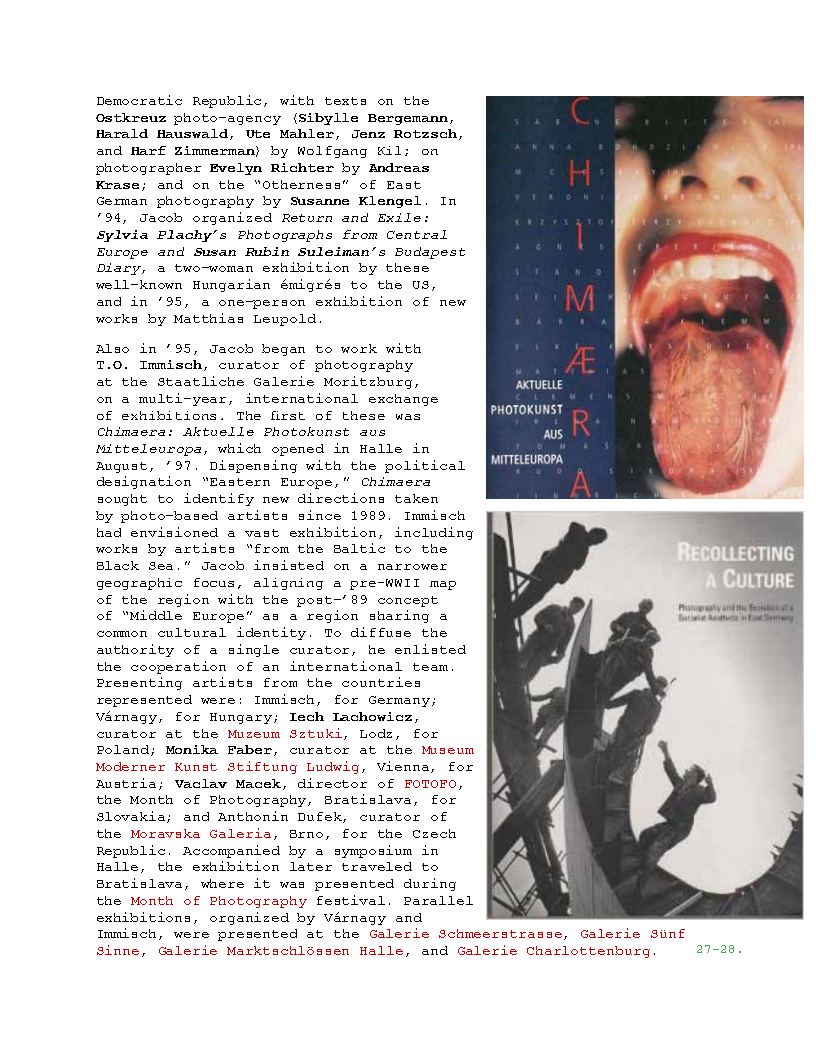

In the US, in 1990 alone, Jacob opened four major exhibitions: Nightmare Works: Tibor Hajas, co-curated with Steven High for the Anderson Art Gallery; Hidden Story: Samizdat from Hungary and Elsewhere, co-curated with Várnagy for the Franklin Furnace; The Missing Picture: Alternative Contemporary Photography in the Soviet Union, a group exhibition for the List Visual Arts Center at MIT; and The Missing Picture: Boris Michailov, a one-person exhibition, also for the LVAC.

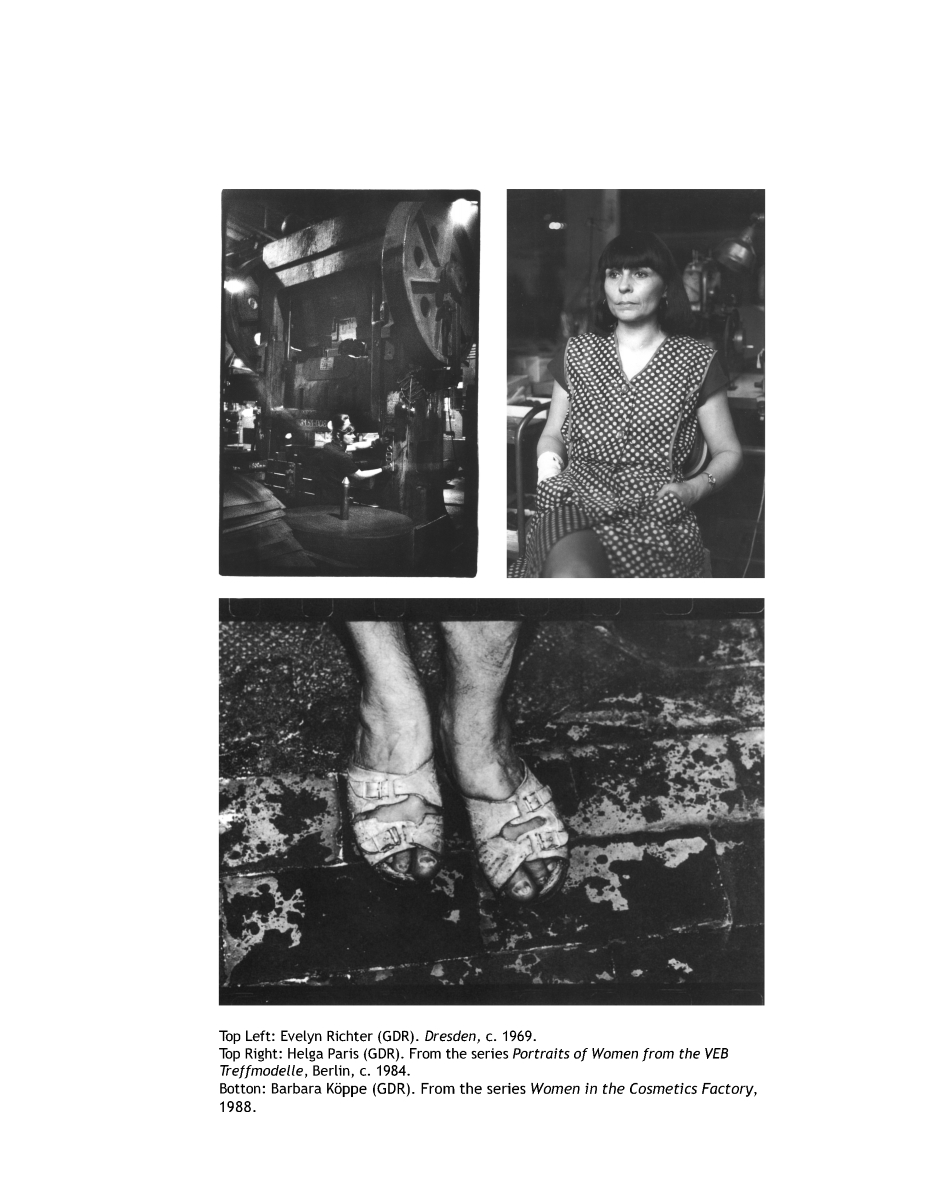

Throughout the 1990s, Jacob continued his cooperation with Várnagy and Sachse. In 1991, in conjunction with the centennial celebration of John Heartfield’s birth, Sachse staged an action and Jacob read a paper for the Akademie der kunst zu Berlin’s international forum on Heartfield, and they co-curated a satellite exhibition, Photomontage Heute, for the Fotogalerie Berlin-Friedrichshain. In 1992, Jacob was hired as Director of Exhibitions for the Photographic Resource Center (PRC) at Boston University. At the PRC, in 1993, he organized an internet-based presentation entitled Out of Control: Photography from East Germany, co-edited with Sachse. Contributors to the project documented the uses of photography in the GDR before and after its collapse. In 1994, Jacob organized Return and Exile: Sylvia Plachy’s Photographs from Central Europe and Susan Rubin Suleiman’s Budapest Diary, a two-woman exhibition by these well-known Hungarian emigres to the US, and in 1995, he presented a one-person exhibition of works by Matthias Leupold. Prospective exhibitions on Hungarian photographers in New York City, and a retrospective of Milan Knizák, failed to gain traction.

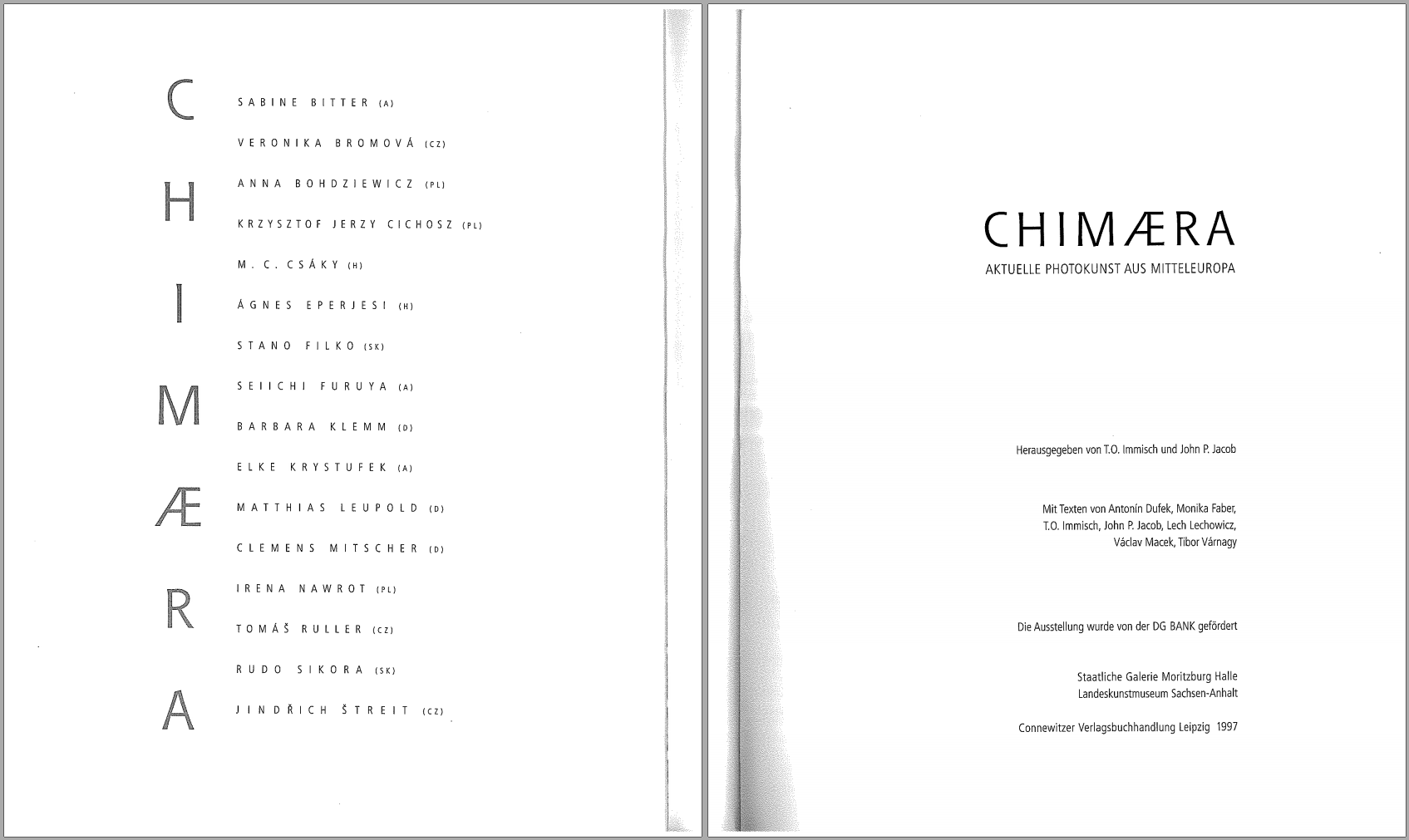

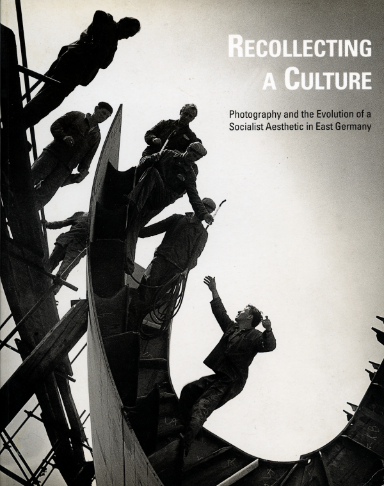

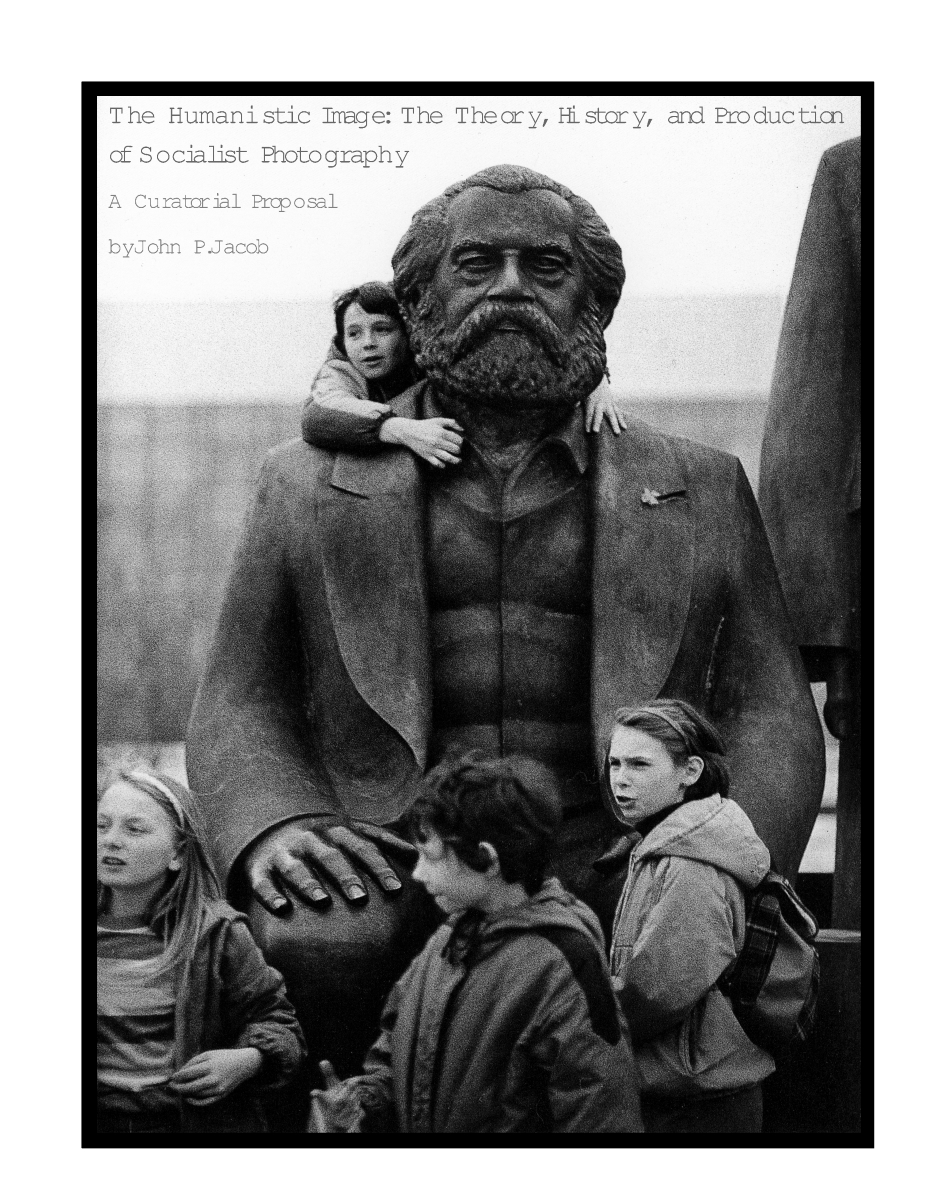

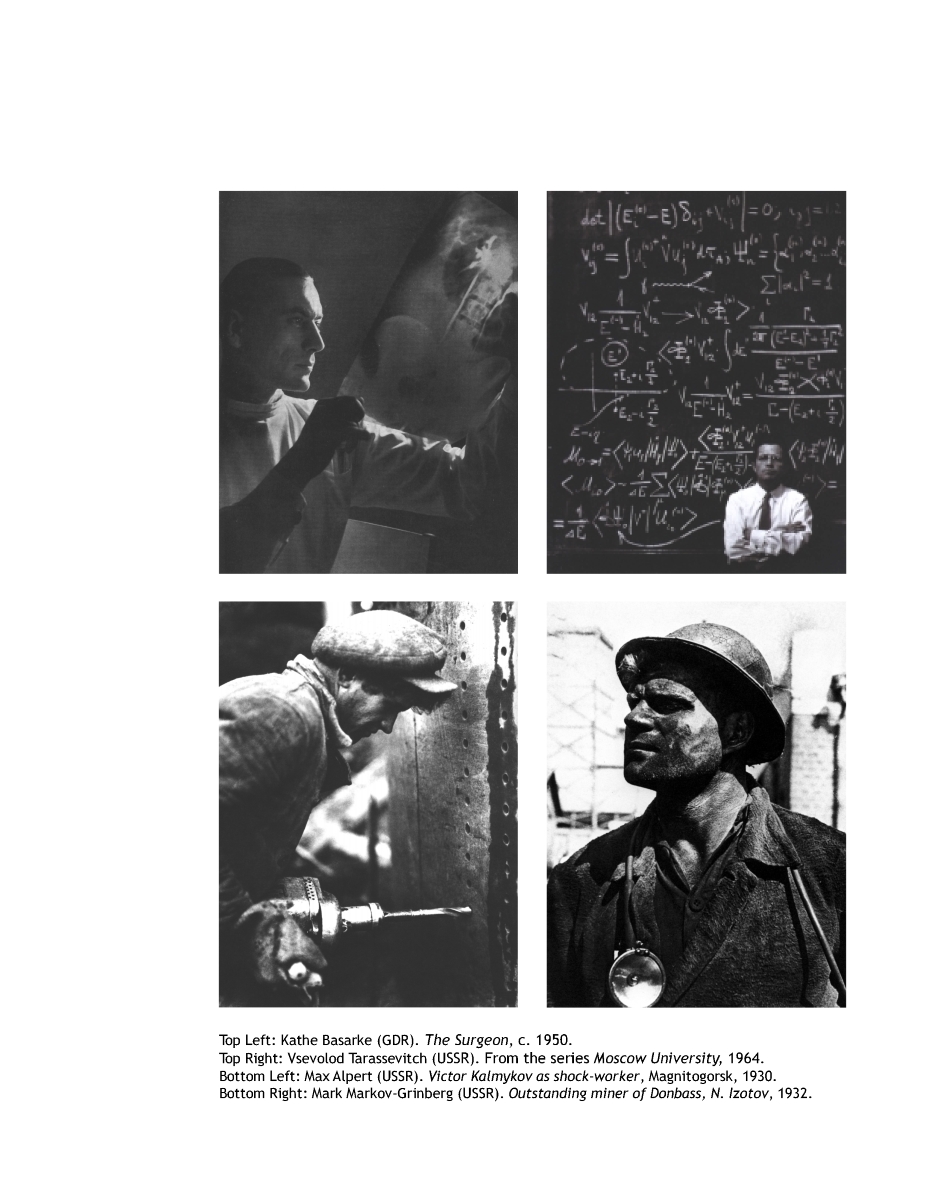

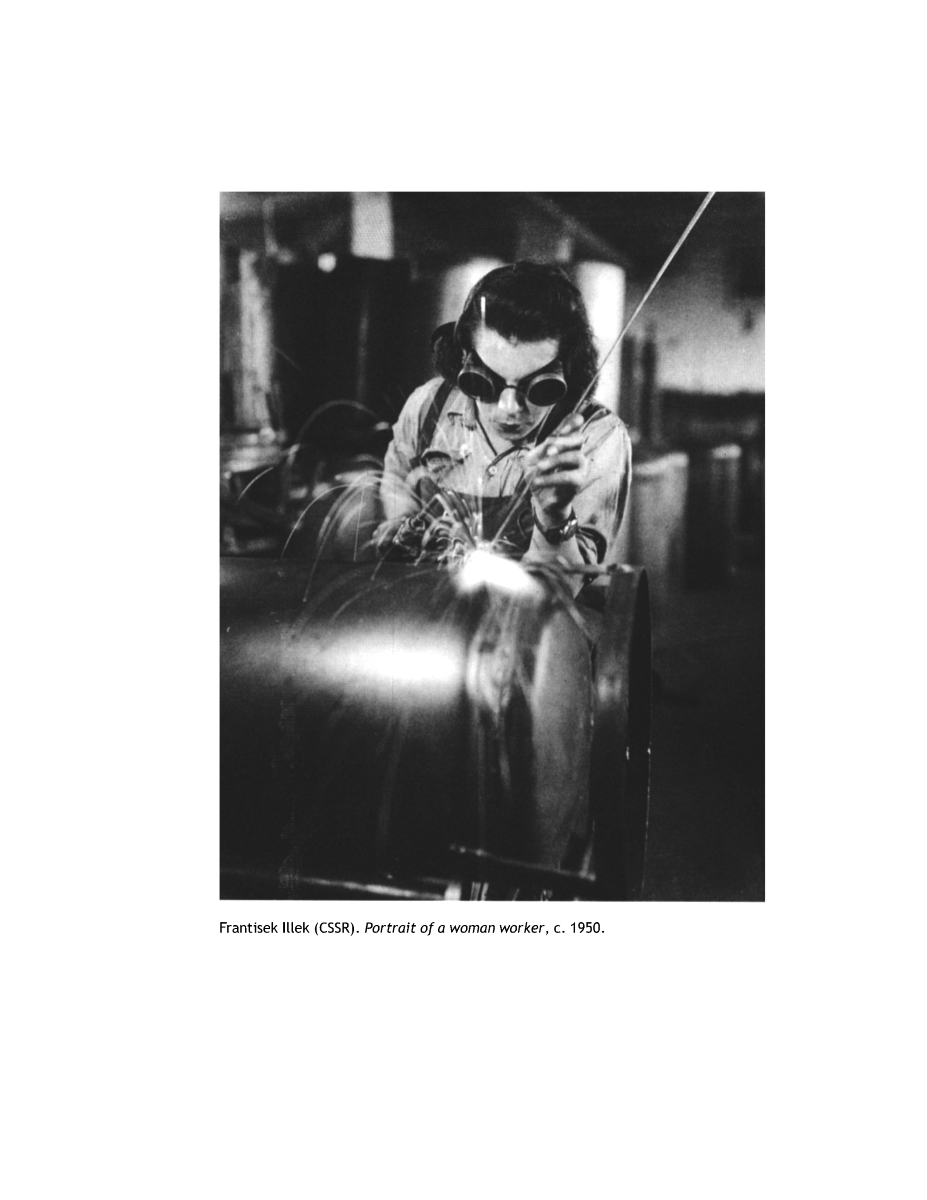

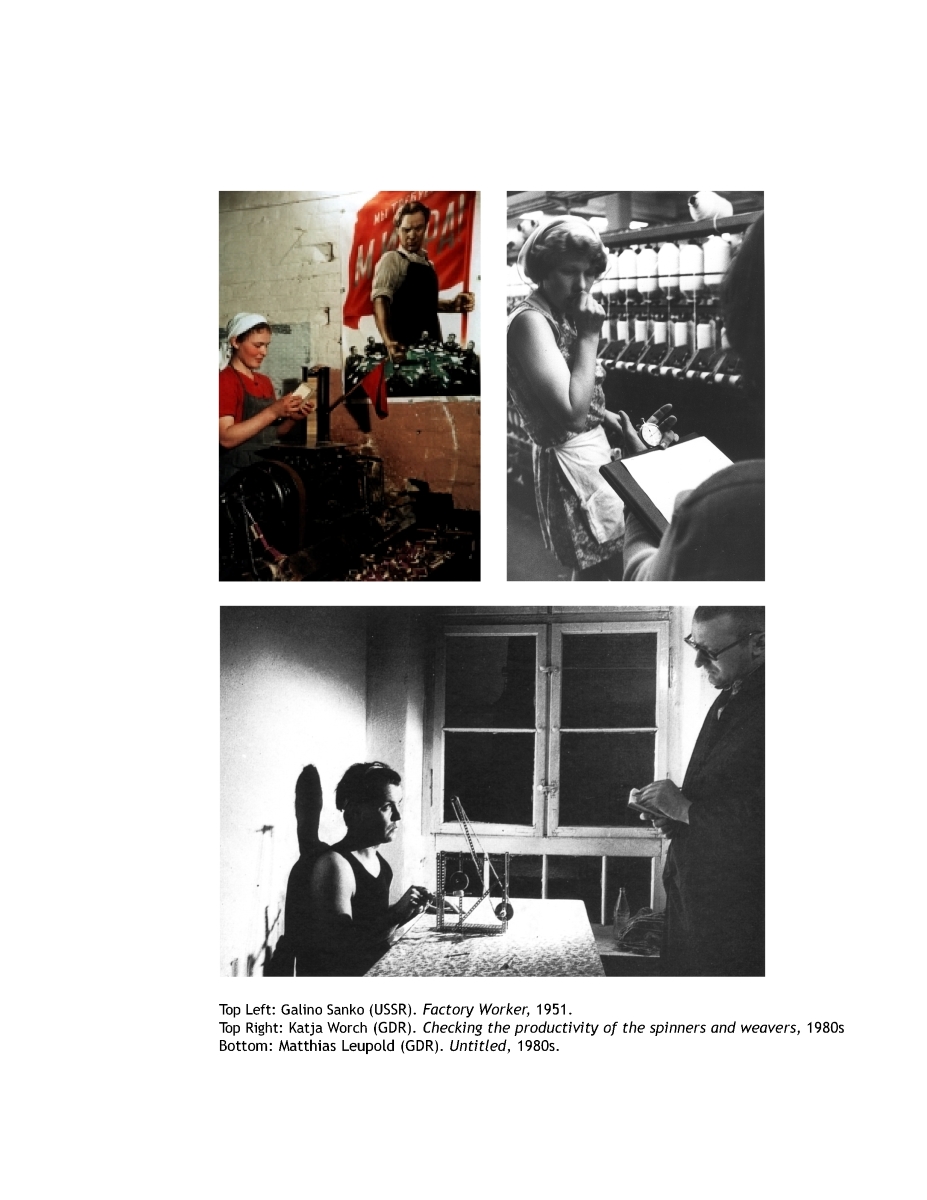

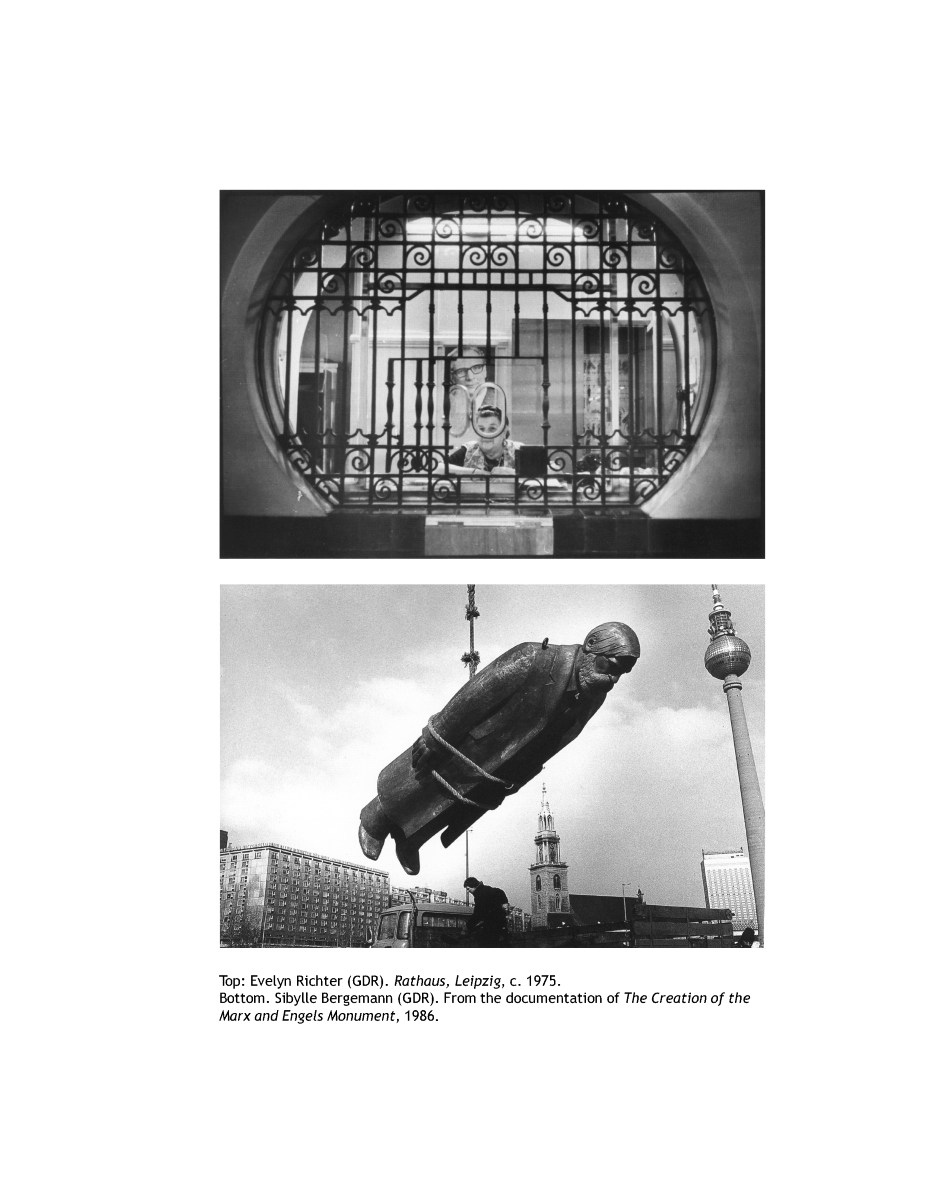

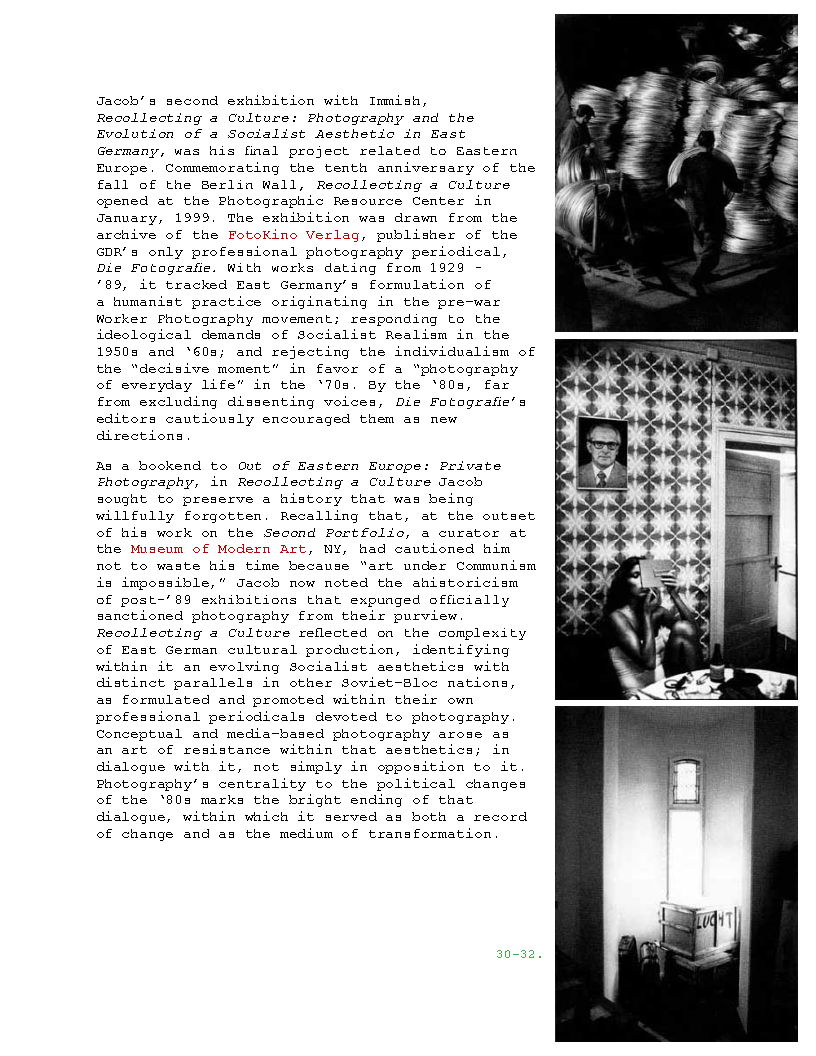

Also in 1990, Jacob began to work with T.O. Immisch, curator of photography at the Staatliche Galerie Moritzburg, Halle, on a multi-year, international exchange of exhibitions. The first of these was Chimaera: Aktuelle Photokunst aus Mitteleuropa, which opened in Halle in August, 1997. Jacob’s second exhibition with Immish, Recollecting a Culture: Photography and the Evolution of a Socialist Aesthetic in East Germany, was his last related to Eastern Europe. Opening at the PRC in 1999, it commemorated the tenth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. In his critical writing from this period, and specifically in Recollecting a Culture, Jacob focused on the ahistoricism of post-1989 books and exhibitions that omitted officially sanctioned photography, considering the reasons for and the impact of such exclusions, including in his own work.

Produce related to Eastern European & Soviet photography, post-1989:

1990

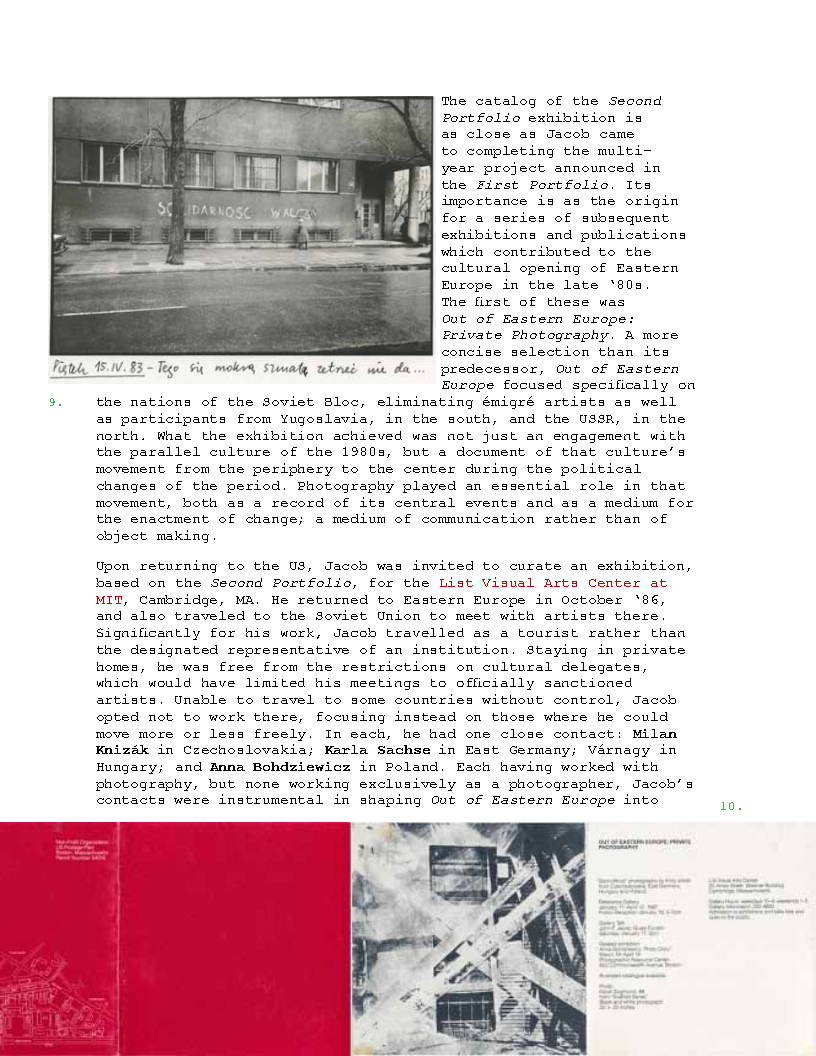

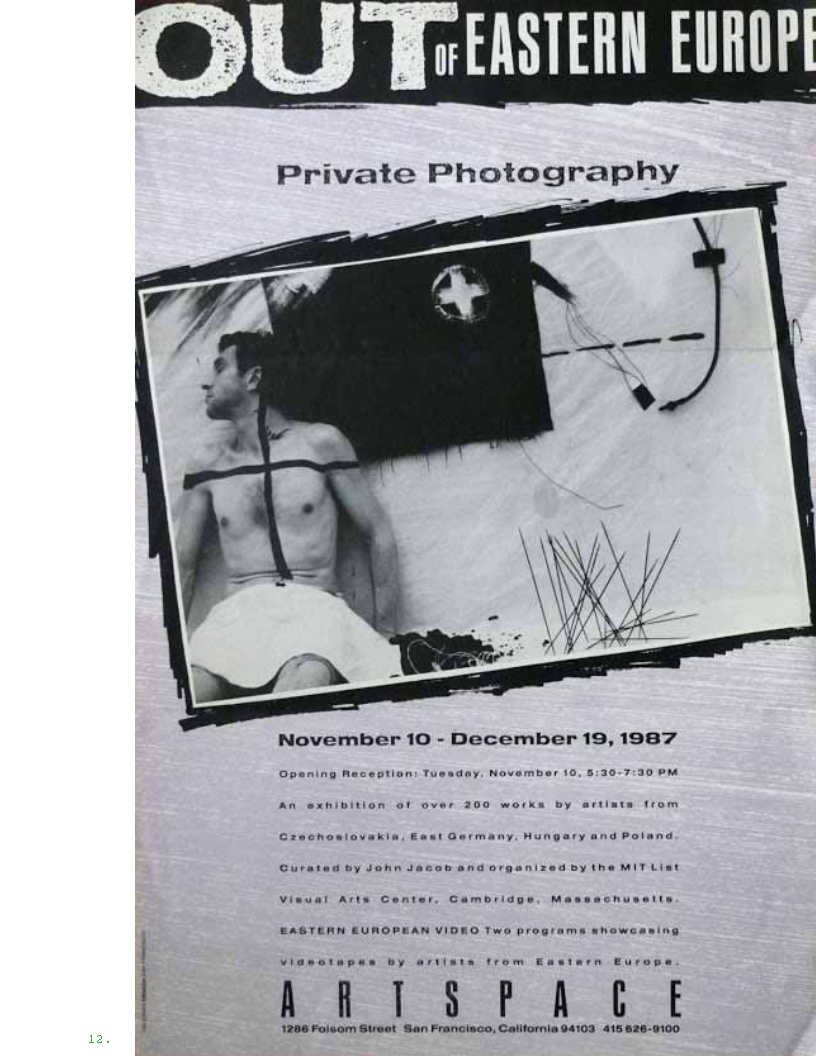

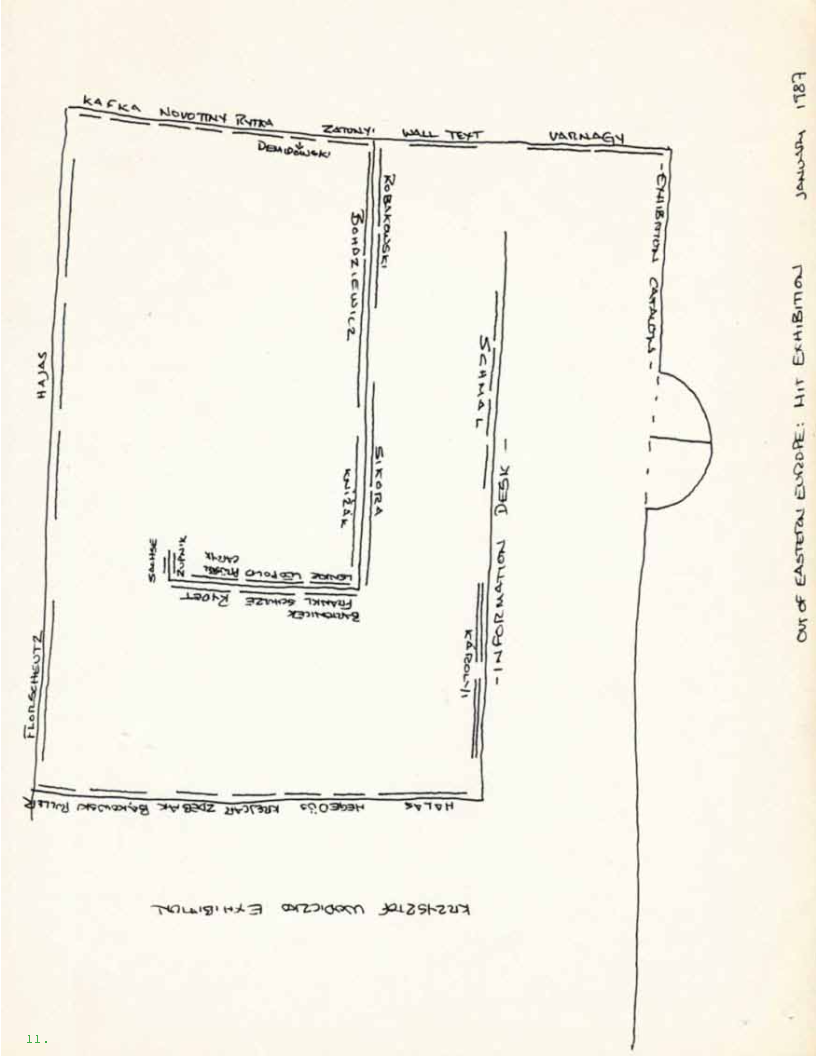

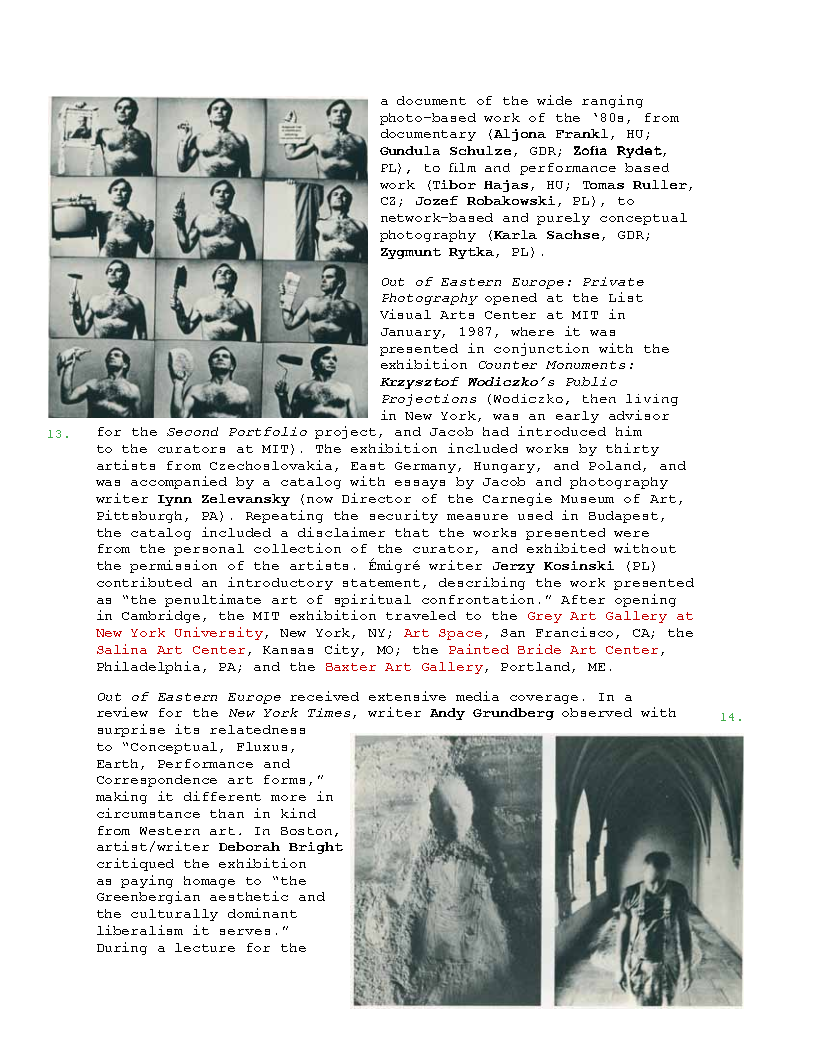

Nightmare Works: Tibor Hajas (exhibition + catalog, with Steven S. High, Anderson Gallery, Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA)

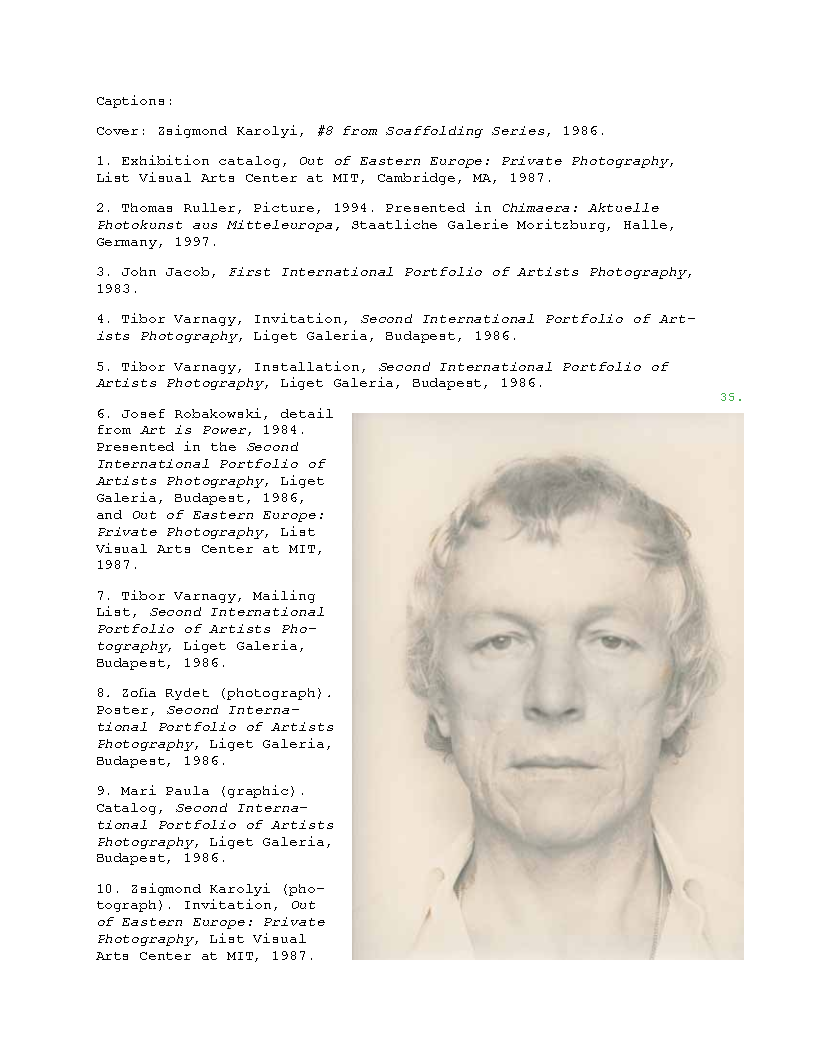

Hidden Story: Samizdat from Hungary and Elsewhere (exhibition + catalog, with Tibor Várnagy, Franklin Furnace, NYC)

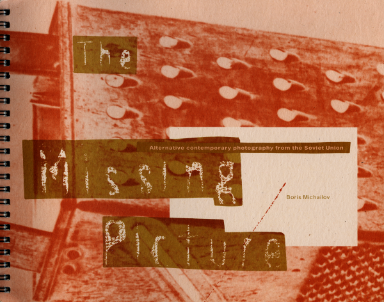

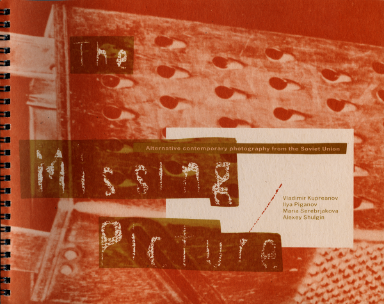

The Missing Picture: Alternative Contemporary Photography from the Soviet Union, Vladimir Kupreanov, Ilya Piganov, Maria Serebrjakova, Alexey Shulgin (exhibition + catalog, List Visual Arts Center at MIT)

The Missing Picture: Boris Mikhailov (exhibition + catalog, List Visual Arts Center at MIT)

1991

Beyond Fascination: Contemporary Eastern European Art in Western Perspective (paper, Milena Kalinovska moderator, College Art Association, Washington, DC)

A Short History of Soviet Photography (lecture, Washington University, St. Louis, MO)

“Perspectives, Real & Imaginary: Czechoslovakian Photography at FotoFest” (essay, Spot, Houston Center for Photography, Winter)

Photomontage Heute (exhibition, with Karla Sachse, Fotogalerie Berlin-Friedrichshain, Berlin)

Montage als Kunstprinzip: Colloquium zur John Heartfield (conference participant, Akademie der Kunst in Berlin, Germany)

“Reality and History: Observations for John Heartfield” (paper, Akademie der kunst in Berlin)

1993

Photo/Foto: Russian Art Photography Today Symposium (panelist and moderator, Diane Neumaier organizer, State University of New Jersey at Rutgers)

“Recollecting a Culture: East Germany and Photojournalism” (paper, Vicki Goldberg moderator, College Art Association, Seattle, WA)

“Out of Control: Photography from East Germany” (online anthology, with Karla Sachse, Photographic Resource Center, Boston, MA)

“Photoglyphs” (catalog essay for Photoglyphs: Rimma and Valeriy Gerlovin, Mark Sloan curator, New Orleans Museum of Art, LA)

1994

Return and Exile: Sylvia Plachy’s Photographs from Central Europe and Susan Rubin Suleiman’s Budapest Diary (exhibition, Photographic Resource Center, Boston, MA)

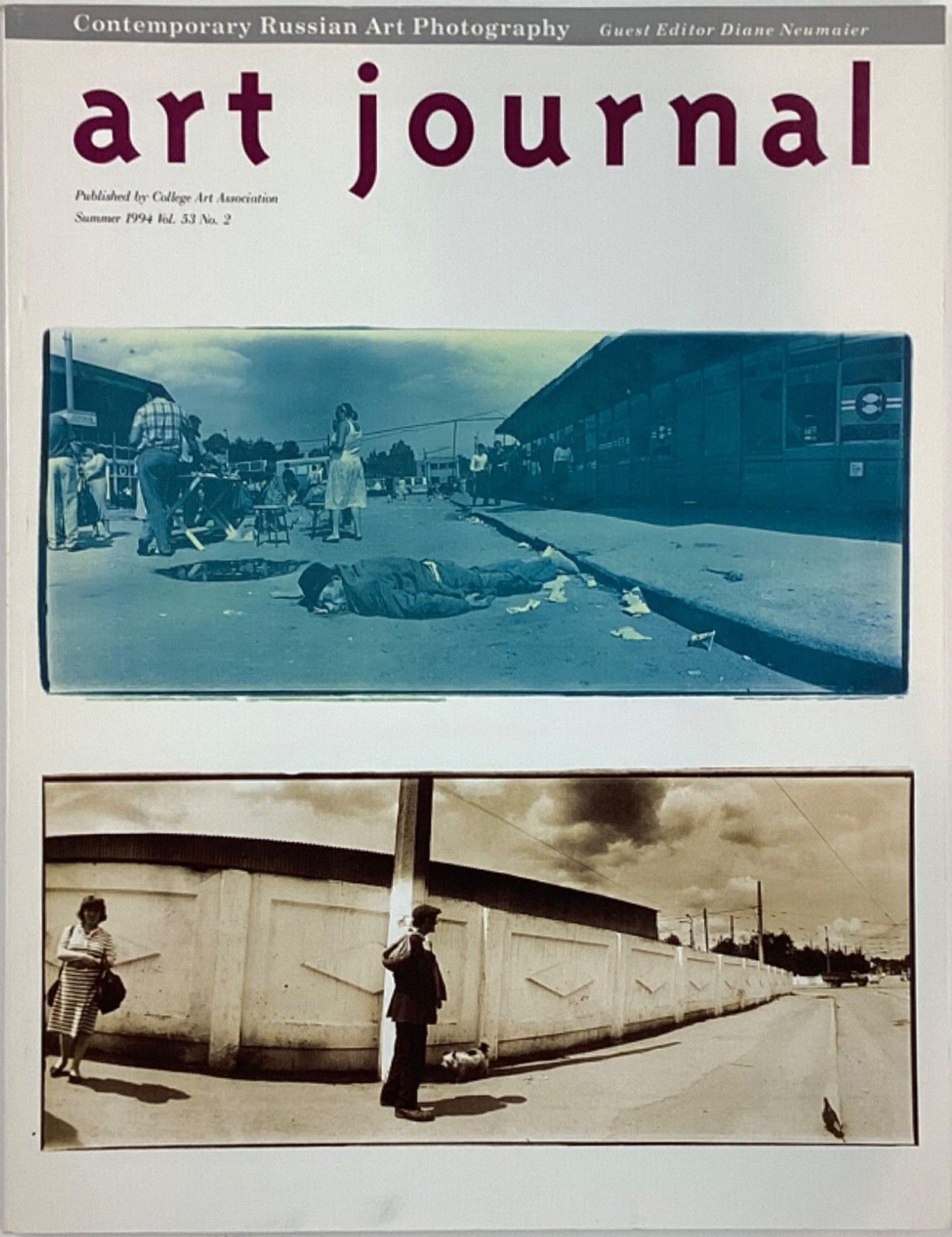

“After Roskolnikov: Russian Photography Today” (essay, Art Journal, Summer 1994 53 (2))

“Samizdat in 1989: Closing the Book” (essay, Liget Galeria Almanack: Central European Art in the Late ’80s, Tibor Várnagy ed., Liget Galeria, Budapest)

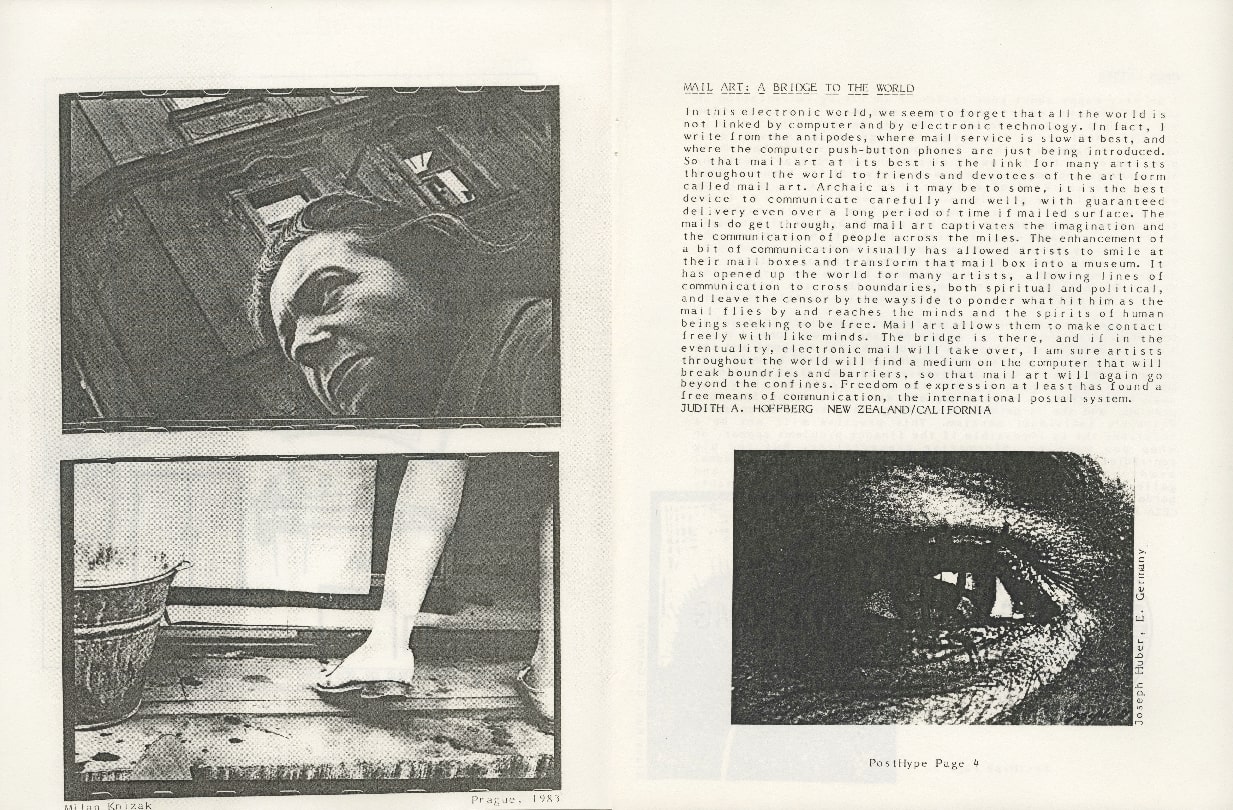

“Aesthetic Revolution or Personal Evolution?” (essay, Eternal Network: A Mailart Anthology, Chuck Welch ed., University of Calgary Press, Canada)

1995

Matthias Leupold: Fahnenappell & Gartenlaube (exhibition, Photographic Resource Center at Boston University)

1996

“Introduction” (catalog essay for Matthias Leupold: Living Pictures 1983-1995, Stipendiat im Künstlerdorf Schöppingen, Germany)

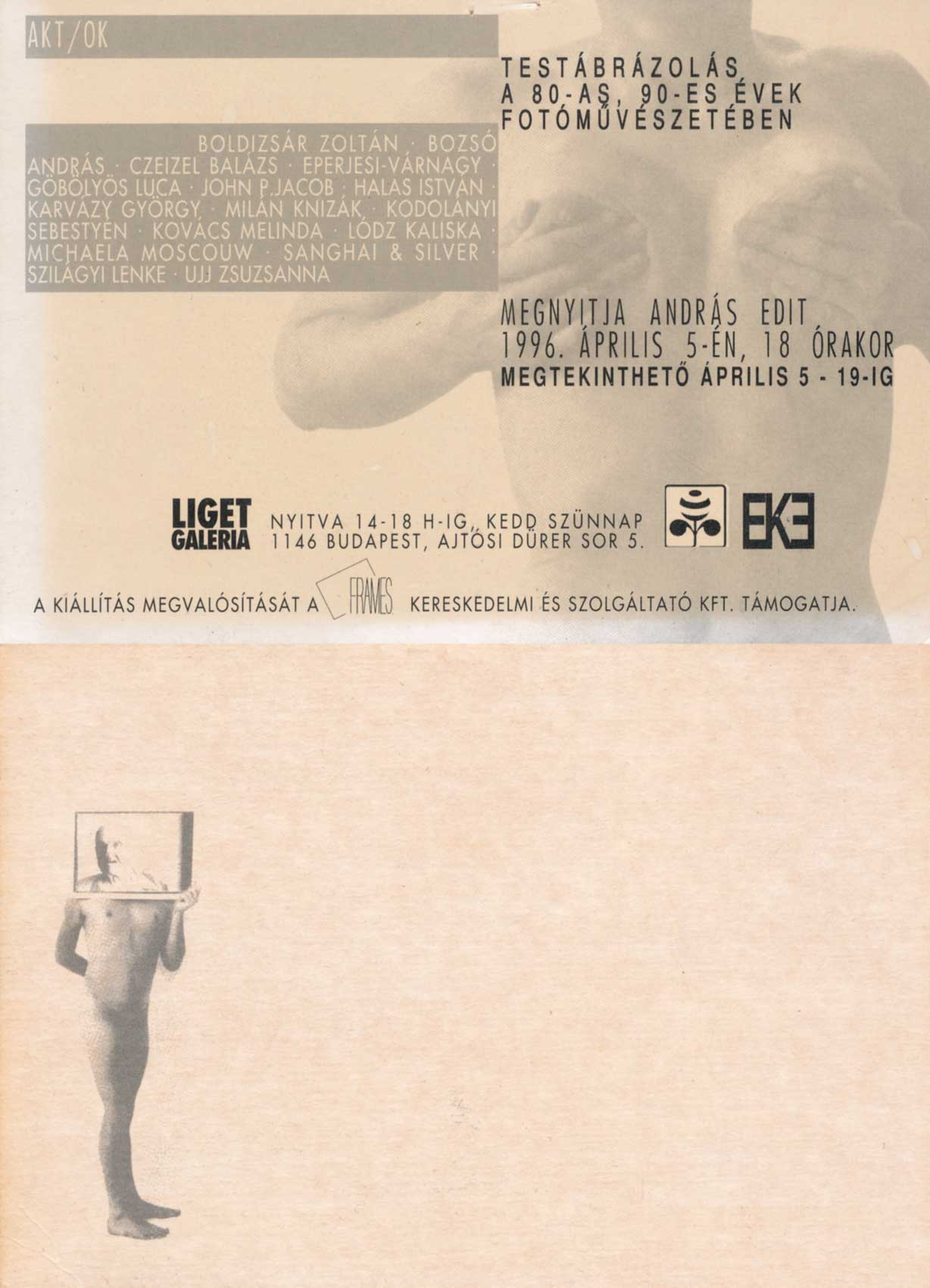

AKT/ok (group exhibition incl. Jacob, Liget Galeria, Budapest)

1997

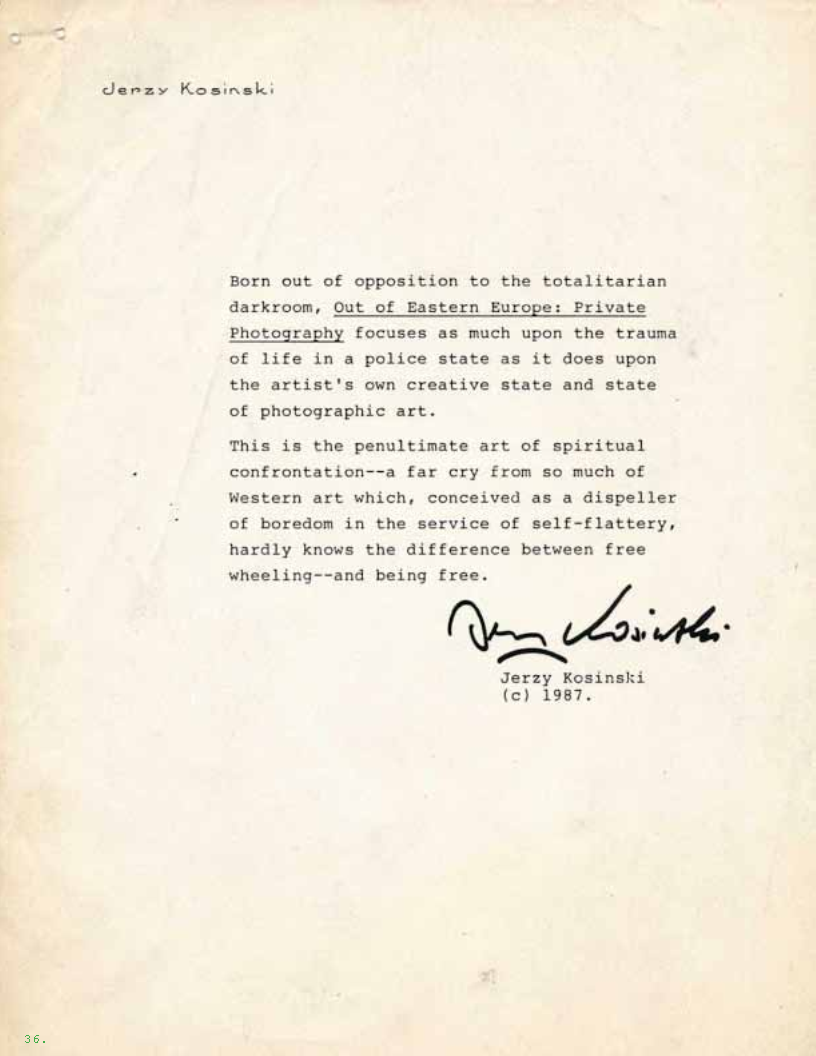

Chimaera: Aktuelle Photokunst aus Mitteleruopa (exhibition + catalog, with Tony Dufek, Monika Faber, TO Immisch, Lech Lechowicz, Vaclav Macek, and Tibor Várnagy, Staatliche Galerie Moritzburg Halle)

Ex Oriente: Contemporary Photography from Central Europe (conference co-coordinator, with TO Immisch, Staatliche Galerie Moritzburg Halle, Germany)

1998

East/West Dialogue: Contemporary Art in Eastern Europe (conference participant, Rhode Island School of Design Museum, Providence, RI)

1999

Recollecting a Culture: Photography and the Evolution of a Socialist Aesthetic in East Germany (exhibition + catalog, Photographic Resource Center at Boston University)

2000

Recollecting a Culture: Photography and the Evolution of a Socialist Aesthetic in East Germany

The exhibition traveled to the Hampshire College Gallery, Amherst, MA, hosted by Robert Seydel (exhibition + lecture)

2002

Symposium on Photographic Archives in the Former GDR (conference participant, Staatliche Galerie Moritzburg Halle, Germany)

2017

The First International Portfolio of Artists Photography 35th Anniversary (exhibition, with Tibor Várnagy and Robert Swierkeiwicz, Liget Galeria, Budapest)

2019

“Time Travel with Tibor Várnagy” (catalog essay for Várnagy Tibor: Photos without Camera, 1985–1993, ACB Research Lab, Budapest, Hungary)

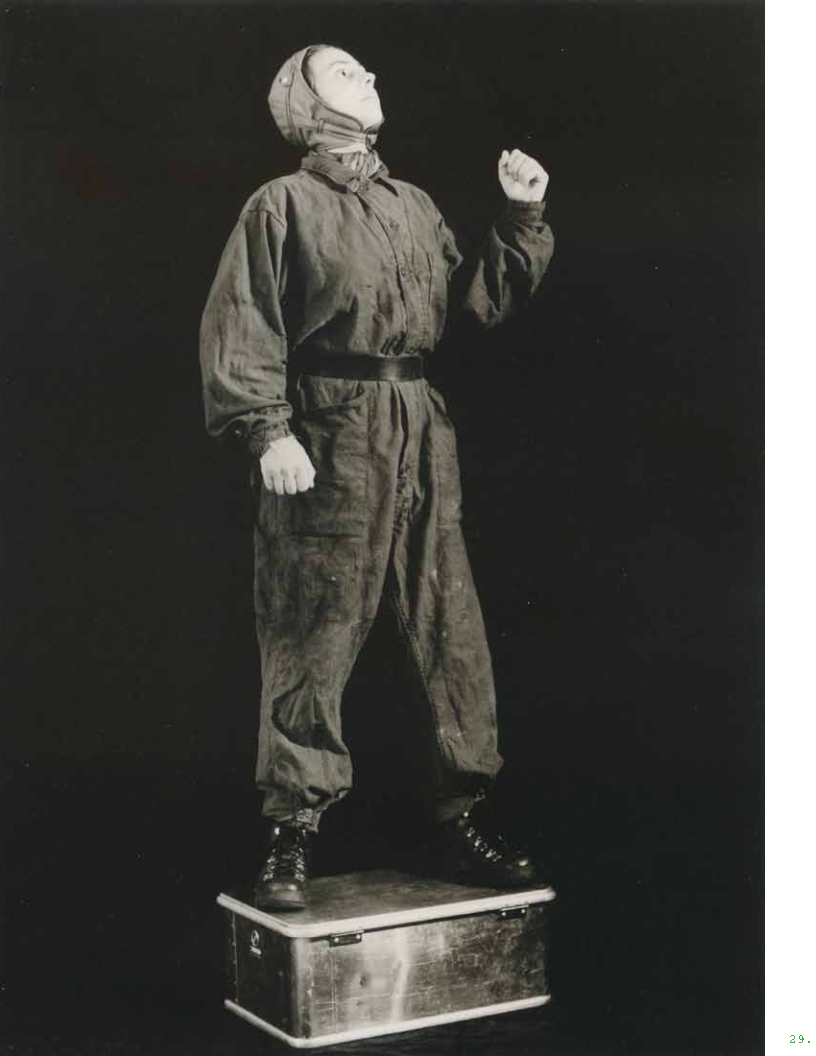

Nightmare Works: Tibor Hajas

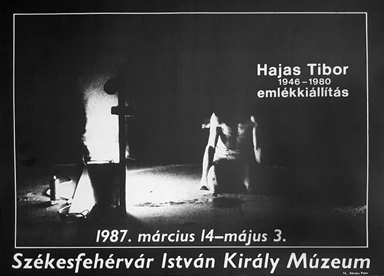

The press release for the exhibition Tibor Hajas: Emergency Landing, presented by the Ludwig Museum, Budapest, in 2005, noted that “The works of Tibor Hajas… were previously presented on three occasions, with exhibitions at the King Saint Stephen Museum, Székesfehérvár, in 1987; the Anderson Gallery, Richmond (USA), in 1990; and a Commemorative Exhibition held at the Ernst Museum, Budapest, in 1997.”

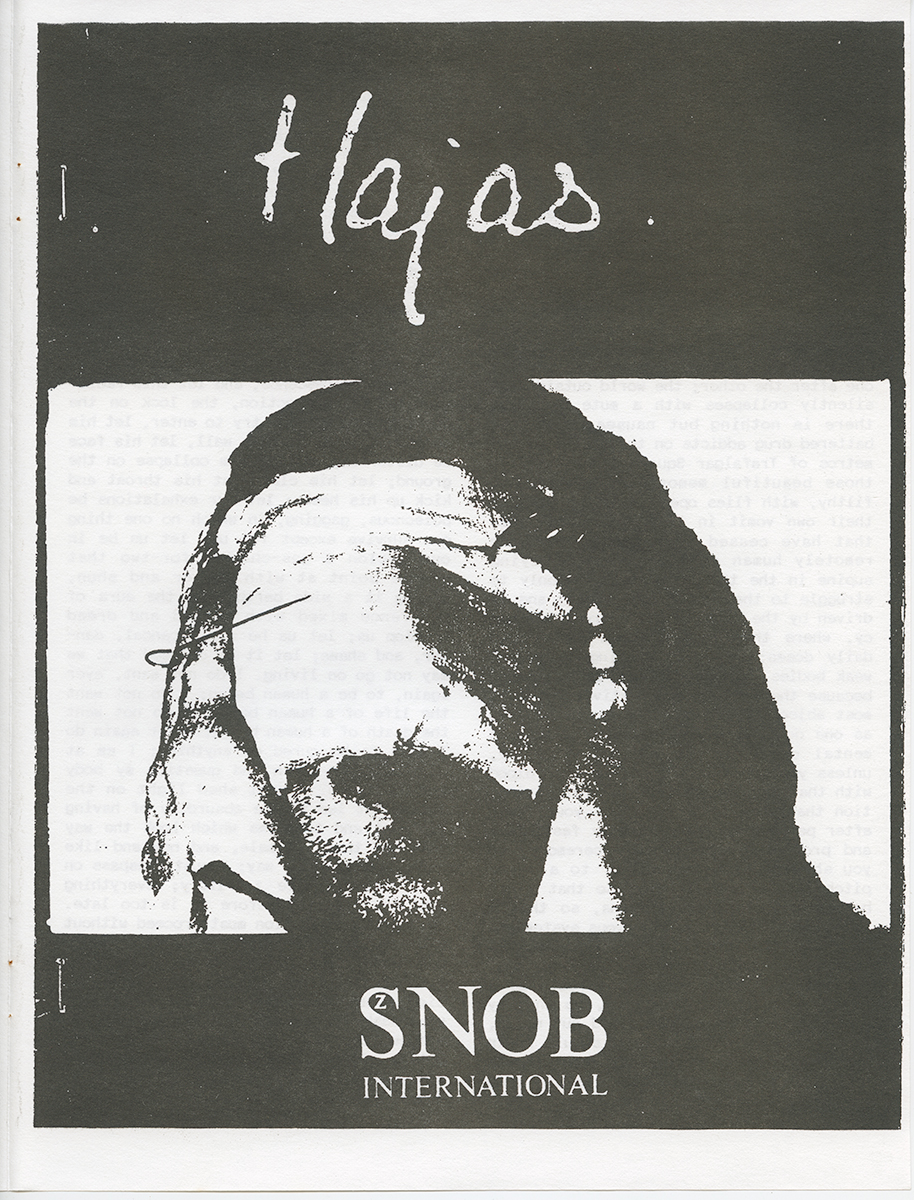

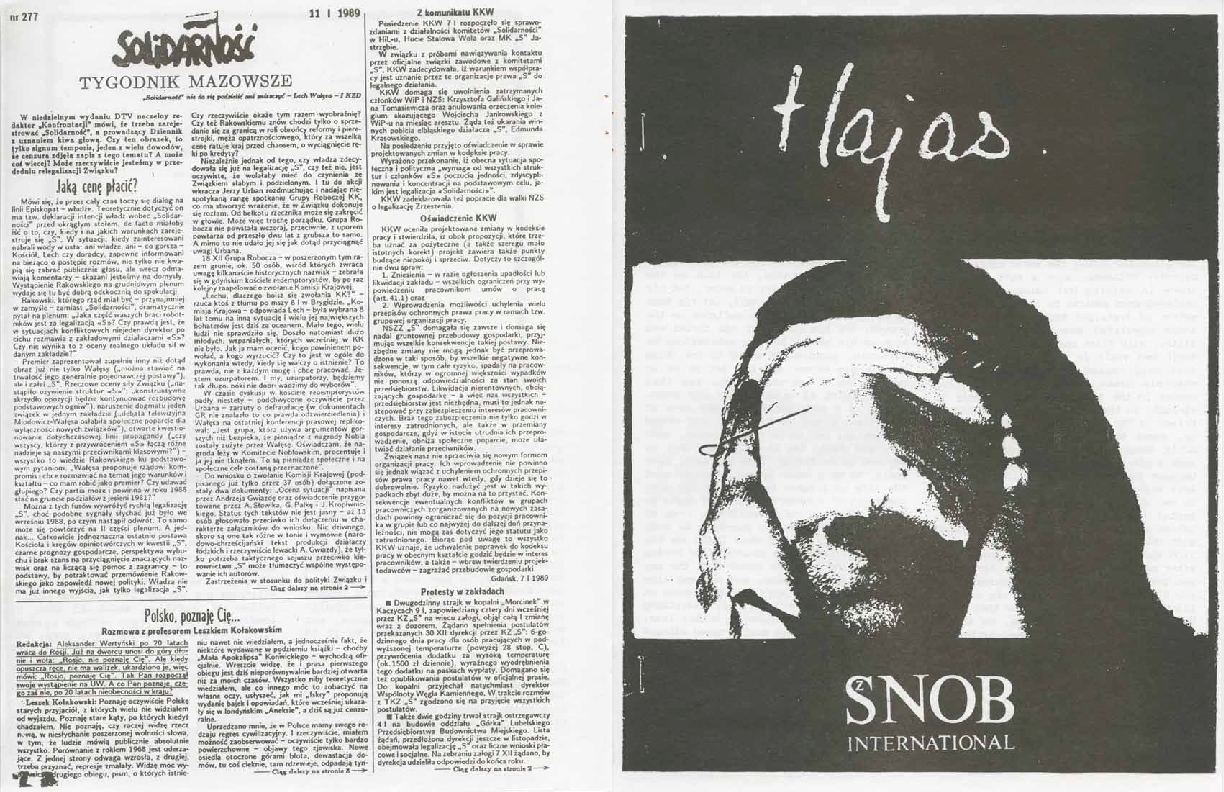

The chronology is not accurate. In 1986, a small selection of works by Hajas was presented at the Liget Galeria, when Várnagy organized an exhibition of the Hungarian photographers under consideration for Out of Eastern Europe: Private Photography. Jacob transported Hajas’ photographs to the US, and they were exhibited at the List Visual Arts Center at MIT, in 1987. Hajas was also presented in the exhibition Zeitgenossische Ungarische Fotografie, curated by Dr. Gerlinde Schrammel, at the Liget Galeria and the Fotogalerie Wien in 1988, to which Jacob contributed a catalog essay. Finally, in 1990, the fourth issue of the underground journal Sznob International, dedicated to Hajas’s work, was presented by Várnagy and Jacob in Hidden Story: Samizdat from Hungary and Elsewhere. Several pages of the journal were reproduced in the exhibition catalog.

Hajas was a “forbidden” artist in the 1970s and 1980s. These smaller representations of his work, at home and abroad, were instrumental to his reformation. They took the political temperature for larger Hungarian institutions that were wary of censure by the cultural ministries. Jacob later wrote:

“Censorship,” as writer Miklós Haraszti has noted, “is the final glaze that the state applies to the work of art before approving its release to the public.” Tibor Hajas was “rehabilitated” in 1986, six years after his death, when a small selection of his works exhibited at the Liget Galeria in Budapest failed to arouse official indignation. Following the lead of the Liget, the István Király Múzeum in Székesfehérvár opened a retrospective “memorial exhibition” for Hajas in early 1987. The exhibition Hungarian Art of the Twentieth Century, The End of the Avant-Garde, presented at the István Király Múzeum in 1989, nine years after Hajas’ death, was among the first to present his work within the larger context of the Hungarian avant-garde.

Jacob was introduced to Hajas’s work by Várnagy. Várnagy also introduced Jacob to János Vető, an artist and musician who collaborated with Hajas, documenting and making sequential artworks of his performances; to László Beke, who, from the late 1960s, was a catalyst for art networks and cross-border collaborations in and beyond Eastern Europe, and was Hajas’ most vocal advocate; and to György Széphelyi, Hajas’ brother. Várnagy and Jacob secured the approval by Széphelyi for the use of Hajas’ work in Out of Eastern Europe, and Jacob was given several original panels by Hajas and Vető as well as several sequences printed by Várnagy from Vető’s negatives, including lesser known ones such as Lou Reed Total (1979). At that time, Jacob also spoke with Beke and Széphelyi about a one-person exhibition in the US. They agreed to it once a retrospective had been presented in Hungary. The ideal of an exhibition at the Műcsarnok in Budapest, where Beke worked, was still politically impossible, so it opened at the István Király Múzeum. After the exhibition in Székesfehérvár, in 1987, Jacob began work in earnest on a Hajas exhibition in the US.

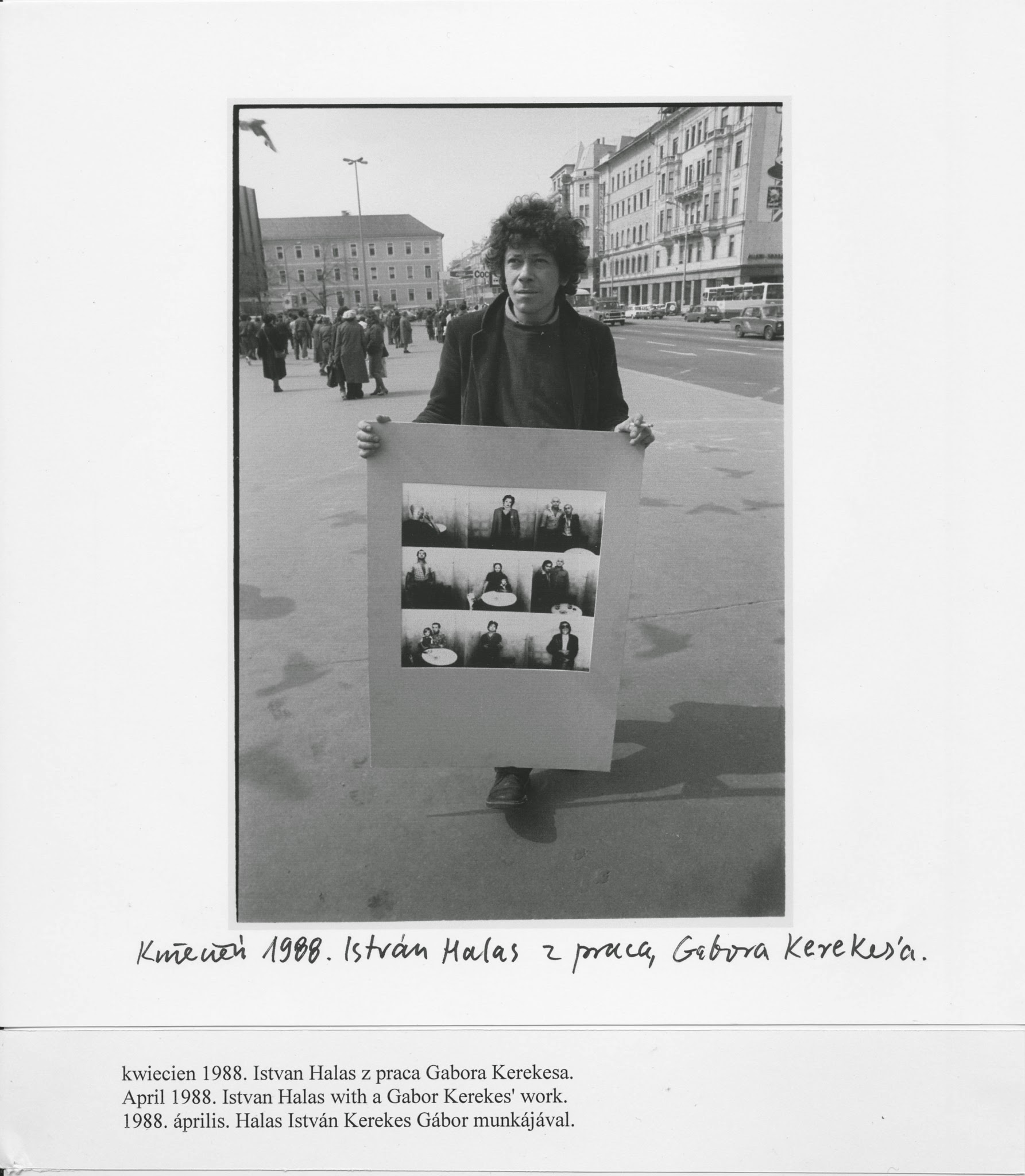

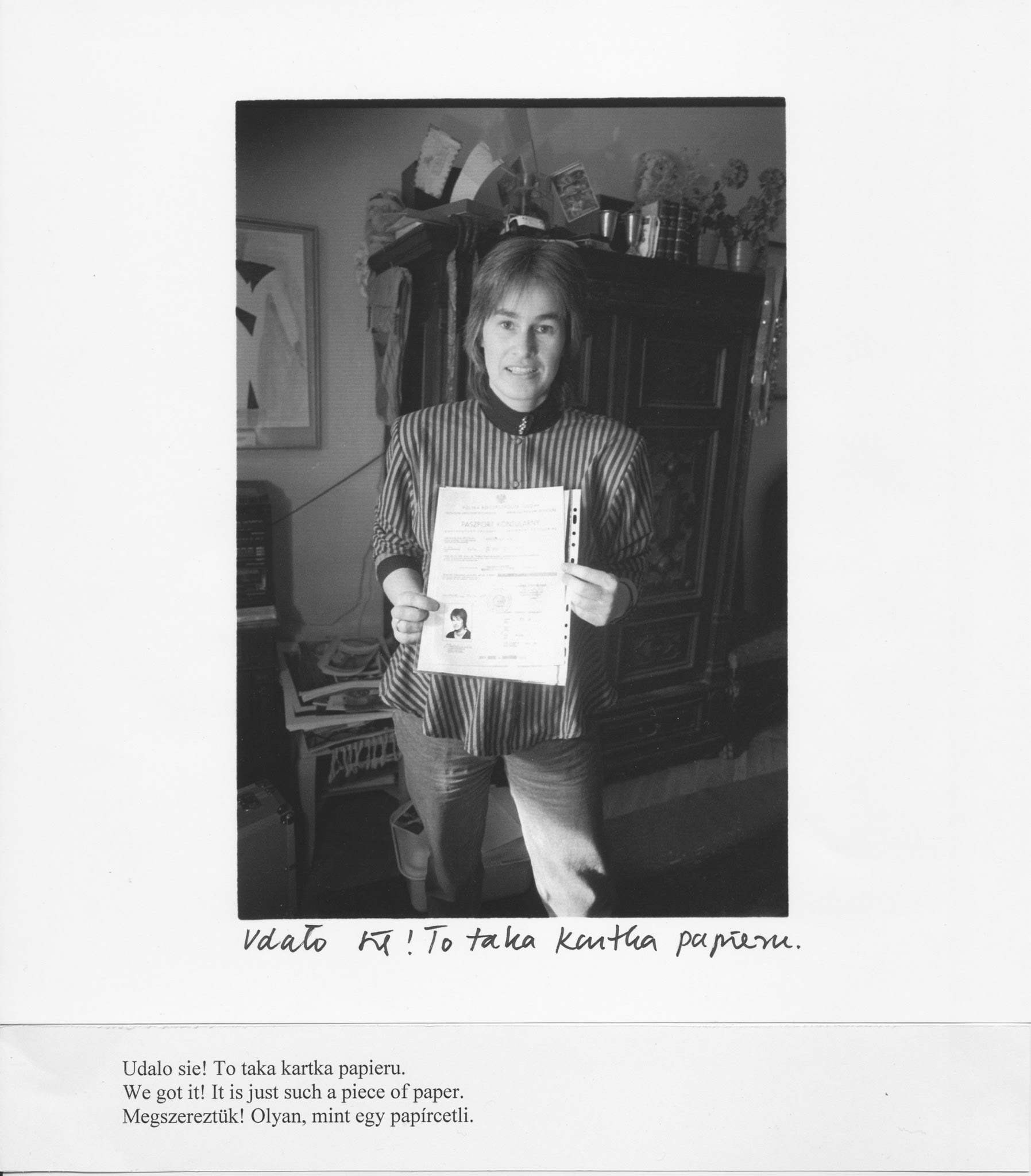

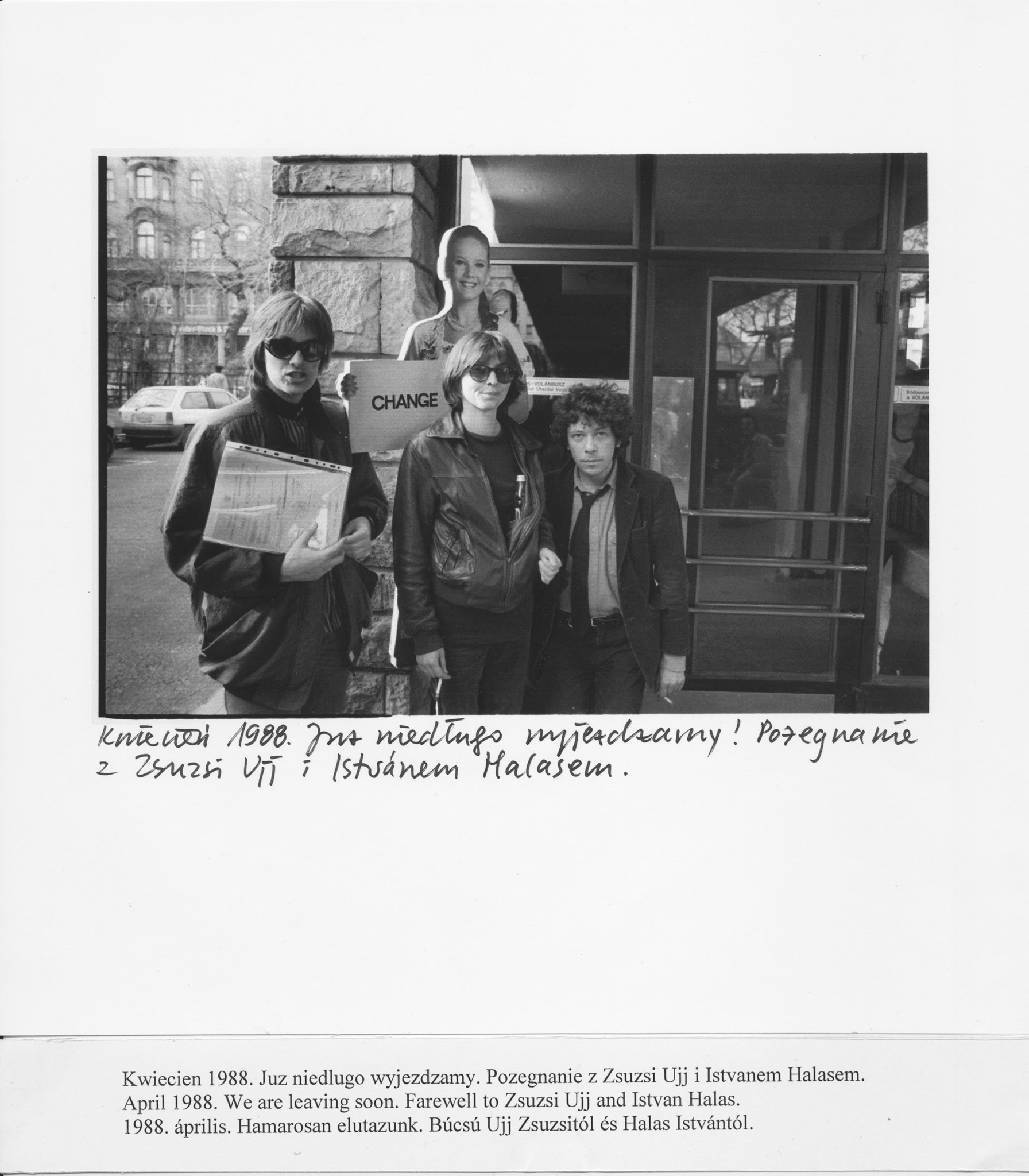

Steven High seemed like an ideal partner. He was director of the Maine College of Art Gallery when Out of Eastern Europe travelled to Portland, ME, in 1988, and he invited Jacob to present a satellite exhibition, Leupold/Leupold: Staged Photographs. After he moved on to the Anderson Gallery at Commonwealth University in Richmond, VA, Jacob worked with him on a one-person exhibition by Thomas Flotscheutz, contributing a catalog essay. Jacob approached High about co-curating the Hajas exhibition. They traveled to Budapest together, and Jacob and Várnagy introduced him to Beke and Széphelyi. The selection process was easy; they took everything that was available directly from the Hajas estate. Shipping was handled by the Soros Foundation’s Documentation Center, which also translated and shared its research on Hajas, a crucial addition to the catalog. István Halas was hired to photograph the artworks for the catalog, and Várnagy printed performance documentation from Vető’s negatives for the installation. Beke and Jacob contributed catalog texts, and Jacob consulted with High on the title, the catalog, and the installation design. Nevertheless, when Jacob received a draft of the catalog, he was not credited as co-curator. High made excuses blaming his institution. It would be the last time Jacob worked with him.

Despite Jacob’s disappointment with High, the exhibition was thoughtfully installed and the catalog was both informative and beautifully designed. In particular, Jacob’s essay marked a turning point in his critical writing. Jacob had been unsure how to meaningfully explain work such as Hajas’ to a non-specialist American audience. For earlier exhibitions, he developed an interpretive method that combined art historical reference and current events. Looking at Hungarian photographers in The Metamorphic Medium, for example, reference to André Kertész or László Moholy-Nagy situated their work in the art historical past of international modernism, while discussion of the cultural imperatives of the János Kádár regime situated them in the geopolitical present. The familiar figures of modernism connected Hungarian photographers and American audiences with a common past. The unfamiliar but potentially legible signs of the political and economic constraints shaping their work in the present offered another key to their practices.

Jacob came to see that focusing on what was common and familiar to American audiences obscured the semantic complexity of Eastern European and Soviet photography, as utterly contemporary and distinctly postmodern. Conceptual and media-based photography arose in Eastern Europe and the USSR as an art of resistance within an evolving socialist aesthetics. It arose in dialogue with that aesthetics, not only in opposition to it. It evolved with parallels from one Soviet-bloc nation to the next, and with differences related to both the unique constraints experienced by artists in one nation or another, and to their distinct photographic histories, such as Germany’s history of worker photography. Artists were not immune to historical influence or influence from abroad, in other words, but that was not what defined their practices. Western critical writing, including by Jacob, elided the dialogue with socialist aesthetics because of its link to Socialist Realism, favoring instead a validating link to international modernism. That is why Sots Art, an ironic Soviet Pop Art that dismissed Socialist Realism as kitsch, succeeded in the post-1989 international marketplace where others failed. Jacob’s essay for Nightmare Works was the first in which he sought to address this interpretive inaccuracy.

He did so by writing of the image as a text under state control. He argued that, in authoritarian regimes, the state claims authorship of all texts. Authorized images may therefore be understood only through the closed or ideological text of state control. Unauthorized images operate differently. Images emerging from totalitarianism, yet unauthorized by the state, are indeterminate; they possess no fixed meaning. In the hands of an artist like Hajas, the open text of the unauthorized image transforms the viewer of the artwork into its author by forcing her to action. “Hajas’ performances challenged audiences against the danger of moral and intellectual passivity,” Jacob wrote. As examples, Jacob first cited and then dismissed any parallels between Hajas’ work and Western artists, such as Hermann Nitsch or Chris Burden, which operate by a different set of rules. He then turned resolutely local, to the work of Hungarian neo-avant-gardist Miklós Erdélyi.

This was a sign of Jacob’s growing familiarity with his subject, of course, but it was also a strategic turn. Rather than historicize Hajas in relation to the past or the West, Jacob flipped the script of his earlier texts, looking forward to Hajas’ influence on photographers of the next generation, notably Vető, Várnagy, and Ujj. Jacob followed this textual strategy for Nightmare Works in his curatorial strategy for another exhibition, The Missing Picture: Alternative Contemporary Photography from the Soviet Union. There, rather than a simple survey of Soviet photography, he presented a group of young Soviet artists influenced by Ukrainian photographer Boris Michailov, then little known outside the USSR. Jacob also returned to Erdélyi’s work many years later, when writing about Várnagy’s cameraless photography.

Nightmare Works: Tibor Hajas (Open/Download PDF)

August 30 – October 14, 1990

Anderson Gallery, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA

Contributors:

Hajas Tibor & Vető János

Texts: Steven High, László Beke, and JP Jacob

Recalling Hajas

John P. Jacob, Austin, 1990

I am he who, in order to be, must whip his innateness.

— Antonin Artaud

1.

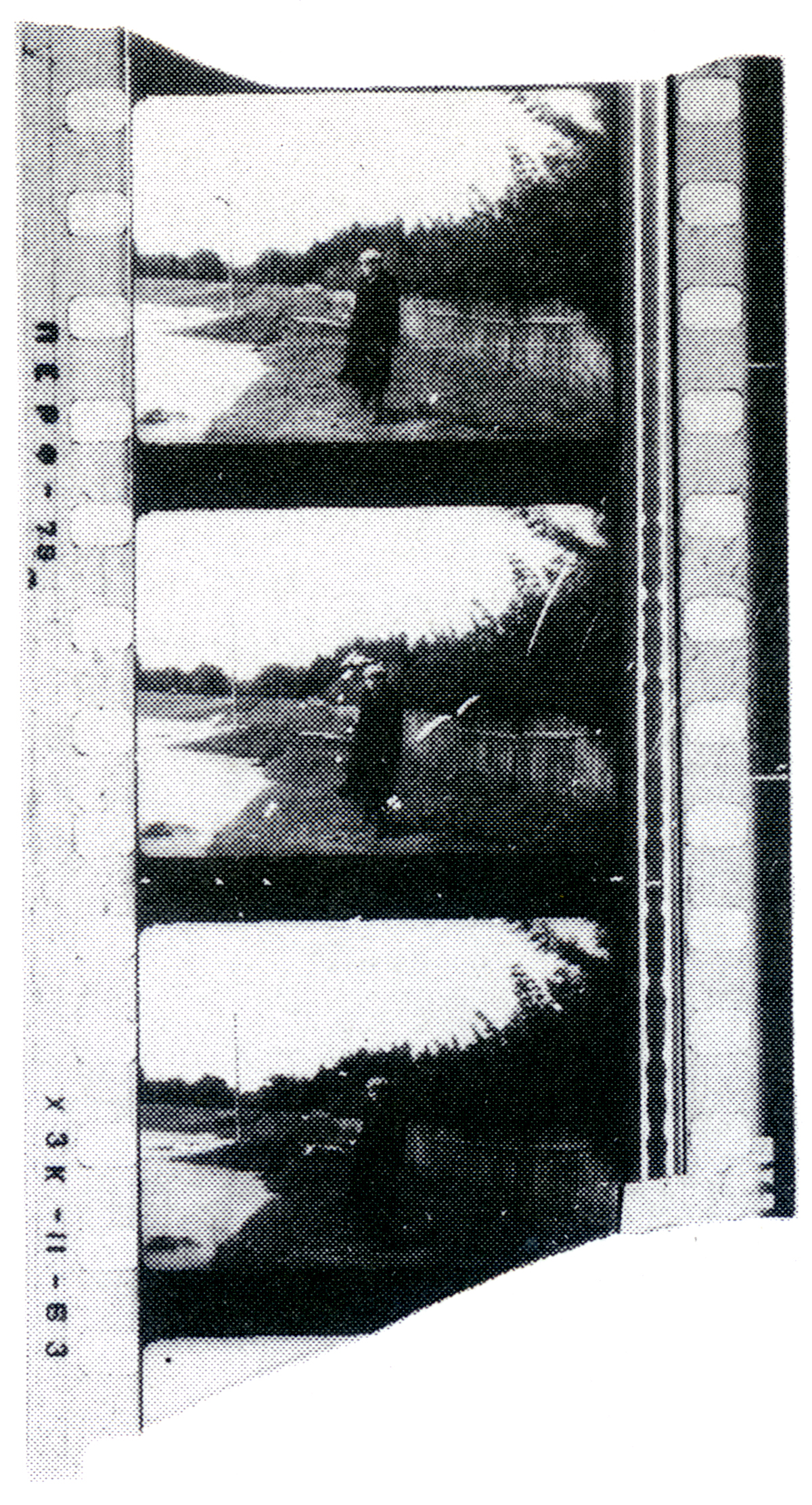

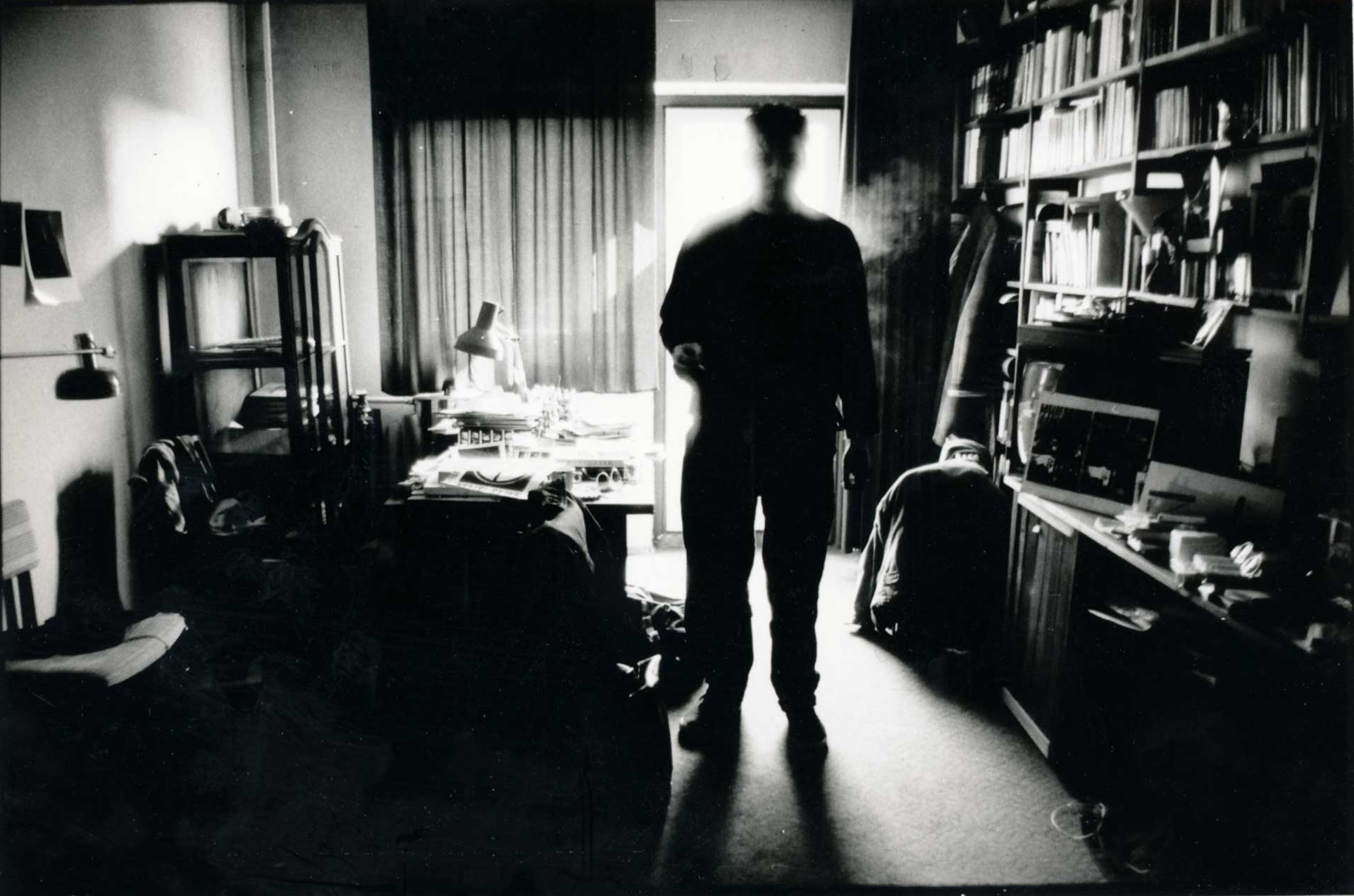

Several years ago, I found a small strip of 35mm film on the sidewalk of Kalajeva Street in Leningrad. Evidently torn from a larger series of pictures, it was at one time, perhaps, a piece of a motion picture. The industrial logo spelled out in Cyrillic by the sprocket holes suggested to me that both the film and the scene it depicted were Soviet in origin, and not the litter of Western tourists. Each of the three frames contained on the film showed the same picture: a man dressed in a long coat and a cap standing between a wooden fence and a body of water. The fence encloses a dense, wooded vegetation, which frames one side of the image. The man stands at the center of the photograph, looking away from the camera toward the water. Between the fence and the water, the plot of ground on which the man stands is grassy and well maintained. Three tall, rough hewn poles form a descending line into the distance of the landscape. Near the most distant pole, a road emerges from the wood and slopes into the water.

Throughout its brief history photography has been presented as a universal language. Photographs of men and women in various conditions of health and sickness, wealth and poverty, community and solitude, have been used to represent the commonality of experience, the relatedness of all to one and of one to all. Yet as I look at this small picture I am aware that whatever shreds of meaning I am able to obtain from it emerge from within myself, from my own history as a “reader” of photographic images, rather than from the meaningful intentions of its author.

This photograph, which was at one moment deemed worthy of preservation, and at another torn from its source and rejected, fascinates me. Abandoned by its author, the image has come into the presence of a reader (myself) who seeks, through recognition of familiar signs (water, fence, telegraph poles, road), to establish a text sufficient to discover its meaning. Absent an authoritative text to tie them together, however, the signs I am capable of distinguishing fail to form a linear narrative; they do not “line up” to tell a story. Without an author to “close” it, the history of the photograph is indeterminate. Its text is open to my interpretation.

Given that we are rarely familiar with the intentions of the authors of images that everywhere surround us, how is it possible that we ever obtain meaning from photographs? More often than not, the photographer will have executed his or her pictures to fit within internationally recognizable aesthetic categories, or genre, such as landscape, documentary, or portraiture. If the photographs that we are viewing function outside such categorization, we may look for meaning by studying the culture from which the photographs have emerged. Finally, viewers may rely on the photographer (or on a critic) to provide a text locating the aesthetic, institutional, or cultural significance of the pictures. In each of these methods for interpretation meaning is determined through narratives that exist outside the immediate relationship of the viewer to the photographic image. Each depends upon an outside authority to construct meaning through a closed or fixed text.

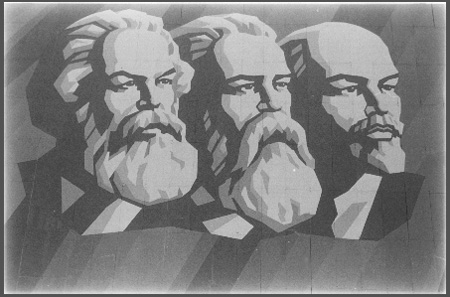

In authoritarian regimes, the state is the ultimate author of all texts. The state exercises its authority through absolute control not only of the artist, but also of the viewer. The state controls not only cultural institutions, such as museums, but also the material that those institutions may present and the media within which such presentations may be discussed. The state controls not only the creation of images, but also their circulation and their destruction. In other words, the authoritarian state controls the words, the images, and the media through which its historical record is created, maintained, and preserved. The state’s absolute control of the image confers upon it a “theological” closure, such that the image is closed to interpretation. This closure is the root of the ideological value of the photographic image in authoritarian states.

Images emerging from totalitarianism may be understood only through the closed or ideological “text” of state control. Appearing to allow the viewer no role in the construction of meaning, the authoritarian text implies a natural and exclusive bond between image and state. The relationship of the photographic image to time (that the event photographed has truly occurred is proven by its presence in the picture) extends, on the two-dimensional surface of the photographic print, to the state. Thus, the state is endowed with the look of history. The relationship of the viewer to the history depicted in the photograph is determined by his or her acceptance of its underlying text of control.

Photographic images emerging from totalitarianism, yet unauthorized by the text of state control, are indeterminate; they are incapable of possessing absolute meaning. Such images possess no fixed text determining their origins or intentions. Unauthorized (or, as they have come to be known, “unofficial”) images engage viewers in the open-ended construction of meaning through the absence of such a text. Unauthorized photographs represent the challenge of meaninglessness to overdetermination. Refuting the state’s absolute control over cultural signification, such images position viewers within a relationship of resistance to the concept of the author, and thus to the authority of the state. Such images need not be “political,” but they are always “active.” In the unauthorized images that come to us from authoritarian cultures, therefore, meaning may be determined as much through the activity that they promote as through the collection of signs that they represent.

The particularly subversive quality of the photographic image, as appealing to the artist working against state control as it is provocative to the state seeking to control it, is its position as both an artwork and a document. The photograph stands, simultaneously, both inside and outside of time. What we experience when we look at a photograph, as John Tagg has noted, is

a double movement which typifies ideological discourse. On the one hand, the ideological construction put on the objects and events concretises a general mythical scheme by incorporating in it the reality of these specific historical moments. At the same time, however, the very conjuncture of the objects and events and the mythical scheme dehistoricises the same objects and events by displacing the ideological connection to the archetypal level of the natural and universal in order to conceal its specifically ideological nature. What the mythic schema gains in concreteness is paid for by a loss of historical specificity on the part of the objects and events.1John Tagg, The Burden of Representation, Essays on Photographs and Histories, Amherst, MA,1988, p.159.

When a photograph is authorized by the state, levels of meaning appear to merge within it, absolutely and seamlessly, to form an ideological text. However, ideology cannot exist independently within the image, but depends upon the viewer to “activate” it. The ideological function of the photographic is contingent upon the viewer’s a priori acceptance of, or faith in, the image’s cultural signification, as determined “theologically” by the state. The absolution of the authoritarian state is validated by the viewer’s unquestioning faith.

The medium of photography has proved a fertile ground for artists whose work resists the authority of the text. Those who produce photographic images within authoritarian states often use the medium to disrupt ideological discourse. In so doing, they disrupt the apparent relationship of the state to time and to history. They profane the natural order, showing, to paraphrase Roland Barthes, that a text is not a line of signs releasing a single “theological” (or, as Tagg would have it, “universal”) meaning, but “a tissue of quotations drawn from innumerable centres of culture,” none of them original, none of them absolute. It is for this reason that artists working within authoritarian regimes are often prohibited from producing photographs that do not bear the authorization of the state.2Roland Barthes, Image – Music – Text, New York, NY, 1977, p.146.

2.

By [the end of the 1970s] only a few artists remained to be categorized as “prohibited,” only those “impenitent recalcitrans” [sic] like… Tibor Hajas… who, at times deliberately challenging authority, refused to acknowledge any taboos clad in the costumes of politics or morality… It was only the “recalcitrans” who stuck out from the peaceful general view.3Péter Kovács, Hungarian Art in the 20th Century. The End of the Avant-Garde, (1975-1980), Székesfehérvár, Hungary: István Király Múzeum,1989, p. 6.

In the catalogue accompanying a survey of Hungarian art from 1975 — 1980, Péter Kovács, Director of the István Király Múzeum in Székesfehérvár has noted that “the ‘avant-garde’ [of that era] had a rest and seemed to peacefully settle down: it turned main stream.”4Kovács, p. 6. To “turn main stream,” however, implies not only that the avant-garde had, by the mid 1970s, accepted the Hungarian state, but also that the state had accepted the avant-garde. It is significant that this statement, summing up a period in the artistic history of a nation as one of general contentment, comes to us from one of that nation’s important cultural institutions. Other texts from the same period tell the story from a somewhat different perspective.

It was during the late 1970s that Tibor Hajas created his most mature and important works, a series of actions performed for photography. Formally, Hajas’ actions followed the lead of the Viennese Actionism. Working in Austria since the early 1960s, the work of this group of artists, led (arguably) by Hermann Nitsch, merged theatre with artistic production, replacing language with sensation by “pouring out, spraying, splashing, smashing, tearing up, tearing apart meat, or smearing or soiling something,” activities accompanied by the noise of a “screaming chorus” of woodwinds and percussion instruments. The object of the action was to liberate “accumulated and blocked up psychic energies.”5Hermann Nitsch, Hermann Nitsch,1960 – 1987, Naples, Italy,1987, p. 32. Liberation, therefore, rather than any finished piece, was the object of (especially Hermann Nitsch’s) Actionism.

The resemblance of Hajas’ work to the Viennese Actionists’ does not extend far beyond appearances. In contrast to the psychic liberation advocated by the Vienna group, Hajas’ performances challenged audiences against the danger of moral and intellectual passivity. While the role of the spectator in the Viennese Actionism is basically compliance, Hajas’ audiences are prompted to direct participation.6“The spectators are required, during the performance to [be] concentrated and let abandonment, reflection and pleasure, meditation and excess take over.” M. D’Ambrosio, in Hermann Kitsch, 1960 -1987, p.112. In Dark Flash, a performance held at the Galeria Remont in Warsaw, 1978, Hajas hung from the ceiling by a rope bound to his wrists. In his hands he held a camera. As the blood drained from his hands and cut off his circulation, Hajas photographed his audience until, at last, he passed out. Had his audience not finally cut him down, the artist might have died. His film documents their indecision.

Hajas’ performances are reminiscent of the early work of American artist Chris Burden. The provocative intentions of Dark Flash are remarkably similar to those of Burden’s Back to You, 1974, in which a member of the audience was invited to stick push pins into the artist’s body; of Velvet Water, 1974, during which an audience of art school students watched via video monitor as Burden collapsed after submerging his face in a sink and attempting to breathe water; and of Kunst Kick, 1974, when, during the public opening of the Basel Art Fair, Burden had himself kicked down a flight of stairs, two or three steps at a time. The struggle of the audience is not with the pain that the artist inflicts upon himself, but with its complicity in inflicting that pain through failure to prevent it. The struggle of the viewer is that of reader against author, of actor against text. The viewer must go against the grain of the text and put an end to it, or s/he must accept the role of passive compliant. The viewer becomes, simultaneously, both subject and author of the artist’s work.

Júlia Szabó has noted that Hajas experienced the element of “hidden risk” in his performances: had the audience not come to his rescue, he might have died. This concept of hidden risk returns us, once again, to the notion of the open, or unauthorized, text. Hajas’ risk extends from his own body to the body of viewers, his audience; the degree of pain that he inflicts upon himself is directly proportionate to his viewers’ acceptance of their authority to end it. As Hajas wrote, “we do not, on our own, deliberately have to do anything to incur damnation; our participation is a prodigal luxury.”7Tibor Hajas, Hajas Tibor, 1946 – 1980, Magyar Mühely, np. Two retrospective publications, both titled Hajas Tibor, 1946 – 1980, will be cited extensively. To avoid confusion, the earlier publication, edited by Lázsló Beke, will be referred to as Hajas Tibor, 1946 – 1980, Magyar Mühely. The exhibition catalogue published by the István Király Múzeum in 1987 will be referred to, simply, as Hajas Tibor, 1946 – 1980.

By transforming the role of viewer to participant, and finally to author, Hajas conferred upon viewers the authority to challenge his text. He empowered his audience to take positive action against suffering, to refuse passive complicity. The closed room of the performance space extends to implicate the closed text of the artist, as well as the closed state of authoritarian culture. By acting against the artist’s text, the audience also acts against the text of state culture, “opening” it to interpretation. Within the authoritarian state in which Hajas worked, this was regarded as an act that neither he nor his audience was authorized to commit.

“Censorship,” as writer Miklós Haraszti has noted, “is the final glaze that the state applies to the work of art before approving its release to the public.”8Miklós Haraszti, The Velvet Prison. Artists Under State Socialism, New York, NY, 1987, p. 9. Tibor Hajas was “rehabilitated” in 1986, six years after his death, when a small selection of his works exhibited at the Liget Galéria in Budapest failed to arouse official indignation. Following the lead of the Liget, the István Király Múzeum in Székesfehérvár opened a retrospective “memorial exhibition” for Hajas in early 1987. The exhibition Hungarian Art of the Twentieth Century, The End of the Avant-Garde, presented at the István Király Múzeum in 1989, nine years after Hajas’ death, was among the first to present his work within the larger context of the Hungarian avant-garde. In his text for the catalogue of that exhibition, curator Péter Kovács wrote that “even with the really provoking works of… Tibor Hajas challenging accepted values it was rather the thorny behavior than the works’ real or presumed political message that deterred the authority.”9Kovács, p. 7. Implicit in this statement is the suggestion that although the power of Hajas’ work to provoke is rooted in his audiences’ common acceptance of the values that he challenged, it was his behavior in provoking, rather than the effect of his provocation, that resulted in his prohibition.

Citing Hajas’ attitude rather than his effect, Kovács’ statement reiterates former Politburo member György Aczél’s declaration, made in 1982, that “there is no opposition that has to be reckoned with in Hungary,” only a few maladjusted, untalented, mentally troubled and disappointed people who blame society for their failures.10Cited in Peter Toma, Socialist Authority: The Hungarian Experience, New York, NY: Praeger, 1988, p. 37. Kovács relegates Hajas to the status of enfant terrible. Hajas’ importance to Hungarian culture of the 1970s, and to the generation of artists working in Hungary today, is sorely diminished by this interpretation. Hajas was more than a “recalcitrant” or “political artist,” butting his head stubbornly against the state. The importance of his work lies not in its power to undermine the values of his audiences, but in its capacity to reinvest those values with meaning. Hajas, like his contemporaries Miklós Erdély and Gábor Bódy, sought to empower his audiences with the authority of moral responsibility. He took his audiences on a journey, similar to that depicted in Miklós Erdély’s photographic series Time Journey I — V, 1976, in which viewers were brought face to face with the consequences of their actions.

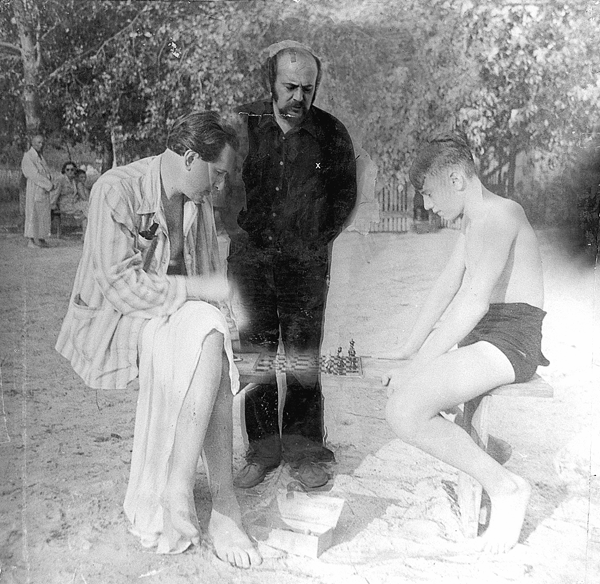

Using exposures lifted from old family photographs to construct a single self portrait, the third photograph in Erdély’s series, subtitled 1934, depicts the artist at three different stages of his life. Erdély as a boy plays a game of chess with Erdély as a young man, while Erdély as an older man, the artist, observes their game. Erdély the artist knows the nature of the game that the younger men are playing, and he knows which of the two will win.

Time Journey I —V is a complex series of “observations,” of which 1934 stands as the centerpiece. The viewer of the series stands in time with Erdély the artist. In common with the artist, the viewer is a time traveler; s/he observes the artist observing himself. Simultaneously, the viewer is implicitly aware that s/he is observed by the artist. The artist, who created the series for the viewer’s observation, stands between past and future, looking in both directions. Thus, the viewer may observe with the artist, but not without being observed by the artist. This inescapable relationship of observer to observed in which the viewer has been trapped extends telescopically from time past to time future. To know the past is to see the future. Yet to see the future is to deny chance, to cancel the unpredictable. A life denied of chance, a completely predictable life, is but a slave to the certainty of time. A life denied of chance is no longer free.

It is not for freedom itself, total freedom, but for faith in freedom, that Erdély the artist observes Erdély the boy and Erdély the young man playing. This distinction is critical, for it is precisely against freedom through faith (freedom through art, freedom through work, freedom through socialism) that the work of Erdély and Hajas speaks. Such freedom, contingent upon ideology, is false and fleeting. It is as a result of such faith, believing creative expression to be the ultimate act of liberty, that we come to observe the work of these artists. Yet in observing, we are drawn into their trap. The artist locks the door behind us. The artist engages us, demanding that we see that our histories (our family albums) are easily falsified, our beliefs easily corrupted. Our past (the text of history) is our bondage, our truth is our lie. The artist demands that we reject bondage, that we abandon the safety of faith, grounded in ideology, and experience total freedom.11See Hajas’ Recompense, Hajas Tibor, 1946 – 1980.

Like Erdély, Hajas placed the concept of total freedom within the grasp of his audiences. That he did so in Hungary in the 1970s insured that he would, more than once, come into conflict with the state. Yet Hajas was not a political artist. Rather, he was an activist (as the term was used to define a tendency in German expressionism) who “reformed [anarchistic impulses] in the direction of neo-enlightenment by elevating psychological revolt to the level of practical and social reform.”12Renato Poggioli, The Theory of the Avant-Garde, Cambridge, 1968, p. 27. Hajas placed ideas above art, and treasured freedom above all.

Touching live wires can cost… lives. This was something Tibor Hajas knew and wanted and the forbidden touch brought him its double reward: annihilation and total freedom. Total freedom, perhaps the most monumental slogan that the avant-garde could conjure up before the eyes of mankind but which it was, of course, unable to materialize in socially feasible terms. Tibor Hajas’ influence was thus also condemned to remain limited but one thing is certain: everyone who met him or was confronted with his works could not but feel this touch of total freedom.13László Beke, in Hajas Tibor, 1946 – 1980, Magyar Műhely, np.

3.

I cannot conform to you, I cannot be at your mercy. I have become the guidepost whether you wanted it or not; you can only refer to me, you can only return to me. But it is not necessarily compulsory; we are independent of each other. Don’t let yourself be deceived, my lord. My lord, don’t let yourself be deceived.14Tibor Hajas, in Vigil (1980), Hajas Tibor, 1946 – 1980.

In the decade since Hajas’ death Hungarian culture has risen from what appears to Western eyes as a deep slumber. Yet if this was slumber, then the nation’s culture must have been shaken to consciousness by nightmares. Indeed, during the years of Soviet occupation a powerful undercurrent of Hungarian culture has been active in the works of Béla Kondor, Miklós Erdély, Gábor Bódy, Tibor Hajas, and numerous others. Largely unrecognized in the West, these artists have worked, often under duress, to maintain the vitality of Hungarian tradition. Their activities are testament to the will of the Hungarian people, exemplified by the post-World War II election defeats of the Soviet dominated Communist Party, by the revolution of 1956, and by the recent defeat of the Party in the elections of 1990, for self determination.

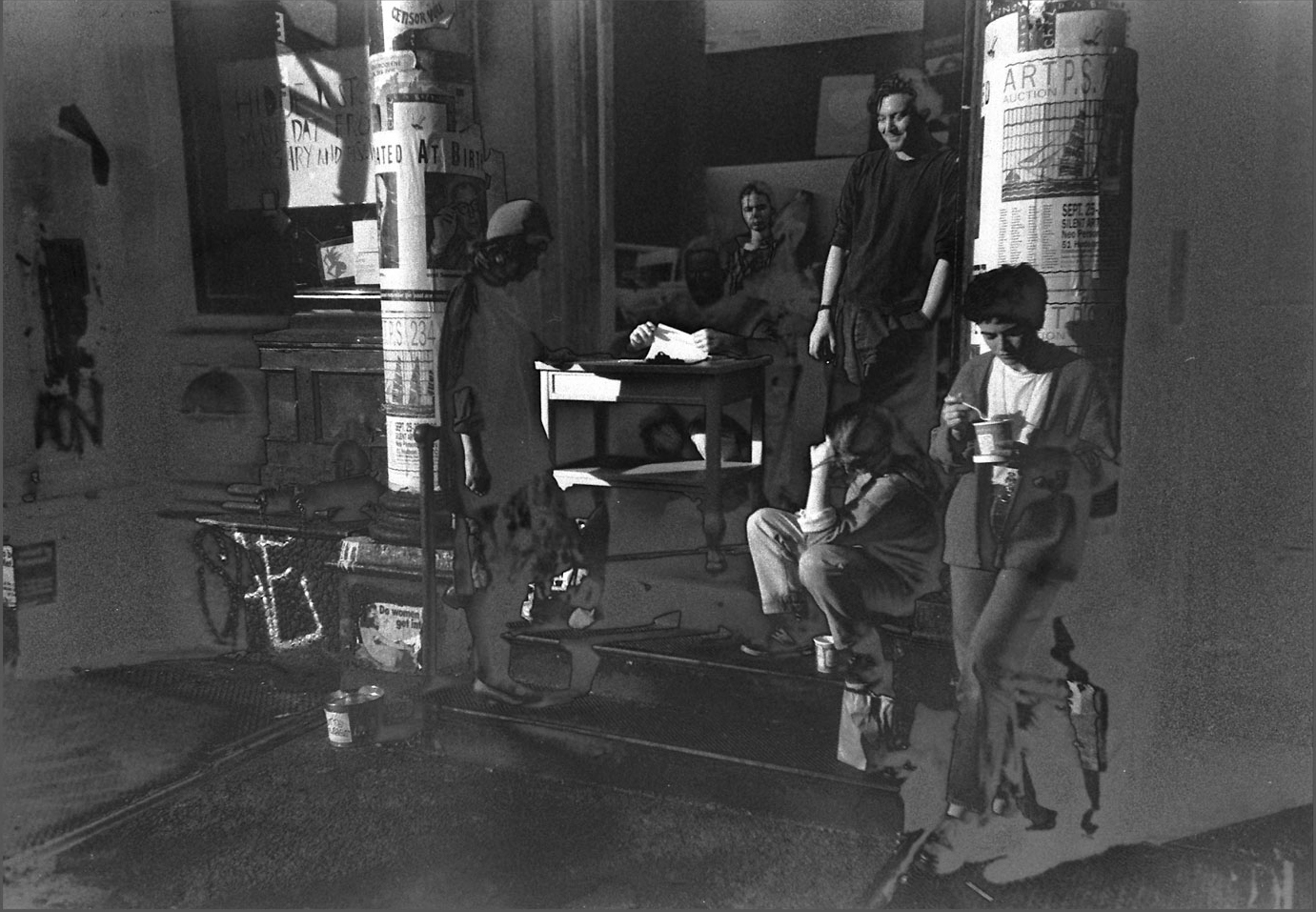

Hajas was not alone in his relentless investigation of moral and aesthetic values. Nor was he the only artist to realize his own body as the site of conflict. During the early 1970s, the Squat Theatre, then known as Studio Kassák, began to merge the art of performance with the reality of the audience as a direct result of prohibition. “The place is an apartment on the fifth floor, where we played whatever we wanted to, but the danger played with us… The personal fate, culture and gestures of the spectators became part of the theatre, just like ours. The result: a very selective and subtle communication system, a sort of symbolism based on the realities of this ‘apartment theatre.’”15Stephan Balint, New Observations, #40, New York, NY, 1986, p. 2. Following the group’s departure from Hungary in 1976, they continued to bring “real life” together with theatre, by performing in a large New York City storefront. “The storefront was a situation where fiction and reality could mix because there was a fiction on stage and there was a real life behind as background, and sometimes the real life intervened.”16Balint, p. 7.

“Reality” was also the material of the “experimental” Group Inconnu. “Experimentation, which aims at pointing out to the viewers, more precisely, to the whole of society, the limits of the autonomy of the individual. This is why the field of reality is more appropriate for artistic and social activity, since here the falsity of illusions and substitute gratifications is immediately revealed and the ‘condition humaine’ manifests itself in its own nature.”17Gabriella Ujlaki, 2. Mini Retrospekt, Group Inconnu, Budapest,1985, np. Throughout the 1970s Group Inconnu merged aesthetic form with political expression using body art, performance, installation, and mail art. The activities of Group Inconnu were consistently prohibited through the 1980s. Toward the end of the decade, the group curtailed its artistic activities to aid the growing number of independent political organizations in Hungary, providing access to printing, telefax, and other services still under state control.

The work of Tibor Hajas is distinguished from that of his contemporaries precisely by its falling between aesthetic and political spheres, into the realm of the personal. Hajas sought to “dispense with my clothes, pastimes, walls, objects and dates that surround me now. To grow as thin as to become mere voice; to lose everything that binds me here now.”18Tibor Hajas, in Vigil (1980), Hajas Tibor, 1946 -1980. Falling into the category defined by Renato Poggioli, in his Theory of the Avant-Garde, as “agonism,” Hajas offered himself as a guidepost for future generations. “In short, agonism means sacrifice and consecration: an hyperbolic passion, a bow bent toward the impossible, a paradoxical and positive form of spiritual defeatism.”19Poggioli, p. 66. (emphasis added) This consecration, Poggioli continues, constitutes “[an] immolation of the self to the art of the future [which] must be understood… as the fatal obligation of the individual artist.”20Poggioli, p. 67. Thus, it is in the work of Hungary’s contemporary artists that we may best observe Hajas’ influence. In the works of Tamás Szentjóby, Ákos Birkás, Bálint Flesch, Antal Jokesz, and others too numerous to mention, Hajas’ contribution to Hungarian culture is directly revealed. Of particular note are János Vető, Zsuzsanna Ujj, and Tibor Várnagy.21For information on contemporary photography in Hungary, see The Metamorphic Medium, New Photography from Hungary, Oberlin, Ohio: Allen Memorial Art Museum, 1989.

It is impossible to speak of the work of Tibor Hajas without also speaking of János Vető, his collaborator. It was Vető who worked with Hajas, photographing his private performances for camera, and it is Vető’s sense of space and sequence that imbued these images with an aesthetic drama that parallels the moral and physical drama of Hajas’ actions. In the 1980s, Vető worked extensively as a musician, most notably with the underground “cassette band” Trabant. In his recent photographic work, Vető defies textual interpretation using a layering strategy, apparently merging objects from different images and then partially obliterating them by scratching them out of the negative or by overpainting them in the print. One recent installation of Vető’s work, constructed in 1989 at the Contemporary Art Forum of Almássy Square, presented photographs attached to hinged, book-like binders mounted onto a pile of wooden tables and chairs. The tables and chairs were taken from local schools and culture houses where, not long ago, such work would have met with disapproval. From within this disorderly mound of hard, authoritarian furniture, Vető’s photographs appear to emerge as the new textbooks of Hungarian culture.

Zsuzsanna Ujj is today one of the few Hungarian artists whose work explores simultaneously the mediums of performance and photography. A poet, performer and musician, Ujj’s exhibitions are often accompanied by actions and concerts. In her images, prepared privately for the camera, Ujj is always her own subject. In an untitled series prepared in 1986, Ujj focuses upon the cultural construction of sexuality using a series of poses, alternating between violence and vulnerability, to confront the viewer. Returning the gaze of the viewer, Ujj defies the borders of the print. The anonymous space of the action extends through the print to the space of the gallery and to the viewer within that space. Her photographs transform the tradition of the passive female nude into a site of physical conflict in which the viewer is directly implicated.

Ujj’s most recent photographs, a series of sculptural torsos, return to the subject of the female nude. Addressing it from both an aesthetic and a critical perspective, Ujj’s torsos are as formally elegant as they are conceptually disquieting. Using high contrast black and white film to achieve her effect, Ujj’s body, dismembered and devoid of personal detail, emerges dramatically from the black background. The viewer is instantly and pleasantly reminded of countless similar torsos s/he has seen in museums and public places in which the nude female body has been canonized. Yet it is precisely within this pleasant moment of recognition that Ujj’s critique begins. As Kate Linker has written, “identity is constructed only through images acquired from elsewhere.”22Kate Linker, in Art After Modernism, Rethinking Representation, New York, NY, 1984, p. 396. Identifying the torso, we identify our historical relationship to it, ultimately identifying ourselves by it. Our pleasurable response to Ujj’s torsos implicates us as complicitous partners in the patriarchal construction of female sexuality through visual representation.

The photographs of Tibor Várnagy, though formally distant from those of Tibor Hajas, continue the dialogue with textual authority so prominent in the work of the latter. Várnagy’s series of TV Contacts, Fire Prints, and Black Squares represent an extraordinary investigation of the photographic image as a message carrier. Of his work the artist has written,

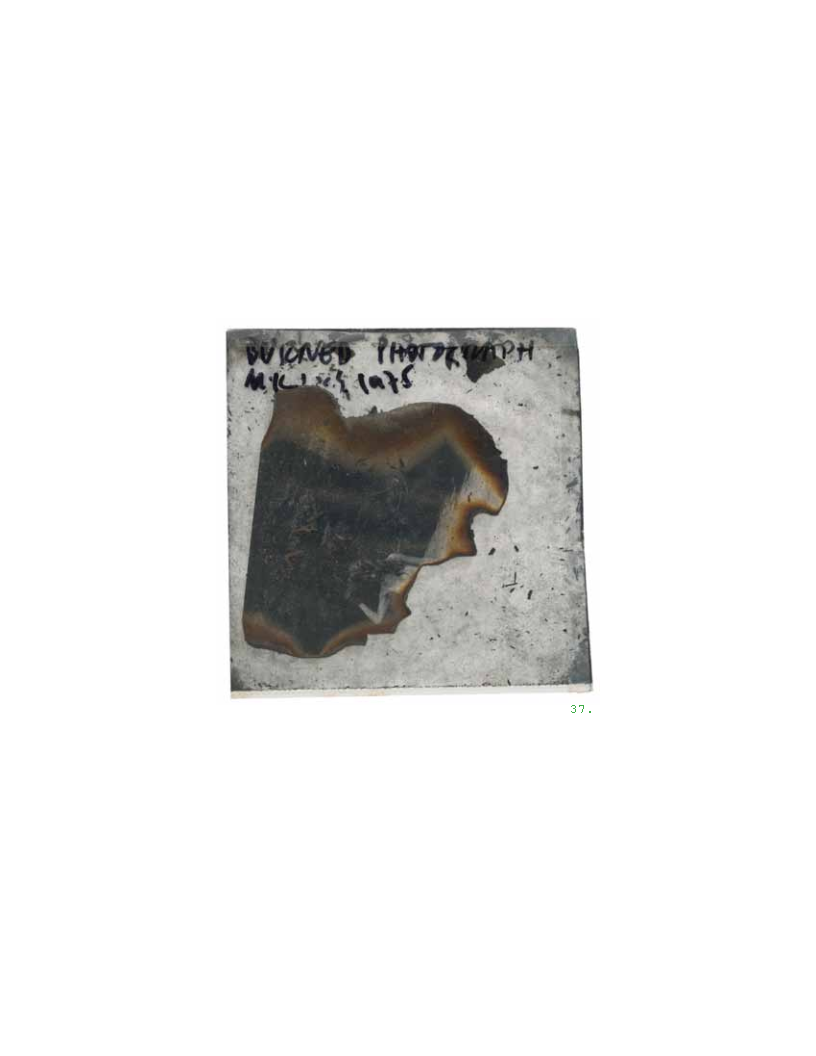

In 1985 I made my first series of [cameraless] photographs by placing photographic paper on the television screen during broadcasts. Prints made this way lost the photographic sharpness that makes them appear specific or concrete. It seemed that behind the surface of the photographs, where the documentary value is carried, common symbols exist. Later I turned to burning the unexposed photographic paper, developing the remaining surface that had been exposed by its own flame. The resulting images were surprisingly rich formally, in places graphic, and rich in tonal variations. In both series the gesture became significant. I made the black squares in 1988 by illuminating the photographic paper through the empty negative holder. All these may be taken as paraphrases of Malevich, in which the variations are caused by the possibilities of another medium. In contrast to his pieces, I made rectangles because the standard commercially available photographic paper comes in the shape of rectangle: I used these vertically. I found it necessary to overexpose these rectangles, a process that destroyed their geometric movement, introducing the possibility of a new dimension. The ambivalence resulting from this process is positive, or the interpretation of a negative statement; and finally, but not least importantly, the process addresses the issue of multiplicability or the problem of quantity.23Tibor Várnagy, in The Metamorphic Medium, New Photography from Hungary, p. 40.

Várnagy’s photographs seek to divest objects of meaning by denying the validity of their cultural functions. This divestiture extends to implicate the belief that meaning exists independently within the photograph itself. In his TV Contacts, Várnagy plays simultaneously with the authority of the artist, using his own initials in the title of the series, and with the authority of the state controlled television media from which the images were lifted. The origin of the authoritarian text has been blurred both in the refusal of the artist to function as a “creator” (the eye behind the camera) of messages, and in the transformation of the televised images from rigidly political message carriers to purely formal objects. Like Hajas, Várnagy reveals by his own action that the authority of the text (of the state in his TV Contacts, of art history in his Black Squares, and of the photographic genre and materials in his Fire Prints) can not exist independently, but depends upon the viewer for its validation and repetition. The artist is also viewer. Both subject and object, s/he is at the center of the production of meaning in every text. Only through the artist/viewer’s active participation in the construction of meaning is the ideological function of the text subverted, and only through such subversion is the concept of total freedom within reach.

4.

You could never defend yourselves before, you could never offer assistance, but now this condition bears my name. I am perfectly aware, more so than yourselves, what you stand to lose while you are here. The longer, the more. And a single moment suffices for a catastrophe. I am deliberately taking my time; deliberately holding you up. Holding you up to give catastrophe a better chance. I would like catastrophe to strike you while you are wasting your time here. It would make these moments valuable, significant, set apart, unique. It would give them weight. I could give you the experience of the irremediable. At last you could realize what you are missing.24Tibor Hajas, in Recompense, Hajas Tibor,1946 – 1980.

In the final years of the 1980s, Hungary has been dramatically transformed, politically and culturally. The removal from office of János Kádár, mouthpiece for the Soviet power that crushed the Hungarian Revolution for more than thirty years, has been swiftly followed by the removal of those who sought to replace him. As the borders between Hungary, Austria, and Czechoslovakia have opened, the dictatorship of the Czechoslovak Communist Party has also crumbled, rekindling in the people of the Danubian nations the hope for international unity. Simultaneously, fience nationalist disputes between Central European nations, closed to discussion during the period of Soviet occupation, have been reopened. As Central Europe emerges from domination, the nations of which it is composed have reawakened to the settling of old accounts. The threat of violence, as recent attacks upon the Hungarian minority in Rumania have shown, is all too real.

Although they may not have been aware of it, the work of Hajas and his contemporaries is symptomatic of the earliest movement toward reformation in the nations of the Warsaw Pact. The period in which Hajas worked (the 1970s) is traditionally viewed as the close of the period of thaw following the Khrushchev years. This view of “open” and “closed” periods of artistic expression fails to acknowledge the fact that even in periods of repression artists in Hungary have continued to develop their work independently of the state. The development of independent ideas during the Khrushchev era did not simply end upon his replacement by Brezhnev, but continued by exercising a profound influence upon younger artists, who pursued their ideas and convictions into the 1970s and 1980s. The work of Hajas and his contemporaries occurred during a time of great flux and uncertainty in Soviet Europe. Therefore, the independent culture of artists working in this period may be better understood as pivotal, the point upon which both the end of the old era and the beginning of the new tenuously rocked. Artists who worked during the old era continue, in some instances, to influence. The efforts of those who, like Hajas, helped to create the new era, remain unsurpassed.

Finally, it is critical to recognize that the authority opposed by Hajas and his contemporaries is not one that can be named. As the authority of the socialist state has passed, encroaching capitalism threatens to take its place of power. As revealed in the TV Contacts of Tibor Várnagy, however, the authority of the state exists on a parallel with the authority of the artist; both seek to direct the faith of the viewer. It is authority in all its many forms, therefore, that these artists resist. Recognizing the contradiction in his very words, in 1980 László Beke declared that “to recall the life and works of Tibor Hajas is to commit trespass: disturb something which is definitely at rest, mutilate what is whole, classify that which is unclassifiable, degrade what has for eternity become more than that.”25László Beke, Hajas Tibor, 1946 – 1980, Magyar Műhely, np. Yet as Hajas has so clearly shown, there is no forbidden ground. There exists no absolute whole that is not also eminently dividable. Hajas left no body to rest, not even his own.

I am grateful to Steven High, László Beke, Andi and Tibor Várnagy, István Halas and Zsuzsanna Ujj, and Deborah Chapman for their generosity and assistance during the preparation of this essay. Typos in the original were corrected in this edit (2002).

Recalling Hajas, in Nightmare Works: Tibor Hajas, Steven High ed., Anderson Art Gallery, Richmond, VA., 1990

Liget Gallery page:

http://www.ligetgaleria.c3.hu/CafeHajas.htm

John P. Jacob is an artist and independent curator who works extensively with artists in Eastern Europe.

The Missing Picture: Alternative Contemporary Photography from the Soviet Union

Jacob travelled to the Soviet Union the first time in 1986. He traveled with a tourist visa and visited Moscow and Leningrad. Jacob and Katy Kline, director of the List Visual Arts Center (LVAC) at MIT, agreed that, depending on what opportunities he encountered there, he might guest-curate a subsequent exhibition, following Out of Eastern Europe. Jacob initially planned to organize a survey exhibition, mirroring his work on Out of Eastern Europe. That plan was ultimately scrapped, in part due to the vast geographic expanse of the USSR and the difficulty of travel for a foreigner. More significantly, the exhibition sought to respond to the sweeping and unexpected changes taking place in the USSR at the very moment Jacob was working there.

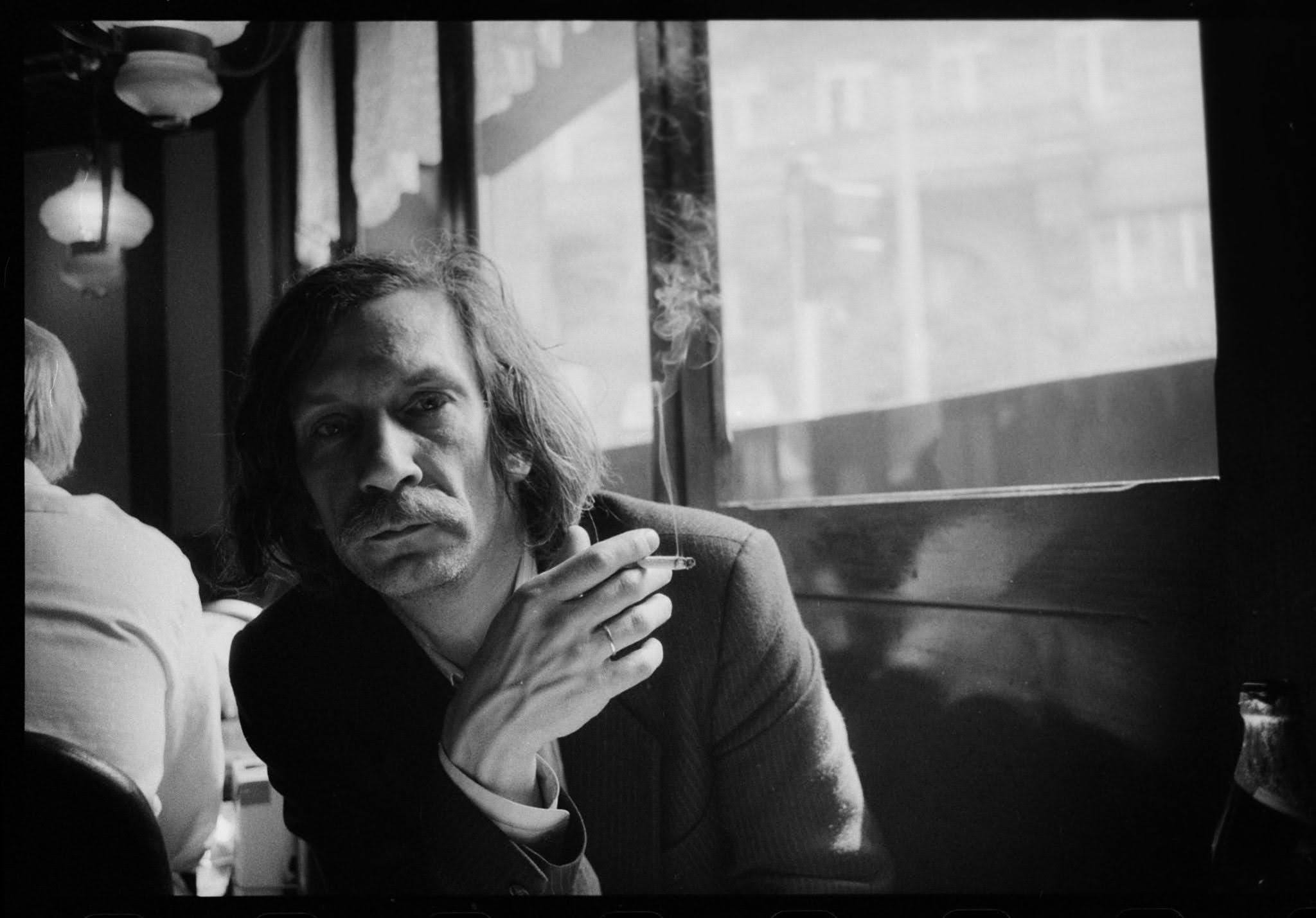

For his first visit, Jacob travelled with a contact list given by Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin. His primary contact in Moscow was Igor Makarevich, a conceptual artist and member of the Collective Actions group who was active in Moscow’s underground art scene since the 1970s. Makarevich was a contributor to Second Portfolio exhibition in Budapest (along with the Gerlovins and Vagrich Bakhchanyan, based in the US). He introduced Jacob to other members of the Collective Actions group, and also to Alexey Shulgin, with whom Jacob subsequently worked as closely in the USSR as he did with Sachse and Várnagy in Eastern Europe. The Ukrainian photographer Boris Michailov also had a strong connection to Moscow Conceptualism, was a member of the Immediate Photography Group with Shulgin, and was introduced to Jacob at this time.

American tourists in the USSR were few in the mid-1980s, and it was illegal for Soviet citizens to interact with foreigners. All communications were subject to monitoring. Jacob’s meetings during that first visit were clandestine, held in private apartments or open public spaces, and sometimes hushed to prevent neighbors or strangers from hearing English spoken. Those he met with all agreed that the legal technicalities and political realities that made an exhibition of Eastern European photography possible in the US, as Jacob’s personal collection, were absent in the USSR. It was dangerous. Nevertheless, Soviet artists, especially those of Makarevich’s generation, had developed strategies for working and communicating about their work. They encouraged Jacob to return, and, when he did, they used what resources they had to support his project.

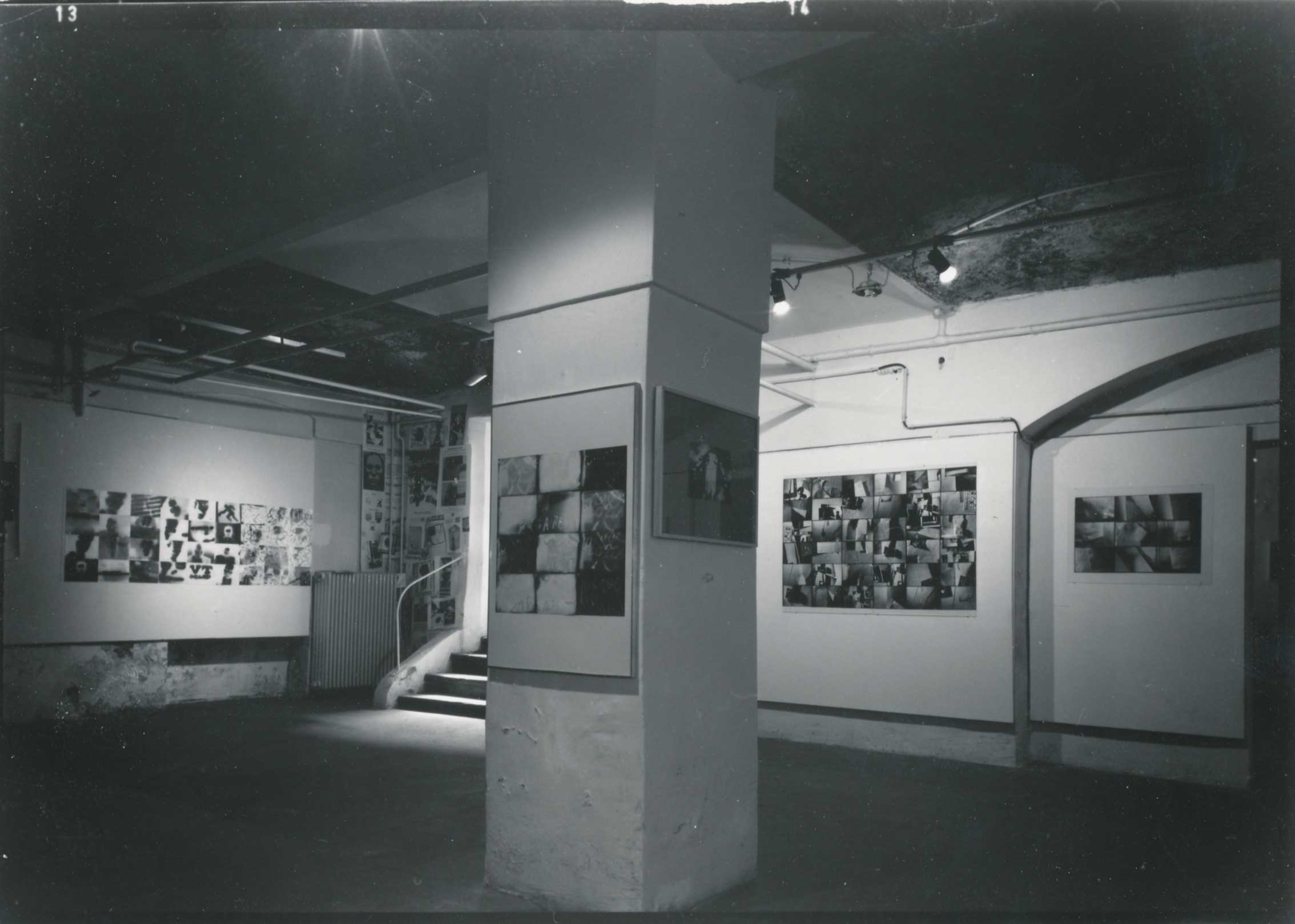

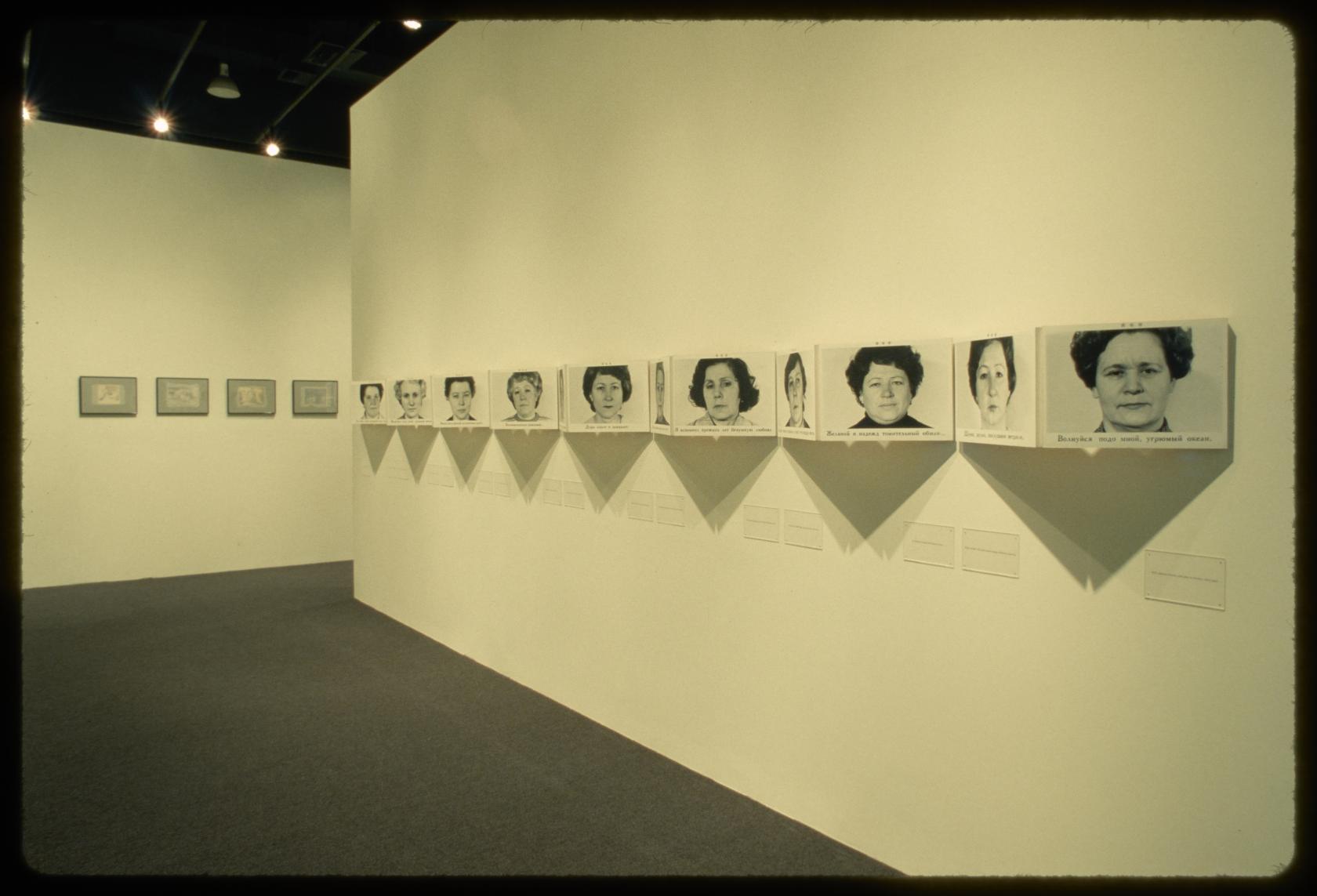

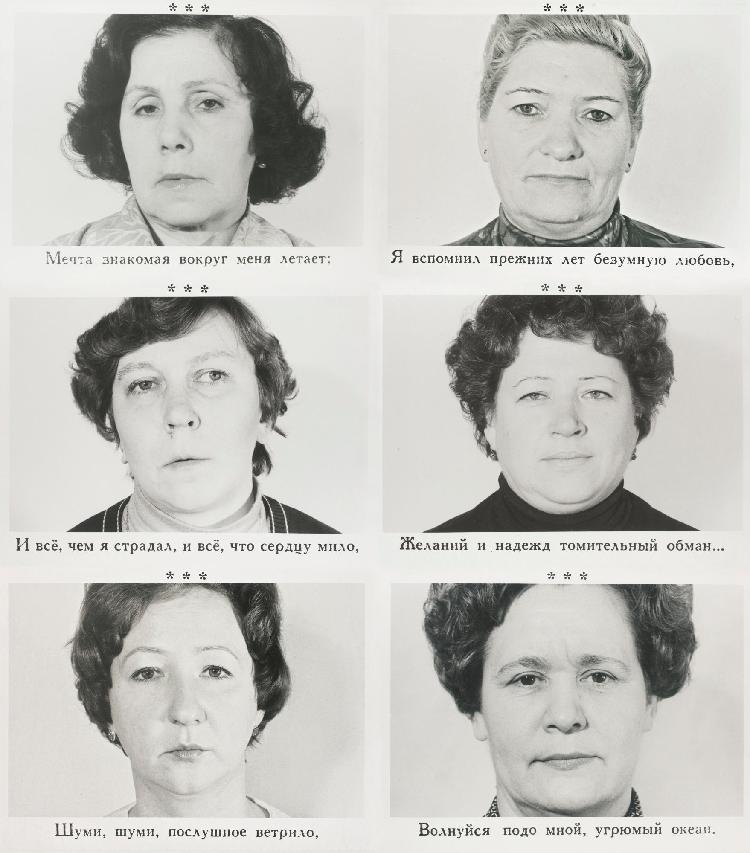

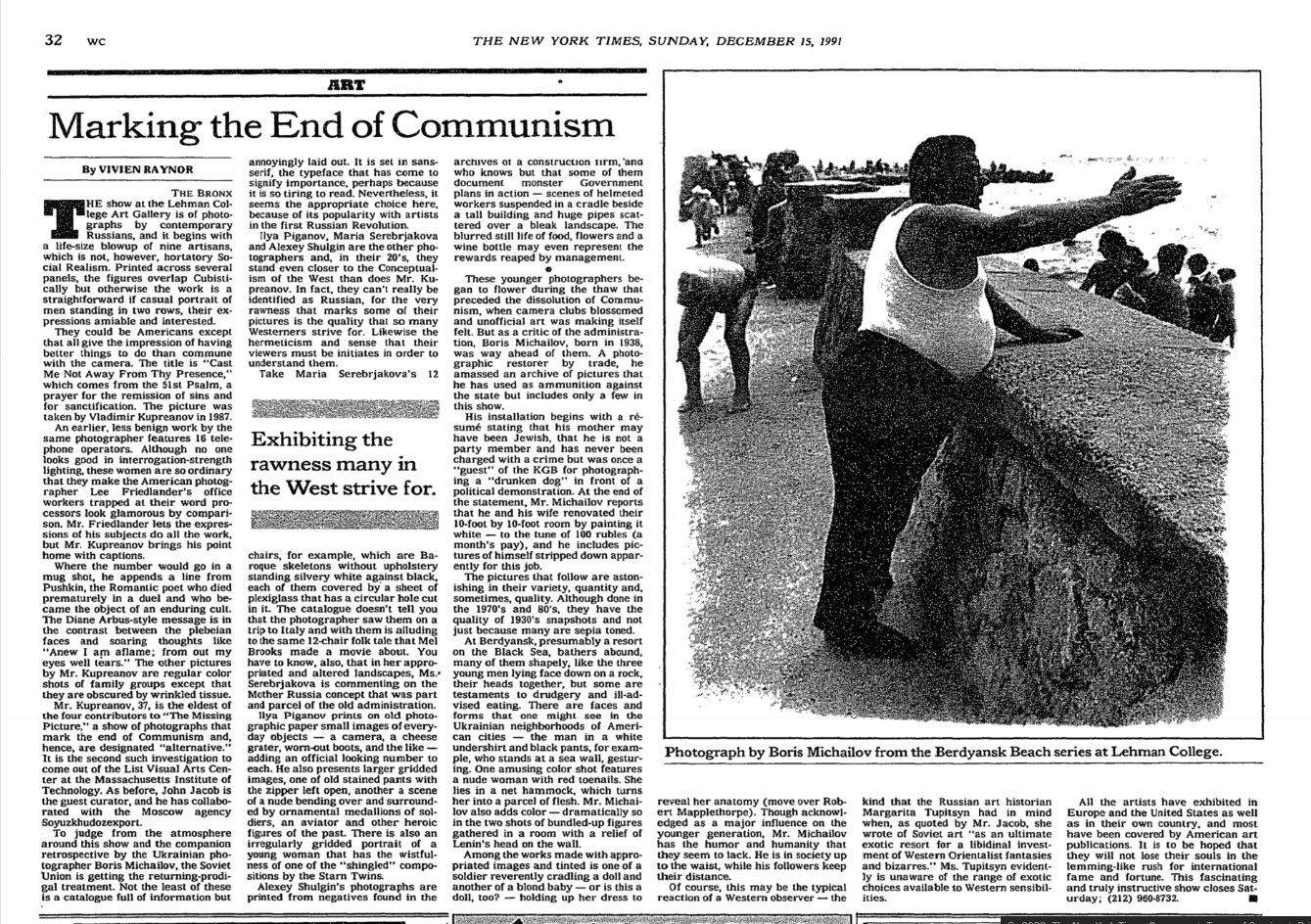

Jacob returned to the USSR three times, in 1988, 1989, and 1990. During each subsequent visit he witnessed changes that, in 1986, would have been unthinkable. Jacob resolved that the exhibition should be about the reciprocal impact of those changes on photography; a historical moment both shaping photography and being shaped by photographs. Unlike others responding to change in the USSR from within institutions or from abroad, Jacob was already on the ground. He was known to the photographers, and trusted as a peer. It was this unique confluence, and the fact that the history of Soviet photography was known to the West, that allowed Jacob to convince both the photographers and the LVAC to do something wholly unexpected. When it opened at MIT in 1990, The Missing Picture presented a one-person exhibition of photographs by Michailov, then little known outside the USSR. It was the introduction of Michailov’s work in the US as a mid-career retrospective, and would be transformative for him. The Missing Picture also presented a group exhibition of four young Soviet photographers inspired by Michailov: Vladimir Kupreanov, Ilya Piganov, Maria Serebrjakova, and Shulgin.

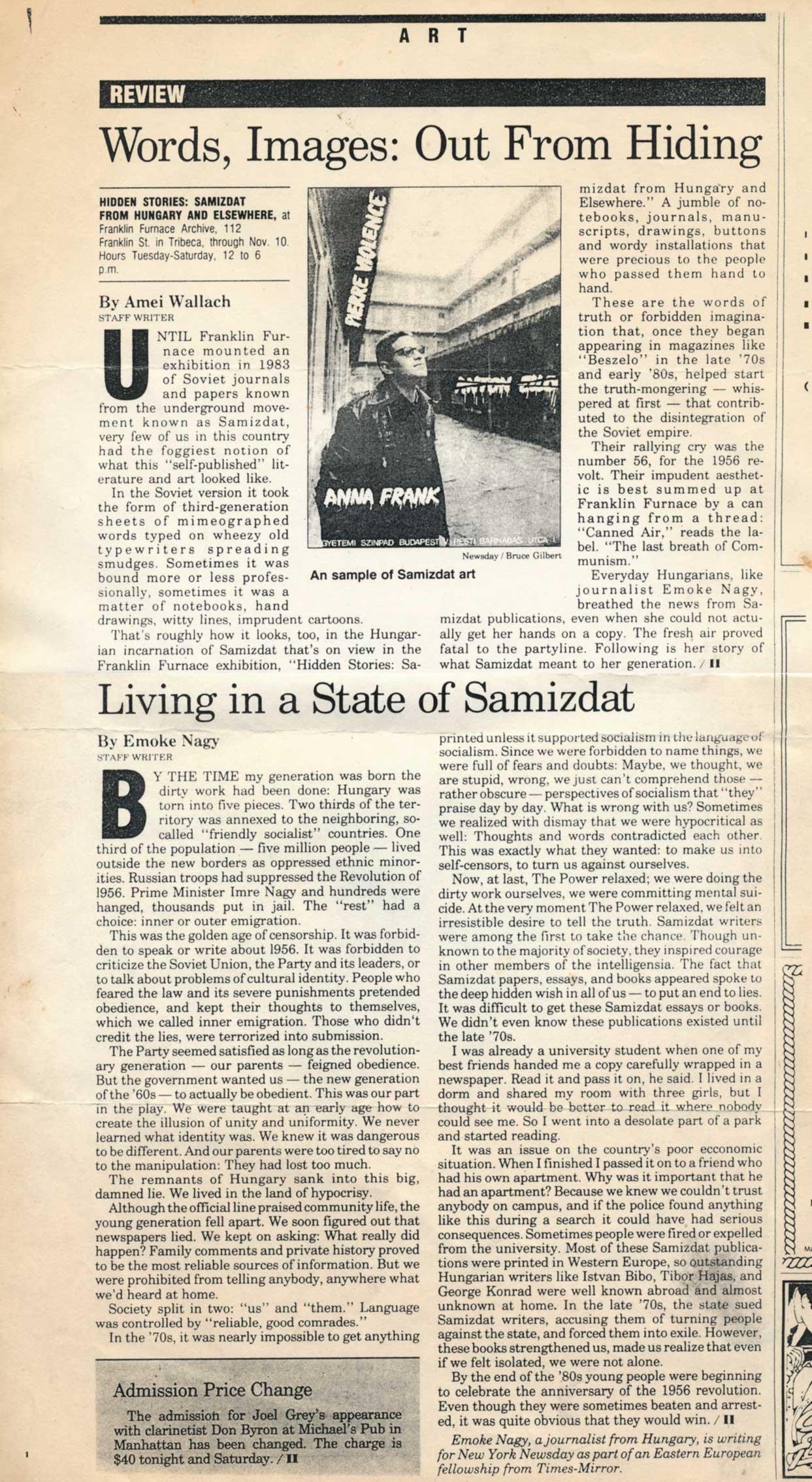

By 1990, as the limits on international cultural exchanges were eased, a number of books of Soviet photography were published in Europe and the US. Virtually all of them, as Jacob showed in his catalog essay for The Missing Picture, adopted the interpretive strategy that he had rejected in his essay for Tibor Hajas: Nightmare Works. Reaching across time to a modernist exemplar, in this case from Alexandr Rodchenko’s photographs “Pioneer Bugler” and “Pioneer Girl,” of 1930, to Antanas Sutkus’s “Pioneer,” of 1964, over thirty years of Soviet photography were relegated to the dustbin of history. “Such histories [are] incapable of accounting for the avant-garde movements that have worked in obscurity in Central Europe and the Soviet Union,” Jacob wrote. “As the Soviet Union has ‘opened’ in the late 1980s, and as samizdat and other alternative histories have been published with increasing regularity, it has become abundantly clear that the Soviet artists who worked during the second half of this century are distinguished by the diversity of their interests and activities.” The Michailov retrospective, covering several decades of his creative activity, offered physical evidence of that diversity. It demolished the Western conceit that art flourishes under democracy.

Jacob mirrored his textual strategy for Nightmare Works in his curatorial strategy for The Missing Picture. In the USSR in particular, conceptual and media-based photography arose within an evolving socialist aesthetics. In critical writing about such photography, therefore, the dialogue with socialist aesthetics, and its link to Socialist Realism, could not be elided except by counter-factual strategies such as the validation by modernist exemplars. As in Hungary, Soviet artists were not immune to historical influence or influence from abroad, but that was not what defined their practices. In his essay for The Missing Picture, Jacob showed the falsity of that interpretive strategy. Then, turning resolutely local as he had with Nightmare Works, he identified Michailov and his circle as influenced by, and following the model of, Moscow Conceptualism. Many among the Moscow School worked with photography in the 1960s and 1970s, when conceptualism and performance were prominent and documentation was a critical concern for artists seeking to preserve records of their activities. The Missing Picture traced a renewed interest in conceptual strategies, historicized by the Michailov retrospective and brought into the present by the group-show of his followers. As he had with Hajas, Jacob again flipped the script, but now in the space of the exhibition itself. Rather than historicize Michailov in relation to the past or the West, the two-part exhibition looked ahead to his influence on the next generation of Soviet photographers.

The exhibition was transformative for Michailov. When Jacob first proposed a retrospective to him, Michailov was shocked. He had his first one-person exhibit outside the USSR in 1989, at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tampere, Finland, with others in planning for 1990 and beyond. He told Jacob he wasn’t sure he could afford to tie up such a large body of work for the anticipated two-year duration of the exhibition tour. Jacob teased him, saying, “Boris, if you do this with me I promise that within two years your work will be exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, and I’ll meet you at your opening.” Michailov laughed, called Jacob a “great bullshitter,” and agreed to Jacob’s proposal. In fact, soon after The Missing Picture opened, Jacob was called by Katy Kline to meet Lynn Cook and Mark Francis, curators of the 1991 Carnegie International, to present Michailov’s work to them. With the validation of a one-person exhibition at the LVAC, in the International, Cook and Francis confidently presented Michalov’s work alongside Richard Avedon, Christian Boltanski, On Kawara, Thomas Struth, and, among others, his old friend Ilya Kabakov. There, too, his work was seen by curators from the Museum of Modern Art. MoMA acquired Michailov’s series By the Ground, and included it in the exhibition New Photography 9, in 1993; not quite two years after the opening at the LVAC. That year Mikhailov’s works were also acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. When, many years later, Jacob and Michailov bumped into each other in Gottingen, while both working on books with Gerhard Steidl, Michailov paid Jacob the compliment of introducing him to Steidl as “my photo grandfather.”

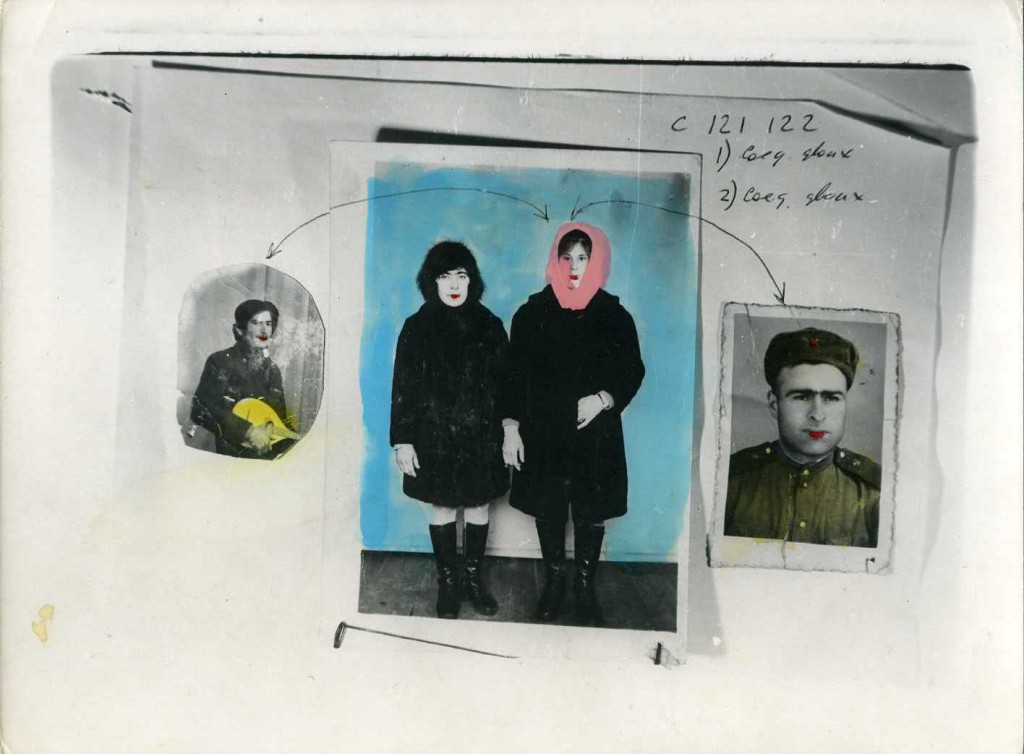

In his text for The Missing Picture, Jacob returned to his formulation of the image as a text under state control, the authoritarian state claiming authorship of all texts. In Eastern Europe, a parallel culture of artists openly produced images belonging to neither official nor unofficial cultures, which Jacob referred to as “unauthorized images” in his essay for Nightmare Works. In the USSR, by contrast, the restrictions on artists, and the punishments for not adhering to them, were both more arbitrary and more severe. Moreover, thaws in the past were always followed by periods of repression, and it was not clear in the late 1980s that this opening of Soviet culture would be different. It was still a dangerous act to make unauthorized images. The category Jacob had formulated for Eastern European photography was thus not applicable to the photographers in The Missing Picture, and he instead defined their work as “oppositional.” Though not inaccurate, this solution was nevertheless not satisfactory for Jacob. It was not their oppositional politics that the exhibition was concerned with, but their oppositional use of the photographic medium. “It is in the work of Boris Michailov that the use of found or acquired imagery becomes a strategic practice in Soviet photography,” Jacob wrote, unveiling it “as a medium that is popularly used to alter reality and to invent… memories.” The photographers’ common tactic of appropriation, in particular the appropriation of Soviet vernacular imagery, worked against the grand narratives of East versus West in politics and of documentary versus subjective in photography. In that respect, Michailov and his circle were both uniquely Soviet and distinctly postmodern in their production. As art historian Tatiana Salzirn wrote of Shulgin’s work, such acts of appropriation function as “commentaries on the genetic code of cultural memory which view every ‘new’ entry in the form of one’s own photographs as a meaningless artistic activity.”

Curator Viktor Misiano observed in 1989, “The only art that can come into being in the Soviet Union today is conceptual art.” All the traditions of Soviet art, bound up in the dialogue with socialist aesthetics and its link to Socialist Realism, were bankrupt; “a narrow collection of visual cliches” in Misiano’s words. International modernism, too, was understood as a dead end. That same year, art historian Margarita Tupitsyn posed the question, “whether alternative Soviet art will finally become integrated into international discourse or be doomed to even further marginalization as an ultimate exotic resort for a libidinal investment of Western orientalist fantasies and desires.” In fact, as Jacob later observed, despite asserting its difference, The Missing Picture was complicit in both sponsoring and documenting the trend toward mass production of conceptual imagery by Soviet photographers, an economically motivated parallel to the production of Sots Art (primarily by Moscow artists) and of Neoexpressionism (primarily by Leningrad artists), for American and German consumers respectively, during the Soviet Union’s unravelling. Purely chronologically, The Missing Picture, as the first to focus on Soviet conceptual photography, helped put that trend in motion. In his text for The Missing Picture, Jacob wrote that “Social documentary photography… when it emerges from second and third world cultures, lends itself to appropriation by Western (first world) institutions.” The same was true of Soviet conceptual photography, which was readily absorbed by the marketplace as a validation and valorization of Western interests. “The idea that the fantasized victory of democracy over Communism should include a reconstruction of the history of Soviet culture according to Western values diminishes Russian artists,” Jacob wrote in 1994, “encouraging the replacement of intimate discourse with mass production of Soviet kitsch for external consumption.” His final essay on Soviet photography sought to make amends with those he had excluded from The Missing Picture, and the consequences of those exclusions.

Later still, Jacob wrote:

It’s difficult to speak of the chaos ensuing from regime change. From my own safe vantage point in the US, suddenly in 1989 there was no iron curtain left to see through. Now every Western eye was trained upon an East that had never existed as brightly in reality as it had in media representations. All those subject to the constraints of socialism, who could never have imagined their annulment by the events of 1989, were at liberty to move and express themselves freely. Some wrote their first resumes and applied for jobs. Others rejected the new economy and lived in poverty. A few took their own lives in despair. Most struggled to adapt and get by. Only a handful made the transition to the international art market. Even for them, however, the attention from abroad faded just as suddenly as it had appeared.

Boris Michalov was the exception. Western attention to his work never faded, and he has resolutely defied “marginalization as an ultimate exotic resort for a libidinal investment of Western orientalist fantasies and desires.” As Jacob wrote for The Missing Picture, “Michailov’s [photographs] are, without exception, confrontational.” He remains obdurately true to his origins as a photographer.

The Missing Picture: Alternative Contemporary Photography from the Soviet Union (Open/Download PDF)

December 8, 1990 – February 3, 1991

List Visual Arts Center at MIT, Cambridge, MA

Contributors:

Boris Michailov (solo exhibition)

Vladimir Kupreanov, Ilya Piganov, Maria Serebrjakova, and Alexey Shulgin (group exhibition)

Texts: Katy Kline, Tatiana Salzirn, and JP Jacob

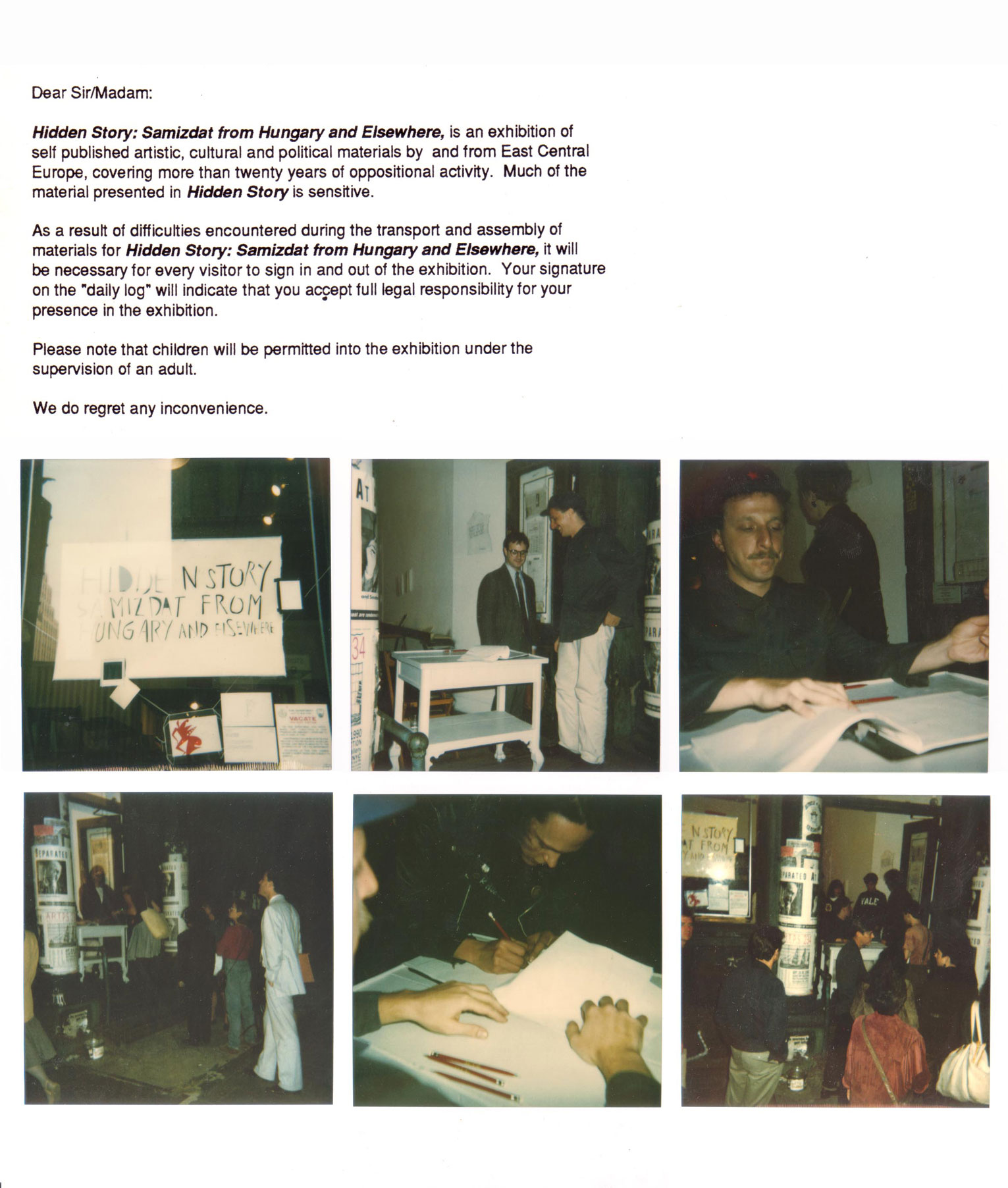

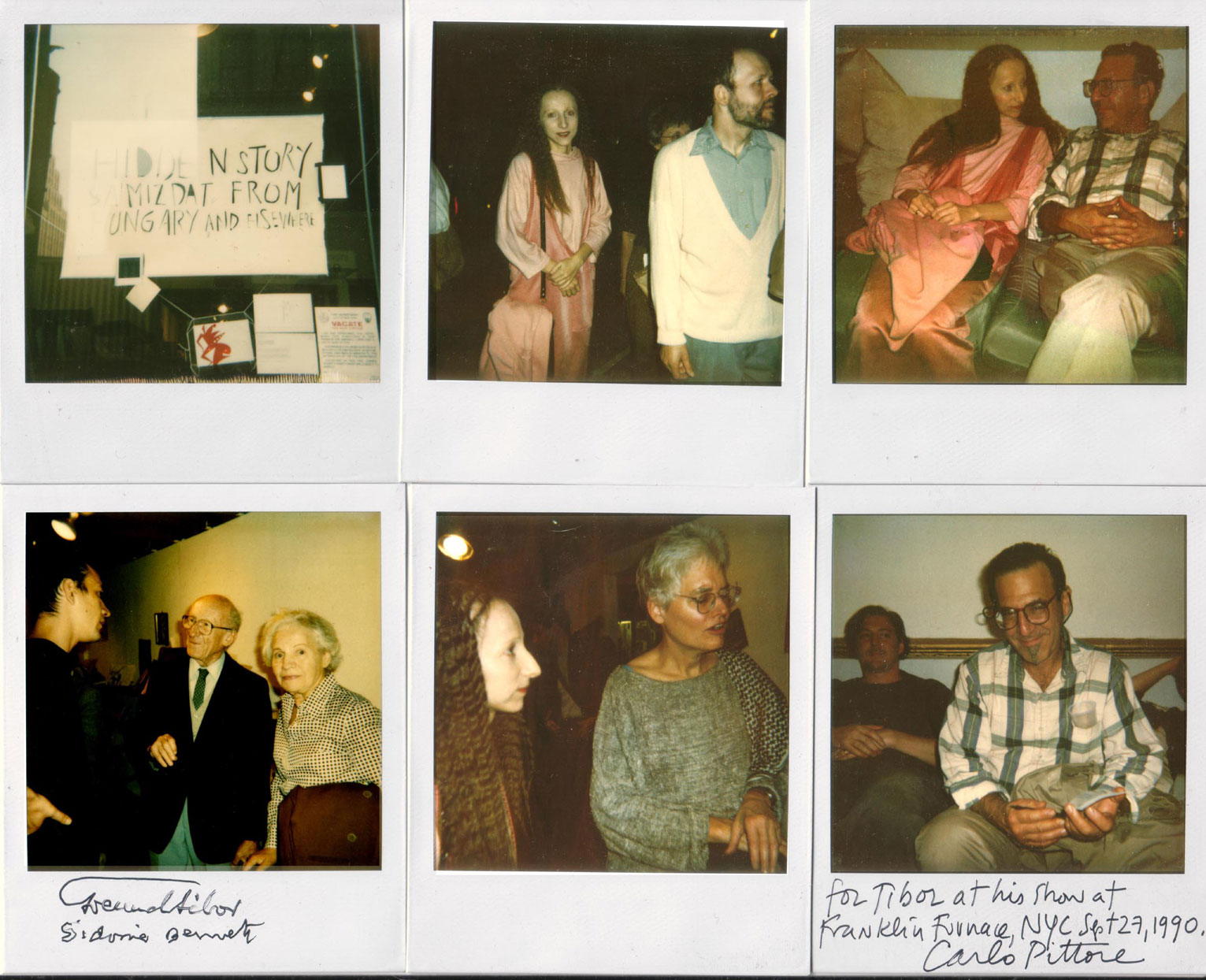

Hidden Story: Samizdat from Hungary and Elsewhere

In his text for The Missing Picture, Jacob wrote of the avant-garde movements that worked in obscurity in Central Europe and the USSR. “As the Soviet Union has ‘opened’ in the late 1980s,” he noted, “and as samizdat and other alternative histories have been published with increasing regularity, it has become abundantly clear that the Soviet artists who worked during the second half of [the twentieth] century are distinguished by the diversity of their interests and activities.” As The Missing Picture offered evidence of that diversity in Soviet art, so Hidden Story: Samizdat from Hungary and Elsewhere offered evidence for it in Eastern European art. Together, the two exhibitions demolished the Western conceit that art flourishes under democracy.

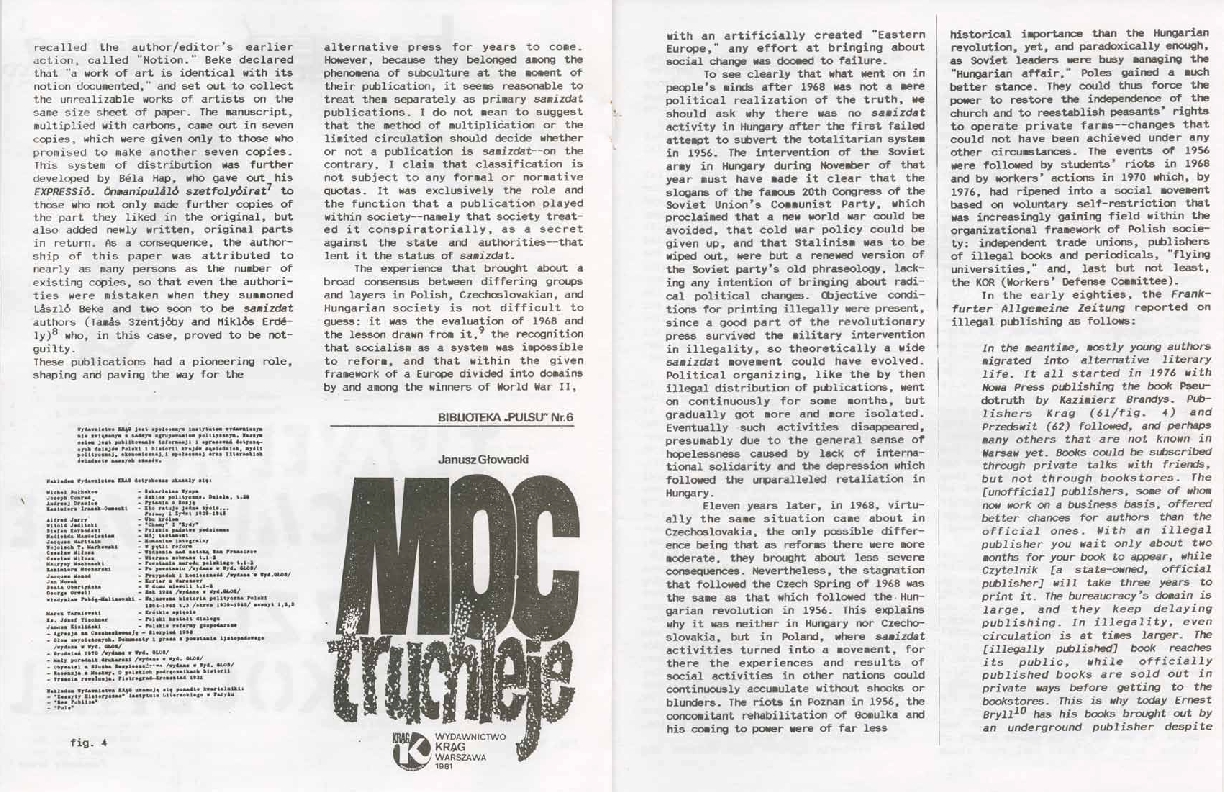

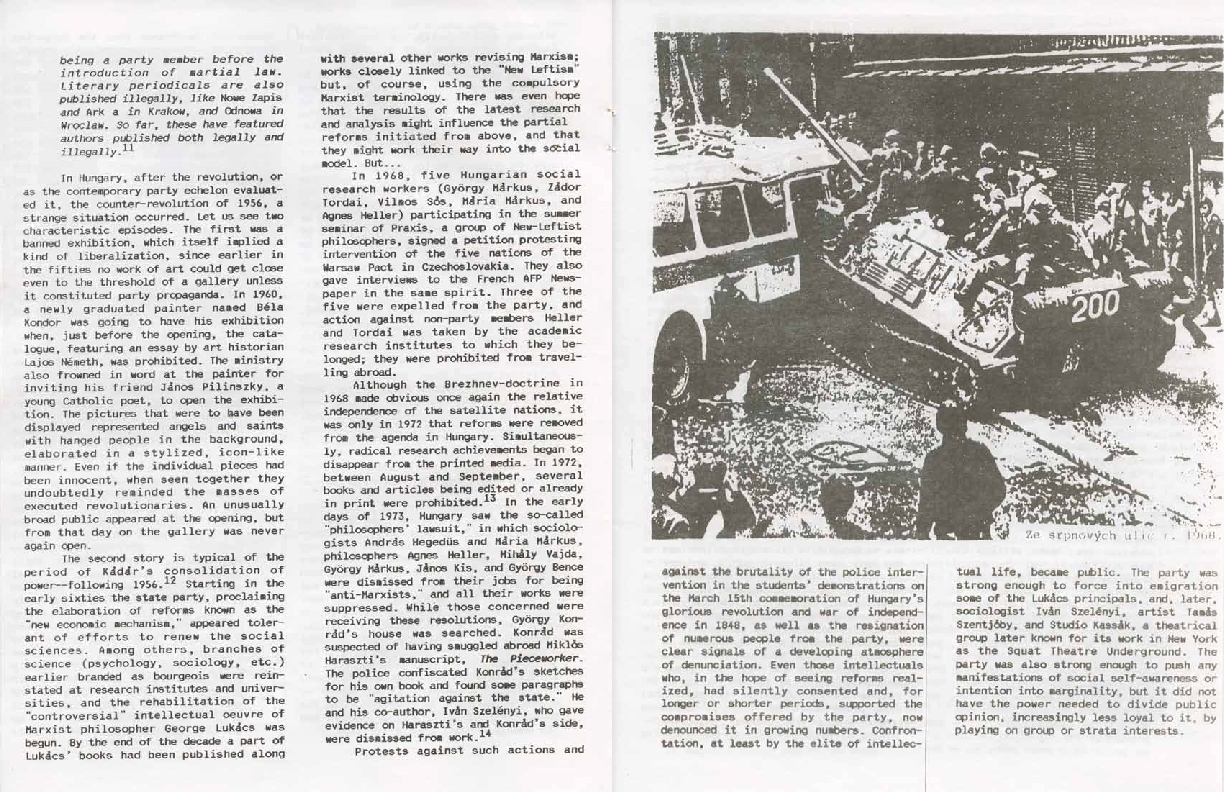

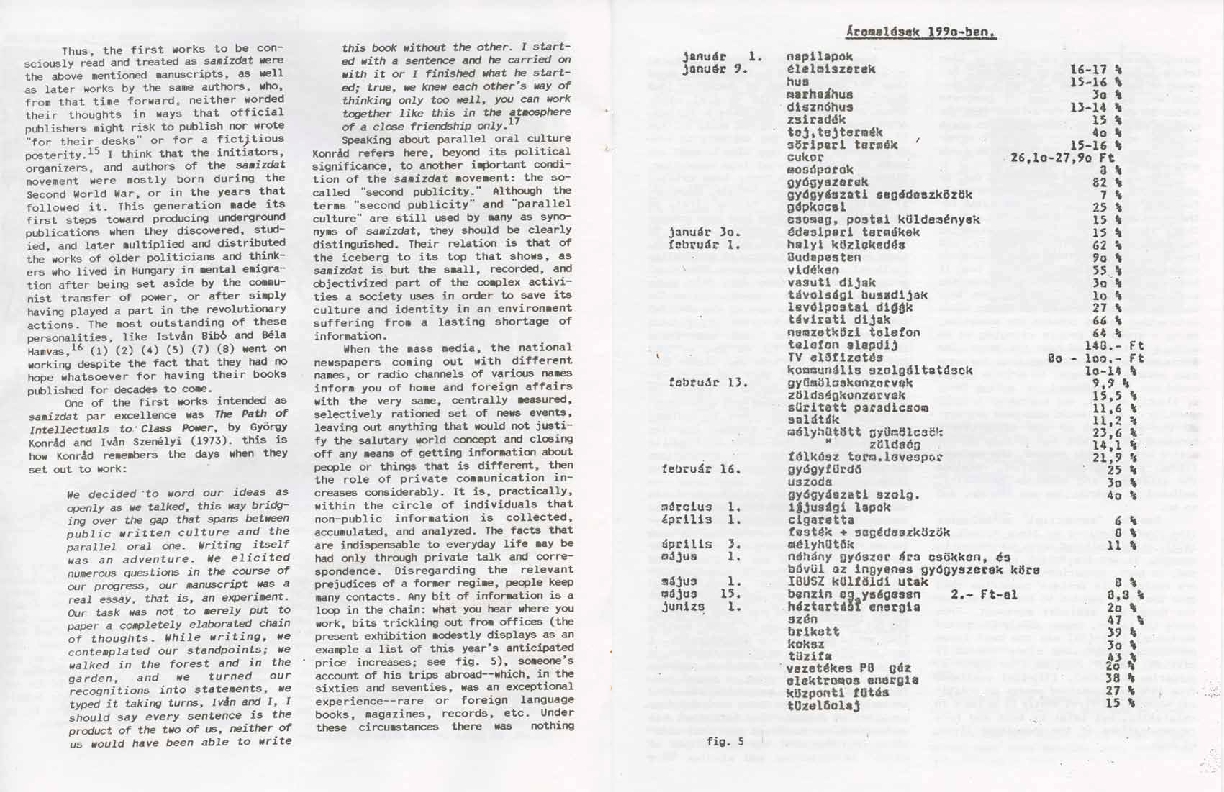

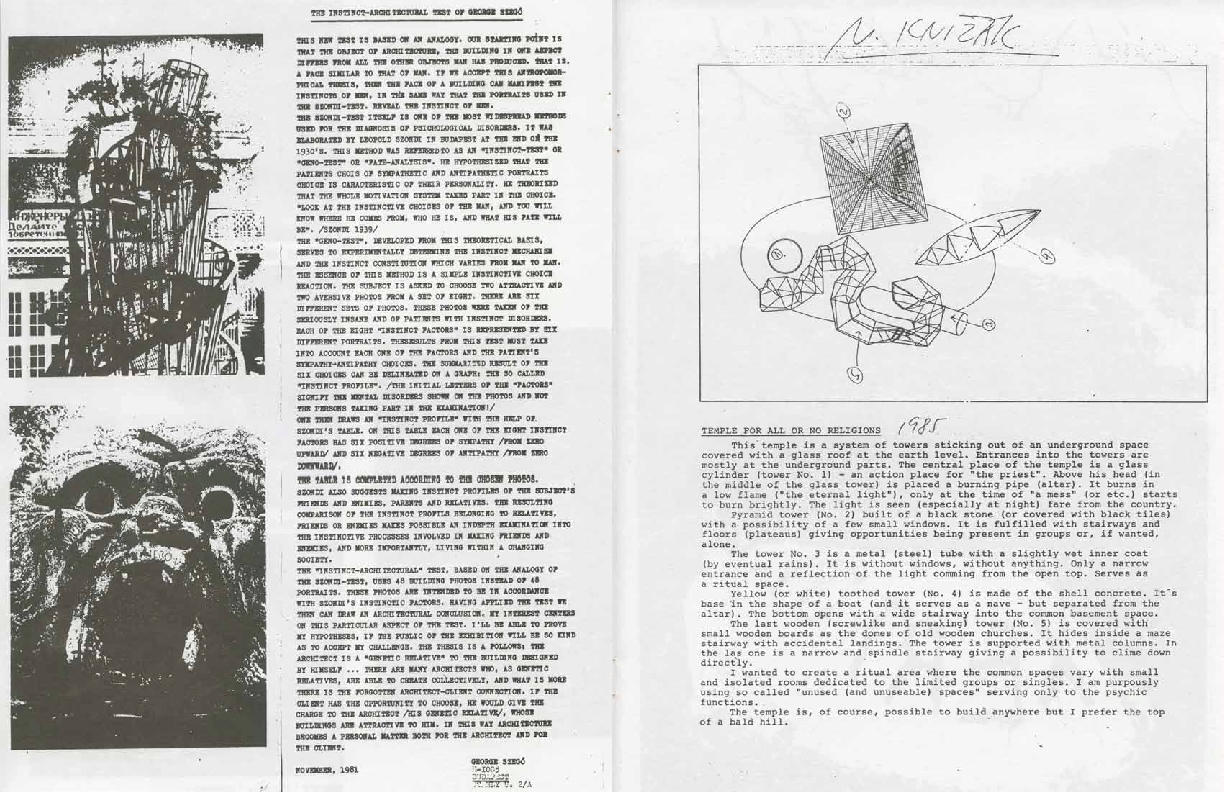

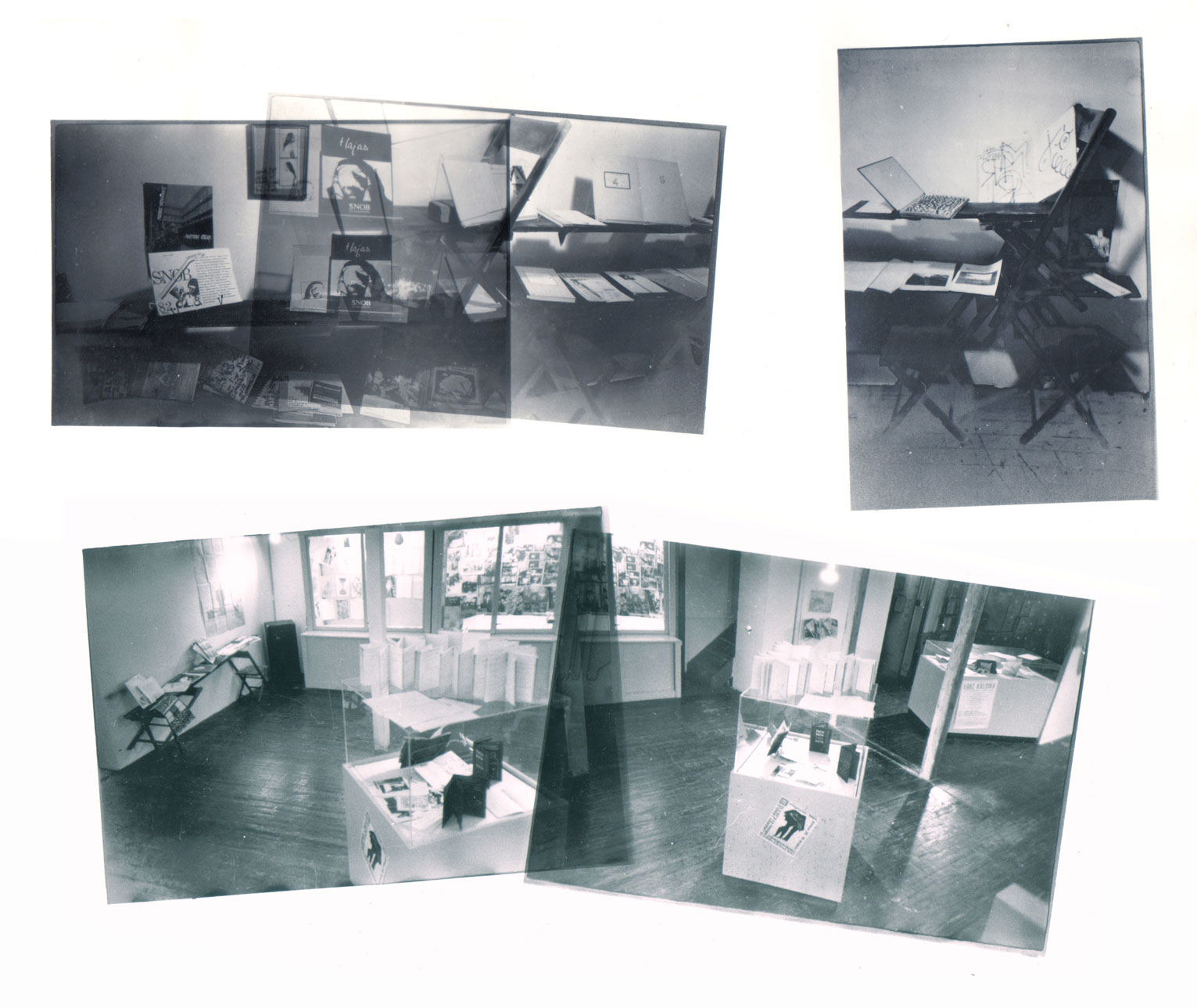

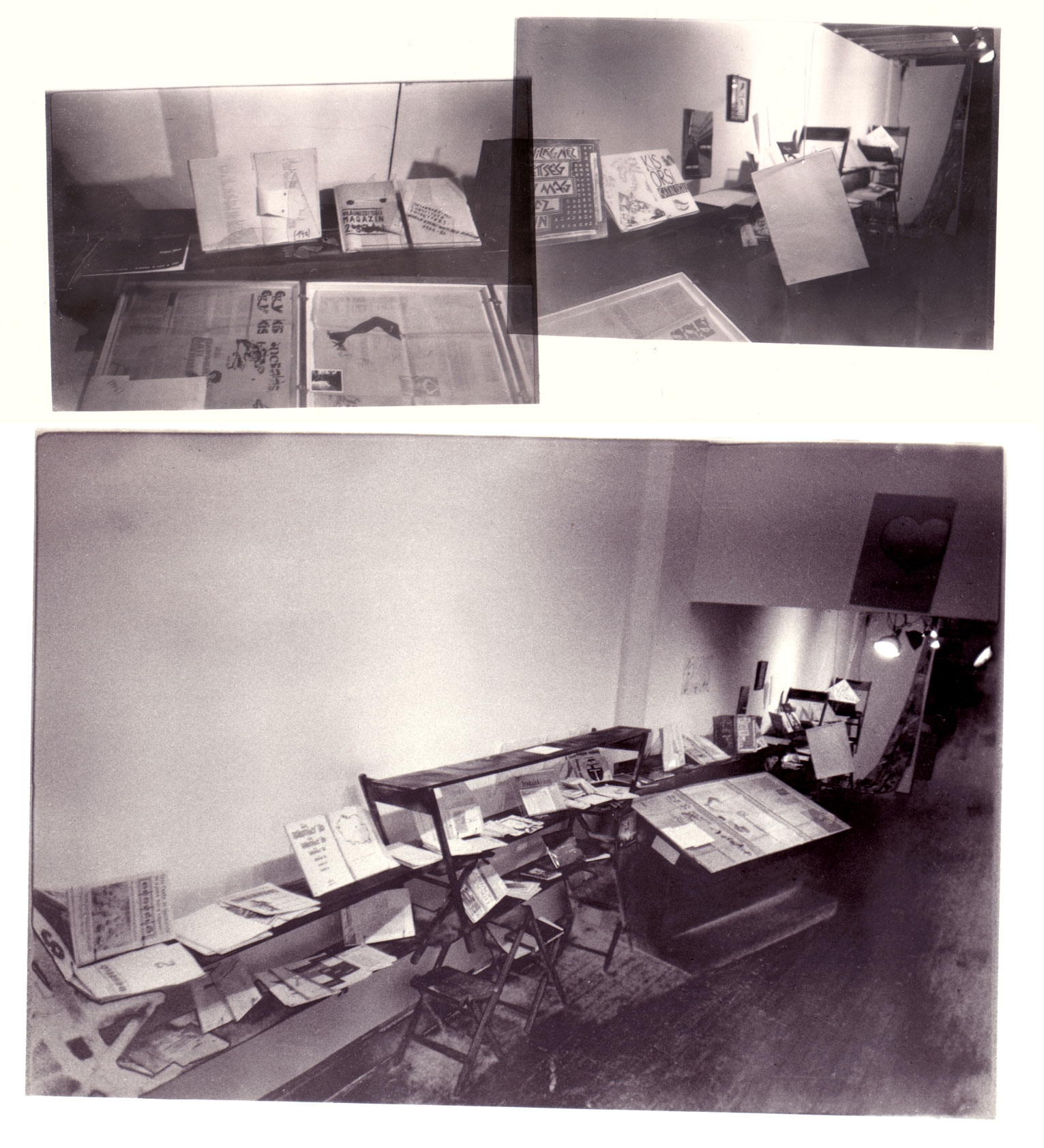

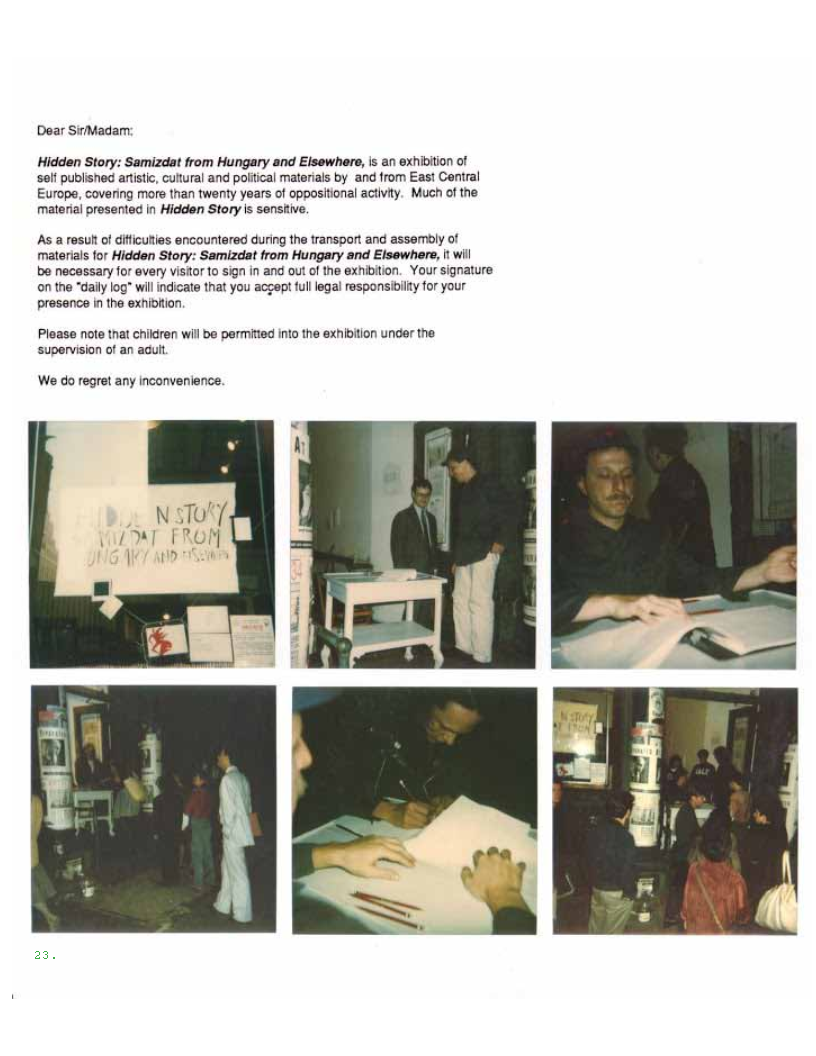

Hidden Story presented three hundred twenty objects from Hungary, Poland, and Czechoslovakia, dating from 1956 – 1990. Since the selection was not confined to political publications in the literal sense, it presented remarkably rich material with a view to artistic forms: self-publishing, political, cultural and art books, book series, zines and magazines, (AL, AB HIRMONDO, BESZÉLŐ, Cseresorozat, TANGO, Világnézettségi Magazin etc., and publishers: ABC, ARTPOOL, HITEL Független Kiadó, KRAG, M.O, SzNOB International, SNTL, WSH etc.) and a number of cassettes, stickers, posters, pins, badges, T-shirts, arm-badges, documentation of various illegal street actions, etc. Émigré writer Emoke Nagy, in his review for New York Newsday, described the exhibition as representing “the golden age of censorship.”

Jacob later wrote:

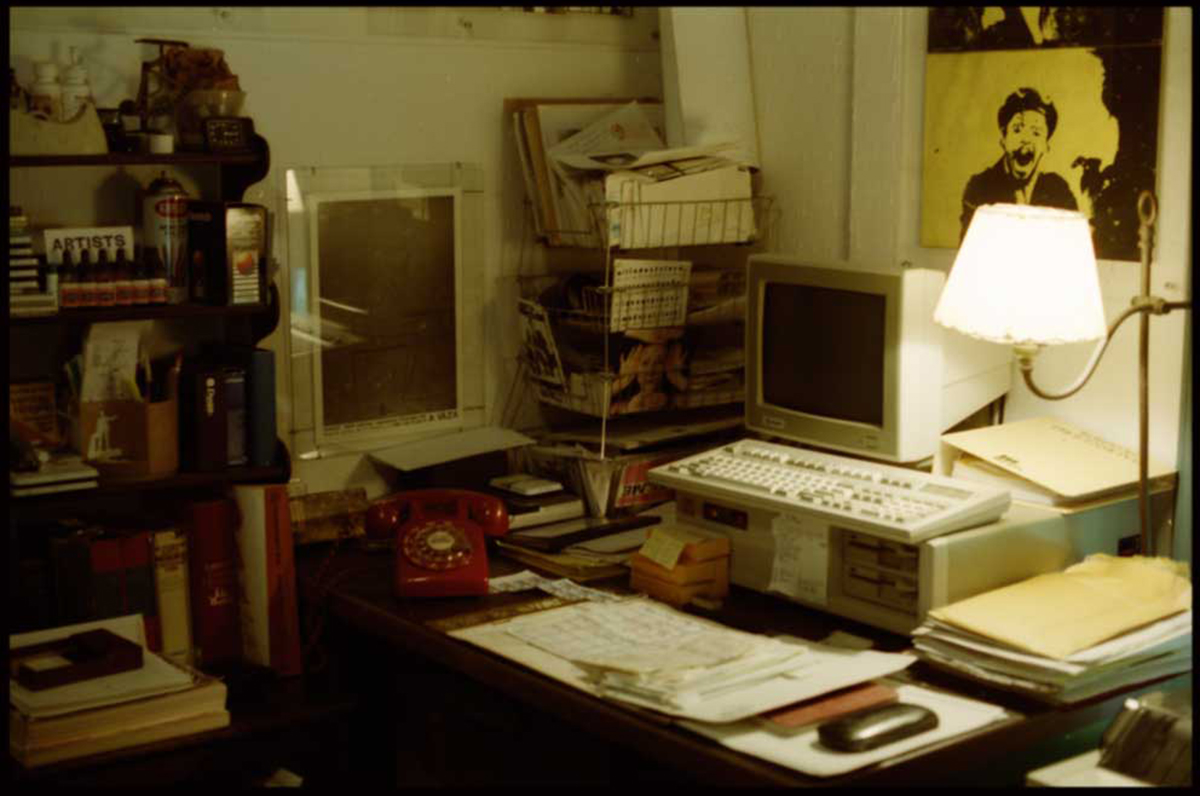

Even before my first visit to Hungary, Tibor and others in Budapest had arranged to have a remarkable assortment of publications couriered to me in New York, including the Helyettes Szomjazók Világnézettségi Magazinja and the first Liget Galéria Almanach, as well as works by Xertox, Group Inconnu, and Artpool. These publications, which I received at the same time that I was reading historical evaluations of post-war Hungary, presented me with the paradox of a culture with multiple histories, each equally distinct. The dimensions of that paradox became clear when I visited Budapest for the first time in 1986, and met with Péter Bokros, Gábor Tóth, György and Julia Galántai, László Fe Lugossy and others. During my second trip to Budapest, and throughout the next few years as our conversations about a samizdat exhibition evolved, Tibor introduced me to increasingly complex visual and textual materials, including the artwork of Tibor Hajas and Miklós Erdély, and the articles of László Beke and Miklós Peternák.

Hidden Story was scheduled to open in September 1990, at the Franklin Furnace, a perfect venue. A former industrial loft re-built by artists, the Furnace began as an exhibition space for artists’ books and periodicals, and later expanded to include all forms of text-based art, including graffitti, performance, mail art, and other more or less ephemeral activities. It was important to me, too, that Rimma Gerlovina’s and Valeriy Gerlovin’s Russian Samizdat Art, the only other exhibition of privately produced art and text, was presented at the Furnace in 1982. It was founded and directed by Martha Wilson, a performance artist who at one time changed her name to Nancy Reagan. Utterly informal, Martha acknowledged the importance of our exhibition by handing me a check and a key to the gallery door. I imagined that Tibor would feel at home.

Hidden Story was, for me, an exhibition with great personal significance. I began to correspond with artists in Eastern Europe because I was interested in the idea of communication; over what distances and barriers might one successfully communicate with others? The peculiar objects that had brought me into contact with the densitiy of Hungarian history and culture began, in my mind, to replace the dictionaries that Tibor and I stacked between ourselves so that our conversations need never be halted for want of a word. Gradually, I came to see the exhibition as an outgrowth of those conversations, a way to share with others the lessons that I had learned in Budapest and elsewhere in Central and Eastern Europe. But by 1990, the world had changed. The Warsaw Pact had collapsed. Perhaps it was already too late for such an exhibition?26JP Jacob: Closing the Book: Samizdat in New York City, nd

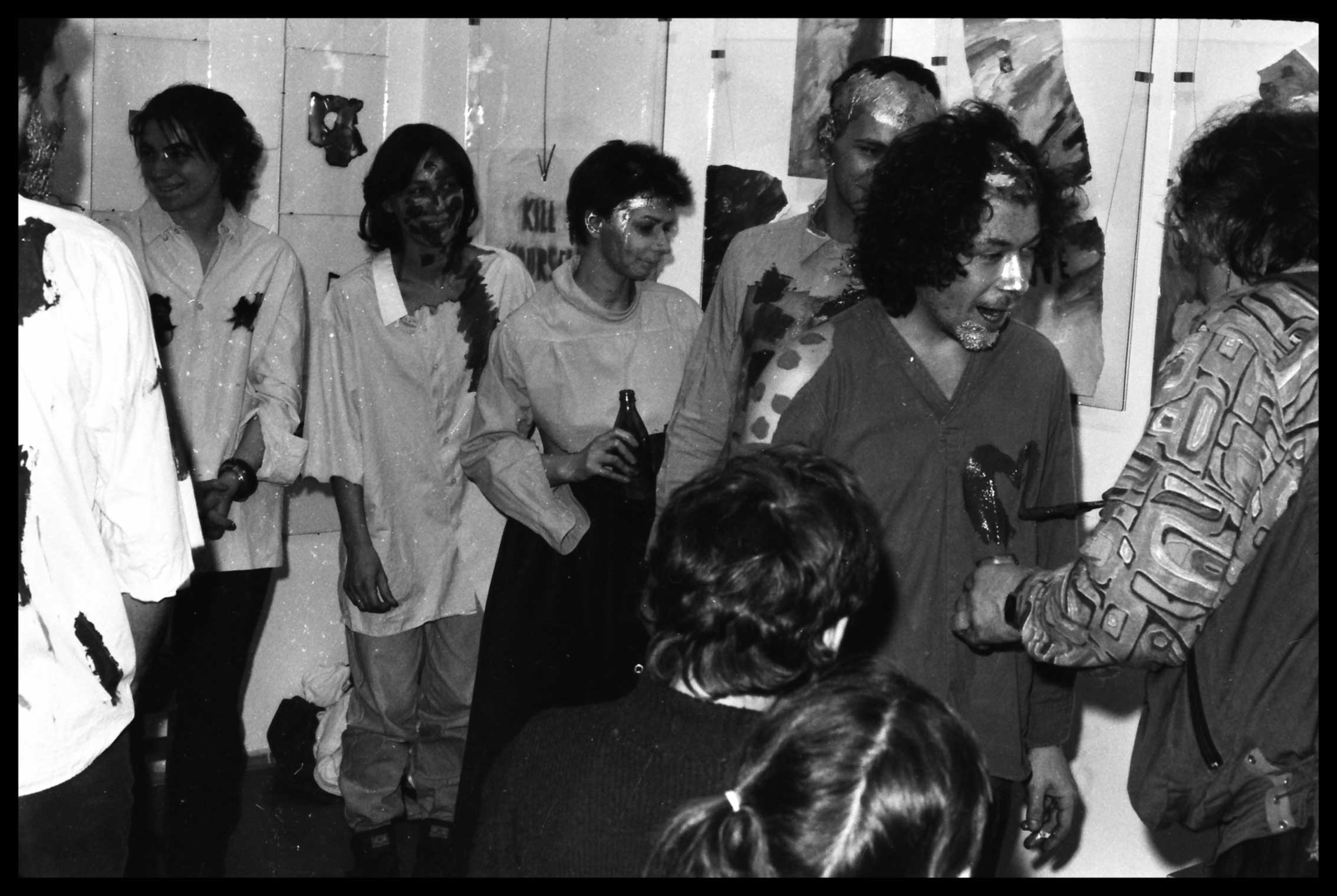

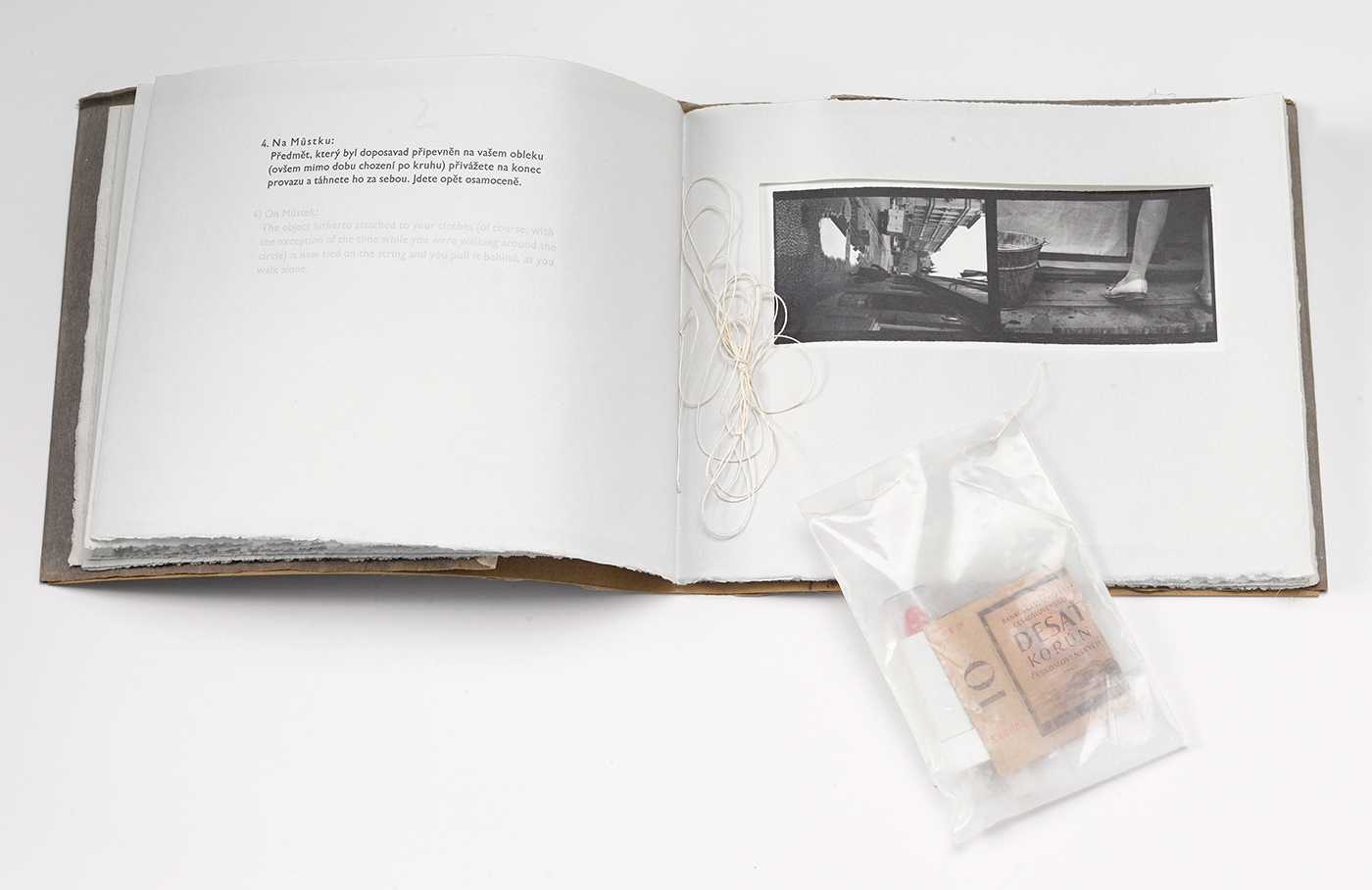

Tibor and Andi Várnagy flew to Bloomington, Indiana, where Jacob was newly enrolled at Indiana University. The entire exhibition was couriered in an enormous red suitcase. Jacob had rented two Canon copiers with which they designed and printed the exhibition catalog and related printed matter, copying directly from the checklist objects. They conceived a kind of performance to be carried out at the opening, arranged for the Furnace to purchase brown paper bags for the catalogs to be packed in, then Várnagy traveled on to New York City.

Várnagy insisted that, with a few exceptions, the objects should be displayed openly so that viewers could pick them up and examine them closely. The shelves on which they were displayed were made from old wood found in the basement of the Furnace and on the street, all held in place by pyramids of folding wooden chairs.

At the opening, a table was placed in the doorway of the Furnace so that only one person at the time could enter. During the opening, one of the Furnace’s staff, named Harley, sat behind the table, performing the role of a guard in a khaki suit and a cap with red star (a souvenir from China). Harley refused to allow visitors into the gallery until they signed a form which demanded such personal information as date of birth, residence, mother’s maiden name, etc.

Visitors to the exhibition had the choice of providing the factual information to the guard at the entrance, providing him with false information, pushing past the guard without providing any information at all, or refusing to enter the exhibition. Each choice carried implications: complicity, resistance, refutation. For the most part, viewers regarded the performance as a game. Most willingly gave the information required and headed for the refreshments.

During the opening Jacob was called out to the street three times to speak with people angered by the guard at the door. Each of the three was an immigrant, and each declared that the reason they had chosen the US to live in was its freedom from such random exercises of authoritarian power. They were the only visitors to the exhibition who failed to recognize the event as a performance. Only one visitor was so angered by the performance that she pushed past the guard, refusing to provide the personal information required. As she pushed her way into the gallery she ran into the first of Várnagy’s rickety shelves. The shelves collapsed, and books flew across the floor. “You’re the only visitor tonight who has refused to be intimidated,” Jacob told her. “I hope you understand where your action places you in relation to those who produced the objects we’re exhibiting.”

Hidden Story: Samizdat from Hungary and Elsewhere (Open/Download PDF)

September 27 – November 10, 1990

Franklin Furnace, New York, NY

FF Catalog Description:

Handbook by Tibor Várnagy and John P. Jacob, curators of the exhibition, which amassed publications gathered illegally from Hungary and other countries in Eastern Europe. Hidden Story doubles as an exhibition catalogue and an example of Samizdat. Includes detailed descriptions of each work, a complete checklist, and art texts and essays by George Szego, Simon Csorba, Zsolt Kishonthy, G.A., Gergely Molnar, Marek Janiak and Andzej Kwietniewski, Hejettes Szomjazok, John P. Jacob, Tibor Hajas, Bela Hamvas, Janos Kis, and Tibor Várnagy. Visual works by Levay Jeno, Regos Imre, Robert Swierkiewicz (Xertox), and others.

Binding, Editions, Size:

82 pages, saddle-stapled, 52 black-and-white illustrations, 8×11” in brown paper bag, with handcut rubber-stamping

Liget Gallery page:

http://www.ligetgaleria.c3.hu/111+1+1.htm

Related: Installation photos from Promote, Tolerate, Ban: Art and Culture in Cold War Hungary, Getty Research Institute and Wende Museum, 2018

Related: Isotta Poggi, The Photographic Memory and Impact of the Hungarian 1956 Uprising during the Cold War Era, Getty Research Journal, Number 7, 2015, pp. 197-206

Out of Control: Photography from East Germany

Foreword

Karla Sachse, Berlin, April 1993

At first glance, the following texts differ too widely to give us coherent information about the past existence of art photography in the German Democratic Republic. However, it seems no coincidence that out of all the different possible and considered perspectives these three come together at this time and under these circumstances.

In the past years Wolfgang Kil has attempted several times to get an overview of and to penetrate analytically the connections between developments in the social reality (and surreality) of the GDR and photography. It may be for this reason that he accepts the desire to strike a balance once more unreluctantly, even though he is one of only a few people who have long placed the specific internal developments in an international context – modern as well as post-modern. And he less than ever hides the fact that, in doing this, he proceeds from a position for which a certain moral claim and human interest remain important. Kil has returned to his original field of activity – architecture – which was closed to him during the existence of the GDR. And even though this for now latest text about photography was written for a specific group of photographers it nevertheless depicts a background for very diverse forms of artistic articulation. By striking a general balance he also avoids name-dropping which a number of art dealers seemingly use only to gauge the usefulness of single photographers for the western art market or to use entire branches of artistic evolution to “prove” trends in East German photography or “astonishing” parallels with Western conceptions [of art].If a few photos in that text are classified (not by Kil himself, by the way) then they, too, are abused as pieces of evidence. Accordingly, they should be viewed with caution – and above all they should make you curious.